Owner/Pitmaster: Serious Barbecue

Owner/Pitmaster: Serious Barbecue

Age: 45

Smoker: Wood-fired Offset Smoker

Wood: Red Oak, White Oak, and Pecan

There isn’t much that Adam Perry Lang hasn’t done in the world of barbecue. He has authored multiple books on barbecue including Serious Barbecue, BBQ 25, and Charred & Scruffed. He found success in a brief stint on the barbecue competition circuit and is now a member of the Barbecue Hall of Fame. In 2003 he became a barbecue pioneer in New York with the opening of Daisy May’s. Now he’s working on bringing barbecue to the other coast in a project under development in Los Angeles. Not to mention taking barbecue to London with Barbecoa. But his path into barbecue didn’t take the usual route.

Barbecue is now what drives Adam Perry Lang, but right out of culinary school was working in some of the finest kitchens in New York before extensive study in France. He then revolutionized the way America looks at dry-aged beef with Robert’s Steakhouse in New York before taking it to a scale never before seen at CarneVino in Las Vegas.You could say the man gets around, but I had the opportunity to get his full attention during a northern California road trip. We chatted in the car on our way to discover Santa Maria style barbecue.

Daniel Vaughn: At what point in your professional life did you realize that barbecue was the direction you wanted to go? Was there a turning point?

Adam Perry Lang: There was. I think about that often and I think there was some small micro-triggers that steered me in that direction, but one of the biggest was the movement within my set of fellow cooks towards what people term as molecular gastronomy, and a real shift towards automation. I never quite cozied up to using tweezers. I felt that it was so disconnected and so anti what I actually got into it for. I just started to gravitate towards natural forms of cooking, specifically with fire. Since I was a kid I was drawn to fire. Just understanding it, staring at it, whatever. I’m a natural born pyro I suppose, but for me I always describe it as a conversation with fire in that you can’t completely control it.

DV: When did this shift happen?

APL: I was working as a private chef in New Mexico and there was lots of displaced Texas ranch guys. On our down time this guy would bring out on a fork lift, this incredible custom-made pit as a classic offset. I ruined a lot of meat, but I had a lot of fun doing it. I feel like certain things were funny. Like when it was time to season his pit he emptied his wife’s whole spice cabinet and seasoned the actual inside.

DV: He literally seasoned it?

APL: He literally seasoned the entire inside of the pit. I was just like, ‘That doesn’t look right.’

DV: You were already skeptical?

APL: Well I wasn’t skeptical because you know, may I forever be a student, but you know the reason why I was having trouble with the barbecue is because we had some very cold nights.

DV: Where were you in New Mexico?

APL: It was a ranch in between Santa Fe and Albuquerque. I mean in the middle of nowhere. The fact of the matter was I didn’t understand the dynamics of the airflow and heating up the pits so the wood was not fully seasoned. Because it was so cold, the smoke would just try to find any type of hot spot in the air so it would go out of the box. I didn’t really understand the thermodynamics at that point so I ended up being more smoky than the actual barbecue. It made me fear trying to learn that much more.

DV: What kind of cuts were you trying to cook?

APL: Typical cast of characters. Brisket and pork shoulder and ribs.

DV: Did it taste good enough for your client?

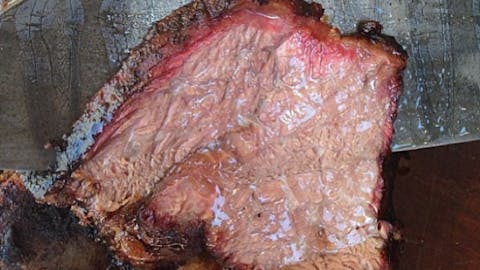

APL: They weren’t into it in general. It was really more for me. For me it wasn’t the burning, it was really more the creosote. Just the lack of burning a clean fire which is what I learned to do and what I prefer now. It’s that blue smoke and lots of airflow, lots of momentum, building up that coal base and having that heat drive through over the barbecue, over the meat. Back then I looked at it like most people do now as smoking. I don’t smoke meat now. I cook meat using wood with fire and so I’m not looking for smoke. Smoke happens. Back then my understanding of what barbecue was is very different than what I see to it as today so I’m striving at a different goal.

DV: Did you grow up with any specific understanding of barbecue, either from a regional standpoint or something that you cooked when you were growing up?

APL: You have to understand where I grew up which was in Long Island in New York. I call it Yankee barbecue and fight tooth and nail to call it barbecue because that’s what we called it, but it was really more direct grilling. If we were to take a whole fantastic beef tenderloin and not trim it and throw it directly on the grill and close the lid, it gets really fantastic flavors. But the only brisket that was done in my household was braised apparently with my grandmother’s recipe. And a lot of times it was as simple as here you go, here’s the recipe pal. It’s one can of Coke, one packet of Lipton onion soup mix, and one jar of Heinz chili sauce. At the end of the day, we can talk all day about how I prepare this and this guy does that, but how does it f—— taste? That’s the bottom line.

DV: Where did you eat that first bite of southern barbecue that really registered?

APL: I think in snapshots. It’s not specifically one place. I don’t think there was one rib or something that – I’m still doing it, to be frank with you.

DV: I guess what piqued your interest? It doesn’t look like you were smoking briskets back home.

APL: I think going to Arthur Bryant’s in Kansas City and having brisket that was sliced right off the slicer, piled high and not even putting the sauce on it and just not being able to stop myself. And at that point I didn’t understand the sauce because I was looking for sweet. Now I freaking love Arthur Bryant’s cumin heavy sauce. But back then, the concept of having something so moist and something so sweet from the smoke was just absolutely incredible.

DV: Did you go to Kansas City for the barbecue?

APL: Definitely. It was maybe 2000, 2001? I mean it’s not that long ago that I really started to get obsessed.

DV: Sounds like it’s an obsession that at least has some staying power.

APL: I’m just getting more and more appreciation for what’s good and what’s simple and I’m becoming more and more harsh in my judgment. I just have no patience for chewing dry meat. I just spit it out. I just don’t want to waste my stomach. To get a good point and flat is very difficult in a restaurant setting.

DV: So back in 2000, 2001 back when that Kansas City trip was, what were you doing professionally?

APL: Private chef. I catered to one individual.

DV: Besides the private chef gig that you had, you worked in a lot of other kitchens as well.

APL: My whole cooking education started at the Culinary Institute of America which is a great foundation, a great base, I’m glad I did it. Then I jumped right into working with Daniel Boulud at Le Cirque and then I opened the restaurant Daniel with him. Intense learning time. Then jumped right into a sous chef position at a place called Chanterelle, another four star New York Times type of place. There was only like five of them in the city at that point. You know, you kind of work the circuit, become part of this French mafia also. Once you marry into a chef or a school which is Daniel Boulud for me, at that point your whole world opens up because what happens in these kitchens, you kind of trade help and in a way it diffuses knowledge into other kitchens

DV: What was your first foray into doing barbecue professionally?

APL: Daisy May’s.

DV: So how did that job come about? What was your initial role in that restaurant?

APL: I wanted to go into business for myself. Who do you go to? You go to someone that you trust, that believes in you and shares your vision and trusts you. So there he is, there’s my best friend and his dad and I want to open up a barbecue place and part of the thing was, “Hey I happen to be opening up this gentleman’s club and I need to put a restaurant in there. Can you help us with that?” I’m like, “Hell yeah. Let’s do it.” He’s like, “What do you think? What should we put in?” It was very natural for me to say, gotta do testosterone, let’s do a blow out steakhouse. Like dry age and let’s do it.

DV: So this was happening simultaneously with Daisy May’s?

APL: Simultaneously. So I’d be opening up my first business and then I’m also going to open up my first steakhouse in this gentleman’s club. I just basically had free reign to do whatever I wanted. I’m a craftsman in nature, I don’t like the dependence of buying dry age meat from somebody just in general, just the concept. So I was like, “I’m going to learn dry aging. I’m going to hang out with the guys in the Bronx and start talking around and figure out who built Peter Luger’s dry age room or who did this?” Piece it together and make it a living experiment. Initially it really wasn’t super popular in there, this dry age thing, and everyone was just going for the strippers.

DV: What was it called?

APL: Robert’s Steakhouse. We got a bangin’ review from Jeffery Steingarten in Vogue. He’s such a skeptic. He looks like grumbly, but man God bless him. If there’s ever anybody who should ever ask any questions to someone who’s really doing it, Jeffery Steingarten is going to weed out the bulls—. And I was all about the food. I was all about the process. I was all about my discovery and I was all about what was happening. It was the right time. It was like perfect storm s— and he’s just asking me a million questions and I’m just spilling the beans. That’s how I really came across the extended dry aging. We extended out past fifty weeks, a year. And Jeffery Steingarten was the first person to eat that steak and I did not know if we would die.

DV: For any food writer looking for a story line, that’s like striking gold. To find a fantastic steak house inside a strip club, but let’s get back to Daisy May’s. What year was that that it opened up?

APL: 2003.

DV: When did the reviews start rolling in on Daisy May’s?

APL: Simultaneously, but before then I was really nervous because we opened up the first day, all your friends and family come in. We put $1,000 in the register. You know great, but then the following days I’m doing like $400 a day, then $250. I’m looking at my partner only three weeks in like “S—!”

DV: You had a lot of meat left over at the end of the day?

APL: Yeah you know. It’s nutty. I’d have just trays of meat, just giving it away to staff and I knew we were doing great stuff. My partner was like, “Maybe we should think about advertising.” I was like, “I do not want to advertise.” That’s like, desperation, you know? I met a girl through Food Arts Magazine and she’s like, “Hey I want to start up my own PR company and I’d like you to be my first client.” It was $500 a month or something like that and she gets me across Florence Fabricant’s desk at the New York Times. She is like an icon, out of all the food writers, she was one of them just no bulls—. She calls me up. Strict as like my strictest teacher in elementary school. “Hello. I hear you’ve started barbecuing.” I’m like, “Yes,” and I started telling her my process. “I’m sorry, I’m going to have to come down and see that you’re burning with real wood. I’ll be down in thirty minutes.” She comes down, doesn’t say much to me, looks for my burning wood. I made this custom fire trap thing in Manhattan. At that time I was scraping the bark off the wood because I heard it made it bitter, some stupid stuff like that. I was scraping the bark with a big cheese knife. I was like, okay you peel carrots, you put them into a stock. You might as well peel the wood. So I was blowing through wood. And my guys, one day I catch them breaking up a treated lumber pallet to burn I was like, “No, you don’t get it. We’re not just burning stuff. We’ve got to get the proper wood.” But these are the fun, exciting stories. I’m waking up going, “Oh my God, did somebody eat the pressure treated wood?” Then I start doing research thinking there’s arsenic in that s—. Then at that point I was really getting no sleep.

DV: So was there anyone cooking there at the beginning besides you?

APL: No. This was all me. Again, working up to my second back surgery, dragging my knuckles on the floor, loving every minute of it. Then Florence Fabricant wrote this piece which to me was the catalyst of all my press. It was titled Where There’s Smoke There’s Desire. It was a little “on the menu” type of piece. I was there in my gingham shirt or something cheesy.

DV: With your bark scraper?

APL: No, no one knew about that. You’re the first. Breaking news. So then from that point on, boom, stanchions outside. I mean, we couldn’t control it.

DV: It was immediately after that got published?

APL: Yeah. I mean, we couldn’t hold onto product. We were selling out, like you’re supposed to do with barbecue. It was gangbusters. I didn’t know that selling out was good. I thought like, “I got to increase the volume.”

DV: Lost revenue, right?

APL: Yeah. So I began to start squeezing more stuff into my smoker, and then I wasn’t getting bark and crust and then I was just, like, “I’m sorry. I slipped into it.” I just said, “You know, I can’t start serving this stuff and doing this.” And so I backed off of it. You know that happened a couple of days, and then I just backed off. We start at 11:00 and sell out by 2:00.

DV: That had to be a tough conversation to convince your partner that you weren’t going to make more food.

APL: We had a very equal partnership, so it wasn’t like I was driving the ship. My rent was certainly cheap enough. We built the place for under $300,000. Also, we designed the place with tongue-and-groove cedar on the walls. We opened up with nothing on the walls. I said, “We’ll figure it out. We’ll put on whatever.” We weren’t going to put up wagon wheels and license plates, what people think it should be.

DV: What were the menu specialties?

APL: My beef short ribs, which was a signature. At first I cooked all these damn things, so my brilliant idea was to then cube it up and put it on a skewer, and then reheat it in a convection microwave. What happened was that’s what I started out doing, but then crowds came and I didn’t have any time to prep it, so I was just hacking off beef ribs.

DV: You did whole hog there, right?

APL: I wouldn’t call it a hog. It was more like a piglet. Dressed they were about fifty pounds. We would throw it into the cooker and about six and a half hours later—you’d give us a couple of days in advance—I was going through twenty-five or thirty of those a week at $400 a pop. What I loved about it and the big thing about cooking in general is the socialization with it.

DV: So you had a great review then some quick success after that. How long were you a partner there?

APL: Well, it’s still operating and bless ‘em, you know? Different goals, two different partners. I left for the UK around 2008. I held onto it for a while, but in the end it wasn’t going to work with me out there.

DV: When you headed off to the UK, is that when you opened Barbecoa?

APL: Well, in between yes. But Mario Batali had approached me and says, “Hey, can I entice you into a partnership? We’re looking at doing this steakhouse. Maybe we’ll do more. We tasted your stuff, me and Joe [Bastianich], and I’d like you to meet him.” I opened up CarneVino with them in 2008. Right around then the whole world bottoms out. The whole financial thing. The world turns upside down, and projects like Dubai and all these projects all of a sudden with limitless funds now suddenly gone.

DV: But CarneVino survived?

APL: It survived because we’re delivering the goods. I mean, there’s no one doing what we’re doing with the volume that you need to be doing to turn over on that type of product.

DV: So you’re playing around with all this dry-age stuff. Dry-age and barbecue, have they ever met successfully?

APL: It doesn’t work. The transformation of flavors that occurs with dry-aging is a curious one. It just so happens that those same compounds that you develop with the dry-aging process does not lend itself well to a long, low cooking process. What happens is that they develop some real livery overtones and flavors that just aren’t pleasant. So, yeah, sure I played with dry-age briskets and all sorts of things, but basically, at the temperatures that you’re cooking to, your protein’s going to be shot. There’s only a certain point at which the fat and collagen will take you.

DV: CarneVino in 2008, then headed out to London?

APL: Barbecoa was like something that I really wanted to get going with Daisy May’s in the back of my head. It was like a convergence of barbecue and my dry-aging. I met Jamie Oliver, and we fell in love. I said, “Let’s do a project together.” Within six months we hammered out a deal and I’m on a plane. It was an amazing adventure, because at first we were going to open up in Germany and then as soon as the wheels land in the UK, the whole Savings & Loan scandal happened. Everybody’s calling loans, and Jamie’s like, “Mate,”—you know we had all these backers we were going to do this stuff, he was like, “Mate, I believe so much in this thing that we’ll work it out. We’ll find the money.” It was a scary time, but that’s what you do when you’re young. It’s not that far ago, but young enough where you’re like, “How am I going to feed the kids kind of thing and still maintain my integrity with the food?” So, I’m over there, and we’re brainstorming doing all this great stuff and around the same time he’s about to catapult into a whole new realm of fame. He had just less and less time. I was the driving force behind Barbecoa, but is it what I initially envisioned? Absolutely not. It was a bit more slick than what I had planned. Still, it was a smashing success on so many levels, but Jamie’s off doing his thing. I’m dealing with all these other very aggressive corporate types. It was time to make like Tarzan and keep swinging.

DV: You had some success in competition barbecue as well, right?

APL: My first barbecue competition was a bet between myself and one of the heads of marketing within the pork council. He said, “Chefs don’t know how to cook barbecue. You want to show your stuff? You come cook barbecue in Des Moines, Iowa.” You cook a whole hog: ribs, pork loin, and shoulder. There were eighty-eight teams. I was the only one from New York. Our bet was like, “If I lose, for a year I have to kind of wear a ‘chefs don’t know how to cook barbecue’ t-shirt.” And if I won the competition, he’d have to wear an “I love New York” hat.

DV: You had to win the whole thing to win the bet?

APL: Yeah, I had to win the whole thing, so I was like, “I’m going to go in, and I’m going to f——- win this thing.” This is one of the most beautiful things about the barbecue community, which to this day I’m still friends with all these people. I didn’t have a rig. I didn’t have anything. I called a couple people within the pork council, and I met Mike Tucker from Hawgeyes Barbecue. He gave me a Horizon cooker. Another friend David Heinz gave me an RV. And for everything else I went to Cabela’s, and I dropped $1,200 on all my supplies and everything.

DV: What was the reaction from the other competitors at the beginning?

APL: The reaction was at first a lot of people just didn’t really acknowledge me there. When were in the pre-meeting someone said, “We got a guy from New York City!” And someone goes, “Get a rope!” I was scared.

DV: This was your first barbecue competition?

APL: My first barbecue competition, and I won it. I went in and got the first perfect-score in ribs, a 180. I got second in pork loin. I got sixth in whole hog, I think. I killed it. I automatically got everybody’s attention. Then it qualified me to be in the American Royal, which I got first place for my pork shoulder in the invitational.

DV: And that was your second competition?

APL: In between, I also did something called the Butt to Butt, which I got second in. It’s everybody who won first place in a national competition with pork butt, seven or eight teams. You all meet in the middle of this field, like Field of Dreams s—. I came in second to Candy Weaver. I don’t know if you know her—great cooker. I don’t win them all.

DV: Sure, but you go onto the Royal, which you won an invitation to. How’d you do with the rest of the stuff?

APL: I did really well. You know the way I look at it with these things, I don’t remember the exact placement, just the fact that I got first place in my shoulder, and I won by two ten-thousandths of a point above one of my heroes who is Johnny Trigg. Then, I got a perfect score on my brisket in Huntsville, Alabama for the Rocket City BBQ.

DV: Would you have continued on if you would have done really poorly at the first competition?

APL: Who the hell knows? I caught the bug, because all of a sudden I was welcomed into this community, which I love.

DV: So the reaction then after you won?

APL: They were just like, “We just wanna know what you do,” and not in an aggressive way. You felt like you made your bones kind of thing. For me, I like to belong, and I felt that I always draw the same similarities with cooking in France, because until you make your bones, it’s like the most miserable place to be. I was really sick of telling my story, having to say, “Well, I’m from New York and it’s kind of like Kansas City, and what I’m trying to do is Texas style.” No, it’s my barbeque. Yeah, I use some sambal chili sauce instead of Tabasco in my sauce. Or I’ll use orange blossom honey as opposed to something else. It gave me permission to do what I wanted to do. Then I got into the Jack Daniels in 2006. Funny story about the Jack, this is one of those chefdom things. I did really well. I got third place in ribs, seventh in my shoulder, but I bombed in brisket, which I thought was one of my best briskets I’ve ever done. So, the first category is chicken, as you probably know. And I got really cute with that. I did great chicken. I went to do the white meat and the dark meat, the thighs. But I decided to take the skin and make it so crispy and then cut it up and put it on there. I turned in my chicken, and I’m getting ready for the ribs. A guy comes up and he’s like, “I’m sorry sir, but we’re going to have to disqualify you.” I’m like, “What the f— are you talking about? I’m sorry sir, I don’t know what you’re talking about.” He said “There was a foreign object, you had potato chips in your chicken box.” I’m like, “Sir, I will tell you this right now: That is crispy chicken skin.” And we go back and forth. Anyway, I ended up getting 11th in chicken after it was sitting there for forty minutes.

DV: When did the first book happen?

APL: Serious Barbecue came out in 2008. It sold well, but the publisher stops pushing it after a while. I got the option to get the rights back, so I went for it. It was an opportunity to own my book and I saw it as a wonderful opportunity. Now I had to figure out how to become a publisher. I said, “Here’s an opportunity for me to now put up or shut up.” I self-published it and it became my brand, my raft in between restaurants. So I’m a bit of like a ship without a port right now. I’ve got my place in Vegas, but I don’t really have my Daisy May’s or anything like that. I sold my interest Daisy May’s and in Barbecoa and I moved back here [to Los Angeles]. I’m going to open a place, but I’m trying to get the right deal together.

DV: Your cookbooks are so much about messing with the meat while it’s cooking. You’re flipping and basting, but so much of barbecue itself is an inactive process with the meat. You’re not really fiddling with the meat a whole lot.

APL: That’s why I think it’s cool. It’s more about fire management.

DV: Now you’ve got the fire to play with so you can leave your hands off the meat?

APL: It fits my personality, I suppose. With the meat, I’ve learned to lay off it a bit more, particularly with this cooker that Aaron built for me. It’s less temperamental to my active style because when I got the freight train of heat underneath, heat’s rising so I don’t have recovery issues. For me it’s less about cooking meat and more about fire management, the process, and that’s what I love. You want the smoke to roll over the meat in the most clean, fast way. You want that right balance of humidity. I use a ton of wood, because I just don’t want to choke anything. I want the smoke rushing over the meat because stagnation, that’s just gonna settle with the moisture on top of the meat and make it sooty. I just don’t want to eat ashtray s—.

DV: You’re working on getting a permanent spot in LA, but in the meantime you had a Serious Barbecue pop-up in Hollywood last year and again this year.

APL: That was basically me taking a lot of time discovering California and needing to do something because I was getting antsy. I also wanted to do something really pure. I was inspired by that movie, that short documentary, Cut/Chop/Cook. I just wanted more meaning to it. It was just some honesty and purity to that movie that made me say, “I want to build a burn barrel.” I wanted to do direct/indirect cooking. I’m a huge believer in these flavor bombs and also a covered grill system. I enjoy that cooking with the J&R equipment. It’s my only equipment out there that won’t melt in on itself. And these guys will literally build whatever I want. They’re expensive, but they’re worth every penny, and they believe in me enough to listen to my crazy ideas. I said, “I want to create this thing where meat can drip on the coals, but it’s a cabinet and I can close. Of course they’re thinking like everybody else like, “Well, you’re gonna be up a lot. You’re gonna be tending the fire a lot.” I say, “That’s exactly what I want because very few people are doing that. I want to really see if that little extra bit creates a difference with the barbecue.”

CUT/CHOP/COOK from Joe York on Vimeo.

DV: Did the pit work how you expected?

APL: The second night of the pop-up we had a fire. No one knows about that. I’ll tell you what happened. I get into the routine of cooking with my guy, my late-night guy, Big Rob. He’s 375-400 pound guy. I’m showing him how to work the pit, and finally I was like, “Look, I can’t stay up another night. I gotta sleep for three hours. You got it?” “I got it, chef.” “Okay, great.” Right when my eyes close, bang, bang, bang! “Chef, the fire.” I’m like, “Oh my god.” I’m in the second day, and the fire department’s never seen anything like this type of thing. We run up there. “Okay, you shut down all the dampers.” He’s like, “Yeah, because we had a back draft.” He opened it up and basically the fat had welled up so much on the coals that it was just right at flashpoint. And then, boom! He just slammed the door. He was very smart. It was a vacuum. It was just so oxygen thirsty. The temperature dials are just off the charts, 700 degrees in that cabinet. And I was like, “Okay. All right. Calm down. Relax. Let’s just wait it out.” I waited like a solid 45 minutes. Nothing was ruined because he caught it fast enough. I said, “Okay we shovel out all the fat, all the ash.” We totally started out fresh.

DV: I guess the meat was almost done at that point.

APL: It wasn’t though. If I had briskets in there, forget it. But it was beef ribs, and the bone had so much protection for the meat. The bone captured the brunt of the direct flame, and he shut it down fast enough. And my god, beef ribs, you can drag them behind this car for two days and then rain storms and freezing temperature, hot temperatures, and you can make a pretty decent beef rib. They’re pretty hard to f— up.

DV: The initial purpose of the pop-up was more about book promotion, but the intent is to have a barbecue restaurant in LA, correct?

APL: Definitely. I’m very close. I’m trying to do this 10,000 square foot thing. I’d like to do a butcher shop and a steak place and a pure barbecue place. It’s just taking a long time to do something bespoke and not have to fit into a place. No offense against Ole Hickory but I don’t want to do set-it-and-forget-it cooking. I want to do craft barbecue, barbecue that’s pure.