The woman is suspended in flight. Hanging from a trapeze by only a thin rope, the famous aerialist known as Barbette twists and turns with the delicacy of a swan. She cheats death with each plunge and gyrating movement; the audience’s attention is riveted as their eyes follow her body. The bouncy notes of a piano keep the tempo as orchestral strings emphasize the fluidity of Barbette’s performance. Clad in a fanciful sequined dress and an ostrich-feather hat, the slender but strong woman is a starlet, an enchantress. Her porcelain skin, powdered white with makeup, contrasts with her dark lipstick; her high cheekbones are evident even from the highest of theater boxes. Everyone wants to be her, to know her, but more importantly, everyone wants to love her.

Barbette’s leg, muscles rippling, hooks around the trapeze as she swings and twists herself upside down with a force so powerful it’s mystifying. She gently descends, and an assistant steps forward to wrap her in a feathered shawl. A knowing smile plays on her lips. She just gave a performance that no one in the crowd will forget. The applause is thundering when she ends the show the way she always does: by removing her curly blond wig to reveal the short brown hair underneath. Barbette was a man named Vander Clyde Broadway, from Round Rock, Texas.

Today, hardly anyone remembers his name. But in the 1920s and thirties, long before drag was mainstream, Barbette was a gender-bending international icon of vaudeville. He lived a glamorous life in Paris, counting among his friends fashion designer Coco Chanel and an eccentric lesbian princess named Violette Murat. The roaring twenties in France were Barbette’s playground. During that brief period, at least among the creative upper class, gender fluidity was widely accepted. Barbette’s charisma, combined with his exceptional talent as an aerialist, made him a muse for Jean Cocteau, who included the performer in his experimental film The Blood of a Poet. Barbette also influenced Alfred Hitchcock’s Murder!, which features a character based on him. Later in life, back in Texas, he would struggle with chronic pain. But at his zenith, Barbette (who frequently used his stage name in his offstage life) was one of the most captivating theatrical performers the world had ever seen. How did a kid from Central Texas end up at the Moulin Rouge?

It all started on the railroad tracks. As Barbette would later recount, as a boy he often walked the Great Northern Railroad tracks not far from his house on Anderson Avenue, balancing on the rail and pretending he was on a tightrope. (On a bridge high over Brushy Creek, it felt less like pretending.) In the backyard, he practiced on a galvanized metal clothesline. His family was working class, with his mother, Hattie, working as a milliner. Vander was likely born in 1899 (the exact year is in dispute). His father died before Vander’s birth, and Hattie later married a man who worked in a broom factory. Vander found his calling early, when his mother first took him to the circus in Austin. He picked cotton in the summers so he would be able to afford return trips. “I was spellbound by it all, and that is when I started to try the trapeze, the wire, the iron jaw, etc. . . . That was for me,” he would later write. He graduated high school early, at age fourteen, as valedictorian of his class at the Round Rock Institute.

Broadway soon caught his big break in San Antonio, where a group called the Alfaretta Sisters (“World Famous Aerial Queens”) was in need of a new member. He answered an ad in Billboard magazine and got the job. “No, I did not in the least mind being dressed as a girl,” he later wrote. “Certain parts of my nature were known to me before I became ‘Barbette.’ ” (This was as close as he would come, throughout his 73 years, to speaking publicly about his sexuality.) From there, the artist joined a circus trio called Erford’s Whirling Sensation—the performers often hung from a spinning device by their teeth—and then progressed to his own solo act. He debuted as Barbette in New York City in 1919, captivating a Harlem Opera House audience with the move that would become his signature: pulling off his wig. He followed this by flexing his muscles and showing them off, deliberately emphasizing his masculinity. “It wasn’t drag. It was something else. Some other thing that I’m not sure we really have a version of,” says David Goodwin, a theater teacher from Dallas who cowrote an eponymous play about Barbette. “The idea that you could sort of seduce an audience and make them believe that you’re a woman almost exclusively through the way you’re moving is really interesting.”

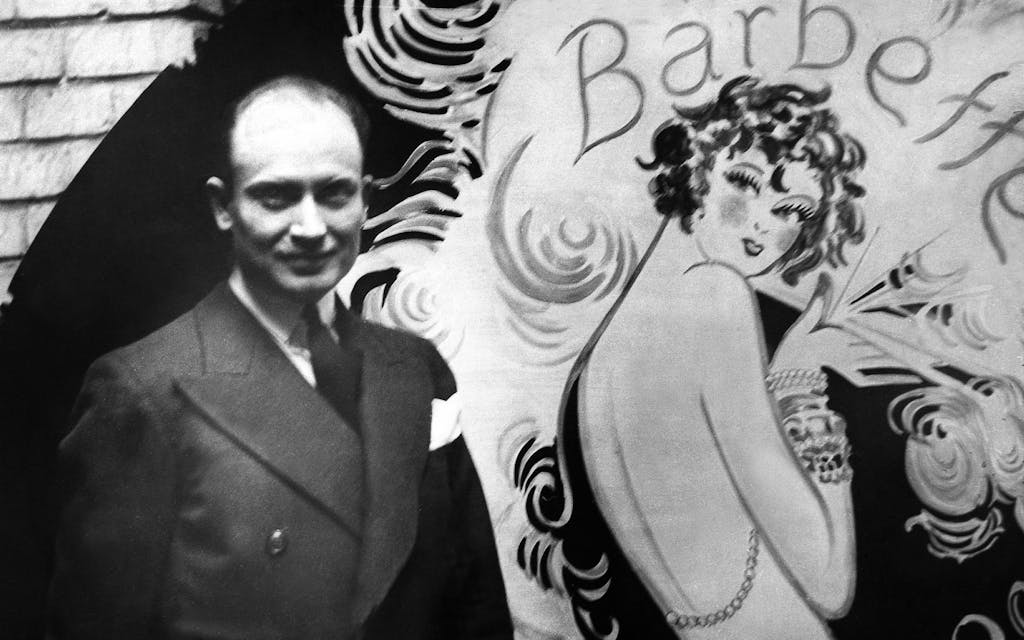

Word of Barbette’s skill spread, and he signed with the William Morris Agency (now WME), which remains one of the world’s biggest talent agencies. Starting in 1923, the company sent him to London and then Paris; his name quickly appeared on marquees, playbills, and circus posters. He toured internationally, mesmerizing audiences with each seemingly effortless performance, then shocking them every time he revealed himself to be a man. Confident and captivating, he was a sensation, and seemingly all of Europe was moved by him.

Among the believers was Jean Cocteau: esteemed poet, filmmaker, critic, and lover. The two had a secret whirlwind romance, with Cocteau documenting his affection for Barbette in the essay Le Numéro Barbette as well as in letters to friends. He was enthralled by the performer, and believed “his female glamour and elegance [were] like a cloud of dust thrown into the eyes of the audience, blinding it to the masculinity of the movements he needs to perform his acrobatics.” Barbette’s most prized possession was his ability to transform and persuade; he followed a punishingly strict exercise and diet routine to keep a lean, feminine figure. Cocteau was attracted by this, and made it known to anyone who would listen that Barbette was his greatest muse. While the performer enjoyed the attention and the glamorous lifestyle, he felt most at home onstage. “This was the real accomplishment, the deep gratification, to go before an audience of say 3,000 and hold them for fifteen minutes,” he once wrote. “Nothing could compare or compete with this.”

The wildest Barbette story, which may or may not be true, goes like this: One night while he performed on the trapeze, a Russian sailor in the audience fell in love at first sight. According to lore, when Barbette removed his wig, the sailor was so distraught that he ended his own life then and there, shooting himself.

On a dreadful night at the Moulin Rouge in 1929, the performance portion of Barbette’s career began its decline. A billowing curtain distracted him during the show; he fell and was injured. Although he was able to recover and continue performing for a while, his body eventually began to fail him again. Years of pushing himself to the limit had taken a toll. In 1938, he was weakened by pneumonia and polio; he spent eighteen months in a hospital and was forced to learn how to walk again.

Barbette didn’t retire, though. He became a coach for other aerial performers, and moved between Hollywood, Paris, Austin, and Round Rock, serving as a production consultant for Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, as well as other companies. He also worked on musicals, including the Broadway production Around The World and the film Jumbo. During this time, he remarked to a friend how happy he was to be working: “Now my star is again in its ascendancy, and I am pleased.” Into his fifties, he left lasting impressions on those he encountered, including actor Tony Curtis. The two worked together on the 1959 film Some Like It Hot, in which Curtis’s and Jack Lemmon’s characters cross-dress so they can join an all-female band. (This plot was edgy at the time, and led a Catholic group to call the movie “morally objectionable.” Nevertheless, it was a smash hit.) Barbette’s job was to show the actors how to move like women. “I never did hear of sitting with the palms of your hands down so that you don’t flex your biceps,” Curtis later recalled. “And then there was this business of walking with your legs slightly crossed in front.”

Returning home to Texas in 1938, Barbette lived with his sister and nephew in Austin and Round Rock. He dealt with debilitating chronic pain from his decades on the trapeze. In 1969, he was the subject of a profile in The New Yorker; writer Francis Steegmuller had been working on a biography of Cocteau when he learned about Barbette’s story and became fascinated. They met in the Austin airport, and Steegmuller described the former aerialist as sharply dressed and a great conversationalist, despite being possibly in pain; his movements were “stiff and a bit jerky,” and he had a scar on his face from a fall. In the profile, Barbette said that he designed his show to be a bold mix of feminine and masculine: “I wanted an act that would be a thing of beauty—of course, it would have to be a strange beauty.” Four years after the story was published, in 1973, Barbette died at age 73 from an intentional drug overdose, likely of quaaludes.

Is Round Rock finally ready to celebrate Barbette? It wasn’t in the early 1990s, when, according to Barbette’s nephew, Charles Loving, the city rejected a proposal to erect a statue in his honor. The feeling may have been mutual; in the New Yorker piece, Barbette admitted, “I have to say that, apart from my family, everything about Austin offends me.” (It’s unclear how he felt about Round Rock specifically.) Still, a small but passionate group of local fans keeps his memory alive on Facebook and Instagram pages called We Love Barbette. One of these enthusiasts is a community volunteer named Richard Parson.

On June 30, 2021, Parson, 72, poked two small rainbow flags into the soil at the Round Rock Cemetery, where Barbette rests. The granite plate reads simply “BARBETTE” and sits alongside the graves of his mother and stepfather. Alone and with tears in his eyes, Parson was sure he felt Barbette’s presence. For Parson, himself a gay man, this moment held a surprising amount of weight. “I hadn’t even met this person, but I knew this person by spirit and that was powerful to me,” he says.

Parson learned about Barbette from his friend and colleague Christina Rudofsky, who created the Facebook page. Rudofsky nominated Barbette for the Round Rock Local Legend Award in 2015. He was one of five honorees that year. Also in 2015, the Texas Historical Commission approved a state historical marker to be placed at his grave, but it was never installed. According to Chris Florance, THC communications director, the project is still in the works. “We had hoped to receive some supplemental material from community volunteers but are proceeding without it,” Florance says. “We will complete the marker.”

Parson is also working to plan Round Rock’s first pride celebration—an event he says he knows Barbette would approve of. In October, he and Rudofsky took me to visit his grave, nestled in a bend of a dirt road that ends at the back of the cemetery. The sun had come out after a few hours of gloom, and as the clouds traveled across the sky, Parson gasped and pointed down: in addition to the rainbow flags he placed in the summer, someone had left a beaded rainbow bracelet and a seashell at Barbette’s grave site.

“I feel so connected with this Barbette story and with him as a person,” Parson told me. “I’m pleased that the world is finally going to become more acquainted with and discover our hidden gem, this hidden treasure in Round Rock called Barbette.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Round Rock