The gently curved “hump” atop the Alamo is the signature not just for the city of San Antonio but also for countless businesses around Texas, from the Valero Alamo Bowl (which takes its name from the shrine’s original name, La Mision del San Antonio del Valero) to breweries, title companies, and pest control firms. It’s on both the official seal and the flag of the city of San Antonio. The hump may be the most iconic image in Texas history.

But it wasn’t there during the Battle of the Alamo.

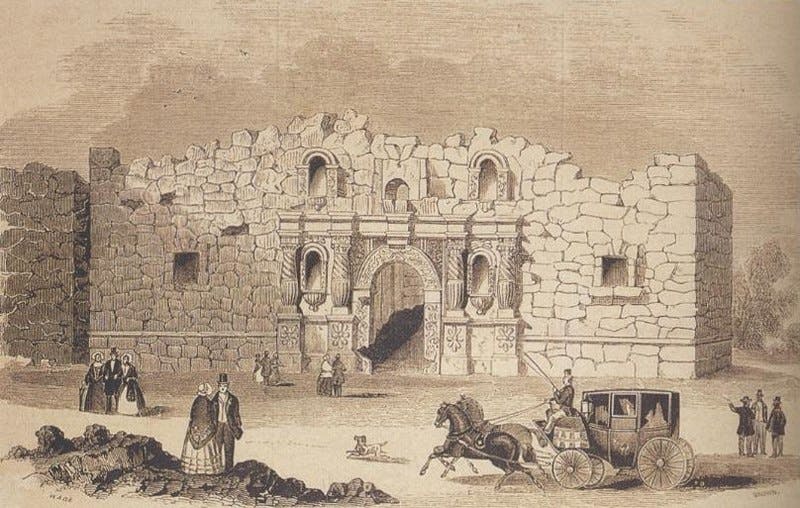

Despite all those paintings and illustrations you’ve seen, the Alamo defenders were not up on the roof sniping Mexican soldiers from behind that hump. There wasn’t even a roof to stand on atop the church during the 1836 battle, much less what has become erroneously known as a parapet to hide behind while taking potshots at advancing Mexican soldados. In fact, the Alamo didn’t grow its hump until a century after the mission’s construction.

What has come to be known as the Alamo began its life as San Antonio de Valero, one of the five missions founded by Spanish Franciscan friars in the San Antonio area in the early eighteenth century. These missions, not unlike some Israeli kibbutzim, were intended to provide both food, grown in the fields in and around the missions, and mutual defense against hostiles — in San Antonio’s case, raids from Apache and Comanche Indians.

San Antonio de Valero was intended to be the crown jewel of the mission complex. According to the Texas State Historical Association, architectural plans for the church — what we commonly know of as the Alamo today — called for a three-story edifice topped by a dome, flanked by twin bell towers, and inside, a choir loft and a barrel-vaulted roof. Even more elaborate carvings were planned for the facade, including statues of four saints in the niches. (The statues may have existed at one point.)

But the mission, cursed with natural disasters and construction mishaps, never made it to that exalted status. The Spaniards had to move it three times before it landed on its present site in the early 1700s. In 1724, the remnants of a Gulf Coast hurricane knocked down what had been built on the site. The Spanish rebuilt, but in 1744, it collapsed on its own accord. The magnificent towers and ceiling did briefly exist in 1757 — but five years later, the structure fell in on itself, and it was never rebuilt to the original plan.

After the population of Christianized Indians dwindled over the next few decades, the Catholic Church secularized the complex in 1793, assigning its few remaining denizens to the nearby parish of San Fernando, which is still San Antonio’s cathedral.

In the 1800s, control over the complex changed hands seventeen times. The Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras, a Spanish cavalry troop that hailed from the town of San José y Santiago del Álamo in the northern state of Coahuila, in today’s Mexico, briefly used it as their headquarters. (Many believe it was their occupation that gave the building the name “Alamo,” which means cottonwood or poplar tree.) Between 1810 and 1865, control of the complex switched from Spanish to Mexican and back during various rebellions, then from Mexican to Texan to Mexican and back to Texan in 1835 and 1836, then to American in 1845.

Upon annexation, the United States army requisitioned the decaying unfinished church as a storehouse. A junior officer wanted to tear it down and replace it with a more modern structure, but he was overruled by his superior, General Thomas S. Jesup, who instead ordered the building restored. (In typical San Antonian Germanic/Hispanic fusion fashion, the same kind you can hear in the city’s music to this day, the originally Spanish structure was added on to by a Bavarian-born architect — one Johann Fries — who also designed the Menger Hotel, and whose plans won over General Jesup.)

Because the army requisitioned the old church as a storehouse, it needed a roof to protect the goods inside. “The cheapest roofs were pitched roofs, and the best way to hide a pitched roof is to put up a gable on the front,” says Jesús Francisco de la Teja, a historian at Texas State University. “A pitched roof didn’t really look right behind a flat surface, and since that third floor was never added, they needed something to hide that roof.”

What could hide the roof of a supply depot? A hump, or “campanulate,” the technical term architects use for bell-shaped facades like that at the Alamo.

Although we now see the hump as an iconic representation of Texas’s history, not everyone was a fan of the addition.

Just before the Alamo overhaul, English-born watercolorist Edward Everett, then a 28-year-old sergeant in an Illinois militia headed off to fight in the Mexican War, was assigned to the duty of “making drawings of buildings and objects of interest, particularly those in the neighborhood of San Antonio.” About his visit to the Alamo, he wrote, “we respected [it] as an historical relic — and as such its characteristics were not marred by us.”

Decades later, when he wrote his memoirs, Everett was dismayed to see what Fries had done to the ancient, battle-scarred, tumbledown pile he had known in his days in San Antonio, likening its new appearance to that of commonplace furniture.

I regret to see by a late engraving of this ruin, that tasteless hands have evened off the rough walls, as they were left after the siege, surmounting them with a ridiculous scroll, giving the building the appearance of the headboard of a bedstead.

During the Battle of the Alamo, the most identifiable structure in the history of Texas didn’t look anything like the building we recognize. It took a renovation from the U.S. army — not Spanish friars, Mexican priests, Texan rebels, or Confederates — to shape the Alamo structure we know today.