Today, expensive homes dot the hills of Austin’s western fringe. But there was a time, not so long ago, when respectable townspeople avoided the highlands just outside the city. There, along the Balcones Escarpment, the geological fault zone marking the eastern edge of the Edwards Plateau, a reclusive folk known as cedar choppers lived hard and free on the rugged terrain, and polite company kept its distance.

Austin native Ken Roberts was ten or eleven the first time he encountered the children of cedar choppers, at the low-water crossing of the Colorado River below the Lake Austin dam sometime in the mid-fifties. “I remember how different from us they looked,” he writes in his 2018 book The Cedar Choppers: Life on the Edge of Nothing (Texas A&M University Press). “They were barefoot, their pants were too short, their shirts ragged. These were not kids you would see in Austin.”

The boys set Roberts on edge, and when his friend Dudley taunted them, one of them pulled out a club. Roberts and Dudley ran.

“Who are these people?” he wondered.

Roberts, a retired economics professor at Southwestern University, in Georgetown, answers his own question in The Cedar Choppers. Based largely on interviews and newspaper archives, the book is in its fifth printing, an impressive run for an academic title; its popularity attests, perhaps, to modern Central Texans’ fascination with a group of people they replaced: a marginalized yet proudly independent band of Southern whites whose lineage stretches back to a Scotch-Irish warrior culture in the British Isles.

The mountain clans that would come to be known as the cedar choppers, or cedar whackers, first settled in Appalachia in the eighteenth century, moving west through the Ozarks before finding their way to Central Texas shortly after the Civil War. An earlier wave of German and Anglo settlers had already established farms throughout the Hill Country, but their intensive tilling and overgrazing practices quickly depleted the region’s thin topsoil, allowing Ashe juniper—a shrubby tree known colloquially as mountain cedar—to spread out of the region’s steep canyons and across disturbed rocky slopes where native grass once grew. By the turn of the twentieth century, most of the wealthy farmers had moved on to greener pastures.

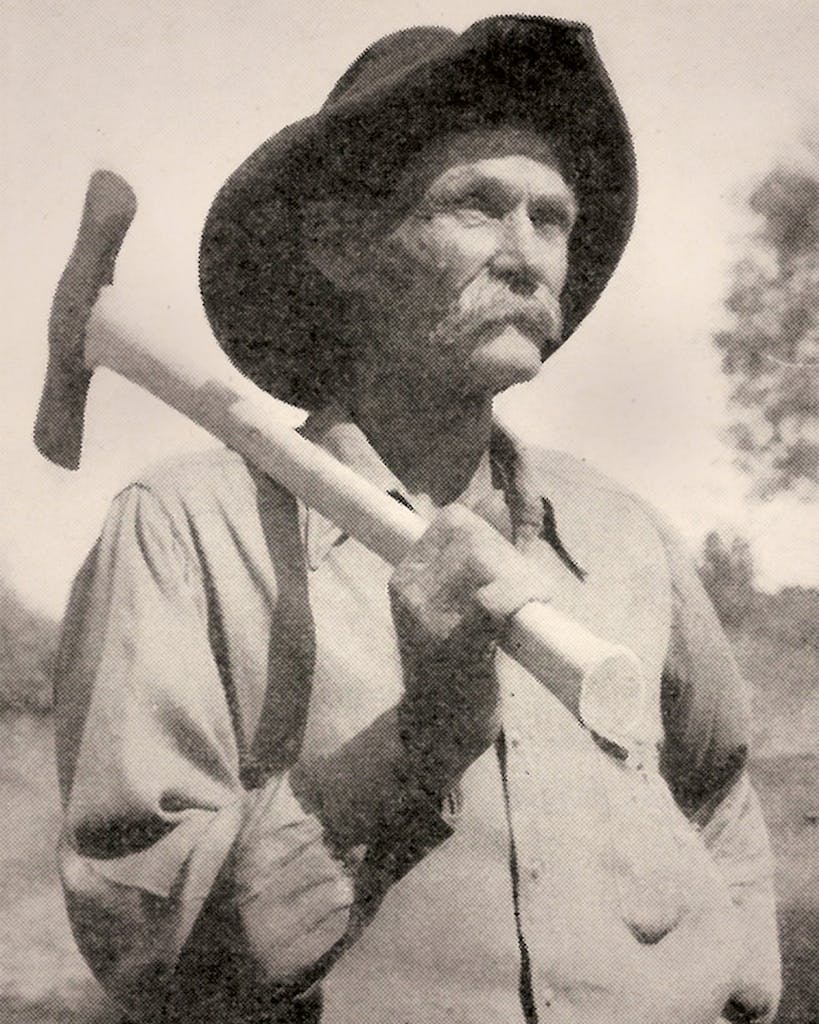

The mountain folk didn’t have much to begin with, and they were well suited for the woodlands, so they hunkered down. For generations, they eked out a meager existence hunting, fishing, stocking semi-feral pigs and cattle, distilling moonshine, and cutting cedar, which they used to build zigzagging “worm fences” and rustic barns or burned to sell as charcoal. As the nature writer John Graves explains in his 1973 essay collection Hard Scrabble: Observations on a Patch of Land, “The cedar people asked less of the land and of life than those who had come before; the land had much less to give.”

The mountain folk represented but a sliver of the Scotch-Irish people who settled in Texas, of course. “Isolation allowed them to keep their ways,” Roberts says. As the already clannish cedar choppers further withdrew from society, they became ever more insular. Folklorist Alan Lomax encountered cedar chopper families in the thirties and recorded them singing traditional English ballads like “The Romish Lady” and “Seven Long Years.” They had their own manner of speaking, distinct from their fellow Texans, and lived by a code of freedom and personal honor. “There was a lot of murder and mayhem going on,” Roberts says, “but they wouldn’t steal.”

That culture—defined by a warrior ethic, stubborn pride, a distrust of legal institutions, and a lilting dialect—is an ancient one that developed on lands bordering the Irish Sea, according to the 1989 book Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, which traces the influence of successive waves of immigration from the British Isles on regional cultures in the United States. Distinctive words like “bumfuzzled” and “scoot” and the use of an emphatic double negative—“I never sold none,” for example—as well as the figurative use of earthy terms for bodily functions, all arose in the borderlands of Northern Ireland, the Lowlands of Scotland, and northern Britain. “A backcountry granny would kindly say to a little child, ‘Ain’t you a cute little shit,’ ” Albion’s Seed author David Hackett Fischer writes.

More than a quarter million Scotch-Irish people immigrated to America through much of the 1700s. Many were desperately poor, Fischer notes. In the mid-twentieth century, however, the cedar choppers’ fortunes took a fateful turn. Ranches had begun to replace farms in agrarian Texas, and cattle required fences to keep them from roaming free. Cedar was in high demand for fence posts, and the hill people, newly incentivized, began cutting cedar at a prodigious rate and hauling it on flatbed trucks across Texas, the Great Plains, and the West, where it commanded top dollar. By the forties, Roberts writes, the once-impoverished people were flush with cash, and the name “cedar choppers” came into use. “They were making more money than any working man in Austin. That’s just astounding to me,” Roberts says. “They could make $25 a day when it might take a typical working man a week to make that much money. And they had no boss.”

Most cedar choppers didn’t use their riches to improve their long-term fortunes, however. Roberts says many of them preferred to live for the moment, eating “high on the hog” and drinking heavily. “They didn’t care about possessions,” he says, “and they lived in housing fit for animals.”

If You Can’t Chop ’Em, Burn ’Em

In the early twentieth century, cedar choppers were more widely known as charcoal makers; they burned so much cedar on the banks of the Guadalupe River that an entire section of river from Sisterdale to New Braunfels was nicknamed Charcoal City.

Old-timers in the Hill Country still tell stories about the cedar choppers, many involving violence and booze (though Roberts makes clear in his book that the rowdiest men were a minority; most of the choppers were content to lead quiet lives). One descendant of the cedar choppers interviewed by Roberts recalled wild Saturday nights in Junction, where he saw three fights happening at once, with his father in the middle of the melee. “Yeah, my daddy—hell, he’d get on a mule and ride ten miles to get in a fistfight,” the man said. (Cedar choppers also play a starring role in one of Texas Monthly’s most outrageous stories, a 1975 Gary Cartwright narrative about dogfights, which opens with a cedar chopper stabbing a convenience store clerk after an argument over a 5-cent increase in the price of a six-pack of beer.)

Though people throughout Central Texas were scared of the cedar choppers, nowhere did their nineteenth-century ways collide more forcefully with proper society than in Austin, where life revolved around the state capitol and the University of Texas. When they arrived in the forties and fifties with cedar posts in tow and thirsty for rowdy nights in bars on Sixth Street, they shocked middle-class residents, according to Roberts. The men were filthy from tree sap, which stuck to their skin and mingled with sweat and dust from cedar bark. “They lived like hell and played like hell,” Roberts recalls. “They weren’t ashamed of it.” And if you looked down on them, he adds, they’d kick your butt.

Austin’s elites, despite their fears—or perhaps because of them—responded to the presence of cedar choppers with ridicule. One country club hosted a “Hill Country Cedar Chopper”–themed dance, replete with hillbilly costumes and fake beards. Cedar choppers also entered the region’s folklore as bogeymen, featured in the kinds of scary stories told around a crackling campfire. The term “cedar chopper” became a catchall pejorative for the region’s hillbillies, not unlike “Okie” in California and “cracker” in Georgia. Today, the equivalent term would be “white trash” or “redneck.”

Of course, the cedar choppers’ heyday couldn’t last. By the middle of the twentieth century, after chain saws replaced double-bladed axes, nearly anyone was able to fell cedar with relative ease. Even more ruinous was the arrival around the same time of steel T-posts, the metal fence posts imported from Japan that quickly replaced cedar posts. Technology put nearly all the cedar choppers out of business, says Roberts, who spent his academic career researching the effects of economic change on marginalized rural people in Mexico and China, before turning his attention to the marginalized folks closer to home. “By 1960,” Roberts writes, “most of the choppers had left the hills, moving reluctantly into town and working as truckers or masons or at any job where they could maintain some semblance of independence.”

Today, only a few professional cedar choppers live alongside the vacationers, retirees, and ranchette owners who predominate in the hills west of the Balcones Escarpment. “This country’s growing over way too quick out here,” cedar chopper Nolan Allen lamented on a recent morning outside his home near the foot of the Devil’s Backbone ridge, south of Wimberley, where the exurban sprawl envelops a patch of land his family has owned for more than a century.

Nolan is no bogeyman. An affable 28-year-old with a burly physique and a handshake as rough as tree bark, he bought his first chain saw, an Echo CS-3000, when he was eleven years old to cut posts alongside his father, Stanley. “It’s something we love to do,” Nolan said. “Get out in the brush, and you can’t hear your phone ring and you’re by yourself. It’s more or less therapy, I guess you’d say. Nice and quiet, except for the chain saw, but you tune that out after a minute.”

There’s still some demand for cedar posts, and the Allens work hard to meet it. “I can cut one of them in four or five minutes,” Nolan said. He also cuts smaller sections called “stays,” which are used as fence pickets. A stay is five feet long, which Nolan measures by standing it upright and cutting it off where it reaches his shirt pocket. (His dad cuts each stay at a height between his first and second shirt button.)

One time, a man confronted the Allen brothers with a baseball bat. “Clayton fired up that brand-new chain saw and said, ‘You done brought a bat to a chain saw fight, mister,’ ” Nolan said, guffawing.

Along with Nolan’s younger brother, Clayton, the Allens work out deals with neighboring landowners who allow them to harvest the trees free of charge. “Generally what we do is we’ll cut the cedar, and then we’ll clean the brush and trim the trees and make everything look pretty,” Nolan said. If they had to pay to harvest posts and stays, he says, they wouldn’t be able to turn a profit—cedar posts fell even further out of favor about a decade ago, when prices for steel posts plummeted. These days, he said, the only people who prefer cedar fences are set in their ways, live in coastal areas where steel erodes quickly, or simply like the Hill Country aesthetic.

Nolan’s dad, Stanley, a friendly fellow in a threadbare work shirt and paint-spattered jeans, tells meandering stories in a singsongy twang that could pass for Appalachian mountain talk. He was a teenager in the early seventies, he said, when he bought a chain saw at a garage sale for his own father, who was about sixty years old and had always used a double-bit ax. “I was tired of watching him chopping all damn day,” Stanley recalled. “I drove in there, and Daddy’s out there sharpening that old ax. I got out the saw, and he said, ‘What the hell is that?’ ”

“It’s your present,” Stanley told him.

“I don’t want that damn thing,” came the reply.

“Well, you got it anyway,” Stanley said. The old man was stubborn. It took him a long time to come around to the chain saw. “He was a tough old fart, is all I can say,” Stanley recalled.

Like their warrior clan forebears, the Allens tell plenty of stories about not backing down from confrontations that erupt when they’re chopping cedar, particularly when property lines are in dispute. One woman sicced her dog on the brothers (the dog apparently didn’t know what “Sic ’em” meant; it ran around but didn’t attack). Another time, a man confronted them with a baseball bat. “Clayton fired up that brand-new chain saw and said, ‘You done brought a bat to a chain saw fight, mister,’ ” Nolan said, guffawing.

Nolan shrugged off the dangers inherent in working with gas-powered, razor-sharp saws. “We’ve had a few close calls, but nothing bad,” he said, proceeding to describe a friend who nearly cut his own hand off. Another time, about a decade ago, Nolan tripped on a piece of barbed wire. “When I tried to throw the saw out from under me, it caught my knee and chewed it up,” he said. “I could actually see my kneecap in there. I rubbed Purell in it, tied a Band-Aid around it, and kept going.” A friend told him he should seek immediate medical treatment, but Nolan didn’t think it could be stitched up, and he didn’t want to miss work. “It was pretty gnarly-looking,” he said of the scar, “but it’s about gone now.”

Nolan has heard the scary stories about cedar choppers that have been circulating in the Hill Country for generations. He thinks the legends grew because he and his brethren have such imposing physiques. “You spend all day carrying a chain saw or carrying post, and everybody’s built,” he said. “Like me, I’m kind of round, but I can pick up four hundred pounds and walk off with it, all from cutting cedar and firewood.”

The Allens admit they’re among a dying breed. “We’re narrowed down here, but we make the best of it,” Stanley said. For Ken Roberts, though, the cedar choppers’ presence is as vivid now as it was when he first encountered them, more than six decades ago. “It’s like they were from another country, another language, another culture,” he says. “And only people who live along the Balcones Fault know who the hell they were. Nobody else does.”

This article appeared in the August 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Edge Dwellers.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Hill Country

- Austin