Nick and Jennifer Pencis were itching to reopen their two restaurants in Tyler, Stanley’s Famous Pit Bar-B-Q and Roast Social Kitchen. Even before the statewide restaurant restrictions were put into place, they switched to curbside service, but it was a hectic way to run a barbecue joint. Because they were operating on a third of their usual revenue, the couple announced what they thought would be a two-week closure for Stanley’s beginning on March 20 (they closed Roast on March 17). Last week, they finally decided it was time to fire up the pits once again at Stanley’s, which opened for curbside service Thursday.

The Pencises contacted their laid-off employees and gathered to deep-clean the restaurant before opening. After completing a reopening checklist provided by the health department, Nick called his food supplier to replenish the empty coolers. “We are receiving no briskets next week,” his usual meat supplier told him. He called another and secured the last ten cases of brisket it had in the building. Those fifty briskets would be enough to last just two days of service. He frantically reached out to anyone who might be able to ship him some meat. Ben E. Keith, a distributor in south Fort Worth, got back to him with good news and bad news. They’d have fresh briskets for him eventually, but the first shipment would be frozen beef. “Do you have any tips on cooking a thawed brisket?” Pencis asked me sincerely during our conversation, adding, “I’ve never cooked one.”

“You’re gonna get new friends in times like this,” Robby Austin, of Ben E. Keith, tells me. His title is “Category Manager; Center of the Plate,” but he prefers “Meat Head.” Austin distributes beef to dozens of barbecue joints and has a wealth of knowledge about brisket supply and demand. “It’s been a rodeo,” he says, exasperated about the massive swings in the market over the past six weeks. He’s been fielding calls from both tiny independent pitmasters and massive barbecue chains looking for the briskets that their usual suppliers can’t provide. “We’re trying to help who we can,” he says, but there are only so many briskets to go around.

The first crisis began when restaurant restrictions were announced in Texas in mid-March. Meat distributors like Sysco and US Foods panicked. A huge drop in consumer demand at the restaurants they supply was on the horizon. They canceled millions of dollars in meat orders. Delivery trucks were sent back to meat-processing plants still hauling their protein payloads, and the processors scrambled to find other buyers. Ben E. Keith, though unsure about the future and with only a trickle of beef leaving the building, continued accepting beef orders by the truckload. As its coolers reached capacity, it shifted fresh beef to its massive freezers—not an ideal move, because restaurants demand fresh beef; once it’s frozen, it loses value. But it had no choice. “We were almost putting it on the roof,” Austin remembers. The next swing in the market came just in time.

Many restaurants have been crippled by the pandemic, but barbecue joints closures have been few and far between. Though most pitmasters suffered a huge dip in their business for the first week of shelter-in-place orders, the rebound has been swift. “Out of every food segment there is, by far barbecue is number one right now, and it ain’t even close by numbers,” Austin says. Not a single barbecue joint that buys beef from him has closed, and, as mentioned before, Ben E. Keith has gained a few customers. Its Fort Worth distribution center shipped out 1,075 cases of briskets (roughly 5,000 briskets) in the first two days this week. “That’s about a week’s worth,” Austin says. Those freezers are mostly empty, and the frozen briskets are gone. “I’ve never gone to bed at night and not had a brisket in the building,” Austin says, but he’s expecting that will be the case this weekend. He has more beef shipments coming in Monday morning, or at least he hopes so.

The U.S. meat supply is tenuous at best. “At least 38 meatpacking plants have ceased operations at some point since the start of the coronavirus pandemic,” USA Today reported. And it wasn’t for lack of demand for meat; they were all closed because of positive COVID-19 cases among their processors. At many of the massive processing plants, it’s not a case of a few illnesses here and there. The workforce has been greatly affected by the virus. Of the 2,200 workers at a Tyson pork processing plant in Indiana, 890 tested positive. Seven hundred of 1,200 workers at a Perry, Iowa, pork processing plant, and 669 of 4,300 workers in a Tyson beef plant in Dakota City, Nebraska, were infected. At the Smithfield pork plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, nearly 800 of the 4,300 workers had the virus. In the Texas Panhandle, secluded and sparsely populated Moore County (and adjacent Potter County, home of Amarillo) has become an otherwise unlikely coronavirus hot spot because of the infected workers at the JBS beef processing plant in Cactus.

Those plant shutdowns, while certainly warranted for the safety of workers, their families, and their communities, have put a serious dent in the amount of beef and pork being processed in the U.S. Last week, the USDA reported that 1.55 million hogs were processed, compared with 2.37 million hogs the same week last year. There are four racks of ribs (two baby backs and two spares) in every hog, so that represents 3.28 million fewer racks of ribs on the market in a single week. And as for brisket? Last week, 425,000 cattle were processed, down from 605,000 cattle the previous year, meaning a difference of 360,000 briskets.

Those numbers are bad enough, but then consider the huge market for ground beef as consumer demand shifts from steaks at fine dining restaurant to drive-through burgers and bulk buying at grocery stores (more on the challenges of these two distinct supply chains later). When the demand can’t be met for ground beef (just try to order a triple cheeseburger at Wendy’s), the packers are going to grind briskets long before they reach for expensive tenderloins and ribeyes.

And maybe you’re thinking this will all be solved by President Trump’s executive order to reopen the meat processing plants. “It’s hard to know exactly what it means,” David Anderson, an agriculture economist at Texas A&M University, says of the executive order. He was giving his best guess of a beef forecast to a group of retailers and restaurateurs last week and had little positive news to share about pork and beef markets in the near future, other than: “We’re all gonna learn a heck of a lot about the supply chain for the stuff that we eat.” Law professor Daniel Hemel agreed with Anderson, and argued in the Washington Post that “[Trump’s] declaration does not—on its own—compel any action.” Since the executive order on April 28, seven more meat processing plants have closed

“We’ve got a bottleneck now at packing plants,” Anderson observes. Eighty percent of the beef in the U.S. is processed by Tyson, Cargill, National Beef, and JBS (the largest beef processor in the world), collectively know as the Big Four, but remember that this supply chain doesn’t commence there. Calves are born on the ranches and stay there until they’re sent to a feedlot for fattening. The feedlots then sell the fattened cattle to meat processors, including the Big Four, so a bottleneck in the packing plants affects them most severely.

Wendel Thuss raises cattle on a ranch near Seguin (and is also a friend of mine from college). His young cattle will be fine on the ranch until fall, when he’ll need to seek out a buyer. He’s not worried about his operation just yet, but he’s sympathetic to the feedlot operators. “The guys that are getting hosed right now are the feed yards,” he says, explaining that they’ve been feeding the cattle a steady diet of grain in anticipation of getting them sold to beef processors that either aren’t buying or aren’t offering much. (Eleven state attorneys general expressed concerns about collusion between the Big Four, writing “we have concerns that beef processors are well positioned to coordinate their behavior and create a bottleneck in the cattle industry—to the detriment of ranchers and consumers alike” in a letter to U.S. Attorney General William Barr seeking an investigation from the DOJ.) “Fat cattle are verging on free right now,” Thuss says. And as for the feedlot owners, “They’re backed up. Now they have overfat cattle. Now they’re putting feed in cattle that aren’t growing anymore.” Basically, the feedlots are spending lots of money on grain to add little value to a product that’s hardly worth anything.

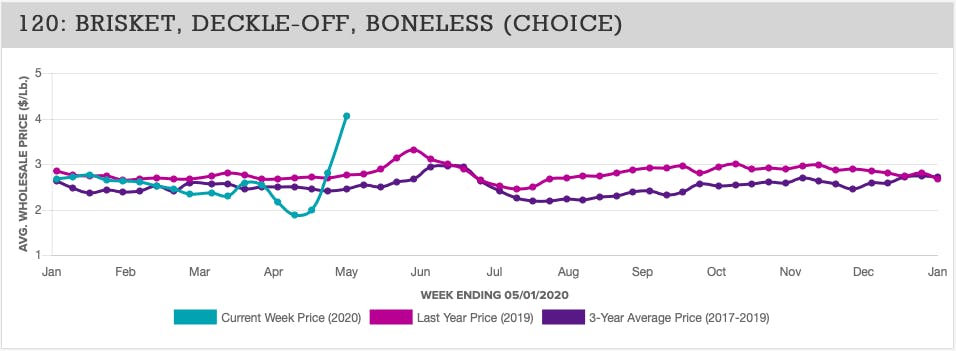

To get an idea of what the beef processors are bringing in on the other side of the supply chain, I looked at pricing data for the USDA. The “choice cutout price” is shorthand in the beef industry for the cost of processed beef. It’s the average cost of hundred pounds of processed Choice grade beef. The all-time record for choice cutout before this year was set at $265.59 on May 19, 2015. On April 24, 2020, it reached $293.37, and beef buyers gasped. It launched to $458.54 on May 7. Because it’s an average price, every cut of beef isn’t treated equally, but brisket buyers will not be spared. The weekly average cost for whole Choice briskets went from $2.80 per pound two weeks ago to $4.06 this past week, and the daily price on May 7 was between $5.46 and $6.50 per pound.

In Cameron, 44 Farms raises Angus cattle, which it markets under its own brand name. It’s widely regarded as some of the best beef in Texas, which is why chefs like Chris Shepherd, of Georgia James in Houston, and John Tesar, of Knife in Dallas, feature it on their steakhouse menus. The 44 Farms briskets and beef ribs are a favorite of barbecue joints, at least the ones that can get them. It has built a uniquely valuable brand for boutique beef, but many of its fine, high-end restaurant clients aren’t open. The briskets and ground beef were moving, according to Jason Schimmels, its director of sales, but not the “middle meats” like tenderloins, ribeyes, and strips generally sold at steakhouses. It chose to shut down processing lines, operated at Caviness beef processors in Hereford, for a full month.

“If we harvest two hundred head of cattle, what are we supposed to do with those ribeyes for the next three, four, or five weeks?” Schimmels asks. Employees had to move fresh steaks to the freezer, immediately lowering their value to chefs. “Ninety-nine percent of all our business is and has been food service,” he says, so they tested the retail waters. In addition to selling through the 44 Farms online store, a small grocer in the Northeast carried 44 Farms steaks for three weeks, but immediately went back to a more inexpensive supplier once that option became available. 44 Farms decided that offloading live cattle was a better option than adding to the freezer stock. Many of its cattle being fattened at Mc6 Cattle Feeders Inc. in Hereford were sold to other Angus beef operations, and Schimmels waited until he could get back to selling. Finally, 44 Farms received a purchase order from Ben E. Keith for steaks. It was large enough to crank the operation back up, and it began processing cattle again this week.

Bryan Bingham, pitmaster at the original Bodacious Bar-B-Q in Longview, uses 44 Farms briskets exclusively, but said he thankfully didn’t really notice a dip in production. “I’ve known all along that it was entirely possible,” he says about losing access to those premium briskets, but his coolers haven’t been depleted. “I ordered a little bit heavier than I normally would to ride the wave,” Bingham explains, and he credits some of the steady supply to a lower customer count at the restaurant. “I’m not going through as much brisket right now,” but business is still good enough for him to feel comfortable. “I honestly did not expect the support we’ve gotten from everyone.” As for the price of his briskets, it was already higher than most because he’s buying a premium product, but Bodacious isn’t seeing the spikes in brisket prices that other pitmasters will very soon be (or already are) dealing with.

The lesson from 44 Farms is twofold. Smaller beef suppliers whose prices aren’t driven by the wider beef market can be a port in a storm, as long as their drop in production can be weathered by distributors. (Ben E. Keith supplies those 44 Farms briskets to Bodacious.) But it also shows that if you’re not already part of the retail supply chain, it’s not easy to pivot and become part of it in a meaningful way, even if you’re a smaller, nimbler beef company like 44 Farms. The big processors supply both the restaurant and retail supply chains, but each acts as a funnel, and the two rarely cross. The “fat beef” that Thuss described earlier is reserved mostly for restaurants, which is funneled through distributors. That’s where the Prime grade beef primarily goes. The Choice and Select beef is funneled through the retail supply chain, which goes to grocery stores. The majority of grocery customers aren’t usually willing to pay a premium for the best quality steaks, and purchase far more ground beef than steaks anyway.

In a normal consumer environment, there’s a good mix between retail and restaurant customers for the beef supply. Today, retail sales for beef are far outweighing restaurant sales, and the restaurant sales have been dominated by a demand for ground beef at fast-food drive-throughs and brisket at barbecue joints. Steaks from fat beef that usually go for a premium are the odd man out. As Thuss explains it, “We regressed consumer preference thirty years overnight,” when the high-end restaurants closed. “Our market shocks are supply based,” he says, but what we’re seeing today is a shock from the consumer demand side, which never happens this rapidly.

Just look more closely at the ground beef from the grocery store to see the effects. Ground beef is usually made from lean cattle and older animals that wouldn’t make for great steaks because the beef is so lean. Now the fat cattle are getting ground up as well. There is an allowable range for beef that’s labeled 90 percent lean, so don’t be surprised to find some extra fat in your next package from the store. I buy 80 percent lean for my burgers at home, but I noticed the USDA is now tracking sales of 73 percent lean beef (which is 27 percent fat). When I mention that to Thuss, he explains, “Seventy-three is the maximum allowable fat content that you can sell in ground beef under U.S. law and still call it ground beef.” All that is to say that those fat cattle that usually fetch a premium from the beef processors are rapidly dropping in value. “A fat cow right now in a box is worth well over twice what it is standing up in a pen,” Thuss says, but that difference in value is normally 20 percent. From the perspective of the live beef market, Thuss believes, “We’re not at the bottom yet. We’re still on our way down.”

The question now is how quickly the supply from the beef processors will stabilize to bring overall beef prices down and live cattle prices up. U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced this week that he expected all the processing plants to be reopened soon. “I’d say probably a week to ten days we’ll be back up, fully back up,” Perdue said in a meeting with Trump and Iowa governor Kim Reynolds, but that may be overly optimistic. Even if the plants have reopened, they won’t likely be at full capacity. As David Anderson from Texas A&M says, “It doesn’t mean anybody’s going to show up,” referring to the workers. In an anonymous essay, an employee who says she works at a Tyson beef plant in Amarillo wrote: “I don’t feel critical. I don’t feel essential. I feel sacrificial.” Even if the workers are willing to return to the reopened plants, USDA inspectors are required for any plant to operate, and more than one hundred members of the already short-staffed inspector workforce have been infected.

Regardless, pitmasters will likely have to become less selective when it comes to the briskets they smoke. Robby Austin, from Ben E. Keith, expects a surge of Prime beef on the market as the feedlots are slowly emptied of their overfed cattle—and those briskets will be huge. Once the feedlot stock has dwindled, ranchers who have held out for a good price for live cattle will reenter the market with larger animals that have been exclusively fed on grass. Adding intramuscular fat with grain in the feedlots (necessary to produce Prime grade beef) will be a challenge before the animals have reached slaughter weight, so expect the amount of Prime beef being processed to decrease later this year.

As for specialty beef programs, it might be harder to come by organic or all-natural beef. At True Texas BBQ locations inside H-E-B grocery stores, they smoke all-natural Prime grade beef exclusively. H-E-B’s director of restaurants, Kristin Irvin, says they don’t currently have a shortage of their preferred beef for the restaurants, but they do have a plan B of conventional Prime briskets if necessary. They at least have the advantage of buying power that most restaurants don’t. “The same meat buying team that buys for retail is the one that buys for restaurants,” she explains.

All but two of the True Texas BBQ locations in the state have reopened after initially closing in mid-March (there’s not a current plan to open the dining rooms), and business is slowly building. Irvin said the grocery customers were happy to see barbecue return, but the people who used to pop in just for lunch are slow to return. As for those increased brisket costs, Irvin says they’ll try to keep from raising prices at the True Texas BBQ counter. “Texans are feeling the pinch on their wallet, so we’re going to do everything we can to hold prices steady,” she says. I ask whether they considered featuring other proteins given the grocery store inventory at their disposal. Her answer: not yet. “There was a little talk about goat, but I don’t think that’s a flavor profile we’re ready to go for right now,” she says. I mentioned that smoked strip loins may be a better option, given their yield, if brisket prices crest $6 per pound. She laughs and says, “I might have to have them throw one in to see.”

Pitmasters and customers are simply going to have to brace themselves for these (hopefully) short-term price spikes. Riverport BBQ’s Stephen Joseph tweeted on Thursday that he found Choice brisket for $4.99 per pound. John Mueller says he was quoted $5.98; Bryan McLarty, of 407 BBQ, says, by the end of May he’ll be paying $6.30 a pound for brisket.” Matt Proctor, of Stillwater Barbeque in Abilene says, “Sucks but looks like it’s time to move on from brisket for now. [I’m] going to chicken fried chicken and ribeyes.” Austin thinks that’s a good idea: “I’d look at smoking a prime rib,” he advises.

One meat segment that isn’t spiking is poultry. The price for chicken wings is way down thanks to just about every sports bar in America being closed. Chicken leg quarters and boneless turkey breast are also down in price, so pitmasters and customers both may need to be more open-minded in the near future, or willing to shell out $30 a pound for smoked brisket. Reid Guess, of Guess Family Barbecue in Waco, said he still has a solid supply of briskets from Creekstone Farms, but understands that relying on a single supplier makes him vulnerable. “Not cooking brisket for a little while might not be the end of the world,” he says. It’s painful to say, but Texas may have to take a short break from being the brisket state.

- More About:

- Brisket