What is your greatest fear? It’s a simple question you’re rarely faced with outside of an interview setting. We just got a new editor in chief (congrats to Tim Taliaferro) at Texas Monthly, so I may have to reinterview for this barbecue editor gig. You never know how these things go. But if I’m asked about my greatest fear, it’s not dying in a fiery crash on I-35 during one of my many trips around the state. My greatest fear is smaller than a fingernail. It is Amblyomma americium, the lone star tick.

No, it’s not Lyme disease that scares me. There are treatments for that. But an allergy to alpha-gal? That shakes me to the core. There’s no cure, and it would literally ruin my life. Alpha-gal is the nickname given to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. It’s a sugar found in the blood of non-primate mammals, all the furry animals that aren’t apes, chimps, or humans. Scientists have determined that a bite from the lone star tick (so named for the lone “star” on the backs of mature females) can lead to an allergy to alpha-gal, and along with it, an allergy to any meat that contains it, like beef, pork, lamb, you see where we’re going here. Being allergic to alpha-gal essentially means being allergic to Texas barbecue.

I first heard of the red meat allergy a couple years back, but I learned details from a recent episode of Radiolab that were particularly alarming. Hives, fainting, and severe intestinal distress are the gifts of the alpha-gal allergy. Reactions can be as severe as those from a nut allergy including anaphylaxis, made worse by a cruel delay in onset. It can take three or more hours for the allergic reaction to take hold, which means it can literally become a part of nightmares if dinner for an unsuspecting victim includes red meat. Thomas Platts-Mills, the scientist who helped make the connection between the lone star tick and the meat allergy, suffers from the alpha-gal allergy. He recounted his first reaction with Radiolab. “I was taken out to dinner, and the lamb chops were particularly delicious, and the French wine was delicious,” he said. “Six hours later I woke up covered in hives.” This was all after a hike in the Blue Ridge Mountains which he encountered “two hundred seed ticks.”

Platts-Mills told Radiolab he first heard stories about a meat allergy in 2004 and initially dismissed them. “Adults don’t become allergic to something they’ve eaten for forty years out of the blue, and certainly not red meat,” he said. Then Platts-Mills was asked by a drug company to figure out why cancer patents taking the new drug cetuximab were having allergic reactions, and he eventually zeroed in on alpha-gal as the culprit. That led to Platts-Mills and Scott Commins publishing a study in 2011 in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Their conclusion was, “The results presented here provide evidence that tick bites are a cause, possibly the only cause, of IgE specific for alpha-gal in this area of the United States.” The New Yorker put the cause into layman’s terms in a 2014 article on the allergy. “[T]he saliva of lone-star ticks sensitizes humans’ immune systems to alpha-gal, triggering the release of histamines when red meat is ingested.”

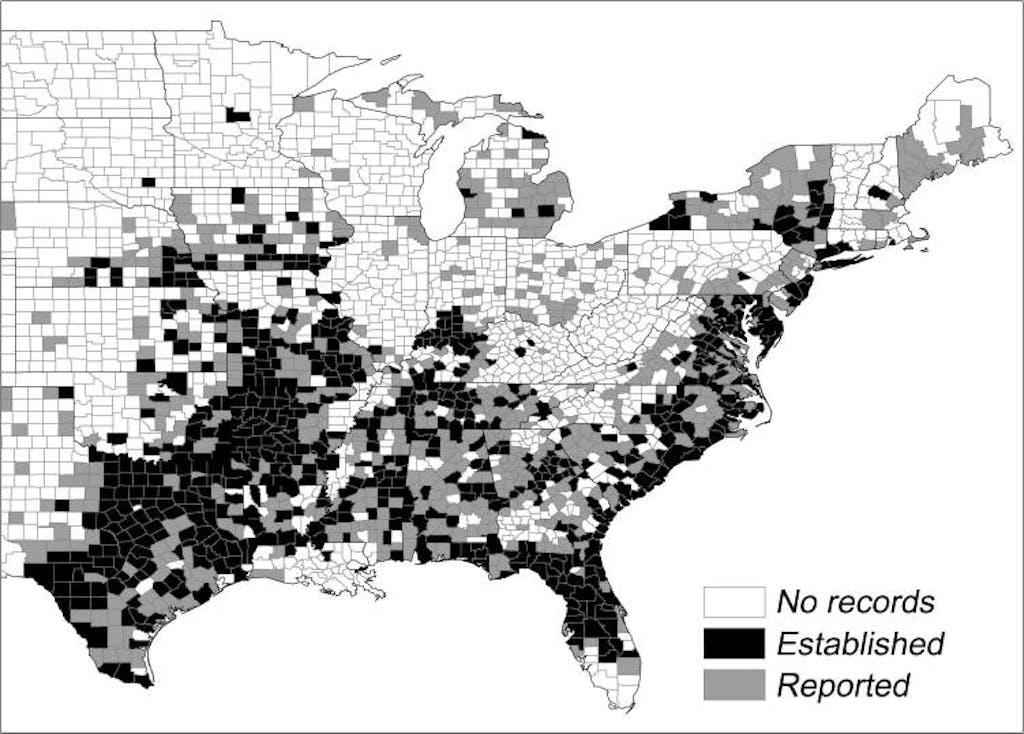

The car was loaded with hiking gear as I listened to the alpha-gal podcast episode. My family and I were headed to Big Bend National Park, noted home of mountain lions and black bears, but I somehow feared a possible encounter with those predators less than with a lone star tick. I dressed in long pants, long socks, and long sleeves, watching the path ahead of me for tick nests rather than snakes. We finished one hike in the dark with headlamps to guide us, and I couldn’t give a flip about a coyote encounter. Thankfully, I came away unscathed, and once back into civilization I learned I was never in much danger. The habitat for the lone star tick stretches from New York, down through the south and into Texas, but reaches no further west than Del Rio, at least not for now.

The CDC notes that the “distribution, range and abundance of the lone star tick have increased over the past 20-30 years.” That 2011 study from Platts-Mills also predicted that “that populations of both deer and ticks will continue to increase their range, particularly in suburban areas. Thus the number of Americans exposed to these ticks and their larval forms will, in all probability, continue to increase.”

Commins, the other scientist involved in the 2011 tick study, told Allergic Living that there are 3,500 documented reports of red meat allergies in the U.S., and that the number could be even higher. He notes that cases of the allergy are rapidly increasing, but that may be due to doctors just now understanding this new meat allergy. According to Commins’s Twitter account, UNC will host a symposium on alpha-gal next April. Hopefully it fosters further study into a cure. Until then I’ll continue wearing jeans and long sleeves, even while hiking the Dallas pavement.

Amy Pearl, a former meat lover, was the focus of the Radiolab episode. She suffers from the alpha-gal allergy, and though the thought of a hot dog still makes her mouth water, she admits, that the “tick is helping me evolve into a better human” by eating less meat. I applaud her ability to accept her affliction, but I love brisket too much to want to join her. Those who already suffer from the alpha-gal allergy can still eat poultry and seafood, so there’s still room for you at the Texas barbecue table (see here and here). But I’m hoping I never have to stick to the smoked chicken and turkey beat.