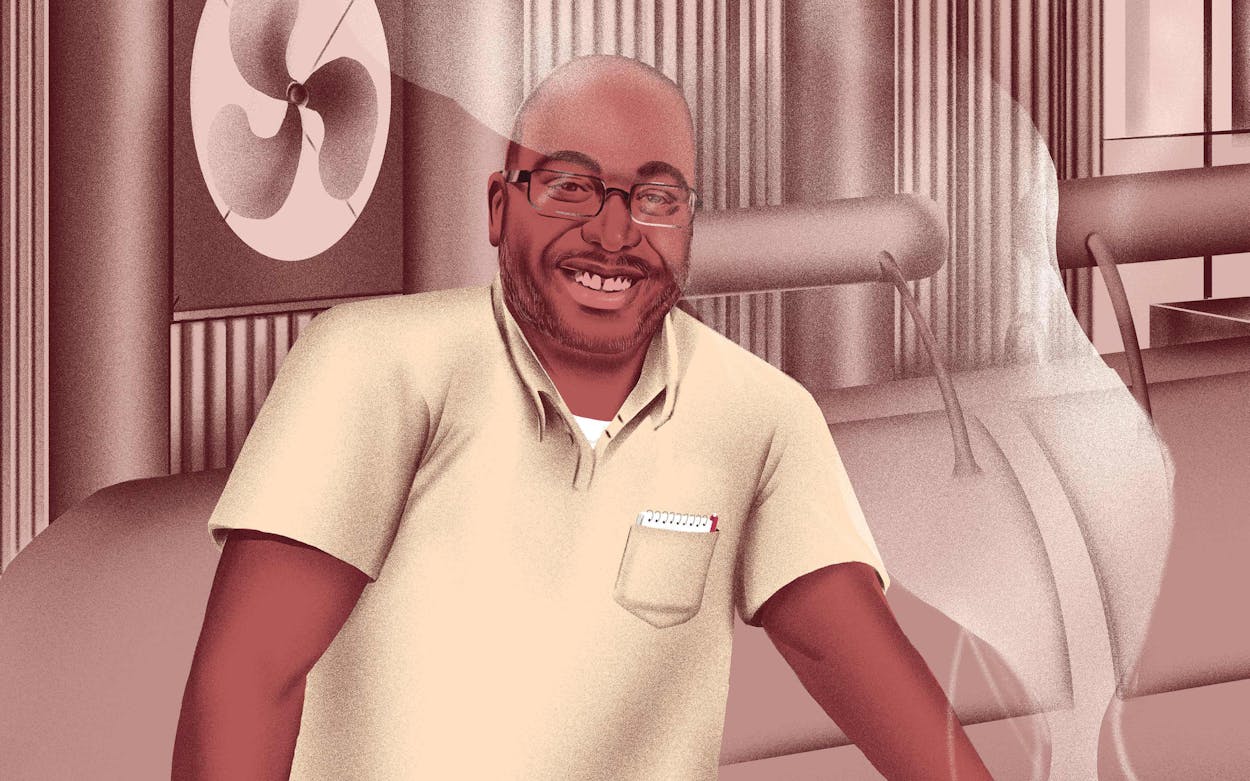

Colorado native Adrian Miller lives in Denver—not exactly a barbecue capital—but the lawyer turned food historian has been passionate about smoked meat ever since he went on a tour of legendary Central Texas joints in 2002. Miller, who served as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton before leaving that world to focus on foodways, won a James Beard Award for his first book, 2013’s Soul Food: The Surprising Story of American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. During an extended, self-guided study of U.S. barbecue that brought him back to Texas (where he checked out places such as 109-year-old Patillo’s BBQ, in Beaumont), Miller found the written history to be light on the contributions of Black pitmasters. He hopes to set the record straight in Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue (University of North Carolina Press), which comes out April 27. Here, he shares a few things he learned.

On barbecue styles.

Around the country, Texas barbecue is the dominant aesthetic right now. Even in Denver, what is presented is always the Central Texas type: the sliced brisket—beautifully manicured, Instagrammable. I wish people would explore South Texas and especially East Texas more. I like the fact that the Black barbecue I’ve eaten in East Texas is kind of messy.

Sauce or no sauce?

Sauce is huge in Black barbecue. I talked to a lot of African Americans who said, “Anybody can cook the meat; the sauce is really what’s key.” Old advertisements and articles show that the marquee item at many of these historic Black-owned barbecue joints was the sauce.

Menu mainstays.

Almost everywhere I went, there were spareribs on the menu—we like that rib tip attached. Brisket is not as important. If there’s a holy trinity of Black barbecue, it’s this: spareribs, hot links, and chicken. I saw a lot of peach cobbler and banana pudding. Potato salad and beans are the most consistent sides, but in the Midwest it’s fries.

A favorite figure.

One character I loved was Marie Jean [a.k.a. Mary John] from Arkansas, an enslaved woman in the 1840s. Today we would call her a pitmaster. To come across a story about a Black woman at that time who was in charge of barbecue, basically telling dudes what to do, was just incredible to me. She bought her freedom and ran a restaurant that was highly regarded in Arkansas Post, Arkansas. When she died, the white newspaper eulogized her, with a side of racism for sure, but for this woman to get this praise, I just thought she was a fascinating figure.

Changing attitudes.

I was not exposed to white barbecue growing up. I ate barbecue at home, so I used to have a narrow definition of barbecue. If a Black person wasn’t cooking it, it was highly suspect. Now that I’ve looked at barbecue traditions around the world, I have a much more expansive view, which is a curse because now trying to define barbecue is like trying to catch a greased pig.

This article originally appeared in the April 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Hidden History of Black Pitmasters.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Books