Barbecue pulls at a traditionalist’s heart strings like few other cuisines, but it is no stranger to innovation. An offset smoker filled with brisket bathed on oak smoke has only been common across the state for about fifty years, but introducing science into a cooking process so reliant on fire and human instinct can be a tricky proposal. That’s what GE—yes, that GE—was hoping to do during SXSW in Austin last week.

The BBQ Research Center was in operation from March 14 to March 16, just across the street from Iron Works BBQ in downtown Austin. (Full disclosure: I was a compensated consultant for the project.) It was easy to spot because of the massive Super Smoker that anchored the corner of the site. When I first saw it, Evan LeRoy of Freedmen’s Bar in Austin was atop a moveable metal stairway unloading briskets from the twelve foot tall smoker. It didn’t make for a great first impression for a contraption that was meant to help improve the life of a pitmaster.

That’s not a slight on the machine itself. Fabricated by Sean Cusack, Lara Edge, and metal artist Thomas Van Houten of Oakland’s Sheet Metal Alchemist, the Super Smoker was a specimen of welded steel and glass. Yes, they even put heat resistant windows into the side of the cooking chamber, although heat-resistant wipers will be necessary on any updated models.

Our 15′ tall super smoker for GE at #sxsw is really coming together! Come visit us! pic.twitter.com/upYS5Ei0dN

— SheetMetal Alchemist (@SheetMetalAlche) February 25, 2015

Over the three days, LeRoy cooked brisket, ribs, chicken, sausage, and even tofu on the smoker working along with GE scientist Lynn DeRose. An eager crowd (about 1,300 per day) was fed samples of the finished product, but everything that came out of the Super Smoker was essentially an experiment.

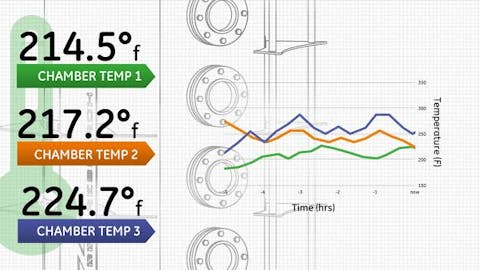

A series of sensors was mounted inside the smoker to keep track of temperature, smoke velocity, and relative humidity. That’s plenty more information gathering fire power than your average meat thermometer, but does any of that information help make better barbecue?

Let’s not pretend that barbecue cooks, from competition kings to backyard novices, haven’t been routinely using technology to improve their barbecue. The iGrill, a dual probe wi-fi enabled thermometer, and products like it are common tools in the barbecue arsenal. A brisket inside a fully automated pellet smoker requires less supervision than one in GE’s Super Smoker, and the BBQ Guru uses a thermometer controlled fan to keep a fire stoked without much personal attention. Who can blame a pitmaster looking for a helping hand?

Evan LeRoy found the sensors on the Super Smoker helpful, but only to a degree. He noted that he thought adding a water pan into the smoker would help regulate the relative humidity inside the smoker. A moist environment helps meat cook more quickly, and keeps it from drying out, but the water pan didn’t do much. It was really the wood providing the moisture. “You could really see [the humidity] spike when we added wood,” LeRoy told me when I visited the Research Center. DeRosa noted the same phenomenon in her daily blog of the event. “We learned that by giving the fire a constant feed, one or two pieces every 30 minutes, we were able to regulate the humidity much better.” Chalk one up for the Super Smoker.

The smoke velocity was also helpful in tracking whether the smoker had a good draft. For heat and smoke to transfer to the meat, air has to move freely from the firebox to the exhaust. This metric proved necessary because of the major design flaw in the smoker. In order to amplify the experimental nature of the smoker, the design was done vertically rather than a more traditional horizontal smoker. (Creating a visible advertisement to the site may have also been a factor in the design.) But LeRoy said it was the most difficult part of the experiment to overcome. Heat rises, so the flow of the smoke up to the exhaust was natural, but it would normally flow around the curved surface of a brisket in a horizontal smoker like air around an airplane wing. In the case of the Super Smoker, the hot air hit the bottom of the briskets like a conversion van speeding through a nor’easter. The underside of the briskets took the brunt of the heat, and they could also create serious smoke blockage if not arranged properly on one of the smoker’s six cooking shelves. LeRoy noted that he even flipped a few of the briskets for even cooking.

The hardest part of putting out great barbecue is knowing when it’s done, and other than a temperature readout, the Super Smoker didn’t help much. Touching each brisket and rack of ribs was still required to know for sure if it was ready to pull off.

Despite any challenges with using an unfamiliar smoker, the brisket that LeRoy produced with the Super Smoker was very good. After having eaten at Freedmen’s recently, I’m not sure that the Super Smoker allowed him to make his brisket any better than what comes off his analog smoker at the restaurant. It might sound anti-climactic, which made me think, what does GE get out of it? Lynn DeRosa addressed that in her blog. “We want to provide our operators with the ability to see how their manufacturing process is performing, so they better understand how to optimize their operations…the sensor-enabled smoker is an analogy for our manufacturing equipment.”

Aaron Franklin, owner of the incredibly popular Franklin Barbecue in Austin, was eager for information during the BBQ Science Center’s final panel discussion (which I moderated). He was as curious about the design and the sensors as the now sated crowd. Franklin talked about trial and error and the importance of human observation in determining a brisket’s doneness, but was intrigued by the idea of humidity and temperature readouts to help train staff who haven’t yet gained the experience to do it all by feel. Franklin is no stranger to talk about science’s role in barbecue. In a video produced by PBS last year (above) he discussed the role of data collection versus experience. “I think good barbecue is a balance between science and just natural gut instinct.” Franklin added that, in the end, good barbecue requires a human touch. “Feel trumps any black and white number or equation that you could possibly have. If something’s not tender, it’s just not tender.”

- More About:

- SXSW