As I’ve talked about before, smoked brisket wasn’t always the cornerstone of Texas barbecue. Before the beef purveyor IBP started shipping individual cuts to meat markets, these establishments (if they smoked meats at all) were cooking the entire beef forequarter. This meant they were smoking both the cuts familiar to us now–short ribs, shoulder clod, and brisket–as well as cuts that don’t see the smoker quite as often these days, like the chuck roll and the beef shank.

When you buy a chuck roast at the grocery store, you’re essentially getting a piece of the chuck roll. The retail chuck roast is normally sliced an inch and a half to two inches thick and weighs in around two pounds. Due to the considerable amount of collagen in this cut, it requires a long cooking time to break down and tenderize; the most common method of cooking is to braise it in liquid, roasing it at a low temperature to make what we know as a good old fashioned pot roast.

But I wanted to experiment with this cut. What would happen to it in a smoker if it’s cooked with only dry heat? Is the chuck marbled enough to keep the meat juicy even without the moist heat of braising? While choosing my cut at the butcher’s counter, I also noticed the beef shank. As I said, this is also part of the forequarter, another cut seen during the early days at Central Texas barbecue joints. I bought them both, and headed back home to light the smoker.

After nearly eight hours of continuous smoking at around 225 degrees, the chuck roast was still not tender. The beef shank had pulled back considerably from the bone, but it too was still pretty tough. For reference, I had also included a large rack of beef plate ribs into the smoker at the same time, and they were buttery tender by this point.

Slicing into the chuck and shank told me immediately that just dry heat wasn’t the right method. The meat wasn’t juicy and despite it’s long day in the smoker, it was still a bit undercooked. I figured these cuts needed moist heat to get to the sweet spot, but I wanted to try one more experiment: I put two more raw chuck roasts into a 275 degree oven (I turned to the oven because it provided a consistent temperature) and placed a probe thermometer in each of them. Once they reached 180 degrees, I wrapped one with foil and added some water into the pouch to braise it.

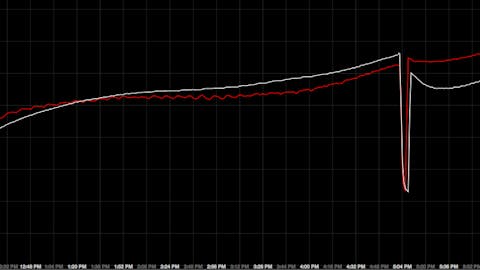

You can see the dip in temperature in the chart above which corresponds to both chuck roasts being removed from the oven. The unwrapped chuck recovered much more slowly, and took nearly thirty minutes longer to reach 205 degrees. In the end, both of them were dry, and only edible when sliced thin and simmered in beef gravy, which wasn’t the worst sandwich I’ve eaten.

The final test was the smoke/braise technique. The dry heat of the smoker wasn’t enough, so I had to introduce moist heat, or braising, into the cooking equation. Doing so at 180 degree internal temperature had already proven too late, so I moved it up to 150 degrees. This time, instead of buying a sliced portion of chuck roast from the grocery store counter, I went to Rudolph’s Meat Market in Dallas to get an intact chuck roll. I purchased a six pound piece and nearly an entire beef foreshank.

At home I cranked the smoker up to 275 and let both cuts go until they registered 150 degrees internal temperature which took about five hours. I then moved them to a roasting pan with a little beer for a braising liquid, covered it tightly with foil, and let them go for six hours until both the chuck and the shank were tender to the touch.

The result from the chuck was something extraordinary. I never thought I’d find a cut to rival brisket for beefiness and juiciness, but this one was a contender. Also, keeping the chuck roll intact allowed it to easily be sliced against the grain into thin and tender slices. The beef shank was easy sliced too, but pulling it like a pork shoulder was even better. I had found success. Oh, and did I mention that both of these cuts are currently cheaper on the wholesale market than brisket?

If you’re looking to experiment with a new cut of beef, then I’d recommend the chuck roll. It was fun to watch the beef shank’s considerable transformation during the cooking time, but it required a lot more picking and choosing to get good bites. Nearly the entire chuck roll was edible, and a bonus was how good the cold slices tasted the next morning right out the fridge.

Smoked Chuck Roll

Take one six- to- eight-pound chuck roll, and thoroughly coat it with a rub of 3 parts black pepper to 1 part salt. Smoke at 275 for 5 hours. Near the end of the smoking time, preheat the oven to 275. Pour two cans of beer into a roasting pan with a rack. Place smoked chuck roll onto rack and cover tightly with aluminum foil. Cook in oven for 6 hours or until tender. Reserve braising liquid and chill. Slice beef and serve immediately, or chill overnight for smoked Italian beef (see recipe below).

Smoked Italian Beef

Chop a large onion and sauté in a large pot until soft. Skim fat layer from reserved beef braising liquid and discard. Add liquid to onions. Pour in two 32-ounce cartons of beef broth. Add 2 T dried Italian seasoning, 1T garlic powder, 1 T salt, 1t onion powder, 1t white pepper. Bring to a boil, then simmer for 10 minutes. Slice chilled beef thin and layer into a baking dish. Bring broth back to boil, then pour over sliced meat and cover tightly with foil. Let sit for ten minutes to warm beef thoroughly.

Serve on sturdy rolls with giardiniera, and spoon broth over sandwich, or dip loaded bun completely into broth.