After thousands of barbecue meals, I’ve never been struck ill by smoked meat. Maybe it’s the long cooking time, or the preservative qualities provided by a layer of wood smoke, or maybe I’ve just been lucky. Either way, I put that streak to the test over the weekend.

“How long can you keep a brisket in the fridge before it goes bad,” a friend asked me one morning. It was April of last year, and Coach Bill (he coaches my daughter’s soccer team), still had a couple briskets in the fridge that he found on sale over Christmas. He had just read about Texas A&M’s McKenzie Project, where they were planning to taste-test briskets that had gone through prolonged wet-aging, but 35 days was their max. Bill was looking at four months. I encouraged him to proceed with caution. It took several more months, and an impassioned plea from his wife to clear out their fridge, for him to rope me into the experiment. In September, he smoked one of his Christmas briskets.

Nine months is a long time to age beef, especially wet-aged beef. All beef used to be dry-aged for some period of time. Before the introduction of cryovac, where individual cuts of beef are sealed in a thick plastic, in the late sixties, all meat was hung or shelved in a cooler where it dry-aged. The practice is still done by meat suppliers and at high end steakhouses like Carnevino in Las Vegas or Knife in Dallas where you can order a steak that’s been dry-aged for 240 days, and even 420 days on some occasions. The length of wet-aging generally tops out a few weeks, although I had great success with wet-aging a prime rib for a month before smoking it for Christmas last year.

Dry-aged brisket is uncommon, but they offer a 21-day-dry-aged, smoked brisket at Killen’s Barbecue in Pearland. As for wet-aging briskets, some pitmasters swear that leaving them in their cooler for a couple weeks improves the flavor and tenderness. At Franklin Barbecue, they wet-age their briskets between 14 and 40 days. “Around forty days, things get a little funny,” Franklin told me, but there hasn’t been the same level of intrigue on really prolonged wet-aging as there has been for pricey, dry-aged steaks.

Storing a brisket for nine months is crazy, and waiting a year is even more demented, but Bill had two Christmas briskets at home, and he’d only smoked one. We agreed to wait the full year before smoking the other one, but I wanted to talk with Dr. Savell at Texas A&M’s Rosenthal Meat Center before proceeding. He said to look out for obvious signs like a green color in the meat or mold growth, and to make sure the bag hadn’t puffed up as a result of bacteria growth. Once I opened the bag, he expected it would smell rancid from lipid oxidation, essentially rotten fat. Fat goes rancid through oxidation. Storing in cryovac keeps out the oxygen, and prevents spoilage, so the Yearling (as I had come to start calling it) might be in the clear. Still, Savell couldn’t really tell me what to expect because, as he said, “Nobody would be wet-aging something that long.”

In 2013, when Andrew Zimmern toured the Certified Angus Beef (CAB) facility in Ohio on his Bizarre Foods show, they fed him some 50-day-wet-aged steak. Diana Clark, a meat scientist at CAB told me they’ve smoked briskets that had been wet-aged up to 90 days. “It still eats really well,” she assured me, despite the slightly sour flavor from lactic acid buildup.

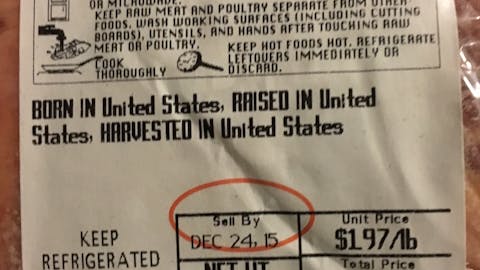

The consensus was in. Nobody wet-ages their meat for a year, and those in the industry would be hesitant to eat it. Bill and I might become the first people to eat a smoked brisket that had been wet-aged for over a year. So, 393 days past the “sell-by” date, I opened the package around midnight in my garage. It didn’t smell rancid. I opened a fresh brisket next to it to compare. The new one had a brighter mineral odor that you’d expect in fresh beef. I’ve smelled rancid beef. It makes one immediately recoil in disgust, but the Yearling smelled downright fine. Most importantly, it smelled edible. After some salt and pepper, it went on the smoker.

Diana Clark and chef Michael Ollier at CAB were both stunned that it didn’t smell rank. “That’s pretty phenomenal,” Clark said. “That’s how sanitary it was. No bacteria growth happened for one year.” She credited the packer. It was an IBP brisket with establishment number 278 on the package meaning it had been packaged by Tyson Fresh Meat in Holcomb, Kansas. Nice work, Tyson.

The Yearling smoked at the same rate as the similarly-sized Choice brisket. I expect the fat might render differently, but the surface texture was also similar. After many hours in the smoker, and a long rest, it was time for the moment of truth.

With one whole conventional smoked brisket coming off the smoker, I had to invite some friends over. I warned them about the Yearling, but some still partook. We began with leans slices from both as a comparison. The surface fat held onto to the smoke and seasoning so well, it was hard to tell any real difference. The meat was another story. The beef on the Yearling had subtle livery notes. It was a mineral flavor that I’d also describe as serumy, a word I learned from the “lexicon of meat flavor descriptors” found in a study on aged beef. It wasn’t great, but good enough that I took more than one bite.

The trouble started once we got further into the brisket. The fat layer in between the point and the flat had turned spongy. It still smelled okay, but was sour and bitter. A small bite provided the same reaction as a shot of Malört I’d had in Chicago. And as with Malört, the only thing to get the taste out of my mouth was a shot of whiskey. I didn’t go back in for another bite, and neither did anyone else.

After the cook, I asked Dr. Savell, as a doctor of meat, if he would have eaten it. “There probably would have been some hesitancy,” but, he politely added, “I would not have taken a big mouthful.” Of the sourness in the middle seam fat, he said “There are a lot of air pockets in there. More air may have been captured in there a year ago.” The air could have cause oxidation in the seam fat, while leaving the rest of the brisket unharmed. Diana Clark noted that seam fat “is more unstable” than surface fat on a brisket. There are more unsaturated fat (which are more prone to oxidation) in the internal fat than in the more saturated surface (subcutaneous) fat.

The prolonged wet-aging didn’t provide much benefit for flavor, but thanks to enzymatic breakdown, the Yearling was more tender than any other Select grade brisket I’ve eaten. In On Food and Cooking, Harold McGee explains how enzymes get to work in beef once it begins aging:

Enzymes called calpains mainly weaken the supporting proteins that hold the contracting filaments in place. Others called cathepsins break apart a variety of proteins, including the contracting filaments and the supporting molecules. The cathepsins also weaken the collagen in connective tissue, by breaking some of the strong cross-links between mature collagen fibers. This has two important effects: it causes more collagen to dissolve into gelatin during cooking, thus making the meat more tender and succulent; and it reduces the squeezing pressure that the connective tissue exerts during heating, which means that the meat loses less moisture during cooking.

Basically, the aging process makes beef more tender, and more aging means more tenderness. Select grade briskets are tougher than their Choice and Prime counterparts, which is why so many pitmaster are switching away from them. Dr. Savell pointed out that 30 percent of beef is Select grade, which means a glut of Select briskets on the market. Tenderization through prolonged wet-aging might be a way to make Select briskets more valuable to pitmasters. I’m looking forward to more study from Texas A&M and CAB on the subject, but I can tell them from experience, a year of wet-aging might be a little much.

- More About:

- Brisket