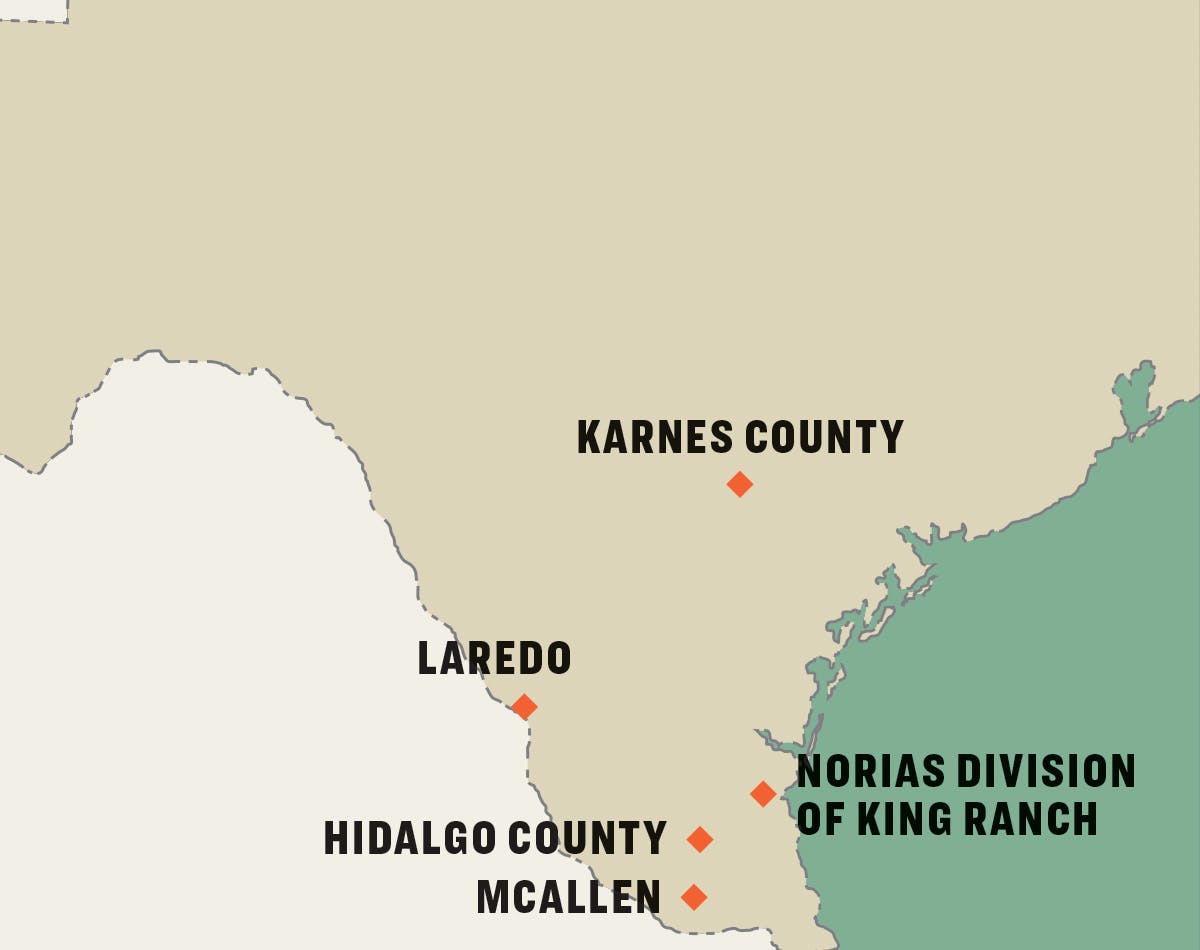

The graves of Jesus Bazán and his son-in-law Antonio Longoria are located in a small family cemetery in northwestern Hidalgo County, deep in South Texas, close to the Mexican border. There is a modern farm-to-market road nearby, but the graves were dug many years ago at the edge of an older, unpaved road no longer in use. Jesus Bazán was 67 when he died on a September day in 1915. His son-in-law was 48. He died the same day. Their tombstones give no account about what happened to them, only the word “Murió”—“Died.” But no doubt there were friends and family members who would have preferred to see another word carved there: “Asesinado”—“Murdered.”

The manner of their deaths was nothing special, if you take into account the way things were during the terror years of 1915 and 1916 in the lower Rio Grande Valley. Bazán and Longoria were traveling down the road when a group of Texas Rangers under Captain H. L. Ransom came along and shot them off their horses. One account says the Rangers had a list and one of the names on it was Longoria. The fact that Antonio was the wrong Longoria, or that Bazán had been vouched for as a law-abiding citizen by a nearby Anglo rancher, meant little to Ransom. He and his men rode away, leaving Bazán and Longoria dead on the ground under the piercing South Texas sun. The bodies stayed there, unburied. The families of the murdered men fled their homes, convinced they would be killed as well if they tried to retrieve their loved ones. Tejanos driving their wagons down the road steered around the bodies, fearful that a show of human sympathy would mean, to the Rangers, proof of conspiracy. After several days, nearby ranchers, disturbed by the stench of decomposition, finally ventured out to bury them.

Bazán’s and Longoria’s names are recorded, their bodies buried, but there has never been anything close to a full accounting of the hundreds, and more likely thousands, of people who were killed along the border and left in the chaparral or dumped into resacas during the violence that was sparked by the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920.

In Texas, this was a war of raids and reprisals concentrated mostly through the Rio Grande Valley, the same trouble spot previously best known as the Nueces Strip. “Valley” is an unconvincing word for a thorny tropical expanse of country without any hills or mountains in sight, but nevertheless, that’s what it’s called.

The trouble had been seething for at least a century, since the arrival of the first Anglo colonists. It had erupted into open conflict in 1859 when an aggrieved Mexican landowner named Juan Cortina led seventy men in a vengeance raid on Brownsville. The violence flared up again during the turmoil of the Civil War, and in 1891, after a Texas newspaper publisher named Catarino Garza, a veteran of gunfights and court battles with Texas Rangers, raised an army and initiated a brief cross-border war whose goal was to unseat Mexican president Porfirio Díaz. And then, in 1901, there was the case of Gregorio Cortez, a former vaquero farming in Karnes County. The local sheriff, who was looking for a “medium-size Mexican” wanted for horse theft, approached Cortez and his brother. There was a tense, garbled interrogation in Spanish that ended when the sheriff shot the brother. Cortez in turn killed the sheriff, took flight, and evaded hundreds of law officers throughout Central and South Texas for ten days before he was finally captured. His artful elusiveness, combined with the conviction that he was innocent, turned him into an instant folk hero for Tejanos trying to survive in an Anglo universe of tightening injustice and casual suspicion.

Things got worse for Tejanos when the railroads reached the Rio Grande Valley in 1904, opening the region up to commercial agriculture and delivering by special excursion trains an epic population surge of Anglo farmers and businessmen. A Houston Chronicle writer exulted in the new world that the railroads were creating “through the range of the longhorn, across the ranches, over the dominion of the rattler and horned frog.” The population of the “Magic Valley,” as the promoters called this part of South Texas, doubled in ten years. Land prices soared; ranches were irrigated and subdivided into farms.

It was not just the dominion of the rattler and horned frog that was coming to an end but also the deep-rooted ranching culture that Tejanos had invented. The promotional literature of one of the new development companies put it succinctly: “The golden glow of the brush fires against the night sky, where land is being cleared for cultivation, truly typifies the passing of the old civilization and the coming of the new.”

This new civilization meant higher taxes to go with the higher land prices, forcing small ranchers to sell out to developers and turning vaqueros into field workers. And many cash-poor Tejanos found out that owning land was different from keeping it, since it required money they didn’t have to uphold a claim in court against a rich and well-connected claimant. “I told him to pack up his doll rags and piss on the fire” is the way one encroacher described ordering away the Tejano he considered to be squatting on his land.

Following on the heels of this huge cultural shift came destabilizing shock waves from a climactic power struggle across the border. Porfirio Díaz had been the ironfisted Mexican president on and off since 1876. When he was challenged in 1909 by a reformist candidate, Francisco Madero, he had him arrested for sedition. Madero managed to escape to San Antonio. There, in a house on Santa Rosa Avenue, he published a manifesto—“Plan de San Luis Potosí”—that ignited the Mexican Revolution. The Plan declared that all Mexico should arise at the same hour of the same day “to eject from power the audacious usurpers whose only title of legality involves a scandalous and immoral fraud.”

This call to action sparked a complex, fragmented uprising throughout Mexico as rebel armies led by leaders such as Francisco “Pancho” Villa and Emiliano Zapata helped bring Madero to power in 1911. “Madero has unleashed a tiger!” Porfirio Díaz grumbled on his way to exile in Paris. “Now let us see if he can control it!”

He couldn’t, and was dead at the age of 39 a little more than a year later, assassinated after being deposed in a coup by General Victoriano Huerta, the counterrevolutionary dictator whose oppressive rule was known as “La Mano Dura” (“the Hard Hand”). But by 1914 Huerta too was gone, replaced by Venustiano Carranza, the head of one of the many revolutionary armies fighting for power in the ever-splintering Mexican Revolution.

The revolution certainly didn’t bump to a stop at the Rio Grande. The U.S. side of the river was populated now not just with Tejanos whose lands and jobs were disappearing under the flood of Anglo immigration but also with a steady flow of Mexican refugees desperate to escape the violence in their country. The sense of an impending reckoning was kept alive by influential publications like Regeneración, an anarchist newspaper that had once been headquartered in San Antonio and was spearheaded by two brothers named Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón. By the time the civil war in Mexico had reached its full chaotic force, the Flores Magón brothers were in exile in Los Angeles, but the activist call to arms of their newspaper and the political organization they had founded, the Partido Liberal Mexicano, still echoed along the borderlands of Texas and Mexico.

One particularly fervent reader of Regeneración, and a close friend and correspondent of Ricardo Flores Magón, was an activist and woman of letters named Sara Estela Ramírez. Born in Mexico, she had lived in Laredo since she was seventeen, where she became a teacher and then a widely read contributor to newspapers such as El Demócrata Fronterizo and La Crónica.

“Revolution approaches!” Ricardo Flores Magón notified the Mexican and Mexican American women who read his newspaper, in an editorial titled “A La Mujer.” Flores Magón sported a modern-trending Salvador Dalí mustache, but his instructions to women had a past-century patriarchal ring. While acknowledging that they were sisters in the struggle (“If men are slaves, you are too”), he told them that their duty was “to help man; to be there to encourage him when he vacillates; stand by his side when he suffers; to lighten his sorrow; to laugh and to sing with him when victory smiles.”

Sara Estela Ramírez never got to read Flores Magón’s lecture about how revolutionary women should behave. By the time it was published, in September 1910, she had been dead a month. Some unknown illness claimed her at the age of 29. But she had already issued a feminist directive, her own version in poetry of “A La Mujer.” Its title (“¡Surge!”) translates in English as “Rise Up!”

Rise up! Rise up to life, to activity, to the beauty of truly living; but rise up radiant and powerful, beautiful with qualities, splendid with virtues, strong with energies.

When she died, Ramírez was eulogized in La Crónica, one of the newspapers she had contributed to, as “La Musa Texana.” La Crónica was published in Laredo and was a family enterprise, operated by Nicasio Idár—a former vaquero on the King Ranch—and his children Jovita, Clemente, and Eduardo. Jovita, who had written Sara Estela Ramírez’s obituary, began her career as a teacher, but the conditions she encountered in Laredo’s segregated Mexican American schools sparked her outrage and animated her investigative instincts. She joined her family’s newspaper, whose motto was “We work for the progress and the industrial, moral, and intellectual development of the Mexican inhabitants of Texas,” and reported from all over the Rio Grande Valley, covering the lynchings and land thefts and other crimes against Tejanos that were likely to go unremarked in Anglo publications.

In 1911, Nicasio Idár organized a conference in Laredo called the Primer Congreso Mexicanista, a major civil rights gathering that drew participants from all over Texas and Mexico. Among the items on the agenda were women’s rights, and after the congress, Jovita Idár became the first president of La Liga Feminil Mexicanista (League of Mexican Women).

Ricardo Flores Magón, whose idea of a woman’s role in the struggle was to shore up the vacillating will of her man, might not have known quite what to make of the take-charge attitude of someone like Jovita Idár, who wrote articles for La Crónica with titles such as “Debemos Trabajar” (“We Should Work”). When the Mexican Revolution broke out, she crossed the border to Nuevo Laredo to volunteer as a combat nurse for Carranza’s forces. In 1913, back on the Texas side of the border, she made enemies when she published an editorial in the newspaper El Progreso denouncing President Wilson’s intervention in Mexico. The Texas Rangers were sent to close down the paper, but when they got there and encountered Jovita Idár standing in the doorway with her arms crossed, refusing to budge and refusing to let them in, they decided they’d better come back another day.

“Things did not look right,” one Tejano resident remembered of those tremulous years in Texas. “Something queerly fantastic, unnatural, seemed to be hovering over the Valley and along the river front.”

In January 1915, Basilio Ramos, a 24-year-old Mexican citizen and former employee at a beer company in the South Texas town of San Diego, was apprehended by a deputy sheriff in McAllen, deep in the Valley. In his pockets were several letters of introduction to various activists in the Rio Grande Valley from prominent insurrectionists in Mexico, including one that said, “I am convinced his testicles are in the right place.”

But the document that mattered, whose discovery ignited the revolutionary tinder along the Rio Grande, was a manifesto that would be known as the “Plan of San Diego.” It was the blueprint for an apocalyptic uprising against “the Yankee tyranny which has held us in iniquitous slavery since remote times.” The plan called for the independence of all five U.S. states that had bordered the original Republic of Mexico, states that would then be formed into a new independent republic that might at some future date—“if it be thought expedient”—be annexed to Mexico. The land taken from the Indians would be returned. This new republic would offer African Americans freedom and equality and help them seize neighboring American states so that they could create their own independent nation. It would even “grant them a banner, which they themselves shall be permitted to select.”

The Plan of San Diego might have been dismissed as fancifully far-reaching if it had not been for, among other incendiary passages, Article 7, which stated as clearly as anything could be stated: “Every North American over sixteen years of age shall be put to death; and only the aged men, the women, and the children shall be respected; and on no account shall the traitors to our race be spared or respected.” Another such document surfaced the next month, decrying the gringos’ “hatred of races which closes the doors to schools, hotels, theaters and all public establishments to the Mexican, black and yellow, and divides the railroads and all public meeting places into areas where the savage ‘white skins’ meet and constitute a superior class.” This document promised not just to end segregation but to create “Universal Love,” in part by seizing lands from capitalist overlords and delivering them, and the railroads that crossed them, into the collective keeping of the proletarians.

It’s hard to know how direct an influence these manifestos had on the events that followed, since the storm of violence didn’t really break until that summer, when groups of sediciosos—as the insurgents came to be called—began a series of sporadic raids on farms and ranches and burned a railroad trestle near McAllen. At first it seemed more like freelance banditry, but the sense of there being at least an attempt at coordination came with the publication of a third manifesto in late August, grandly claiming that the sediciosos maintained a “General Headquarters” in San Antonio. It was signed by a fifty-year-old former deputy sheriff named Luis de la Rosa (“First Chief of Operations”) and by Aniceto Pizaña (“Chief of the General Staff”), a rancher, a poet of outraged political verses, and a fervent follower of the Flores Magón brothers. The authors declared that the territory to be seized from the United States would be called, with blazing irony, the Republic of Texas.

“The moment has arrived,” the document promised. By then, there had already been a number of targeted attacks, including the assassinations of a rancher named A. L. Austin and his grown son, Charles. Austin was the head of the Sebastian Law and Order League and an abusive overseer of the Tejanos who worked on his ranch. “Every time he kicked a Mexican,” a local deputy sheriff recalled, “he made an unrelenting enemy.” He and Charles were taken from their house and shot dead in a nearby field. Austin’s wife, Nellie, related with chilling precision what she saw after the marauders left the house: “I first went to my husband and found two bullet holes in his back one on each side near his spinal column. . . . My husband was not quite dead but died in a few minutes thereafter. I then proceeded to my son Charles who was lying a few feet from his father; I found his face in a large pool of blood and saw that he was shot in the mouth, neck and in the back of the head and dead when I reached him.”

A few days later there was a full-scale attack on the King Ranch. It happened at Norias, one of the five divisions of the ranch, which by then commanded a great swath of the South Texas map and was the size of an inconspicuous country. (Ten years later, under the stewardship of Richard King’s widow, Henrietta, and her son-in-law Robert Kleberg, it would vault in size to well over a million acres.) The manager of Norias was Caesar Kleberg, Robert’s cousin. He was in Brownsville when he got word that an attack might be brewing, and he sent out a call for help. Army troops, deputies, and Rangers rushed by train to the Norias ranch house. The Rangers were out scouting when a group of sediciosos charged the house with Mauser rifles. Inside were only sixteen defenders—soldiers, ranch employees, and a few civilians from Brownsville who had come along hoping to pitch into a fight.

A few days later there was a full-scale attack on the King Ranch. It happened at Norias, one of the five divisions of the ranch, which by then commanded a great swath of the South Texas map and was the size of an inconspicuous country. (Ten years later, under the stewardship of Richard King’s widow, Henrietta, and her son-in-law Robert Kleberg, it would vault in size to well over a million acres.) The manager of Norias was Caesar Kleberg, Robert’s cousin. He was in Brownsville when he got word that an attack might be brewing, and he sent out a call for help. Army troops, deputies, and Rangers rushed by train to the Norias ranch house. The Rangers were out scouting when a group of sediciosos charged the house with Mauser rifles. Inside were only sixteen defenders—soldiers, ranch employees, and a few civilians from Brownsville who had come along hoping to pitch into a fight.

One of the civilians was an immigration inspector named D. P. Gay Jr., who later set down a florid account of the desperate two-and-a-half-hour battle, during which the defenders saw four men wounded but finally drove off the sediciosos after killing at least five. “Knowing there were 75 or 80 bandits,” Gay wrote, “I could not help from thinking of those immortals, Travis, Bowie, and Crockett and their memoriable [sic] fight at the Alamo, when a hundred and eighty red-blooded Americans fought about five thousand greasers.”

But nothing as conclusive or inspiring as the Alamo ever took place in the grubby race war that had erupted in South Texas. There were only raids, bushwhackings, casual executions, and showcase atrocities like the one that befell a U.S. Army private named Richard Johnson. He was captured by rebels during an attack on the town of Progreso on the north bank of the Rio Grande and taken across the river. The next time his fellow soldiers saw him, his head, stuck on a pole, was staring back at the United States of America.

Read more: This ‘Big Wonderful Thing’ excerpt recounts how the Republic of Texas took its fight against Native Americans to the heart of Comanchería.

In late September 1915, a party of sediciosos attacked the ranch of a man named James Ballí McAllen, an Irish immigrant who had married into a Tejano family with roots in Texas going back to a Spanish land grant they had received in 1799. When the assault came, only McAllen and his cook were home. Her name was Doña María de Agras, a former soldadera who had fought with Madero against Porfirio Díaz. With McAllen firing and Agras loading his handcrafted Greener shotgun and Winchester rifles, they killed two of the attackers and fatally wounded at least one other, and somehow managed to avoid being hit themselves by any of the five hundred bullets that aerated the house. A Ranger captain who arrived at the scene after the battle was particularly impressed by Doña María’s coolness under fire: “Fresh from the revolutions in her native land, she was inured to the sight of bloodshed. During the attack on the ranch, she had no intention of remaining a passive spectator.”

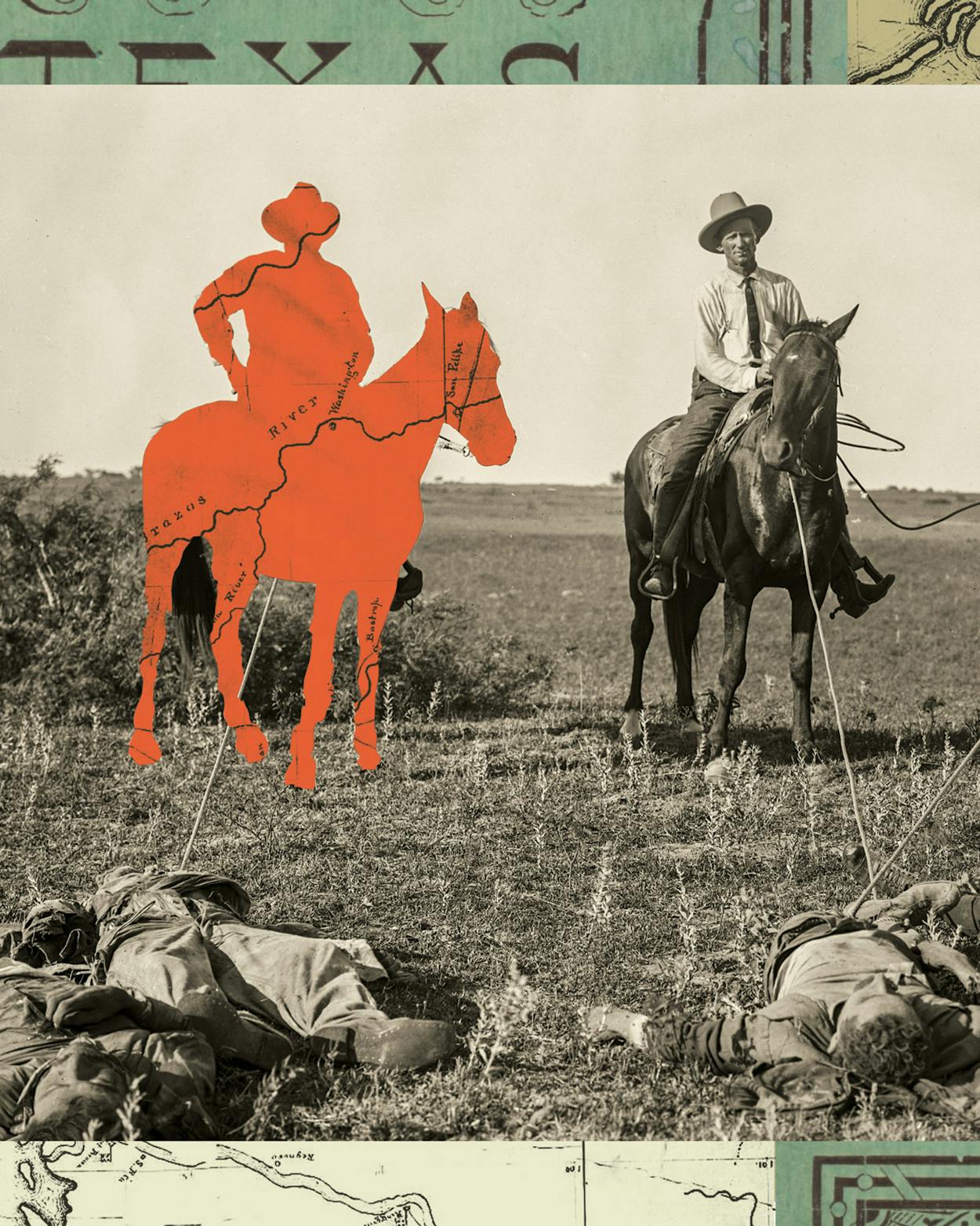

It was the search for the perpetrators of the McAllen ranch raid that led to the Rangers’ mistaken—and indifferent—killing of Jesus Bazán and Antonio Longoria. Their deaths were part of a rampage of retribution, chronicled in gloating photographs that have considerably darkened the already complicated reputation of the Texas Rangers. In the most famous of these photos, taken after the Norias raid, three Rangers pose on horseback, having roped the dead bodies of four sediciosos that they seem to be planning to drag through a brushy pasture. In another, a Ranger has plopped a sombrero onto a skull and is holding it out with one hand as if contemplating the fate of Yorick while he points a pistol at its eye socket.

The atrocities were certainly not all on the Anglo side, but the legacy of the uprising was tighter oppression against Mexican Americans and a renewed and codified attitude of superiority on the part of whites. In the triumphant hindsight of a Hidalgo County deputy sheriff, the white race “had fought for all it had ever gained, and it had gained much since its trek from the shores of Albion to the chaparral fringes of the Rio Grande, therefore fighting was not new to it as attested by the gruesome skeletons found even at this late day, twenty years after, in the wilderness, lying in neatly arranged rows, side by side, each with a trim, round hole in the forehead squarely between the empty eye-sockets—‘Brands’ of the Texas [R]angers’ ‘irons,’ the never-failing 45-Colts.”

J. T. Canales, a Brownsville lawyer and the only Tejano member of the state legislature, introduced a bill in 1919 whose intention was to starve the Rangers of state resources. The bill ended up being sandbagged, but it led to a joint House and Senate investigation into Ranger conduct, for which Canales served as the prosecuting attorney. He did his job fervently but skittishly, perhaps because he was convinced that at any moment he would be assassinated by Frank Hamer, a particularly intimidating six-foot-three-inch slab of Texas Ranger who would later lead the manhunt and ambush that killed Bonnie and Clyde.

Canales had reason to be worried. “You are . . . complaining,” he claimed Hamer told him, “to the Governor and the Adjutant General about the Rangers, and I am going to tell you if you don’t stop that you are going to get hurt.”

As it turned out, Canales lived to be 99 years old, not dying until 1976. The investigation he launched brought modest reforms. The Texas Rangers were not exactly punished for their exterminating missions along the border, but the hearings brought at least some of that behavior into public view. “These young men, hot blooded young fellows without much education,” one witness told the committee, “men who are willing to go out and risk their lives for forty, fifty, or sixty dollars a month and lead the kind of lives they do, are not the type of men you want to entrust the lives and properties of the citizens to without throwing around them some safeguard.”

Stephen Harrigan will be a featured speaker at EDGE: The Texas Monthly Festival in Dallas November 8-10. For tickets, visit edge.texasmonthly.com.

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The New Texas History.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Stephen Harrigan