The mail this morning fits into a single cardboard box, not large. Gilbert Lujan carries it out the back door of the Marfa post office, along with a couple packages, and puts it all on the rear seat of his pickup, on the right-hand side, so he can swing around and reach it from the driver’s seat. “Okay,” he says, climbing in and starting the truck. “Let’s deliver the mail.”

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, Gilbert drives a 133-mile route that takes him to some of the state’s most remote outposts, from Marfa down the vertiginous Pinto Canyon Road to the hamlets of Ruidosa and Candelaria, snugged up against the Rio Grande, and then back to Marfa. These small towns along the river, each home to just a few dozen people, don’t have their own post offices. The postal service serves communities like these by awarding five-year contracts for folks like Gilbert to deliver mail on specific routes. Gilbert, who is 71, took on this route seven years ago after the previous carrier suffered a heart attack. “I thought I’d just finish out the year and a half on his contract,” Gilbert says. “But when it was up, I reapplied and got it.”

Gilbert’s mustache is still dark, though his slicked-back hair is silvering. He wears metal-framed eyeglasses, and hanging at his hip is an assistant chief’s badge for the Marfa Volunteer Fire Department. On our way out of town, he stops at the grocery. “Let me pick up some advertising flyers, or those women in Candelaria will get mad,” he says. “I take a stack, and everyone gets one or two. Wintertime, they want the paper just to start the fire on the woodstove.”

At 8:10 a.m., we’re on the road, wheeling past a rangeland gone Oz green from the summer monsoons. The country turns into big rolling hills, the dome of Chinati Peak looming beyond like a great stony moon. A vulture, wings akimbo, sits atop a fencepost. The talk on the local NPR station is about asylum seekers and immigration. Gilbert’s gold-toned 2006 Lincoln truck is the only vehicle on the road. He drives alone and without cell service for nearly the entire trip. Rarely, he encounters walkers—undocumented immigrants making their way through this thorny, rocky, and unforgiving landscape. “I give them water or something to eat if I have something,” he says. “I’ve even had guys say, ‘Call the Border Patrol, come pick me up,’ because they’re dying. But I never had any trouble.”

Chocolate daisies fill the bar ditches on either side of the road. A red-tailed hawk rests on a juniper. Thirty-two miles into the drive, the pavement gives way to dirt, and, a few miles later, across a cattle guard at the crest of a hill, the grassy rangeland abruptly ends, and the expanse of Pinto Canyon drops into view. The road is crazy steep and narrow in spots. No guardrails here, just a jarringly rock-pocked dirt road winding down the mountain to the canyon floor miles below. Chinati Peak towers to the left. Spindly ocotillos stiffly waggle their many arms. A roadrunner streaks past. Rocks upon rocks upon rocks, red, pink, and chalky white. Hills upon hills upon hills. Other than fences and the scars of rough ranch roads, there is little evidence of human habitation. Gilbert eases the Lincoln along, chattering all the while, unfazed by the dangerous drop-offs and the rocks and cacti. We never get above 15 miles per hour. “I take it easy,” he says. “It’s better than trying to rush.”

Gilbert has worked nearly all his life. He was born in a house in Marfa, in 1948, the oldest of three brothers. Their parents, Gilberto and Gloria, were from Marfa and Shafter. As a child, Gilbert helped his mother clean Border Patrol offices and the bank after hours. Later, he learned car bodywork from his dad. As a young man, he left for El Paso, where he ironed 150 pairs of pants a day at a Farah clothing factory, but he left after six months. “I didn’t like it,” he says. “I was spending every weekend in Marfa anyway, so I came home.” Over the years, Gilbert has run his own body shop, driven long-haul trucks, and, for 22 years, worked on a county crew that maintained parks and county roads, including the very one he now drives. These days he works part-time for a ranch, feeding cows and running heavy equipment. And he drives the mail.

On the bottom of the canyon the landscape changes. Gilbert bumps across a dry creek, a shady spot with cottonwood trees, stubby oaks, and grass. “There’s usually water here,” he says. High water is the only thing that will turn him back, which has happened four or five times over the past seven years. When this occurs, he goes out the following day to try again. The road is tough on vehicles. Gilbert carries water and radiator fluid on every trip, since the rocks and holes in the road mess up ball joints, radiators, tires. “I’ve had five blowouts,” he says. “I put brand-new tires on, and the first thing, I had a flat the following day. Three days later, another. I told the guy, ‘Are these ten-ply? Because they sure enough are not doing the job.’ ”

The road becomes wider, the land flattens. Two hours after we began and about fifty miles from Marfa, he makes his first mail stop: a metal building with earth-moving equipment out front and, as a sign of optimistic capitalism at play in this vast, empty-seeming place, an application to sell alcohol, hanging on a fence. Gilbert reaches into his box, pulls out a catalog, and walks it to the mailbox. There’s no one around.

Ahead on the road are the small adobes and trailers of Candelaria. A quarter mile out, Gilbert lays on the horn. “Lets them know I’m here,” he says.

Ten minutes later, here’s Ruidosa and signs of civilization. The dirt Pinto Canyon Road T-bones the paved FM 170, and the Rio Grande’s not far ahead, hidden by salt cedar and mesquite. Gilbert offers information about the properties we pass. This one has a recently planted pecan orchard, irrigated by the river. There’s a house on the rimrock that’s allegedly made of glass. This lady over here lives alone; Gilbert worries that she doesn’t have good access to water. He points out a large adobe ruin on a low rise above an arroyo. What do you think that was, looking out over the valley and the river? A fort outpost? Could be.

Gilbert pulls over at appointed spots, slides mail into mailboxes, and waits a few beats in case someone comes out and needs him. So far, no one does. The river appears, bending companionably with the road. There are stands of tall, reedy grass on the Mexican side, deeply green. A dozen black ducks ride the riffles of the water. The river’s surface reflects the overhead passage of the velvet-hulled clouds, nationless and unboundaried. To the left are the rooftops of San Antonio del Bravo, Chihuahua, and, ahead on the road, the small adobes and trailers of Candelaria. A quarter mile out, Gilbert lays on the horn. “Lets them know I’m here,” he says. It’s 11:04 a.m.

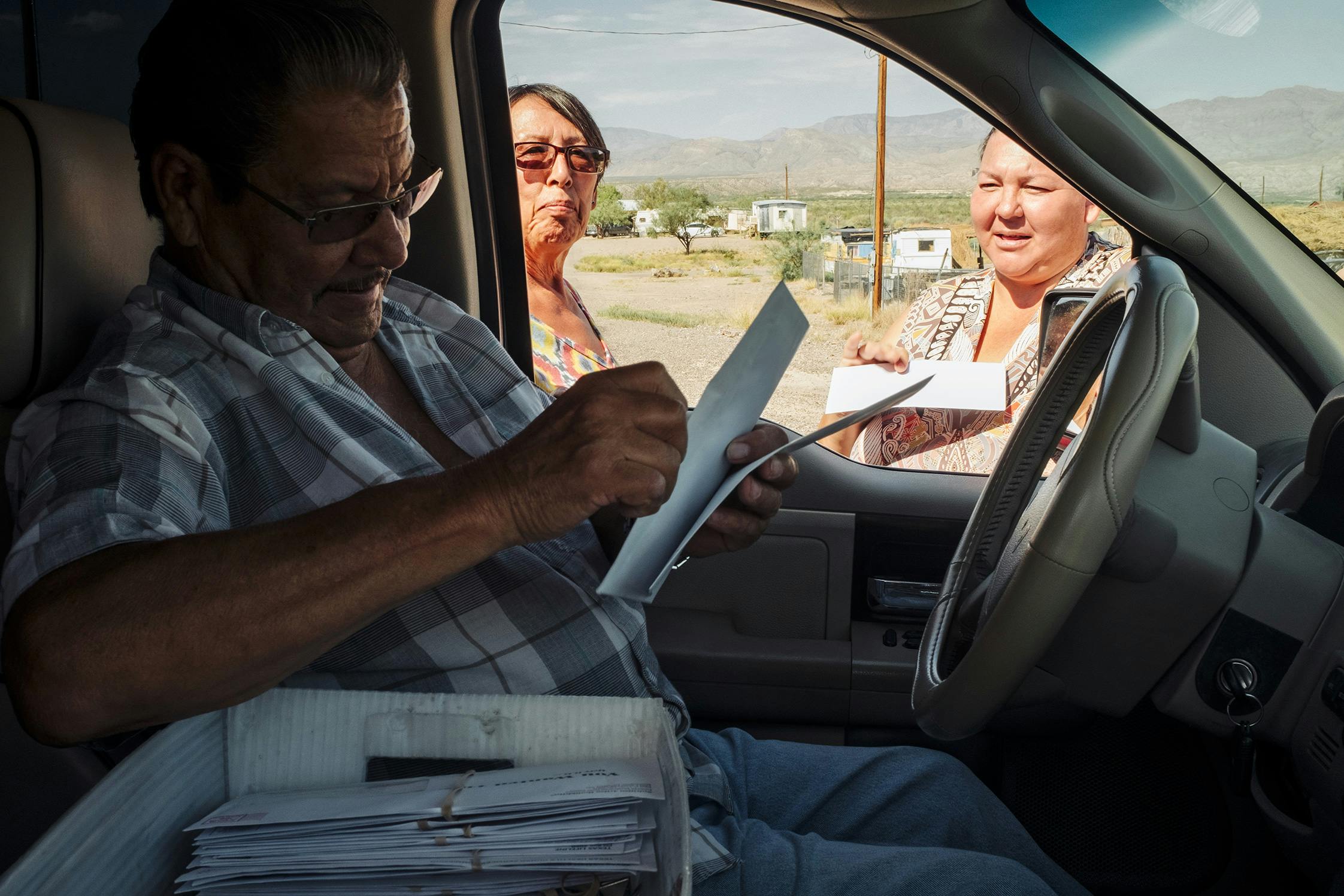

He pulls onto a dirt side road and waits outside a chain-link fence. A woman wiping her hands on a black apron exits her residence, made up of two small camping trailers that are dubiously conjoined. She stands at Gilbert’s window while they chat in Spanish. She smells of pancakes and syrup. He flips through the mail and hands her a couple items. He holds up an envelope with a Candelaria address but without a name he recognizes. Does she know this person? No. No. The woman gives Gilbert a bill from Big Bend Telephone, and he pulls out a clipboard with blank money orders. He carefully makes out the order with a ballpoint pen. This takes a little time. A dove calls woo whoo woo. Plastic toys bake in the dirt yard. Gilbert uses his phone’s calculator to add up the bill, along with the cost of the money order and stamp. She hands him the total, which he puts in the bill’s envelope and sets aside. He’ll use the cash to buy the money order at the post office in Marfa later today, then put it in her bill and mail it for her. She then gives him a $20 bill and a grocery list written in childish handwriting: un galon de leche, tres galones de jugo, Downy. A discussion ensues. Gilbert likes a canned alcoholic drink sold in Mexico, and the woman agrees to bring him some of those when he comes again on Friday, plus a watermelon or two. He returns the $20; they’ll settle the difference later. Do other mail carriers do this sort of thing? I ask, as Gilbert pulls away. “I don’t have no idea,” he says.

He idles the truck at a spot on the paved road. If Candelaria were representative of all the border, it would be a place populated solely by women, little children, and a few itchy dogs. A woman approaches with a half-pint terrier trotting at her heels. Another woman emerges from a travel trailer, and a third woman also arrives, holding a girl’s hand and trailed by two smaller girls clutching dolls. They form a loose line at his window. There’s a round of small talk, and he hands each of them grocery store flyers. He scans a package and gives it to its recipient. He holds up a notebook. “I write down every package I deliver, to keep track,” he says.

Patiently, Gilbert writes out more money orders for the phone company, totals the charges, makes change from a bag of small bills and coins, and puts each woman’s cash in its respective envelope. A boy runs up, opens the truck’s back door, takes two bottles of laundry detergent, and hustles them into a low adobe house. Here’s a $5 bill for more detergent. Here’s a food stamp card; the woman promises to text Gilbert her shopping list.

Gilbert forbids big grocery orders, ever since someone started sending him lists that ran into hundreds of dollars, and he’s talked about ending the practice altogether. It sometimes takes him an hour and a half to shop for the people on the route, he says, “more time than I take for myself. They usually want the basics: milk, cereal, meat, flour, chicken when it’s on sale. I tell them, ‘Don’t text me on Sundays.’ I want to relax and not go to the store.”

Post Modern

In the early 1900s, Candelaria did, in fact, have its own post office—and a school, a cotton gin, and a population of more than five hundred people, making it a lively farming community.

Gilbert moves to a third stop, in front of Candelaria’s tiny and lovely church, and takes care of yet more money orders, hands out letters, asks again if anyone knows this woman who has mail with a Candelaria address but a name he does not recognize. No, no. After the last letters are delivered, Gilbert organizes the money orders, the envelopes, the grocery lists, the outgoing mail. He produces a sheet of stamps decorated with Disney villains and applies them where appropriate. “I have to be back by 2:30 or so,” he says. “It takes me half an hour to buy the money orders and get them sent off. I have to get it done before the Marfa post office closes.”

Does he ever wonder what’s in those letters with the jail ID number carefully printed on the envelope? Does he ever think about what’s in the padded package from Odessa or the serious-looking business envelope? Does he think about his role in all this communication and information going hundreds or thousands of miles from one person to another at what can seem like the frontier of the known universe, how he’s the man who makes that communication possible, the conduit who makes that happen? He gives me a quick look, a squint, really, and swats his hand in the air. “Nah,” he says. “I don’t.”

And then we’re bound for home. Gilbert’s truck leaves the paved road for the dirt road once again. Past the deep slice of canyon where Pancho Villa might’ve hidden gold. Past the cattle gathered at a water tank. Past an oncoming silver-colored pickup, the only traffic we’ve encountered, whose driver, though reduced to a silhouette in the light, somehow radiates great tiredness and resignation in his slouch and fleeting hi sign. On these long drives, Gilbert has the radio for company, though once in a while he gets lost in his thoughts. “Sometimes I think about selling my little acreage and taking my wife to Hawaii,” he says after a while. “I wonder about that.” His three-days-per-week route is strict, however. He and his wife make occasional weekend trips to San Antonio, but he can’t take real time off unless he finds a substitute who’s willing to go through fingerprinting and a background check and willing to subject a vehicle to the abuse of this road. That person hasn’t appeared yet. “It’s okay,” says Gilbert. “If I’m working, I’m doing good. If I stopped working, I’d just die.”

We roll along on that rocky road, under those immigrant clouds. We roll along, a little speck of a truck climbing a canyon, and with us a cardboard box, its envelopes full of unseen desires and unknown requests, declarations, statements, facts, and money, all of it being sent away, going someplace, definitely.

This article originally appeared in the November issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Man of Letters.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Big Bend