At the meat markets of yesteryear, a boneless brisket would have been a special order. If beef was arriving as a half carcass, there would be no need for the butcher to remove the bones before selling or smoking the cut; doing so would have meant more work for less money.

The brisket we buy from supermarkets today—packed tightly, without bones, in a plastic sheath—is a derivative of the old meat market cuts. And, funny enough, finding a bone-in brisket is nearly impossible today. A special order from a butcher isn’t out of the question, but you’ll have no luck at any major grocery store. I’ve never found a barbecue joint that still cooks the cut (despite what one Wall Street Journal reviewer would have you believe about Franklin Barbecue). The cryovaced, boneless brisket—IMPS 120 as opposed to the bone-in IMPS 118—is so commonplace, that it surprises some barbecue lovers to learn that a brisket ever had bones attached to it.

A century ago, the term “brisket” meant that it had bones; a boneless version was typically called a “rolled roast.” As a Fort Worth Star-Telegram article from 1914 called “Divisions of Beef that Housewife Should Know” explained, “The ends of five ribs are included in the brisket. The ribs are taken out, the meat is sold as rolled roast, or corned and sold as boneless brisket.” Only if it became corned beef did it keep the name brisket.

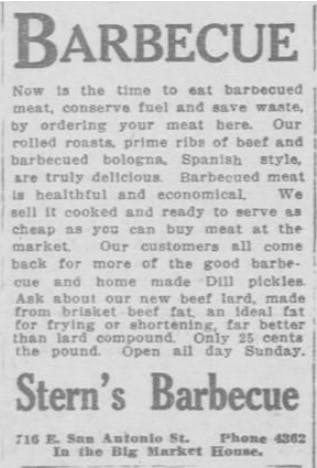

In El Paso, an 1918 ad for Stern’s Barbecue mentioned their “rolled roasts, prime ribs of beef and barbecued bologna.” Brisket isn’t mentioned by name, but that might be what the rolled roast referred to.

As we’ve noted previously, Texas meat markets didn’t discriminate when it came to the beef cuts that made it into the smoker. Brisket was certainly in the mix, like any other cut of beef that customers weren’t buying raw, but it wasn’t revered as a singular barbecue cut in Texas. That is, until the sixties when boxed beef came onto the market.

Prause Meat Market in LaGrange has been operating since the 1890s, and they’ve been serving barbecue for almost as long. “In the late seventies, the bone-in brisket left and the boneless brisket started,” Gary Prause, the current owner, said about meat in their case. “It got down to where the last fifteen or twenty years, it’s been straight boneless brisket.” He didn’t remember the last time he had a bone-in brisket in the case.

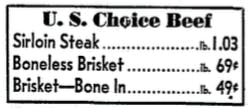

We can begin to see the shift from bone-in briskets to boneless ones just by following the advertisements for boneless briskets. When the bone-in version was still dominant, grocery stores and meat markets had to specify when they were selling a boneless one, a designation which also clarified the higher price. An early boneless brisket ad from Wyatt Food Stores appeared in a 1934 issue of the Dallas Morning News. Boneless brisket was $0.13 per pound and bone-in beef brisket was “A Real Bargain” at $0.09 per pound. In the fifties, more ads began to appear for boneless brisket, like the one above from A&P.

As time wore on, boneless brisket became commonplace, negating the need for the “boneless” designation. However, I was surprised to see boneless brisket make an appearance in the movie Slacker. Filmed on location in Austin in 1989 (the film was released in 1991), a scene near the 57-minute mark takes place outside of a supermarket. Above the actors portraying a shoplifter and a security guard is a flyer for “Cry-O-Vac Boneless Heavy Beef Briskets.” Ads like that now come along as often as briskets selling for less than a buck per pound.

One major reason for the disappearance of the bone-in brisket is that cryovac packaging. The technology was revolutionary in the seventies, but bones were an enemy of the thin plastic bags. Bone guards were developed for cuts like ribs, where removing the bones was all but impossible, but when the bones could be removed as easily as they could be from a brisket, they were.

As scarce as a bone-in brisket is, I was excited at the prospect of smoking one. At a beef class in Wooster, Ohio (my hometown, coincidentally), at the headquarters of Certified Angus Beef (CAB), me and a dozen pitmasters looked on as Dr. Phil Bass, CAB’s meat scientist, broke down a whole beef carcass. It had been dry-aged for 28 days, and we enjoyed some cuts cooked directly off the steer. A skirt steak was grilled a la minute and devoured almost as quickly, while chuck short ribs were enjoyed rare and sliced thin against the grain. The beef was spectacular. Which left us thinking one thing: what does a dry-aged, bone-in brisket taste like smoked?

I trimmed the excess fat from the brisket as we tried to convince the staff to smoke it overnight. They were all leaving the following day for a beef event, so I volunteered to do the cooking as long as I could take it home. CAB chef Michael Ollier attempted to sheath it in cryovac, but it was too large, proving just why the bones always come off nowadays. After struggling with the 23-pound behemoth, CAB thankfully agreed to ship it to my house, but it would have been one heck of a carry-on.

Back at home in my backyard, I fired up my steel offset smoker for an overnight cook. With the bones and the deckle still attached to the brisket, I knew it would be a long one. Another challenge was that it was dry-aged. That’s a process which enriches the flavor of beef, but it also dries out the outer surface of the cut being aged. In the case of a brisket, the outward surface is the fat cap that covers the flat and the point. The fat cap had dried out so thoroughly through the dry-aging process that almost all of it had to be carved away.

Wanting the dry-aged beef flavor to shine, I seasoned the meat only with salt. To keep it moist (remember, no fat cap) I sprayed it every hour or so with a mix of water, Worcestershire, and apple cider vinegar. The overnight portion of the cook was what I refer to as a sloppy cook. The overnight heat is an important jumpstart, but I wasn’t planning to stay up all night to hold the smoker at 275 degrees. I woke up every three hours to stoke a nearly extinguished fire. Once the day began, I maintained a 250- to 275-degree fire pretty well. Eighteen hours after it went on, it was finally done.

After resting for an hour at room temperature, I began carving. The ribs came off first, and I pondered with a couple friends what the marketability of “brisket ribs” would be at a Texas barbecue joint. The few morsels that came off were spectacularly beefy, with some good funk from the dry aging, but there wasn’t much to feast on. The deckle layer lies between the brisket flat and the bones (sorry, calling the brisket point the deckle is not accurate) and it was mostly fat, its of soft, buttery fat. I saved a good bit for chopped beef sandwiches, especially important since there was no fat cap. The flat was then revealed.

I carved the point away from the flat, and what was left was a large portion of lean meat from the flat that had very little bark. On a boneless brisket, all the rub and smoke would have formed a bark along the entire underside of the flat, but with the bone-in brisket, that surface was hidden and protected until it was sliced open. That meant most of the slices from the flat had little seasoning and a one note beefy flavor. Even after salting the beef the night before, none of the salt made its way that deep into the brisket. The fatty portion had a great, smoky bark, but the flat was about as boring as unseasoned roast beef. I chopped most of it with all that buttery deckle fat, which did make for some great chopped brisket. It wasn’t a bad consolation meal.

After trimming the brisket back at the CAB headquarters, and again when it went on the smoker, I posted photos on Twitter of the process. Most commenters were curious about the bone-in brisket, and some were downright covetous. They wanted to find a source to try their own. I’ll just say that I won’t put in much effort to find another one to smoke. The extra cook time and sacrifice of half the potential bark weren’t overcome by the novelty factor. The meat packers who first started boning out their briskets may have done it for convenience in packaging, but they also helped to create a more flavorful smoked brisket. Besides, I hear brisket ribs make a mean bone broth.

- More About:

- Brisket