This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I’m the son of a namesake, and a namesake’s namesake son. My father was named after his father, and I was named after mine. I inherited both a handle and a ranking in the Order of Juniors and Roman Numerals. It was a double-edged deal I couldn’t refuse—I had no say in it.

Like most other namesake sons, I’ve had a lifelong love-hate affair with my name and number. There’s plenty of conflict, confusion, and pressure to perform in the old man’s image. But there can also be an enormous amount of pride, power, and privilege in carrying on your father’s name. If you can take a little kidding and overcome some of the more serious obstacles to growing up, being a namesake son can make you tougher, richer, smarter, and a better lover, as well as a better father. I’ve survived more than three decades now as a namesake, and I have to admit I wouldn’t want any other name.

In honor of Father’s Day, I decided to compare notes with other namesake sons in Texas. My sample included a U.S. senator’s son, a pawnbroker, a purchasing agent, a judge, a rancher, and a pair of identical twins given the same name with the designations “Jr. I” and “Jr. II.” I traded stories with whites, blacks, browns, rich people, poor people, Republicans, and Democrats. Each of us had experienced the bittersweet joys and pains peculiar to bearing his father’s name. But the overwhelming consensus among my fellow namesake sons was that being a namesake son is an invaluable asset. The most telling fact to come out of my interviews with namesakes was that every one of them had either passed on his name to a son already or planned to do so eventually.

What’s in a name? Nothing less than a fable of life. Every namesake must endure three crises—the dilemma of establishing an everyday identity, the struggle to be recognized as an individual, and the effort to reconcile differences with the father and develop a relationship of mutual respect. Although these are the same problems that every maturing person must solve, they are trickier for namesake sons because of the weight of carrying on their fathers’ name.

My father tried to spare me from this blessed curse. The stereotypical namesake father is a proud and vain man who seeks immortality through his same-named son. But my dear old dad, having borne my grandfather’s name with some ambivalence, wanted to call me just plain Bill. It was my mother who insisted on naming me Harry, and she got her way.

I later discovered that my “III” is something of a fraud. My father had inherited an utterly unpronounceable middle name from my grandfather, but he had dropped both the middle name and the accompanying “Jr.” shortly before I was born. By giving me no middle initial, my parents doomed me forever to writing “NMI” on forms that have a space for a middle initial. They used to joke that “NMI” stood for “not much imagination,” but it really wasn’t a laughing matter. By not giving me a middle initial my parents destroyed the legitimacy of my “III.”

My recent investigation of father-son namesakes reveals that the American namesake system is also something of a fraud. Although many people associate the tradition with Old World royalty, the popular form is actually a New World tradition. Distinctions like “the Elder” and “the Younger” were used by the ancient Romans but did not necessarily imply a father-son relationship. The Order of Juniors and Roman Numerals as we know it today began with American families in the nineteenth century. No one knows how the custom got started, but it probably had something to do with “not much imagination” on the part of American parents when it came to names. Even today, 54 per cent of American males have one of twelve first names: John, James, Charles, George, Edward, Frank, Fred, Harry, Joseph, Tom, Robert, and—most common—William.

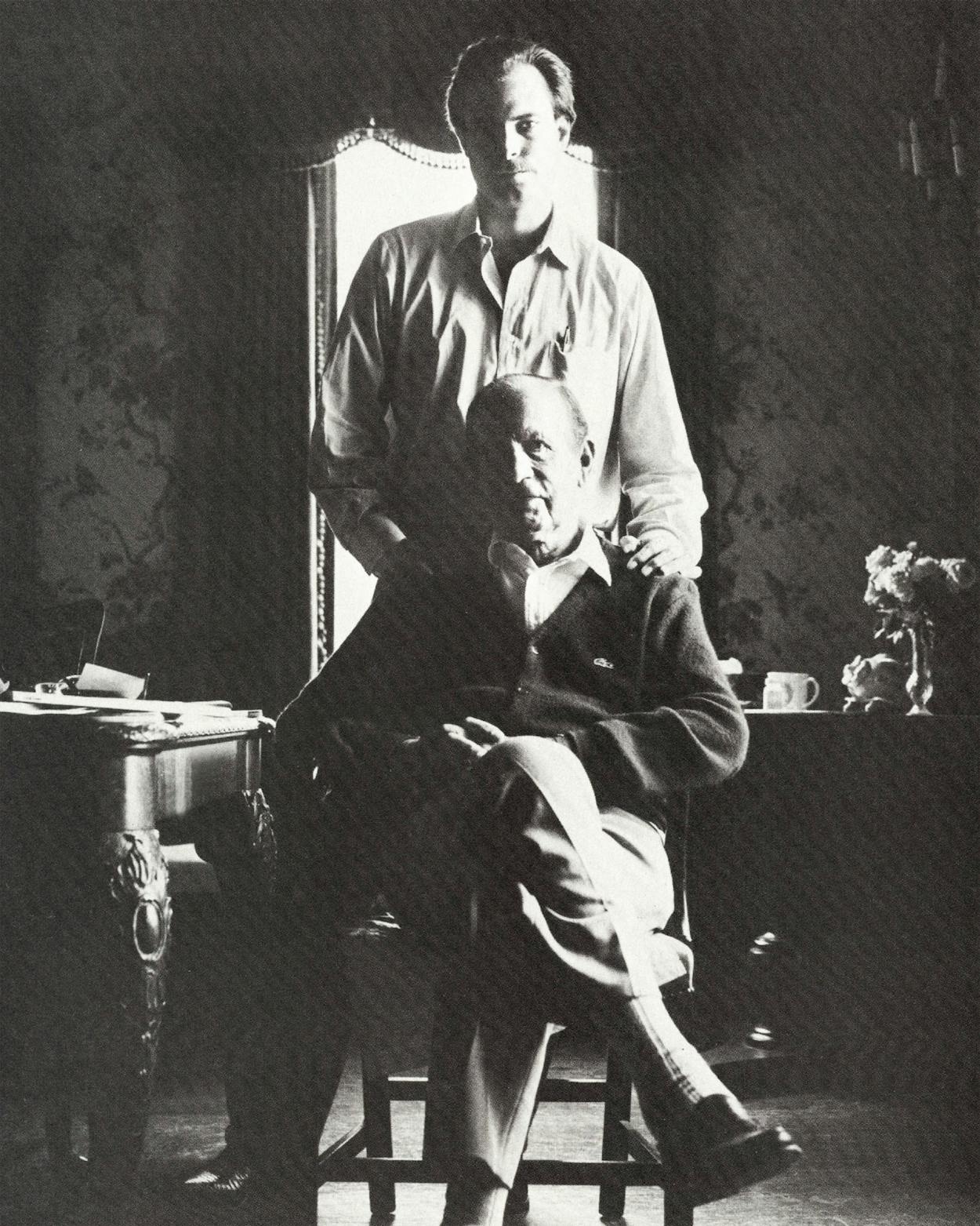

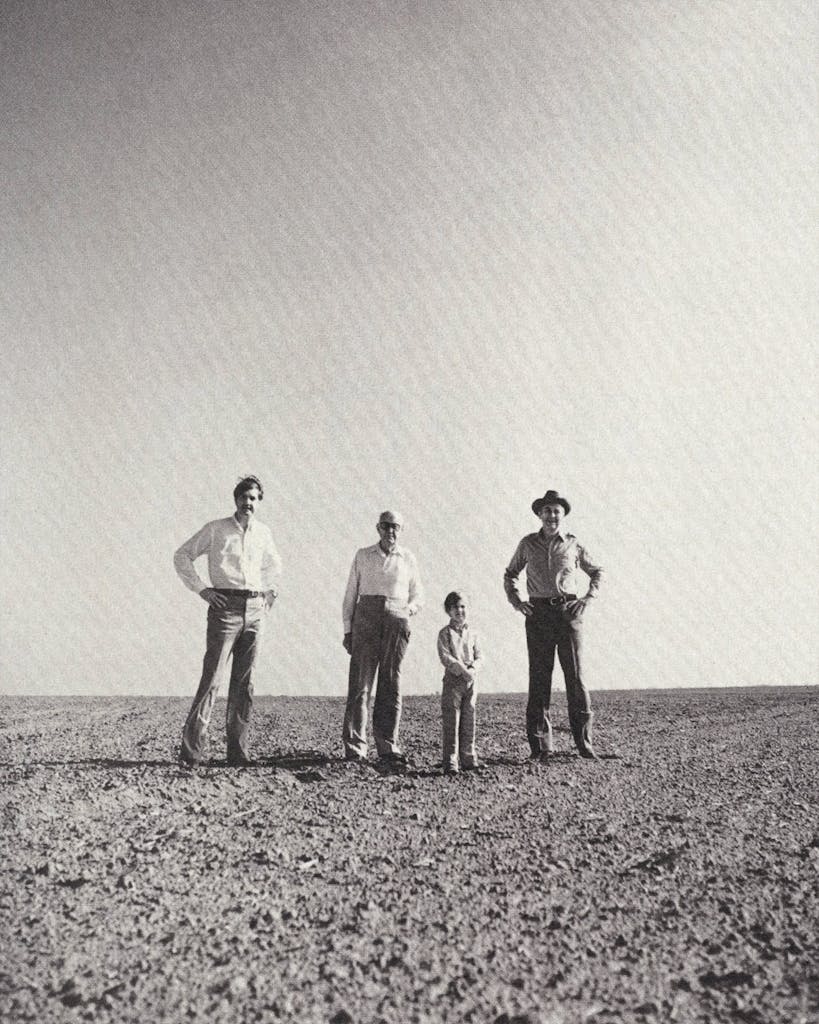

New records in namesake identity confusion are set whenever all four Lloyd M. Bentsens (pictured here at Lloyd Senior’s South Texas ranch) get together. The nicknames Big Lloyd and Little Lloyd don’t mean much then. Unless you know which Roman numeral goes with whom, you’re out of luck, as a friend of Lloyd III’s discovered when he telephoned the Bentsen family ranch one holiday. After running through several “Big”-“Little” and “Junior”-“III” combinations, the caller finally asked for Lloyd the Last. That handle worked then, but it doesn’t anymore, because the current Lloyd the Last is Lloyd III’s four-year-old son, Lloyd IV.

Purists would contend that many of the hundreds of thousands of namesakes in this country are “illegitimate.” Timothy Beard, a genealogist with the New York Public Library, says that only firstborn sons should be named after their fathers and that the Roman numeral “II” should never be used in place of “Junior.” The proper way to designate successive namesakes, he claims, is to use the Jr.-III-IV system. Beard admits, though, that there is no universally accepted namesake etiquette. (“Emily Post says something about it,” he sniffs, “but she only knows what her parents told her.”) As a result, American parents who name sons after fathers go about it as they go about most other things—freestyle. For example, the longest-running Texas namesake dynasty I found goes to the sixth generation. But the holder of this rank (who asked that his name not be mentioned) was actually given a “IV” at birth because his grandfather and great-grandfather had dropped their Roman numerals. Second place in the dynasty-longevity category went to a “V,” so Texas may have to wait a while for a “VII” whose forebears were all native-born.

Freestyle is also the way parents go about solving the first namesake crisis: what to call the child from day to day. Referring to father and son by the same name causes routine confusion. There has to be a convenient way to identify who should answer the phone, wash his face, or eat his peas. Parents attack this problem by resorting to one of three subsystems: the Big-Little Bugaboo, the Junior-Trip Trap, or the Use-the-Middle-Name Frame.

My parents innocently chose the Big-Little Bugaboo and tried to make it stick despite contradictory physical evidence. I was called Little Harry from the time I was an infant until I was a six-two college graduate who towered over Big Harry. Talk about a drag. Even in the midst of my Peter Pan I’ll-never-grow-up stage, I hated my “Little Harry” handle. It just sounded so damn twerpy. My short-lived solution was to adopt the nickname Skip. But “Skip” sounded even twerpier than “Little Harry.” I escaped being tagged Trip despite my dangerous flirtation with “Skip,” but I had to maintain a constant vigil against my father’s periodic attempts to call me by the generically similar name of “Trey.” I vowed that one day I would be known as Big Harry. The question was, When and how? Hell, maybe that’s still the question.

My parents weren’t the only problem. Since my father had dropped the “Jr.” from his name by the time I came along, people outside the family started calling us Harry Senior and Harry Junior, or in my case just Junior. That was even worse than being called Trey, Trip, or Skip. Look up the word “junior” in the dictionary; you’ll find synonyms like “youthful,” “inferior,” “subordinate.” In short, “junior” is just another word for “twerp.”

Many victims of the Junior-Trip Trap had to fight some pretty tough battles to avoid going through life with diminutive names. “I was introduced as Junior Barrera until I was a sophomore in high school, and I found it very irritating,” recalls state district judge Roy R. Barrera, Jr., of San Antonio. “Then one day I threw a fit and impressed upon my family that henceforth I would be called Roy and the nickname Junior would be dropped. It happened about the time I was taking an interest in the ladies.”

Ira Randle III used to be called Little Ira. He has no middle initial (NMI)—and that kind of bothers him, especially when people ask if NMI is his middle name. Ira III, a purchasing agent for the Houston branch of a European chemical company, says he never felt any pressure to follow in the footsteps of his father, Ira Junior, who is a foreman for U.S. Steel in Houston. But Ira III, who was called Third World by some of his friends, adds that he wants to carry on the namesake tradition. “My parents got it to ‘Third,’ ” he says. “I’d like to keep it going.” Why does he want to name a son Ira IV? “Because of the uniqueness of it,” he replies.

My father evidently didn’t like being a “Junior,” either, because he dispensed with his “Jr.” quick as he could. But that didn’t stop him from trying out new diminutives for me. His favorite was “Three,” which I always heard as a graceless “3.” Another namesake, Ira Randle III, told me he had suffered an unusual nickname: his friends called him Third World.

Much to my surprise, I did find an attractive namesake alternative in my survey—the Spanish number-based diminutives that are used by some Anglo South Texas ranching families. The most common one is “Tres” (for “Three”), but the George E. Light clan of Pearsall boasts both a Cuatro Light and a Cinco Light (George IV and George V). This approach has limitations, however, for it sounds pretentious if the bearers do not speak Spanish or live in an area where many people do. But it sure has a nice ring to it.

For all my problems with the Junior-Trip Trap and the Big-Little Bugaboo, I am grateful for having been spared the worst of parental responses to the everyday namesake crisis: the Use-the-Middle-Name Frame. The variation preferred by namesake purists is to refer to the father by his first name and to the son by their common middle name, or vice versa. But this practice merely begs the question. If you’re going to name a kid Robert E. Lee, Jr., but call him Ed, why bother to name him Robert at all?

Sometimes the son gets a middle name different from his father’s. Trammell S. Crow of Dallas has agonized long and hard over that one. The younger Trammell seems to have all the disadvantages of being a namesake and few of the advantages. His father is one of the nation’s most prominent developers. The elder Trammell Crow uses his own name as the name of his real estate and development companies. Since the younger Trammell’s middle name, Simonton, doesn’t work well as a first name, he goes by “Trammell,” as does his father. But he feels that his father’s prominence means that people will always be watching what he does. Even though he is the fourth-oldest son in the family, he has to live up to the expectations that a number one son would. He has tried using both “Jr.” and “II” to identify himself, though he is properly neither one. And he hasn’t found a convenient way to differentiate between his father’s real estate interests and his own enterprises.

Of course, any namesake subsystem is hopeless as long as the son and father answer to the same handle. Phone calls, mail, checks, bills, dry cleaning, and business deals have wound up in the hands of the wrong Harry Hurt. I’m sure my father enjoys talking to my girlfriends as much as I like taking his drilling reports and making some of his oil deals. I don’t think my father has had an easy time wearing some of my suits, but I certainly have had no difficulty spelling his name when charging items to his accounts. And we’ve both ended up at interesting parties hosted by friends we never knew we had. I just wish I’d stop getting bills for all those punk rock albums he’s been buying lately.

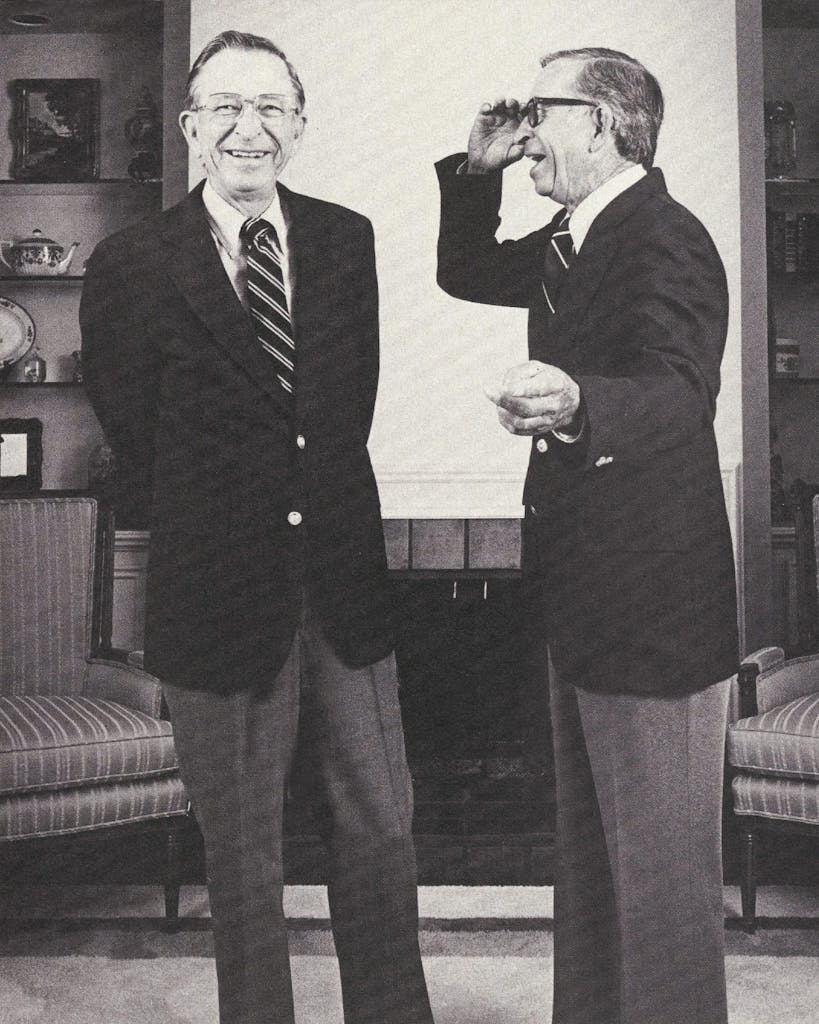

Think you’re seeing double? You are. The Dudley twins are the most unusual namesake combination I found. It all started with their late father, Henry M. Dudley, Sr. His first son, the original Henry M. Dudley, Jr., died in infancy. When Henry Senior’s wife was pregnant for the eighth time, he swore he’d name the child Henry Junior if it was a boy. His wife gave birth to twins, and he devised the “Jr. I” and “Jr. II” scheme. The twins have worked together—and been mistaken for one another—all their lives. They still answer to their childhood nicknames of Big Boy and Little Boy. The man on the left answers to “Big Boy.”

Houston twins Henry M. Dudley, Jr. I, and Henry M. Dudley, Jr. II, have elevated namesake confusion to new heights. Their late father, a restaurateur and county clerk, fathered nine children. When his first son, the original Henry M. Dudley, Jr., died in infancy, Henry Senior decided that if he had another boy, he’d make him a “Junior.” When Mrs. Dudley gave birth to twin boys, Henry Senior was undeterred; he arranged to enter “Jr. I” and “Jr. II” on the twins’ birth certificates. The only visible difference between the two boys was about half a pound in weight, so the family began calling them Big Boy and Little Boy. Those nicknames have stuck for 66 years.

Although the IRS frequently audits Junior I and Junior II on the suspicion that there must be something fishy about two tax returns with identical names, most incidents of mistaken identity have worked in their favor. Back in their Army days, every time one would get a promotion, the other would too—the commanding officer couldn’t tell them apart. And what an advantage it must be now to be able to call on an identical twin with the same name when you don’t want to face the wife and kids.

Alas, neither the Dudley twins nor any other namesake can rely on mistaken identity to get him through the most crucial namesake crisis in life: finding his true self. Every son must deal with the expectations of family members and outsiders that he will think and act like his father and follow in his daddy’s footsteps when choosing a career. But namesakes have an even tougher time with those expectations because their names suggest that they are not just their fathers’ sons but their fathers’ clones as well.

If you succeed in your father’s business, people will say you did it only because of your father’s name. If you fail, people will say you’re not the man your father was. If you do moderately well in a business other than your father’s, you will be judged a failure or, at least, unproven because you didn’t try your hand at the old man’s game. Only if you are an unassailable success in some other field can you hope to escape unfavorable comparison with your father, and then you might score points against yourself anyway for not contributing your talents to your father’s enterprise. Having your father’s name is great for opening doors, but once the door is open, you’re on your own. The catch-22 of being a namesake is that you never seem to get the chance to make it on your own, even if you want to, because you’ve got your father’s name.

For these and other reasons I thrice was on the verge of dropping my “III.” Each of the three “III” crises occurred in conjunction with a turning point in my life: embarking on a serious sports program, going off to college, and beginning a career. My father had preceded me in two of these endeavors—sports and college—but I could beat him in golf at an early age and I didn’t attend his alma mater. I chose to go into journalism rather than the oil business partly because it was not my father’s field. I assiduously avoided writing about the oil business early in my journalism career, but doing that only heightened the irony of my first book contract’s being for the biography of a Texas oilman. I felt the need to be different from—and better than—my father, to not be just another Harry Hurt. I also hated fighting off the stereotype of a “III” as a self-important rich kid.

But I finally realized that Harry Hurt III is who I am—no more and no less. Pretending I’m not a “III” because other people suppose it’s an aristocratic pretension just ain’t where it’s at. That’s their problem, not mine.

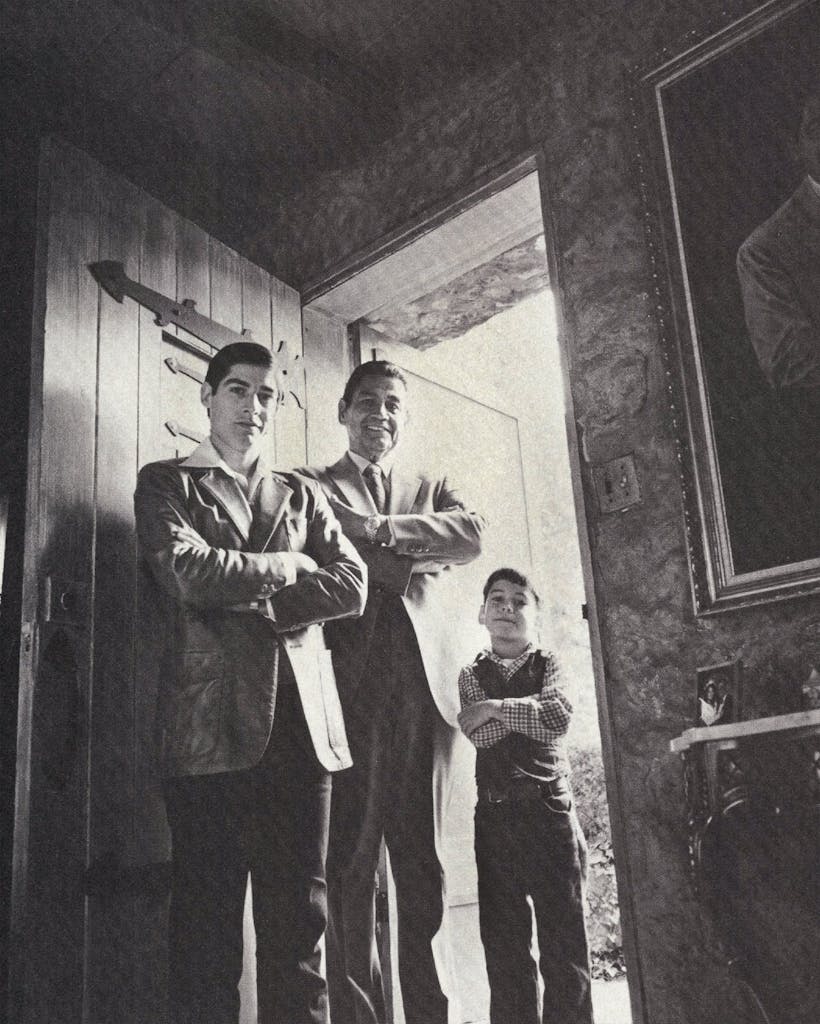

“I was introduced as Junior Barrera until I was a sophomore in high school,” recalls Judge Roy R. Barrera, Jr., “and I found it very irritating. Then one day I threw a fit and impressed upon my family that henceforth I would be called Roy and the nickname Junior would be dropped. It happened about the time I was taking an interest in the ladies.” Despite such difficulties, Roy Junior says he’s proud to carry on his father’s name. “There are a lot of Barreras in San Antonio. Being Roy Barrera makes a big difference.” Roy Junior and Roy Senior, a lawyer, call six-year-old Roy III by the nickname Little Roy.

Being a namesake son probably made me press a little harder to excel. Roy R. Barrera, Jr., regards the namesake tradition as a part of the free enterprise system because, as he puts it, “there’s always another product (your father) competing with your product (you).” I tend to agree. But I also agree with George Ray Poe, a different-middle-named son who runs a pawnshop in South Houston, that having the old man’s name makes a father and his son closer. Although I have not gone into my father’s business, he hasn’t threatened to take his name back from me, nor have I offered to return it. Even when we were most seriously at odds with each other, we had one thing in common: our name, forming a bond that always preserved some basis for understanding.

Although I’ve grown to accept and appreciate being a namesake, I have to admit that I’m not sure I want to carry on the tradition if I ever have a son. My reluctance is not because of any of the bugaboos, traps, or identity conflicts that come with being a namesake. It arises from a nominal burden of a different order: I have one of those last names that people can’t seem to resist punning. Any kid of mine, male or female, would have to endure the same sort of cheap humor I have. But somehow I just don’t think it would be fair to compound the problem by sending a son through life with everyone asking him, “What is Harry Hurt IV?”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads