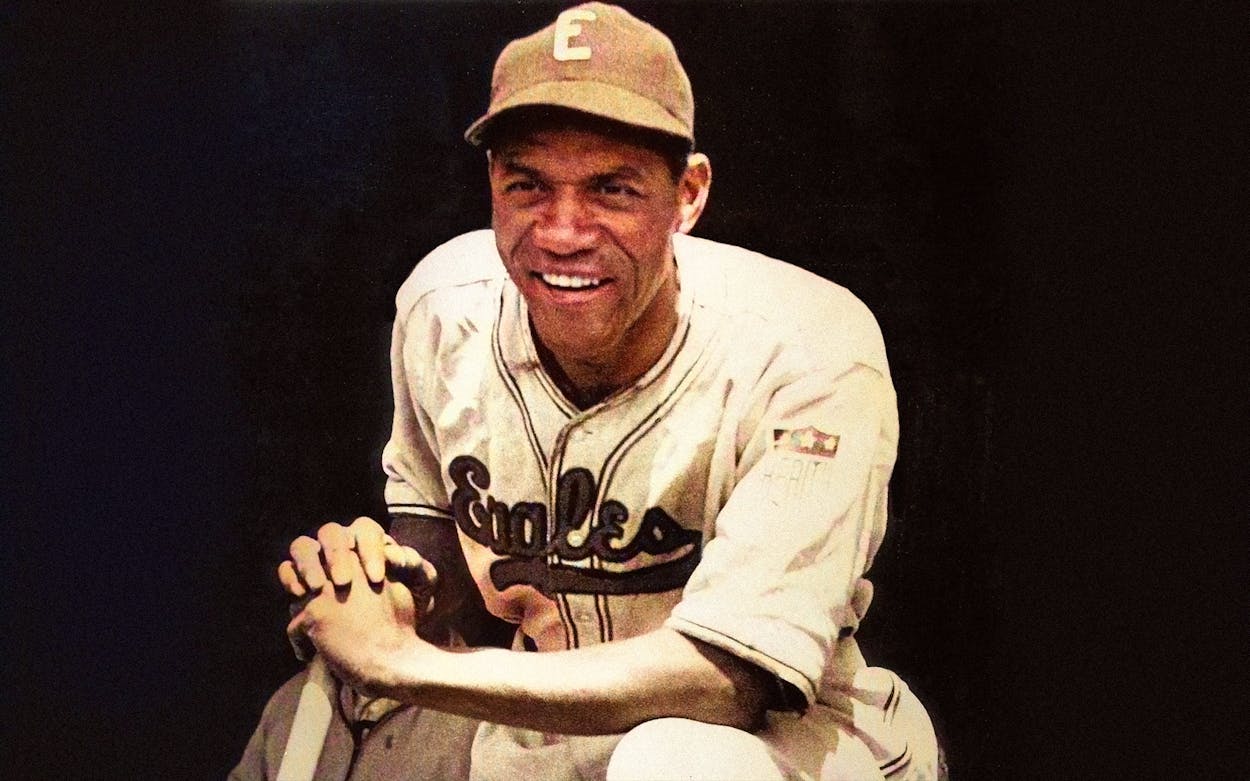

One afternoon in 1939, Willie Wells stepped up to the plate in Buffalo, New York, clutching a bat in hand. As a seasoned ballplayer in his early thirties, Wells had shored up a reputation that made his opponents quiver in their cleats: a standout shortstop for the Newark Eagles, a Negro League team based in New Jersey, Wells was known for his prowess in this critical defensive position tucked between second and third base—and the fact that he flexed a decent share of home runs. “Ballplayers could not get the ball past Willie Wells,” says Larry Lester, a historian and cofounder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. “He was a great shortstop who could hit, which was not the norm back then. Most shortstops and second basemen were not power hitters. But Willie Wells was.” His consistency and dominance as a hitter often led rival pitchers to hurl the ball at Wells’s head in an attempt to derail him; a few years earlier, Ray Brown, a phenom pitcher for Washington’s Homestead Grays, had socked Wells with a mighty pitch that landed him in the hospital.

That day in Buffalo, Wells went to bat against the Grays once again. He wore something unusual on his head, though: a coal miner’s hard helmet sans the light. Fellow players couldn’t understand why he’d shown up sporting such an odd contraption. But when the Grays’ pitcher Tom “Big Train” Parker chucked the ball at Wells’s dome, the helmet took the beating instead of his head. As Bob Luke notes in his book Willie Wells: “El Diablo” of the Negro Leagues, Wells got “knocked down” from the pitch “but got up to hit a triple off Parker’s next offering.” Still, the batting helmet wouldn’t catch on for another dozen years, and Major League Baseball wouldn’t make it mandatory until 1971 (and then only for new players).

“I give him credit for wearing the first protective covering for his skull in either the Black or white leagues,” Lester adds.

Despite his inventive contribution to baseball technology, Wells is rarely mentioned in the same breath as, say, Roger Bresnahan, who’s lauded for the batting helmet prototype he came up with in 1907. Or Charlie Muse, the Pittsburgh Pirates executive who helped create the plastic helmet that’s since become essential to the game. It’s a glaring omission, particularly considering that Wells was “perhaps the greatest shortstop who ever lived,” as Gary Cartwright once wrote in this magazine, a man dubbed El Diablo for the uncanny way he took runners out. “How a lot of people look up to LeBron James today, I think that’s how they looked up to Willie Wells,” says kYmberly Keeton, the African American community archivist and librarian at the Austin History Center, who is related to Wells by marriage. Wells was committed to mentoring the next generation of great players and is said to have crossed paths with a young Jackie Robinson before Robinson famously broke the color barrier. In his later years, Wells returned to his hometown of Austin, where he coached Little League and lived in relative obscurity before his death from congestive heart failure on January 22, 1989.

Since then, Wells’s community has refused to let his spirit die. For the past three decades, his former neighbors, friends, and at least one Texas legislator have worked to ensure that the trailblazing ballplayer’s home became a historical landmark, that he was laid to rest in the Texas State Cemetery, and, most important, that he received long-overdue credit for his contributions to advancing baseball: specifically, for devising the first batting helmet engineered by a modern professional baseball player and for his achievements as one of the most versatile shortstops to ever grace a field. Additionally, the centennial of the Negro National League’s founding, which was celebrated in February 2020, has sparked a renewed interest around the world among baseball fans yearning to know more about Black players’ life stories and legacies—including Willie Wells. “All of these communities want to know: ‘What is our connection to this history?’” says Raymond Doswell, vice president of curatorial services at Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Accounts of Wells’s birthplace and birthday vary, though historians believe he was most likely born in Austin in 1906. He grew up with his mother, Cisco White Wells; his father, Lonnie Wells; and four brothers—Ira, James, Joe, and Nathaniel—in South Austin. He fell in love with baseball in elementary school, when he would play catch with friends after finishing chores and homework. Wells would reportedly pocket the nickel his mother gave him to put in the collection plate in church, then use it to hop on the South Congress trolley to Dobbs Field, near today’s Tom Miller Dam. There, he’d watch Black baseball teams from all over the state. To get closer to the action, an industrious young Wells often offered to carry players’ gloves and bats.

As a teenager, Wells began playing baseball with the semipro Austin Black Senators, often competing against other Negro League teams around the state. He also joined the San Antonio Black Aces and Houston Buffaloes for brief stints. At eighteen Wells was offered a contract to play baseball for the St. Louis Stars, and he accepted. After a successful 1924 season, he returned to Austin and started his freshman year at Samuel Huston College. But much to the chagrin of his mother, who wanted him to attend college instead of playing baseball, he lasted only a few months: Wells took a train to California when his former team asked if he wanted to play that winter season. He went on to play professionally for the next thirty years, joining teams on the East Coast as well as in Cuba, Canada, and Mexico.

Wells was an unorthodox shortstop. He didn’t have the most powerful arm, which is normally a prerequisite for the position. But he earned acclaim regardless for his even-keeled play and his penchant for making quick calls, as well as his ability to play to his strengths: he situated himself shallow, a bit closer to home plate. Wells’s potent swing also often earned him a spot as third in a batting lineup on practically every team he played on—a slot typically reserved for the best hitter, according to Lester. “When he went to the All-Star Game, he battled in the third slot,” he adds. “So he was the best among the best.” He was later dubbed the Shakespeare of Shortshops.

Black baseball players, Wells included, have long been resourceful as a means of self-preservation. Doswell says this stems from the late nineteenth century, back when Black and white players occasionally shared the field before the leagues were segregated. Black players tied the wooden staves from barrels to their shins to protect themselves from injuries. “When they played the infield—not catcher, infield—their opponents would come in with shoe spikes high to try to hit them in the legs,” Doswell says, adding: “Especially for a Black baseball team, you didn’t always have the resources as readily available to you for doctors and trainers and things like that, so you tried to stay in and play as much as you could, even if you played injured.” That’s how Wells came to repurpose a coal miner’s helmet as a protective shell.

So why is Willie Wells not as well-known as, say, Willie Mays? A lack of media coverage was part of the problem. The mainstream white press barely covered Negro League games and players during Wells’s heyday. When they did, reporting and statistics could be scant. Lester, who grew up close to the former Municipal Stadium in Kansas City, says the stories of Black ballplayers he mythologized in his youth were carried on through oral histories and testimonies in his community. “Growing up in my neighborhood, we celebrated the Negro League veterans who I never got to see play, but they were held in high esteem,” Lester says. “Once they got outside the neighborhood, they were unknown, unheralded, unappreciated, and unrecognizable. They were just another Black man.” Black newspapers covered standout players and printed play-by-plays of big games in the early- to mid-twentieth century, but little data exists for minor-league or semi-pro teams such as the Austin Black Senators. Black ballplayers’ statistics and achievements were so sparsely reported that in 2000, Major League Baseball gave the Baseball Hall of Fame a $250,000 grant to have historians, including Lester, conduct a thorough study of African Americans in baseball from 1860 to 1960, as well as an audit of their statistics.

While that study brought more attention to the achievements of Black baseball players, it’s just a start. Historians would like to see more comprehensive information on players including Wells, particularly as many details of his life—like his time playing with semi-pro teams in Texas and his later years—remain scarce. There’s also an urgency to venerate accomplished athletes during their lifetimes; Wells hoped he would be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, in Cooperstown, New York, but as he once told his daughter, Stella, “They’re not going to recognize me until I’m dead.”

The late Danny Roy Young, a local mover and shaker known as the Mayor of South Austin, advocated for Wells’s inclusion in the Hall of Fame starting in the late 1970s, when he met the former ballplayer while volunteering for Meals on Wheels and delivering hot food to Wells. Luke’s book notes that Young also had Wells’s face painted on his “Great Wall of South Austin,” a mural emblazoned alongside his restaurant, the now defunct Texicalli Grille. Democratic Texas congressman J.J. “Jake” Pickle also pushed for Wells’s inclusion, writing in the Congressional Record of 1980 about how he’d pleaded with the commissioner of baseball and the selection committee “to look once more at the records of Willie Wells.” In 1997, nearly a decade after her father’s death, Stella Wells was notified that he would be the fourteenth Negro leagues player to be honored in the Hall of Fame. In her acceptance speech that day honoring her father, Stella said: “To my father, baseball was more than a game. It was a way of life. He understood the importance of applying hard work, wisdom, intelligence, leadership, and persistence to his primary goal to win a baseball game. He sought to improve the game and at the same time protect himself from the hazard of injury.”

Seven years later, at the urging of Austin residents and baseball fans, Wells was reinterred from the city’s small Evergreen Cemetery to the Texas State Cemetery. He’s flanked by fellow prominent Texans including Barbara Jordan and Jerry Jeff Walker, with a headstone prominently displaying his many accolades. A little over a mile down the road from the cemetery lies Downs Field—one of the places where a young Willie Wells learned to love baseball, the site he returned in his later years to help teach young children how to bat, and the current home of Huston-Tillotson University’s baseball team. From his resting place on that grassy knoll, Willie Wells still presides over the game.