On April 10, 1936, Tom Foward and Callie Lilly found themselves engaged in an eighty-mile late-evening chase with the local police. The African American couple from Dallas had fled an altercation at a service station in Richland, just south of Corsicana. As the Corsicana Daily Sun described it, the high-speed pursuit sounded like something out of a Hollywood summer movie.

Sheriff Rufus Pevehouse stated that he and [Deputy Sheriff Jack] Floyd gave chase on the highway and almost caught the speeding automobile near the underpass in North Corsicana, but that the roaring car, making approximately 100 miles per hour, drew away from the local pursuing automobile and disappeared within a few miles. After the alarm was radioed by Dallas police officials, a squad car gave pursuit south of Dallas but lost the fleeing negroes when the negroes’ car darted in front of a passenger train crossing the highway and the officers were forced to stop. Another Dallas police squad car “jumped” them in Dallas but was outdistanced and finally the sought couple were caught in a traffic jam in North Dallas, according to Sheriff Pevehouse.

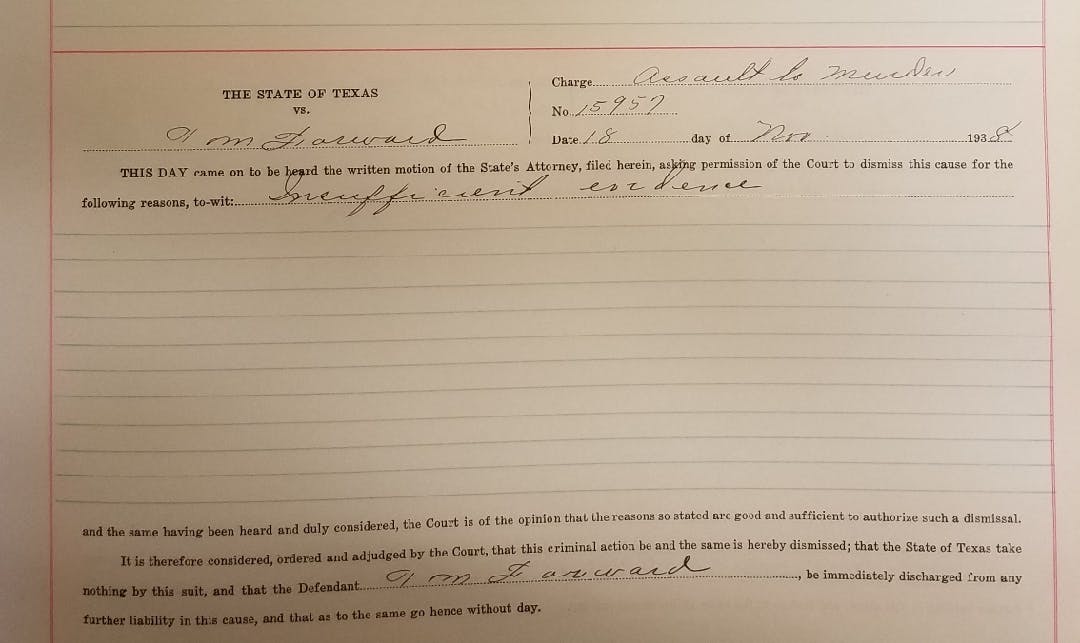

The couple had fled from a gas station operated by J. T. McGee, who admitted to the district attorney that he’d thrown a water bottle (likely made of glass) at the car after an argument about fuel prices. In retaliation, Foward fired his pistol over McGee’s head, striking the station, according to McGee’s account. The Daily Sun didn’t provide Foward’s description of events, but he and Lilly were released on bond the following day. Further adjudication of Foward’s “assault to murder” case would have revealed more details, but it never got any closer in the courts. Just a couple weeks back, Navarro County’s current district clerk, Joshua Tackett, dug up an image of the charge dismissal document from 1938 that revealed why the case was dropped: insufficient evidence.

This odd criminal case provided some benefit to hungry Dallasites. While he was out on bail in 1937, Foward, an experienced pitmaster, opened Beaumont Barbeque in Dallas. A couple years earlier he had opened a joint by the same name in Houston. That spot closed in 1939, but the one in Dallas, in the northwest part of downtown, enjoyed more longevity. Foward ran the Dallas enterprise for thirty more years, but I only know about this barbecue joint because of a series of publications known as the Green Books.

In the thirties, newly paved highways and inexpensive automobiles provided the opportunity for hundreds of thousands of Americans to enjoy cross-country road trips. But the route catered to white Americans. According to writer and historian Candacy Taylor, 44 of the 89 counties that lined the iconic Route 66 were home to “sundown towns,” communities where non-white travelers weren’t welcome within city limits after the sun set.

In 1936, Victor H. Green, a postal worker from New York City, created a guide to help African Americans safely travel in his hometown. Three years later he published the first guidebook for African American travelers across the country: The Negro Motorist Green Book. Published more or less annually until 1966, the books listed lodging, service stations, and restaurants safe for African Americans to patronize during the Jim Crow era. “Now we can travel without embarrassment,” was the motto printed inside each copy, though the book’s buyers certainly knew that the publication might also spare them humiliation and physical injury.

For African Americans traveling through Texas in the late thirties, the Green Book listed only two barbecue joints that were safe to visit: Foward’s Beaumont Barbeque, in Dallas, and Long Bar-B-Q, in Beaumont, owned by Edward Long. That’s a pitiful number, but it’s not as if other cuisines did themselves proud. In 1939, just five Texas restaurants were listed as safe for African Americans, and by 1960 the number had grown to a mere twenty. Thankfully, a hungry traveler could get ribs at a couple of them.

Neither of these two African American–owned barbecue joints remains, but Billy McDonald, who runs Mac’s Bar-B-Que, in Dallas, remembers Beaumont Barbeque. McDonald’s dad started Mac’s in 1955 on Young Street, when Beaumont Barbeque was across downtown on what was then called Orange Street. Dallasites might know the Wells Fargo branch bank that sits where Field and Griffin streets merge. That’s about the spot where the barbecue joint was located. McDonald told me, “They were a sandwich house, just like what my [dad’s joint] used to be at the beginning, back in the fifties.”

There’s not much more information than that about Beaumont Barbeque, but thankfully we have a fair amount of detail about Long Bar-B-Q. Robert Patillo, owner of Patillo’s Bar-B-Que, in Beaumont, provided some insight. Patillo’s, which is the oldest family-run barbecue joint in Texas, bounced around locations in Beaumont in its early days, but for a time in the thirties, the Patillos served their famous links from a food stand next to the Star Theater on the same block of Forsythe Street as Long Bar-B-Q. “Long Bar-B-Q was across the street from the old Star Theater, the only black theater Beaumont had back in the day,” recalled Patillo. Forsythe Street was the center of African American life in the city. “They said on Saturday nights you could hardly walk down that block of Forsythe,” Patillo told me, saying it was too packed with people to allow for cars. “It was like Beale Street up in Memphis.”

Long Bar-B-Q was first listed along with eleven other barbecue joints in Beaumont’s 1935 directory. Of the eleven, eight were black-owned. Patillo described Ed Long’s sauce as being a little sweeter than his family’s recipe, and he figured that Long probably used the Patillo family’s meat grinder, which his grandfather let nearby businesses borrow, to make their links.

In 1943, Beaumont suffered a race riot. Forsythe Street and other black neighborhoods were a target of white dockworkers who’d heard rumors of a black man assaulting a white woman. Businesses were destroyed, and three people were killed. It’s unclear whether Long Bar-B-Q was damaged, but in 1944 the Pittsburgh Courier, an African American newspaper, announced, “Ed Long has recently remodeled his café and barbecue pit on Forsythe Street. Earl Bill is the efficient and amiable manager.”

No one seems to know how these two restaurants got added to the Green Book, when other restaurants that should certainly have qualified—think of those eight other black-owned Beaumont barbecue joints—didn’t. While conducting her research, Taylor talked with Ollie Gates of Gates Bar-B-Q, a black-owned barbecue joint that opened in Kansas City in 1946. “One of the things he told me was that it was unusual for a black business owner to advertise,” she said, reasoning that, “the bigger some of these businesses got, the more threatening they were to white folks.” Robert Patillo was candid about why his family’s business wasn’t listed in the Green Book. “My grandpa[‘s barbecue stand] was a little bit further down [the street from Long Bar-B-Q], and he catered more to white patrons,” Patillo said. With some regret, he added, “He had a back room for the black patrons, and they didn’t like that.”

It’s not clear when Long Bar-B-Q closed. Long’s widow, Georgia, ran the place on her own after his passing in 1960. It remained in the Green Book until the final edition, in 1966, right along with Beaumont Barbeque.

The menus and stories and recipes of the two barbecue joints have been lost to time. The only newspaper clippings available about Beaumont Barbeque show what thieves stole when they broke in, mostly cigarettes from the vending machine. But for three decades, Foward and Long provided the only two Texas barbecue joints that African Americans around the country knew were safe to visit.

- More About:

- Black BBQ