What you know about the history of smoked brisket in Texas is probably wrong. People have been eating brisket since the first pits were dug in the earth, but only by a sort of default: it was standard practice to cook whole animals for the big community celebrations, which means people ate that cut of meat as part of a smoked-meat meal where all the various cuts were served. These days, smoked brisket on its own is widely considered the king of the Texas barbecue menu, but it hasn’t always been that way, and contrary to some bold claims by certain barbecue joints, it didn’t start with Central Texas meat markets.

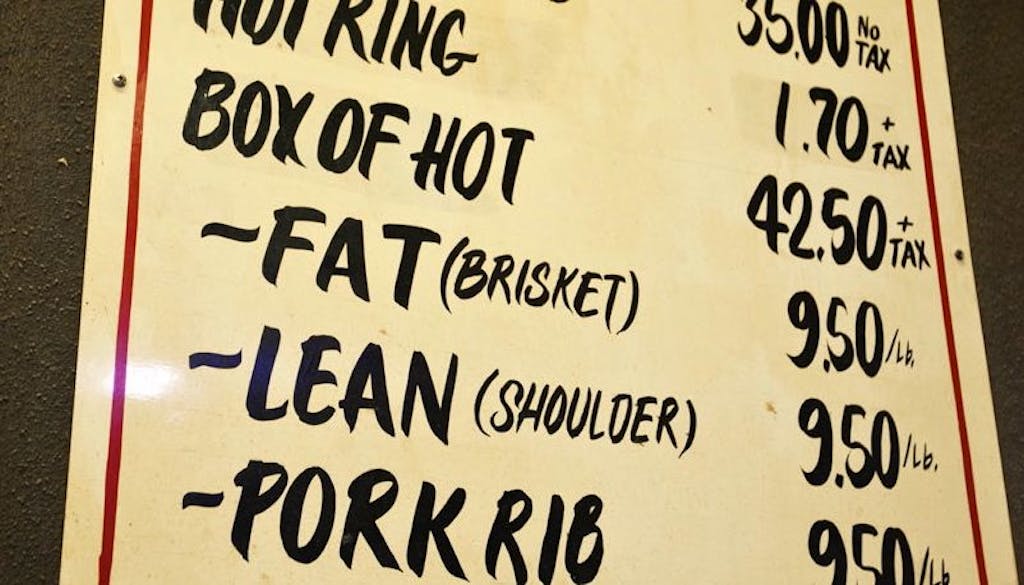

Black’s BBQ in Lockhart credits themselves with being the first to use briskets exclusively on their barbecue menu. That was in the late fifties. By the sixties the beef purveyor IBP was shipping individual beef cuts in boxes, and the tradition of working with half carcasses saw a swift decline. It wasn’t until then that most of the barbecue joints around the state started adopting this inexpensive cut of meat. Joe Capello of City Market in Luling remembers when they would separate the forequarter away from the carcasses. The rib section and the sirloin would make it into the raw meat cases while the entirety of the front of the animal–the cross-cut chuck–would be separated and smoked. Back in those days you didn’t ask for brisket or clod at these Central Texas meat markets. As Capello explains, “Customers would just come in and ask for beef. If they wanted it fatty we’d give them the brisket. If they wanted lean then we’d do the shoulder clod.” The menu at Smitty’s Market in Lockhart is reminder of those options. “Lean” means shoulder clod and “Fat” means brisket.

Allen Prine up in Wichita Falls remembers it the same way. His grandfather Harold Prine Sr. opened Prine’s Market in 1925. They sold hams and beef, but not specifically brisket. They would just get the whole forequarter and butcher it themselves. “We’d cut these big these big 110-pound pieces into about eleven different shaped pieces. We cooked them all exactly like we do the briskets now.” He doesn’t remember serving brisket on its own until about thirty years ago when they started ordering cryovaced ones. “It’s always been that way since.”

Two things came together to create the brisket we know today. The Institutional Meat Purchase Specifications (IMPS) for beef were first published in 1958, and boxed beef came onto the market in 1965. IMPS was a guide used in contracts for large meat purchases to ensure the buyer (read: at first, primarily the military) could get a predictable product when they ordered a thousand chuck rolls. These same specs are followed by meat packing plants for retail cuts, and customers as small as mom-and-pop barbecue joints order their meat based on IMPS. Whether they know it or not, that whole boneless brisket is really IMPS item #120. I wanted to know how much differently cattle were butchered before IMPS. Did briskets in the twenties look like they do today? I needed an expert.

Steve Olson is a cattle rancher in upstate New York, but he worked for USDA for decades. When he started his government job they needed someone to overhaul IMPS in 1983, and as he puts it “I was a lousy writer” and the specs didn’t require any flowery language. He took to the task. Today you can find him and his Jersey accent starring in the meat cutting videos provided by NAMP. I asked him to surmise how Texas meat markets might have cut a brisket from the forequarter. He said the location of the cross cut used today that creates the top edge of the brisket is probably where they cut it back then too. The end of the sternum where the brisket cut begins is what he called a “landmark” for meat cutters back before IMPS. But it would probably have been smoked with the bones still attached. It wasn’t until the mid-seventies when boneless briskets became standard. Steve traveled with some cryovac reps then as “they were trying to get the industry to make everything boneless so the cryovac wouldn’t leak.” Now you can’t find a bone-in brisket.

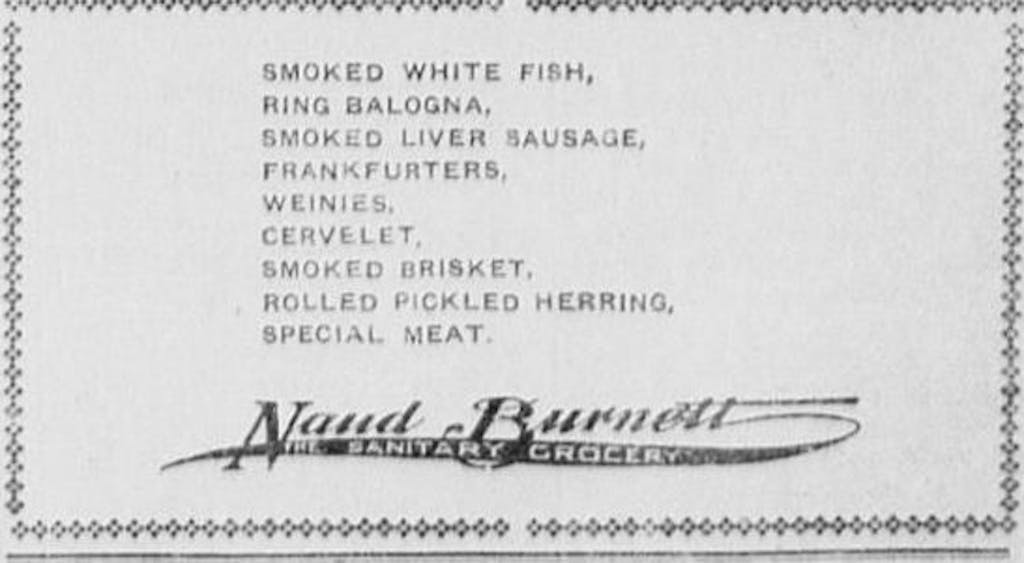

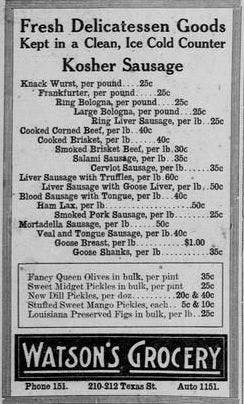

I’m not sure what the briskets looked like back in the early twentieth century, but the earliest mention I can find of smoked brisket isn’t from the fifties, and it wasn’t at a barbecue joint. Rather it is from newspaper advertisements from two grocery stores in 1910. Naud Burnett in Greenville and Watson’s Grocery in El Paso were both serving smoked brisket from their deli counter along with other traditionally Jewish food items like smoked white fish and Kosher sausage. I’m not certain of the religion of these grocers, but their menu is geared toward a Jewish clientele.

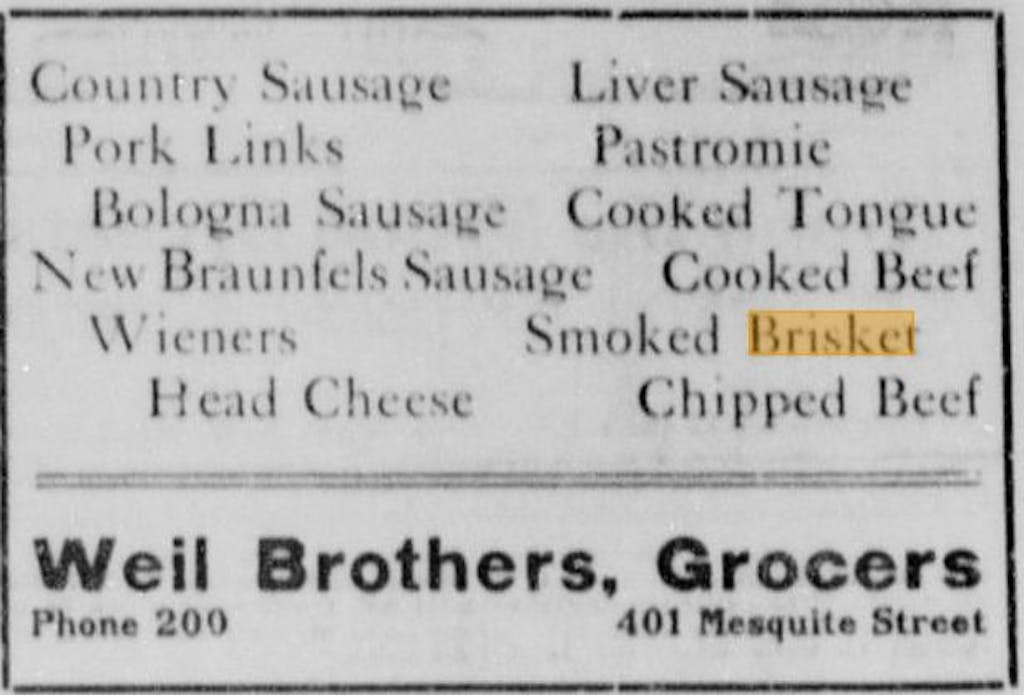

A few years later in 1916 the Weil Brothers in Corpus Christi advertised their smoked brisket. The store was owned by Alex and Moise Weil. Their father Charles Weil was a Jew who emigrated to Texas from Alsace, France, in 1867. Pastrami (cured and smoked brisket) is a common item on Jewish menus, but in their store they sold pastrami (pastromie in the ad) along with smoked brisket. It probably wasn’t served hot on butcher paper like the Central Texas meat markets, but those meat markets wouldn’t be listing brisket on their menu for another forty years.

If you know the requirements of Kosher food, it makes sense that Jewish immigrants would be the first ones to smoke specifically brisket in the States. The hind quarter of beef isn’t Kosher unless the sciatic nerve is removed, and that is rarely done by butchers. That leaves the forequarter including the brisket, which is revered as the cut of meat to enjoy for Passover. Evidently, it was also popular enough for the smoked version to make it into Jewish grocery stores in Texas long before it became the darling of our barbecue joints.

- More About:

- Brisket