The director of Foodways Texas, Marvin Bendele, asked me to come and lead a couple of panel discussions at the organization’s annual Camp Brisket, held last weekend at the Rosenthal Meat Center on Texas A&M’s campus. And even though I was presented as an expert to talk about the history of brisket, I found there was still, ahem, a lot to chew over and learn. As someone who feels as though he knows most everything there is to know about a beef carcass, a conversation with Professors Jeff Savell and Davey Griffin, the masters of ceremony, quickly put me in my place. So I share with you five meaningful things that I learned while at Camp Brisket.

1. Beef grades only matter to a point

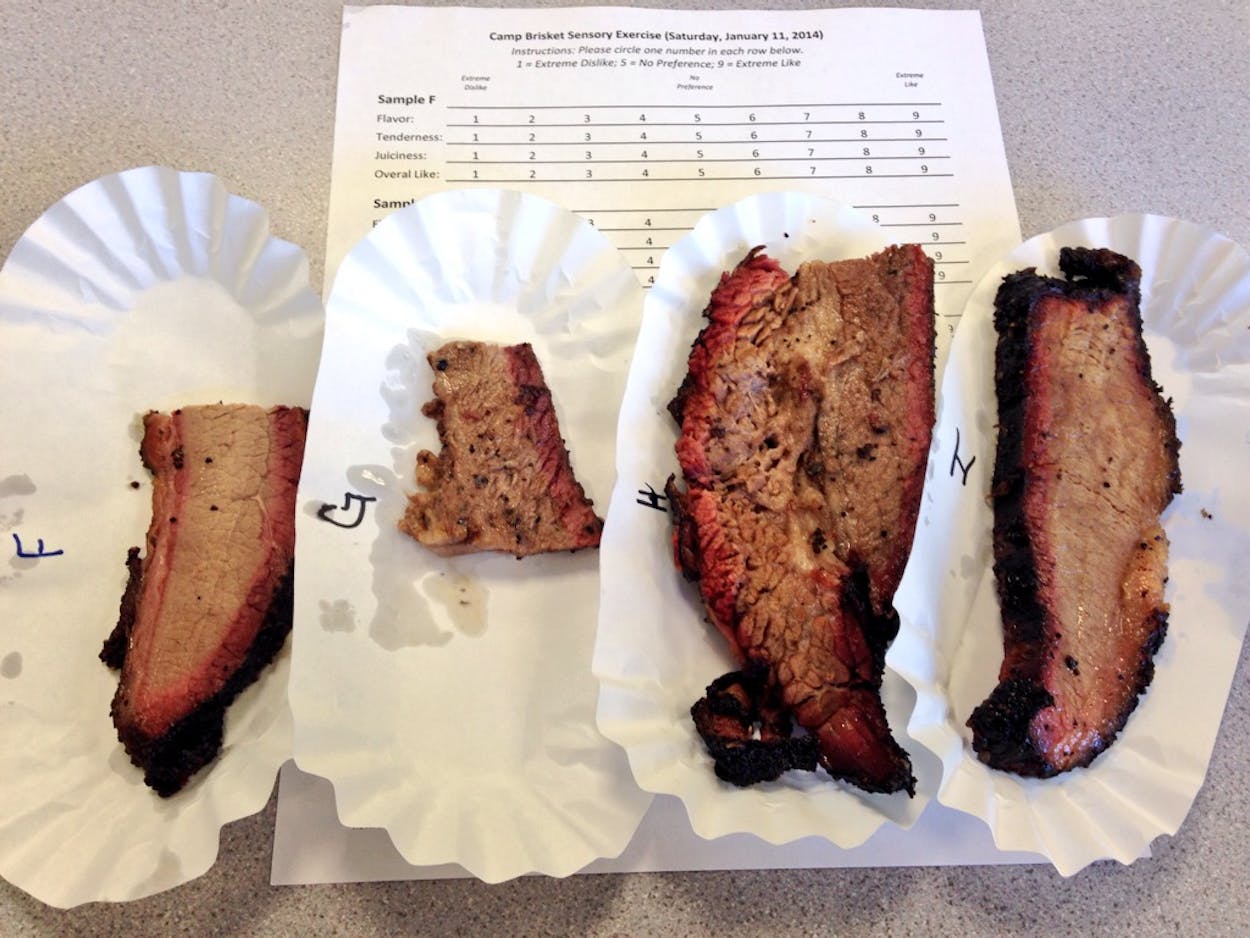

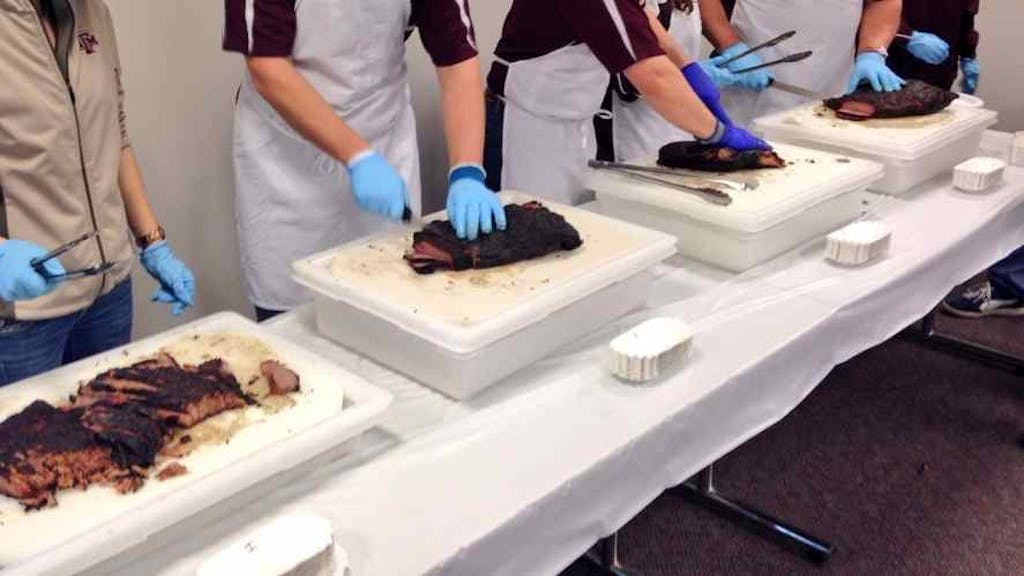

Five briskets, all of different grades, were smoked by the Texas A&M students and staff. All were seasoned (too heavily) with the same mix of salt and pepper, and smoked with the same wood for the same time and temperature in the same Southern Pride rotisserie. In the mix was, from least to most expensive, Select, the low third of Choice, high Choice (Certified Angus Beef or CAB), Prime, and Wagyu. I took pieces from the end of a slice from the flat of each one to get as close to the same portion as possible.

Select and low Choice were pretty easy to spot. The grain of the meat was tighter and the slices were drier. One would expect the Wagyu, which runs for double the price of even Prime grade per pound, to outshine all of the competition. When it came to the blind tasting it was hard to distinguish. CAB, Prime, and Wagyu were all very similar. I actually selected the Prime as being the pricey Wagyu. While there was slight variation between the three (they were three different animals, after all), they were all good eating briskets. The point is that it’s tough to advocate paying the high price for Wagyu for a cut like brisket that’s already so well marbled. The gap in flavor and moisture between Prime and CAB was also minuscule, something to consider when you’re looking at that price difference of about 25 cents per pound.

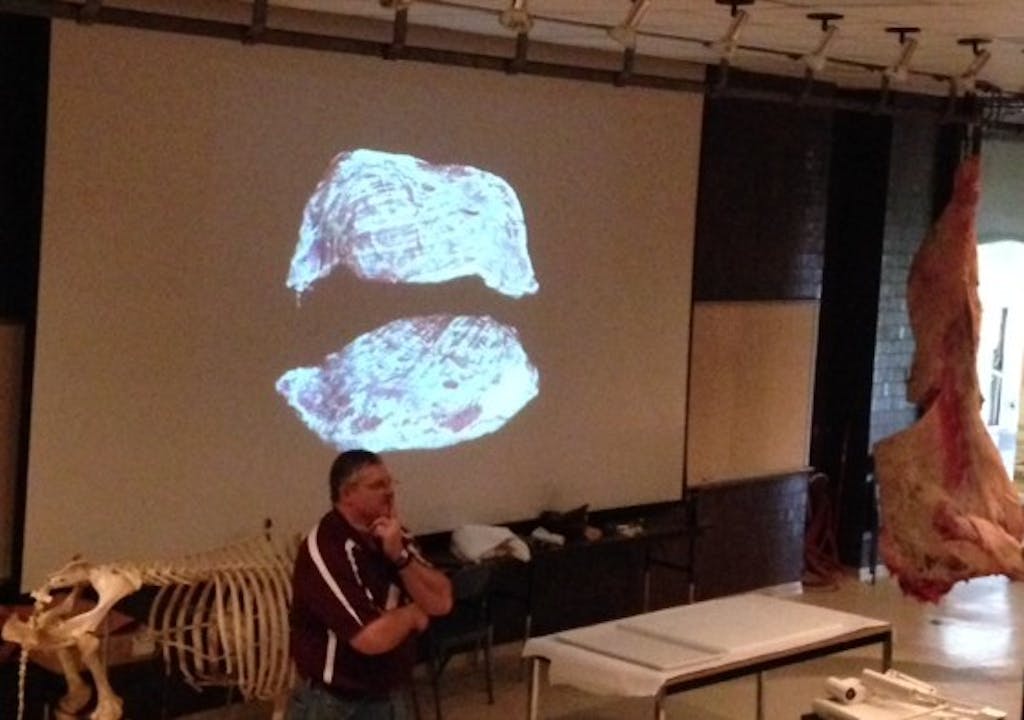

2. What You Should Know About the “Whole Deep Pectoral Muscle”

The system used to butcher a beef carcass in the US follows a rigid process. Rather than just using the natural seams between muscles, a chart of subprimals is involved. The forequarter of the animal is separated from the rest of the animal by a cut between the fifth and sixth ribs. The thin, exposed edge of a brisket flat looks like a muscle cross-section because it is one. It’s only a portion of what is referred to as the Whole Deep Pectoral Muscle. You won’t find this cut listed on any order form from a meat supplier because that whole muscle isn’t a marketed cut of beef. It is divided into three separate cuts that all fetch a different price.

On the other side of rib number six is the continuation of that muscle. This is the beef navel. It’s a cheap cut that is commonly used for pastrami, and was used as such long before brisket became popular for pastrami.

The Whole Deep Pectoral Muscle is further separated from the brisket by a cut along the top. Above that cut line you’ll find a less familiar cut called Beef Chuck, Square Cut, Pectoral Meat (NAMP Item 115D). While a whole, boneless beef brisket (NAMP Item 120) is the more familiar cut, the pectoral meat actually fetches a higher price. As of this week, the Choice version was selling on the wholesale market for $2.82 per pound compared to brisket’s $2.21 price tag.

All of this rather long-winded (and super inside-baseball) explanation is to help understand the market forces that create long, skinny briskets. As Davey Griffin explains, the goal of a beef processor is to cut more valuable meat away from less valuable meat. While separating the brisket from the carcass, a processor can cheat a bit by separating the brisket and the pectoral meat a little lower on the animal giving more weight to the more expensive pectoral cut. To ensure consistent weights on their brisket they’ll just steal a bit of the cheap navel meat from across that sixth rib to make up the difference. Pitmasters hate these long skinny briskets because they’re too long for the shelves of a rotisserie, and the meat at the end of the flat is so thin that it becomes jerky by the time the thick point is done smoking. Because of this most folks will just trim it off right at the start which creates wasted beef and hurts a barbecue joint’s already thin bottom line. At least with this explanation a pitmaster will know what to complain about to their supplier if those skinny briskets become commonplace.

3. Freeze Fast. Thaw Slowly.

When meat, vegetables, or fruit are frozen, the abundant water within freezes into ice crystals. These ice crystals irreversibly damage the fibers within those foods, which is why fresh meat is more desirable than previously frozen. If you’ve ever tried to extend the life of strawberries or a bell pepper by placing it in your home freezer, then you know the problem. After they thaw, the flesh turns to a watery mush. The same thing sort of happens in muscle fibers.

One way to counteract this is to flash-freeze those items. Freezing items more quickly results in the formation of much smaller ice crystals, and those smaller crystals do less damage to meat. Not that many barbecue joints are using frozen meat instead of fresh in the smokers, but many around the state now ship their barbecue. The best way to ship a brisket to ensure that it remains cold through the mail is to freeze it first. Flash freezing will keep that meat from turning to mush when the customer reheats it.

The customer can also help themselves in this situation. Thaw slowly. Putting that slab of nearly frozen brisket on the counter will cause shock to the muscle fiber. Putting it in the fridge will thaw it more gently so hopefully it will have some integrity once you reheat it.

4. Wood Matters

Four major hardwoods are used for barbecue in Texas – oak, hickory, pecan, and mesquite. When asked for a preference, I generally tell people that mesquite smoke can be harsh, but it’s hard to distinguish from the other three. After Camp Brisket, I know that’s not entirely correct.

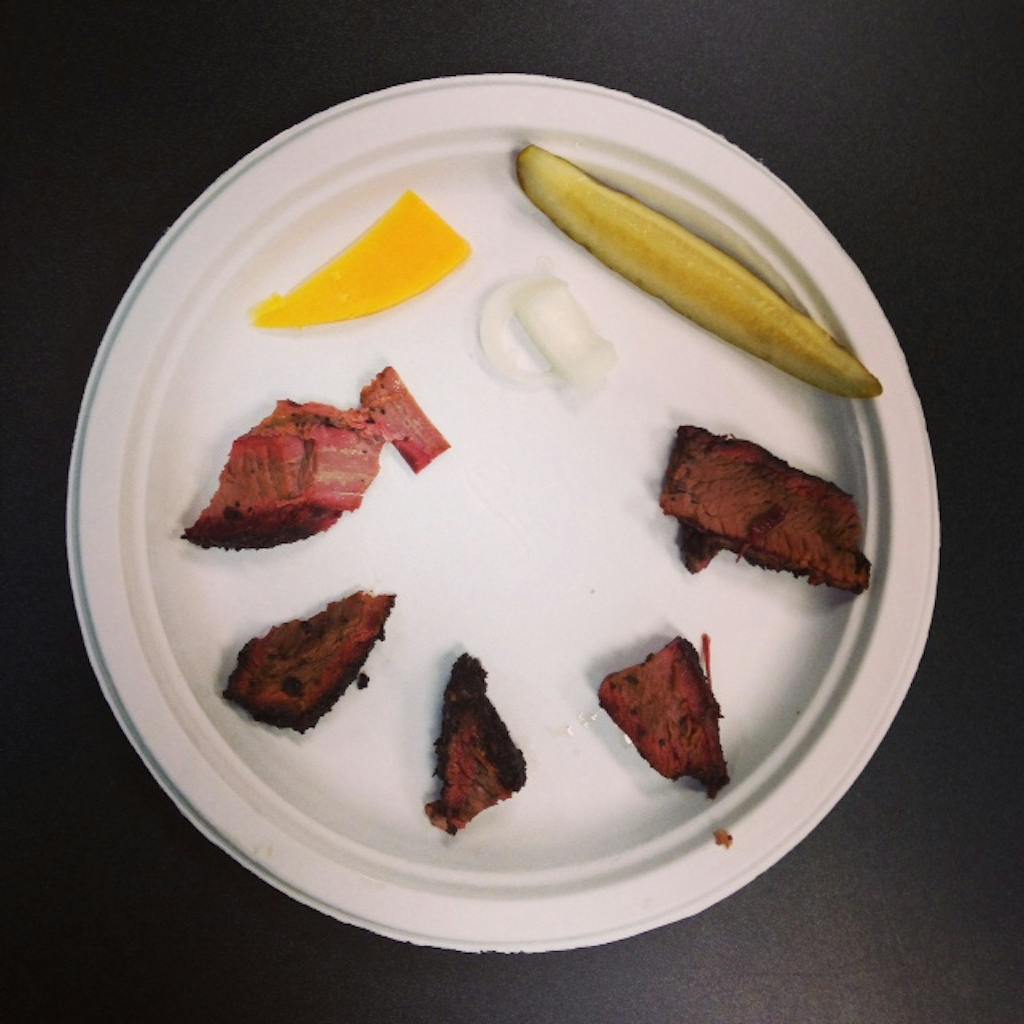

For lunch on day two, briskets were smoked over all four of those hardwoods. Unlike the day before where the different grades of meat were cooked under the same conditions, there were four separate smokers involved for this test. It’s hard to account for the different variables in each smoking chamber, but the final result from all who filled out their “Sensory Exercise” form was that hickory was the preferred wood. That might have been because that brisket was well cooked while the pecan-smoked brisket was a ways from being done, but one thing was obvious after tasting them side by side: the flavor from oak is distinct from the flavor of pecan, hickory, and mesquite. Mesquite was the easily identifiable outlier, but the others were still unique. I can’t say that I preferred one by any wide margin, but I certainly didn’t dislike any of them. It was a tray full of smoked brisket after all.

5. Franklin Barbecue uses nearly every “all-natural” brisket that Creekstone can process.

Hormones, antibiotics, and growth promoters are all commonly fed to conventionally-raised beef as they are fattened in feedlots. If you’re eating barbecue in Texas, chances are that’s what you’re consuming. Boxes of IBP (short for Iowa Beef Processors, but now owned by Tyson) briskets are ubiquitous, but a few barbecue joints prefer a different route. Franklin Barbecue is one of them. They purchase briskets from Creekstone Farms in southern Kansas that are free of hormones, antibiotics and growth promoting drugs (referred to as “all-natural” from here on out). This is an ethical choice according to Aaron Franklin who pays a nice premium for that beef. The final product is also pretty good (hello, best in Texas the world), so why don’t more pitmasters make that same choice?

Besides price being the major deterrent, another thing to consider is supply. There simply aren’t enough “all natural” briskets to go around. Aaron Franklin attended Camp Brisket where he talked about the challenge of getting briskets. He can’t be picky these days because he’s getting nearly every all-natural brisket that Creekstone can produce. This week that was four hundred briskets, or two hundred head of cattle. If another barbecue joint of similar size wanted to use these same all-natural briskets, they would have to find another supplier. According to Franklin, who has done some shopping around, there isn’t another single producer who can supply that many all-natural briskets every month. While most choose to cook conventional briskets based on cost alone, it must be understood that it doesn’t always come down to price. There are only so many cattle out there, and only a small percentage can be considered all-natural.

It’s a humbling thing to go into an event where you’re supposed to be the expert and realize how much there still is to learn. Barbecue and beef in Texas are such rich subjects, I’m glad there are teachers like Drs. Savell and Griffin who are willing to teach us barbecue fiends and organizations like Foodways Texas to bring us all together.

- More About:

- Brisket