Pastrami is to New York City like smoked brisket is to Lockhart, Texas: they are the signature smoked meats of their respective cities, and both lay claim to being the originator. Black’s BBQ has said in the past that they were the first to put brisket on the menu in Texas. They were certainly on the leading edge of the menu innovation, but proving that is a tougher task. As for the first smoked pastrami, a highly regarded New York food writer questions whether the innovation was really born in New York City. Maybe pastrami as we know it started in Texas.

In his new book New York in a Dozen Dishes (to be released next Tuesday, 5/19), Eater columnist Robert Sietsema* looks back on the history of the cities famous dishes. I received an advance copy to provide a blurb for the book, and chapter by chapter Sietsema covers iconic menu items like pizza, Manhattan clam chowder, barbecued brisket (guess where they got that idea), and pastrami. He pieces together each dish’s history and describes how New York either created them or made each one their own.

The pastrami chapter hums along predictably enough to those who’ve read up on cured and smoked beef. Romanian Jews brought their native pastrama (a derivation of the Turkish basturma) to New York City in the late nineteenth century. Pastrama was made by curing large cuts of beef, then drying it or cold smoking it. David Sax described it in his book Save the Deli. “In Romania, pastrami is not so much a food as a method of preparation that involves a heavy dry rub of salt and spices to cure and season the meat, and later smoking to cook it fully.” The finished product was dry and thinly sliced. It was more like bresaola or even beef jerky than the juicy pastrami we eat today.

An export log from Braila, Romania to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) from Hunt’s Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review in 1852 listed it as “pastorma, or jerk beef.” The point being, not matter how it was spelled, it wasn’t the smoked beef we’re used to today. Smoking and steaming the cured beef into something resembling Texas smoked brisket didn’t happen until the dish was altered in the U.S.

David Sax also wrote an article for Saveur magazine describing modern pastrami. “Making pastrami—from either the brisket or the navel, both tough, sinewy, cuts of beef—involves a series of processes: salting; rubbing with a mix of garlic, pepper, coriander, mustard seed, and sugar (among other seasonings); and smoking.” The famous Katz’s Delicatessen in New York uses beef navel while most pastrami you’ll find in Texas (or Montreal for that matter) is made from beef brisket. For a time beef shoulder clod was popular. That’s what Simon David in Dallas used in the forties and in 1938, a National Provisioner recipe for pastrami in Sausage and Meat Specialties stated that “shoulder clods of kosher cattle are generally used.”

Sietsema and others generally give credit for creating modern smoked pastrami to Katz’s. From Sietsema, “[T]he modern form of pastrami may well have been invented by the German-Jewish deli men like those at Katz’s, altering it substantially from its European form, though perhaps using some of the same spices.” Katz’s opened in 1888, but don’t let that early date be too persuasive. It’s likely that Katz’s started off selling franks and salami. As Sax puts it in Save the Deli when discussing the early era of New York Delicatessens, “in the beginning, it was just a whole lot of tube steak.”

Nobody knows precisely when the pastrami entered the market, or when the transformation from jerky to juicy happened. New York wasn’t exactly known for smoking meat in the 1880’s, which is what leads to Sietsema (who is originally from Dallas) to make a bombshell statement toward the end of his pastrami chapter. “It’s fun to think that maybe pastrami as we know it – corned beef rubbed with spices and smoked – might have originated in Texas…”

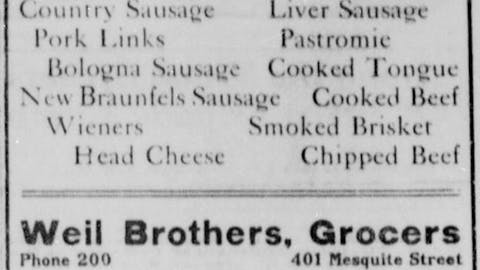

He was using some of my early smoked brisket research to arrive at the idea. Weil Brothers Grocers advertised smoked brisket along with “pastromie” in a Corpus Christi newspaper in 1916. The store was opened in 1911 by Alex and Moise Weil, whose father was Charles Weil, a Jew who emigrated to Texas from Alsace, France, in 1867. In 1915 they began construction on an enormous warehouse. The Corpus Christi newspaper called it “the largest structure for the purpose in South Texas.” The brothers installed a deli in May 1916 when they started selling smoke halibut, smoked brisket, and pastrami. That sparked Sietsema’s theory that maybe pastrami first became something we’d recognize today in Texas smoker.

New York native Patricia Volk disagrees with both theories, and instead credits her great-grandfather as the father of modern pastrami in her book Stuffed. “Sussman Volk brought pastrami to the New World,” she proclaims. He began selling pastrami in 1887 ( a year before Katz’s opened, but a year after Southside Market opened a barbecue joint in Elgin) after receiving a recipe from a Romanian friend who made a bargain with Volk. “‘If you store my trunk, I will give you the recipe for pastrami.'” There’s no record of this, but it makes for a good legend. Even if the date and the story are true, it’s doubtful that the conversation went like that at all because the word “pastrami” as it is spelled today is a newer invention.

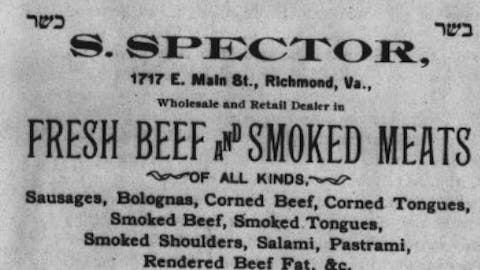

One of the earliest mentions I could find of “pastrami” was printed in the Fort Worth Star Telegram in 1926 in what appears to be a syndicated column entitled New York Day by Day. O. O. McIntyre described a walk down Delancey Street in Manhattan noting “The Kosher shop windows display pastrami, corned beef, salami, dill pickles, duck, and stuffed goose.” But the first record I could find of the word in print was in The Jewish South newspaper out of Richmond, Virginia where S. Spector advertised pastrami for sale along with smoked beef, smoked tongue, smoked shoulder, and salami. (Salami and pastrami traveled in the same circles leading to the widely accepted etymological theory** is that the popularity of salami caused pastrama to become pastrami). Maybe we’re all wrong, and Richmond is really the father of pastrami.

New York, Virginia, and Texas were on board with an early love for pastrami, but it wasn’t well known across the country for several decades. Chicago was once the hub of American beef packing, but a question from a customer stumped the authors of Secrets of Meat Curing and Sausage Making published by Chicago-based B. Heller & Co. in 1916. “Can you furnish me with a recipe for making (Postromer) Peppered Beef?” asked the customer. The answer is comical. “We do not clearly understand your question. If you mean cured Briskets that are covered with red pepper, or Paprika Compound, and then smoked, you can proceed as follows…”

Postromer wasn’t the most common spelling, but the answer didn’t even mention a term for pastrami. The Weil brothers brought us “pastromie,” but that was far from the only derivation. Before the 1930’s there were countless terms like “spiced pastromer” at Sonnemtheil’s in Dallas in 1908, or “pastroma” as advertised in Dallas, Greenville, and Fort Worth between 1909 and 1911. There was also pastrame, pestrame, pastromi, and pasturma. All of these variations make it harder to track down an origination point. Even if we did find the first restaurant that served it, it’s hard to tell whether or not is was smoked like today’s pastrami. Even in 1920, Hygrade Provisions Company in Brooklyn applied for a trademark patent, and they listed “Smoked Pastroma” of several varieties as part of their product line. Evidently the modifier “smoked” was still required.

Texas and smoked meat have a long history, and before this research project I didn’t realize how early we developed a love for pastrami in the Lone Star State. Variations of it were advertised in Dallas, San Antonio, Corpus Christi, El Paso, and even Wichita Falls before 1920. Maybe Sietsema’s theory isn’t so far-fetched, but I’d bet plenty of New Yorkers would be willing to argue.

* Robert Sietsema and I share the same literary agent.

** For a startlingly enormous study on the etymology of “pastrami” peruse Studies in Etymology and Etiology by David L. Gold.