It was probably somewhere on a two-lane highway in North Texas below the Red River. I was thirteen, scrunched in the back seat with my two brothers and sister on our way to visit family in Oklahoma for Christmas. I stared blankly outward at the world, my imagination in neutral. The winter scenery was not scenery. Fields. Flatness. Barbed wire fences, pale sky, birds whose names I didn’t know and didn’t at that time in my life care to know huddled together for warmth on telephone wires. Rusting cars, pump jacks, unpainted houses standing all alone in worked-over expanses of dirt where some crop that may have been vital to my existence but was numbing to my soul had long been harvested.

Nothing to see, nothing to think about. But something came into my head, and it was this: I must remember this moment for the rest of my life. It was a random resolution that arrived with the force of an epiphany. I needed to hold this arbitrary, pointless scene in my head, set it down as some kind of benchmark, return to it again and again. It would be my first conscious deposit in the bank of memory. Barely a teenager, I was romantically imagining my own future nostalgia. I could already feel time as a vast sea that would sweep over me and sweep me away unless I dropped an anchor somewhere.

That was 1961. It is sixty years later, and the anchor still holds. There have been years, maybe even decades, when I didn’t bother to heed my childhood command to remember that moment, but I could confidently trust that it was still there. Nowadays, I tend to return to it much more often, the way I habitually pat my pants pocket to reassure myself that I haven’t misplaced my keys.

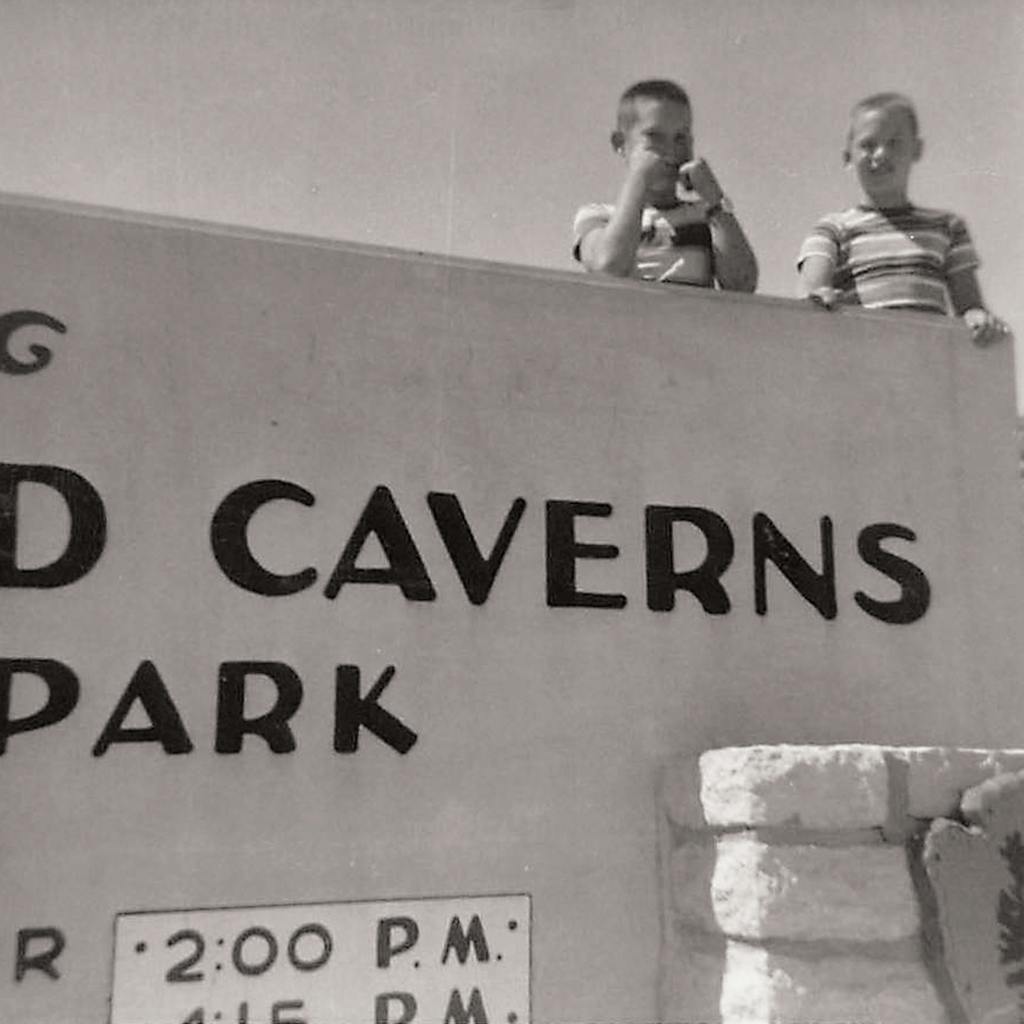

That enforced memory in the car on the road between Abilene and Oklahoma City is only one data point, one fragment of proof that I have actually lived my life. What astonishes me now is that’s all that my memories are made of: data points. I know people for whom the past seems to be an unbroken stream of recollection. From the age at which memories typically form—about three years old—the movie is continually running for them. They recall every grade-school teacher they ever had, the month and year of every trip they ever made, every detail of the unfolding lives of themselves or their children.

Not so for me. At best, I have a connect-the-dots memory, and many of the dots I once innocently counted upon to be indelible have turned out to be, over time, invisible. Recently, it occurred to me to ask myself: What did I do on my twenty-first birthday? No idea. I would have known at the time it was a landmark event, the day on which I officially became an adult, old enough to vote, old enough to drink. I was a student at the University of Texas, living in Austin with three other students in an old house that we had christened, with droll exuberance, Mike the House. I know that because we had made a sign that said Mike the House and nailed it by the front door, and there is a picture of me posing next to it.

But I can’t really recall anything that went on in that house. I don’t even vaguely remember what it felt like to wake up there on that morning of my twenty-first birthday. I wish I could blame that particular lacuna on a rite-of-passage spree from the night before, but since I’ve always been a nondrinker, I’m faced with just a blank. Because I neglected to drop a memory anchor, the events of that supposedly memorable day have now vanished as if they had never existed.

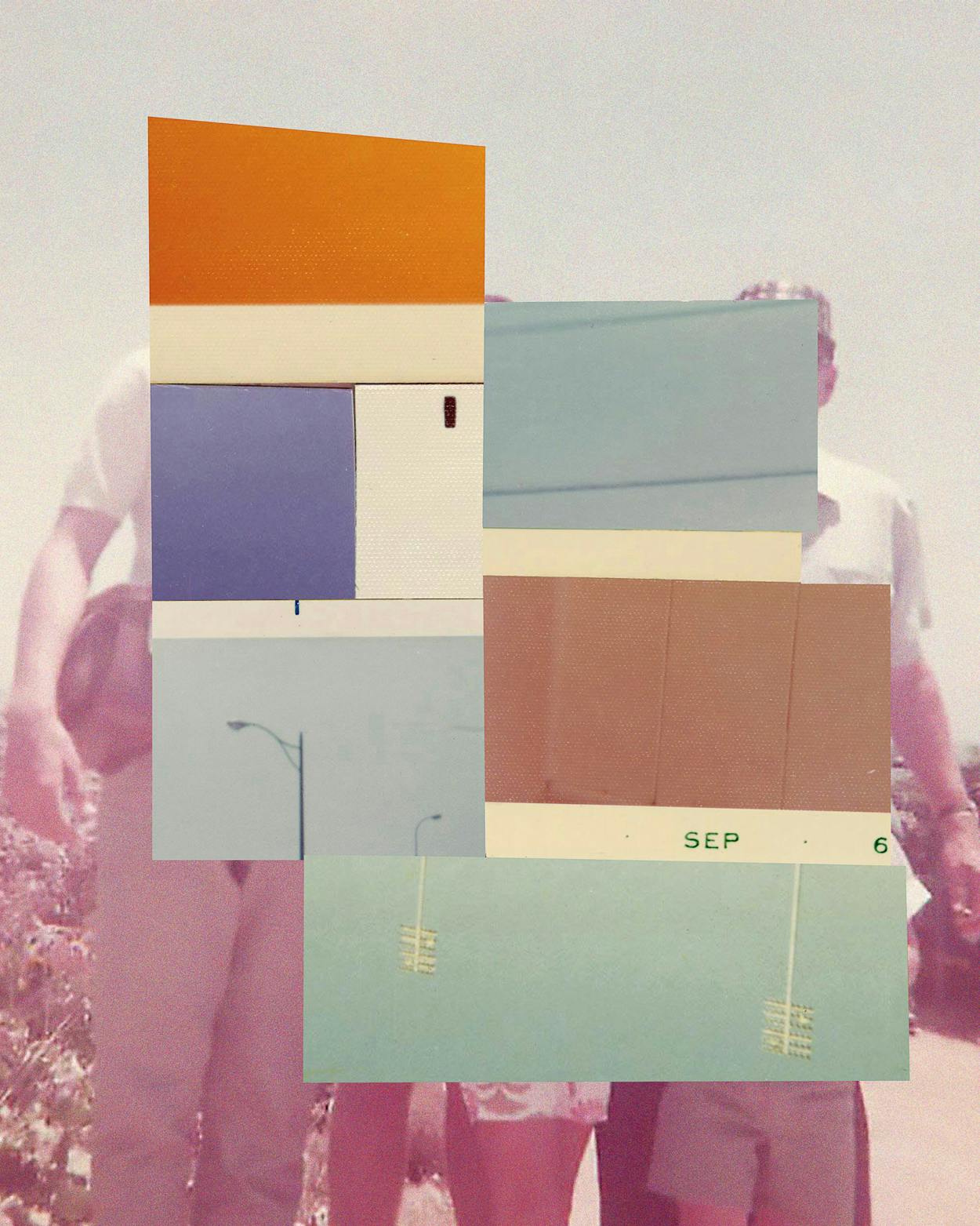

A few months ago, I got a photo scanner and embarked on the project of digitizing over a dozen family photo albums, along with hundreds of other images that had never made their way into the albums and are overflowing out of shoeboxes and drawers all over the house. It’s a time-consuming task and, I’m finding, a somewhat demoralizing one. Every time I carefully peel one of those yellowing photos from beneath the “protective” plastic that covers each album page, I feel assaulted by the fleeting reality and hurtling velocity of the lifetimes chronicled there.

But that’s to be expected. There’s no point in observing, much less complaining about, the universally understood fact that time passes. Sometimes the photos in those albums act like a shot of adrenaline, dilating my atrophied recall networks with a rush of energy that makes lost times feel achingly present. But just as often the images don’t reinforce my memory—they taunt it. They accuse me of the crime of not paying sufficient attention to the life that I was then living. Failing to take notice—to set down some sort of deep-brain marker—turns out to be an existential offense: time passes, memory passes with it, and all that’s left is an unmoored consciousness groping to remember.

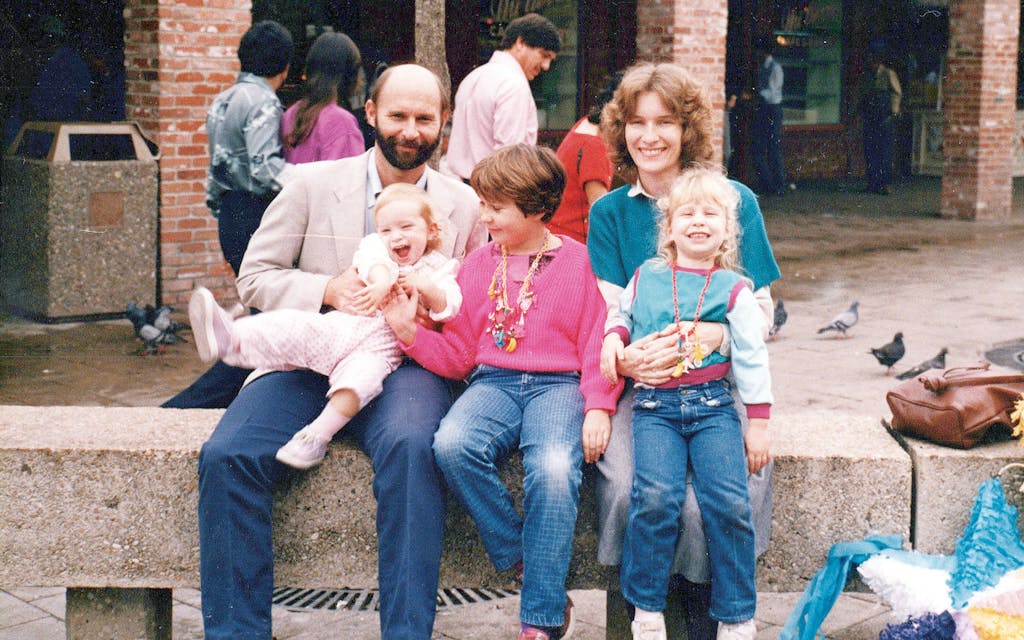

I’ve kept a journal for more than forty years, precisely because I was determined not to let this happen to my future self. But whether I’m reading over the pages I’ve written or looking at the photos I’ve taken, most of the time it’s evidence, not memories, that I encounter. Yes, I can confirm that that was the Thanksgiving we spent with my wife’s parents in Ruidoso, New Mexico. Yes, the available data suggests that on at least one weekend we drove the kids to San Antonio and went to the zoo and had lunch at Mi Tierra. What’s gone—what’s as impalpable as a ghost—is the narrative: the connective tissue of memory binding one photo or journal entry to the next. So much is known to have happened but is functionally unremembered: the long days and years of getting up every morning, getting the kids to school, embarking on unexceptional reporting or research trips for a book or magazine article I was writing and then coming home and weathering day after day the mild-to-intense anxiety of composing it.

Movies were so visually powerful, especially when I was young, as to seem unforgettable. They don’t seem that way anymore. “Have I already seen this movie or not?” is the once-unimaginable question I’ve had to get used to posing to myself.

I suppose I trusted that the big moments—the ones worth remembering—would automatically be filed: the night I met my wife and we shared a Dr Pepper and then went to see a spaghetti western called My Name Is Nobody. The births of our three daughters, the deaths of parents and of friends. But I’m haunted by the knowledge that I might be capable of forgetting even those things—not the facts of them but the tenor and tone of them—and from time to time I’ve studiously played that highlight reel over and over again in my head, subjecting my memory to a kind of stress test. To fail that test would be an indictment not just of my recall but of my character.

There have been times when I did command myself to remember something, in the way I did on that car ride when I was thirteen. But unlike that pointedly unremarkable slice of life, these were usually moments of supreme happiness or supreme wonder: The time when my wife and I and our oldest daughter—pregnant with our first grandchild—sat in Radio City Music Hall to watch the simultaneous graduation of our two younger daughters from Hunter College; the time when, diving at ninety feet in the Celebes Sea off the coast of Malaysia, I looked up and saw hundreds of hammerhead sharks silhouetted against the surface sunlight, all of them swimming onward with silent, alien urgency.

For most of my life, reading books and watching movies felt like experiences that would naturally be protected in the fireproof filing cabinet of memory. Movies were so visually powerful, especially when I was young, as to seem unforgettable. They don’t seem that way anymore. “Have I already seen this movie or not?” is the once-unimaginable question I’ve had to get used to posing to myself. And I won’t be talking about a creaky classic on TCM that I could be forgiven for forgetting after so many years—more likely some recent Liam Neeson revenge thriller or some somber domestic drama from two years ago that was nominated for an Academy Award.

Because reading a book requires so much time and concentration, I used to believe I could count on remembering at least the characters and basic plot of a novel or the central thesis of a work of history. But the other day someone was talking about The Good Soldier, by Ford Madox Ford. I read that book in college and again about ten years ago. What was it about? I could check Wikipedia, but that would be cheating. I honestly don’t have the slightest idea. In an earnest effort to educate myself about the Byzantine empire, I once spent the better part of a week reading a book about the siege and fall of Constantinople. I don’t remember the title or the author or anything that happened in Constantinople during whatever year the siege took place. All that I’ve retained from that book is a fuzzy mental image of a collapsing wall—I think from a cannonball, but I’m not sure.

Writing a book is different than reading one. After I’ve published a book, what I can’t remember about it somehow feels earned, as if to write well required me to wring dry my entire awareness of the subject. That’s the lifeline I’ve always offered to myself when trying to understand how I could spend months on a magazine article or screenplay and end up not recalling its central premise or even that I had written it at all. I recently published a nine-hundred-page history of Texas that took me six years to write, and now I cringe in alarm whenever I anticipate that somebody is going to ask me a direct question about it. My nightmares these days often involve being called upon to explain the Neutral Ground agreement of 1806 or the origins of the Sharpstown scandal in the 1970s. At this point, I’m not at all sure I could pass a seventh-grade Texas history test.

Is this a function of age? Certainly, at least some of it. Retention—other than bladder-related—is not one of the hallmarks of a septuagenarian male. But I’ve been in the business of forgetting for so long and so consistently that I don’t think age is the whole story. When the coronavirus pandemic began, I read about teachers exhorting their students to bear witness to the history they were living through, to keep notes so they could safeguard the details of this extraordinary time for future historians and for their future selves. I meant to do that as well, but the startling developments of 2020 and now 2021 have come tumbling along so fast, with so many crucial things to remember, that it seems the tape is being erased even as it’s being recorded. I must have sensed the evanescence of recall as far back as 1961 on that car trip; otherwise why would it have been so important to me to make an effort to place a bookmark in the thin volume of my thus-far life?

And perhaps I may have had some unformed suspicion of what I now know consciously, that there is a kinship between forgetting and not-being. As memories fall away and your own past becomes more of an abstraction than an assertive definition of who you are, you begin to receive hints of how your life will someday drop without a splash into the stream of nothingness that was there before and that will come after.

All the more reason, then, to try to trap the moments like lightning bugs as they pass by, though it probably runs against the grain of human instinct to experience and to record at the same time. That’s one reason I’m grateful that, all those years ago in the back seat of a car on the Texas plains, a warning came to me out of the blue: remember to remember this moment, or let it go forever.

This article originally appeared in the June 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “An Anchor in the Sea of Time.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Austin