I have a Twitter follower who, for a while, enjoyed pointing out when a barbecue joint spelled their name “incorrectly.” Presumably, “Barbecue” and “BBQ” were acceptable, but not “Barbeque,” “Bar-B-Q,” or its slight variation “Bar-B-Que.” He’s not alone. The AP Stylebook, generally used by journalists, doesn’t like those alternate spellings either, as they tweeted last year:

AP Style tip: barbecue is cooking foods over flame or hot coals. Noun refers to both meat cooked and fire pit. Not barbeque, Bar-B-Q or BBQ.

— AP Stylebook (@APStylebook) May 15, 2015

When I record the name of a barbecue joint on TMBBQ, I’m careful to check their sign or their website for the spelling they prefer. (Sometimes even their own signage differs, to my consternation.) But I decided to look back at the names I’ve featured so far on this site to get some idea about the popularity of each derivation of “barbecue” when it comes time to name a barbecue joint.

“Bar-B-Q” and “Bar-B-Que” are by far the favorites, at 200 combined. Placing second is “BBQ” with 121 restaurants preferring this variation, and far back in third and fourth are “Barbecue”(44) and “Barbeque” (34).

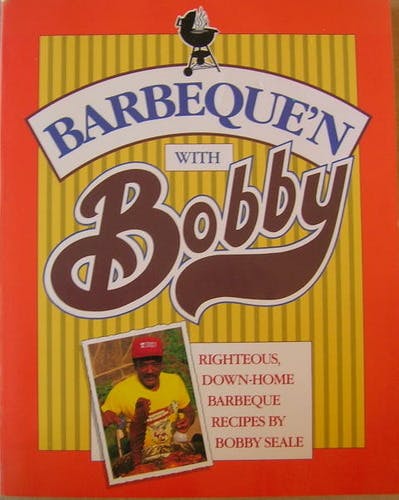

Those results wouldn’t surprise Bobby Seale. More famous for his role in founding the Black Panther Party, the native Texan also authored a cookbook, Barbecue’n with Bobby. He describes the cooking methods of his uncle, who owned Tom Turner’s Bar-B-Que Pit in Liberty, Texas. The key to cooking the ribs was to baste them while they sizzled over hickory wood, but the name is what helped get people in the door, according to Seale. “I had very seldom seen a pit or restaurant sign that used the dictionary spelling barbecue (especially in the Black community),” he wrote, explaining that “Bar-B-Que” and “BBQ” were coded to mean real barbecue. “I began to feel that the ‘cue’ spelling represented something drab, or even square,” he continued, suggesting that “barbecue” was meant for whites, and likely wasn’t cooked with wood.

In the new book Virginia Barbecue: A History, author Joseph R. Haynes found just the opposite in post-WWII Georgia. He studies various uses of “barbecue” and its iterations, and tells of a group in Atlanta who specifically boycotted restaurants using the name Bar-B-Q on their signs. In their words, “such a sign means the place is offering nothing more than underdone pork roast slathered in an unpleasant-tasting hot and bitter sauce.” In a thorough dive down the rabbit-hole of barbecue etymology, Haynes traced the first usage of many barbecue variations, including “barbeque” which was first printed in 1744 while “Bar-B-Q” doesn’t come into common use until the turn of the twentieth century. As we’ve explored before, “BBQ” came along as a further shortening in the thirties.

I looked back at old newspaper records to see if I could find a pattern of usage for the terms, but it was a thoroughly mixed bag. Barbecue and barbeque were both used to describe public events where large quantities of meat were cooked. In Omaha, Cincinnati, and even Los Angeles, “barbeques” were popular before the turn of the century. In 1883, the Dakotaian wrote about festivities planned around the cornerstone setting ceremony in Bismarck, then the capital of the Dakota Territory. “It is also preposed [sic] that an ox be roasted and a barbeque be prepared for the country people who are expected to be present in thousands,” the paper wrote.

The first mention of “barbeque” in relation to a restaurant was a 1917 ad for El Paso Barbeque in the El Paso Morning Times. It was ironically listed under the “Barbecued Meats” section of the classified ads. Several more ads from the twenties and thirties in the Texas Panhandle hawk “Hot Barbeque” in Borger, Crosbyton, and Shamrock. The ad at the top is for Borger’s Barbeque Inn where you could find “Real Barbecue” in 1927. The combination of two spellings is repeated in 1934, where “Hot Barbecue” could be found in Rockdale’s New Barbeque Stand in 1934.

Through the twenties and thirties, with more barbecue joints going to neon signs, “Bar-B-Q” and “BBQ” began to replace longer words like “barbecue” and “barbeque.” As discussed earlier, those neon-friendly designations are still popular today, for both black-owned and white-owned joints. I still wondered if Seale had a point about “-cue” being code for a white-owned establishment. I looked back at The Negro Motorist Green Books published between 1936 and 1966 for some insight. They were business directories published by Victor H. Green to guide African-American travelers to hotels, auto shops, and restaurants known to be friendly. In the final issue I counted 21 barbecue joints listed across the country and not a single one had a name that ended in “-cue.” I’d like to think that Beaumont Barbeque in Dallas and Long’s Bar-B-Q in Beaumont, the only listings in Texas, weren’t serving any drab barbecue.

- More About:

- Black BBQ