This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I must have been four years old the day the jeep blew up. There were four of us: me, my six-year-old brother, Eli, my father, and my grandfather, who owned both the jeep and the ranch where we were burning the dead cedar that the two men had just finished chopping down. It was a hot summer afternoon, and I suppose the men had gotten tired of hefting logs, because they had begun to use the jeep to ram the wood into the bonfire. I remember with a stab of clarity the moment the jeep got stuck: the roaring of the accelerator, the cursing, the sudden sickening smell of burning rubber, the flames jumping . . .

The next thing I knew, Eli and I were in midair—he in my grandfather’s hands, I in my father’s—and moving uphill at incalculable speed. I didn’t look back, not until we reached the barn at the top of the hill and my brother and I were deposited on bales of hay. The jeep below us was not a jeep anymore. It was a giant, raging fireball, and as some ammunition in the glove compartment exploded, I started to cry. I remember bawling for some time. Then it began to rain. Through tears I watched the raindrops bombard the fireball. My father squeezed me, and I heard my grandfather say, “Don’t worry, little pal. We’ll get another jeep.”

Perhaps an hour later, the thundershower had subsided, the summer sky was a cloudless blue, and the jeep was reduced to a black hunk of smoldering metal. The four of us walked back to the ranch house. My mother and grandmother fixed us lunch. Then the two men got into my father’s car and drove off. They returned that afternoon in two vehicles. My grandfather had bought a new jeep in San Marcos—had cut a check for it and driven it off the lot, back to his 365-acre ranch in Wimberley.

We all have our signature moments, and this childhood memory is mine. For this was the notion that held fast—that in a child’s paradise there will be fire; yet for every fire, there will be strong hands to spirit the child from danger, and rain to douse the flames, and thus a paradise restored. It is the fanciful stuff of youth, a world of calamity and heroism and heaven on earth; but I had proof that it was true. And long after I quit counting on the hands and the rain, I still had the ranch. I still had paradise.

Today the ranch is listed as a bed and breakfast. We sold Circle J Ranch last June 1 to a wealthy young Dallas couple—an inevitability, considering that no one in our family could afford its upkeep following my grandfather’s death 12 years ago.

The new owners had hinted that they might convert the guesthouse to an inn. While packing up our family’s 35 years’ worth of accumulated junk over Memorial Day weekend, I heard my father say, “You know, I wouldn’t mind at all coming back here in a few years and staying at their inn, just to see what they’ve done with the place.”

I looked up at him in amazement. My father managed a brave smile, and while blinking back tears—his eyes had been red all weekend—he said, “We weren’t the first ones to own this land, after all. We had our time, and God knows I’m thankful for it. Now it’s someone else’s time.”

In addition to having strong hands, my father has a viselike grasp of reality. The puniness of my own grip notwithstanding, I have no sense of entitlement when it comes to property. One should be thankful to have a roof over one’s head; to own a home, that much more so; and to be the beneficiary of a family spread, one must regard oneself as especially blessed. Still, loss is loss, and there is an intense bond Texans have with their land, which, when severed, spills out an undeniably rich blood. As the old landowners pass away, as wealth changes hands, as the country gives ground to the city, and as longtime Texans give ground to newcomers, the spilling of this blood is impossible to ignore. All across the state—though particularly in the Hill Country, where Circle J was located—increasing numbers of once-sizable refuges from civilization are being diced up into one-acre tracts or manicured into corporate resorts and weekend retreats. I had never felt a kinship with landowners, but now I share deep feelings with those who have had to leave their property. Of course, it may be that some of us looked to the land for a peace that might have been better cultivated within ourselves. Lately I’ve been trying to convince myself that paradise lost may lead to serenity gained. But what has leaked out of my life will not be easily replaced.

We called it a ranch because that’s what it looked like, though in truth little in the way of ranching took place there. My grandfather bought Circle J for about $30 an acre back in the early fifties, when the closest town, Wimberley, consisted of not much more than a country convenience store and a gas station where minnows could also be bought. The 365 acres encompassed a gorgeous ripple of cedar hills, with a single beaten road that began at a crossing of Lone Man Creek and ended two miles later at the foot of a stone ranch house. Spring-fed creekbeds curled through the hills like limestone veins. From the peak of the property off to the west, you could stand among the cactus and the bluestem grass and view a seeming eternity of untrampled green. A short walk from there led to a deep and heavily thicketed valley where deer communed and turkeys roosted. A long meadow appeared just beyond and then tumbled down to the creek, which ran alongside a forest that rose to other hills, meadows, and secret valleys.

No day’s hike was without discoveries: antlers tangled in barbed wire, a long-overlooked grotto swaddled in fern, a baby blue heron overhead, a massive oak split neatly in two by last night’s lightning. The ranch was always the same, always changing. One summer, when I was thirteen, my grandfather paid me to paint every metal fence post on the property. The task should have taken me a few days, but I stretched it into weeks, and I think the exhilaration of being out in the wild for long periods made me a little crazy. I returned from the job with my work boots painted a bright silver. That fall I wore my silver boots to school, and even my closest friends took pains to avoid me.

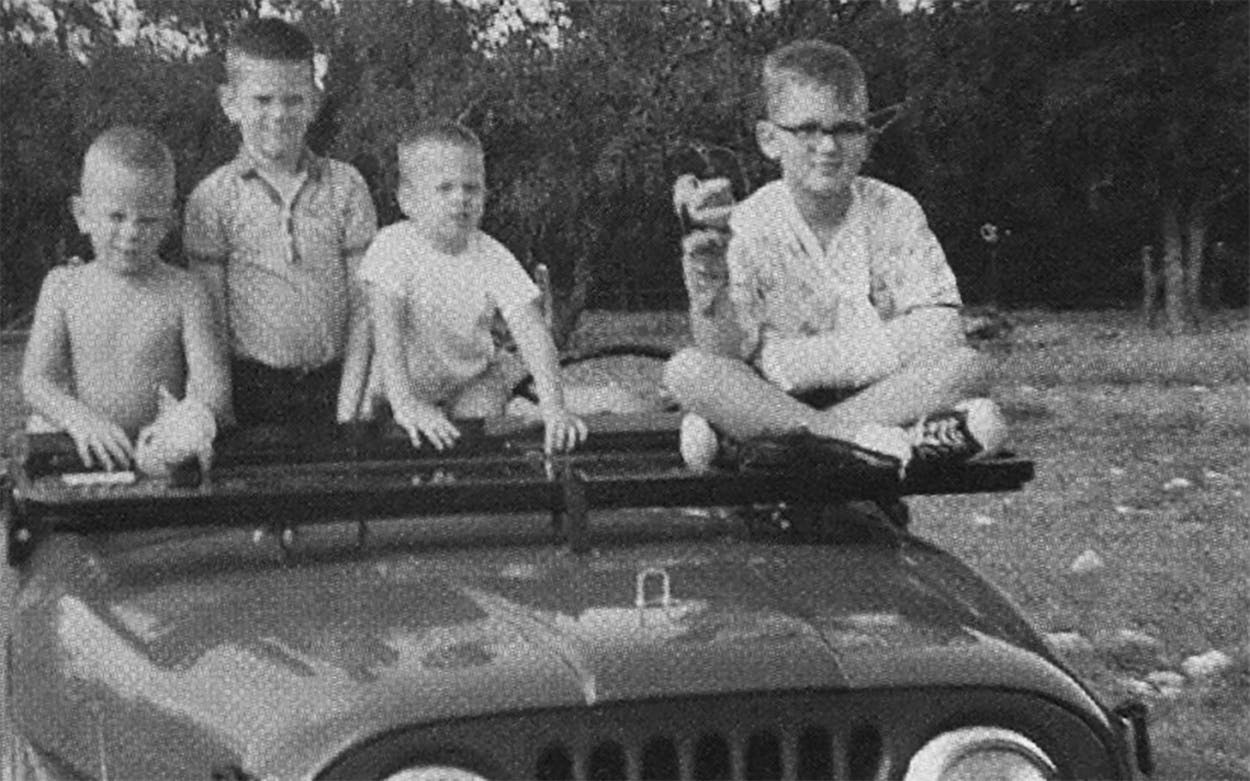

Though our family lived in Houston, the better part of our summers, holidays, and weekends were spent at Circle J. Almost every one of my childhood memories is rooted there (including my earliest, which involves me as a three-year-old half-wit sticking my finger into the water pump and being ferried off, bleeding and whimpering, to the San Marcos hospital to get stitched up). Mornings I would awaken to the smell of my grandmother’s buckwheat pancakes. By the middle of breakfast, my father and grandfather would emerge from outdoors, caked with sweat and wood shavings from ridding the ranch of its deadwood. My mother and aunt would then return from town with the morning’s paper, which my grandfather would take with him to the pool. The five boys—my brothers, Eli and John, my cousins, Mike and Joey, and I—filled our days with baseball, splash tag, kick the can, or fantasy games in which the two eldest (Mike and Eli) would inevitably torment the two youngest (John and Joey), and from which I, being the chronological middleman, would find myself excluded, suddenly alone but for the ranch. For hours I would comb the Indian mounds for arrowheads or walk the creek, bamboo pole in hand, and seek out the five-pound bass that had snapped my last pole in half and left me quivering in shock by the water’s edge. By dusk I would return to find my father standing over the barbecue pit, immersed in smoke, while my mother and aunt played “Ode to Billy Joe” endlessly on the record player. If my fishing luck had been lousy (it usually was) and I appeared morose at the dinner table, my grandfather would say to me, “Little pal, how about we get up at five tomorrow morning and catch a few?”

Though nothing terribly serious was meant to take place at the ranch, the family had gotten into the quarter horse business, and more than a hundred of the beautiful beasts roamed the acreage. Riding them was an unsurpassable joy, but even to feed them or pet them or simply watch them stamp their restless feet in the morning frost made me feel like a witness to something vaguely spiritual. The task of training the horses belonged to a noble-faced man named Vicente, who was secreted across the border with his pregnant wife at my grandfather’s direction and moved into a trailer near the barn. (All four of their children would be born and raised on the ranch.) I learned to love animals by watching Vicente’s silent communion with the horses. He was a gracious and tolerant man who indulged us five brats when we tagged along behind him. We were distraught the day he quit after the caretaker had been bullying him. My grandfather responded by firing the caretaker, and Vicente returned.

For a boy, the days at the ranch were distinctly episodic. There was the morning a deadly coral snake slithered out of a woodpile and coiled itself around the gloved hand of my grandfather, who coolly bashed its head in and presented the carcass to his awed grandsons, who were still poking at it long after it had gone stiff. There was the summer drought in the mid-sixties that culminated in a sudden grass fire, which we fought using hoses and wet towels with the desperate fury of knights staving off dragons. There was the two-day search for our family dog, a wanderlustful basset hound named Rosie, whom my grandfather finally found at the edge of the property, rolling in a ditch filled with horse manure. There were scorpions in the bathtub, deer nosing around in the toolshed, fireworks on the Fourth of July, thunderstorm-induced power outages that left us huddled over candlelight. There was the full-moon evening when we boys watched with befuddled delight as the adults, led by my frisky aunt Fran and emboldened by booze along with some physical imperative, descended one by one into the swimming pool, fully clothed, and splashed about in a display of what could only be called Presbyterian group foreplay. Within the ranch’s barbed-wire borders, we could all be children.

But childhood would not protect us. One summer night in 1972, my cousin Mike—then eighteen and home from his freshman year at Duke—drove from the ranch to a party in Marble Falls and, on the drive back, flipped over his car and was killed. I remember roaming the ranch that summer in Mike’s clothes, crying and worrying about the fate of my childish illusions—with good reason, it turned out. Within the next few years, the family was beset by divorce, alcoholism, and a rebelliousness that consumed the four remaining grandsons. By 1979 my brothers and I were all at the University of Texas at Austin and using the ranch for wild parties, which did not amuse my grandfather. That Thanksgiving, it was a decimated and rather tense group that congregated around the dining room table. Mike was dead, Joey was in London with his divorced parents, and my brothers and I were smoking, drinking, dragging our mangy young beards through the gravy, and arguing with the adults about whatever our government professors had taught us. After the meal, Eli and John and I retired to a spot on the ranch that overlooked a valley, the creek, and vistas far beyond. We smoked cigarettes and speculated aloud about which of us would be the first to marry. It was the last time the three of us would sit together. Two weeks later, Eli was killed in a motorcycle accident. After the funeral in Houston, my grandfather sat nervously with us for a while. Then he got into his car and hightailed it to the ranch, where no one would see him cry.

Three years later, in 1982, my grandfather died on the ranch while chopping wood. From that moment on, we knew our days at Circle J were numbered. I chose not to think about it. The ranch and I had become closer than ever. After his death, I took it upon myself to stock the creek with fingerlings, just as my father still rose early to rid the acreage of its deadwood. In 1984 I decided to be a freelance writer. To keep costs down, I moved out to the ranch and lived in my grandfather’s study for the next two years. It was a time of poverty and deep frustration. For spiritual solace, I leaned heavily on Circle J. I still fished the creek, still sought refuge in the Indian mounds. Outside the ranch’s boundaries, things were changing, and not for the better: The hills were scarred with tract houses stacked against each other, and drowsy old Wimberley had become a ghastly aggregation of ye olde shoppes. But the ranch still offered the dark majesty of owls in their evening predation, the blur of foxes in the meadow, the wild crash of thunderstorms, and utterly silent starlit nights.

One weekend morning I arose from bed to find the ranch a foot deep in snow. No one in our family had ever been blessed with such a sight, and thankfully my girlfriend was there to plunge into that exquisite spectacle with me. When she moved to Japan in 1986, I said goodbye to the ranch and followed her. In 1988 we married and bought a house in Austin. Four years later, our marriage was coming apart. I moved out of the house. Though I was utterly clueless as to what would become of me, there was no question about where I would be going. Again the ranch awaited me. Again I fell like deadweight into its embrace, and fished for my dinner, and swam in the pool at midnight.

But the ranch needed more than I could give it. Paradise was eroding: Its road had deteriorated, its well was drying up, and the dams in the creek were leaking. Trespassers were shooting the deer and plundering the Indian mounds. My grandfather would not have tolerated such defilement, but we were helpless to prevent the intrusions. Lacking any choice, we put the ranch on the market. The years passed without any serious offers, and I prayed for some financial miracle that would keep Circle J in the family, while another part of me prepared to say good-bye.

When news of the impending sale of the ranch reached me last year, it was springtime, ordinarily the finest time of year to fish, but I could not bear to go near the place. Let this death be as swift as the others, I thought. I busied myself at work and did all I could to forget. At last, Memorial Day weekend came, and our family convened at Circle J a final time to straighten things up. When I arrived, my parents and other relatives were already inside the ranch house, dividing up the belongings that would not remain with the new owners: rifles, fishing tackle, yellowed photographs, old hunting clothes, tacky knickknacks like the one in the toolshed that read, “Ma loved Pa. Pa loved wimmin. Ma caught Pa with two in swimmin. Here lies Pa.” It was an event to endure. That night I grabbed a few blankets and made for the creek. When I closed my eyes, I could see my grandfather and his little pal standing together on the dam, holding their bamboo poles high. Sleep did not come easily, but I awakened to a brilliant sky and bathed in the creek before returning to the others.

I stayed one more night after the rest of the family left. How to say good-bye, I wondered. I fished all day, fully intending to rid the creek of every bass I had stocked it with. By late afternoon I had caught more than two dozen, but shame overtook me—I heard my father’s voice: “Now it’s someone else’s time”—and I threw them back for the next fisherman to catch. Then I remembered a bag I had found earlier in the toolshed. Inside it were perhaps a hundred firecrackers, the remains of some ancient Fourth of July. I drove to the spot on the ranch where, more than thirty years ago, I had watched the jeep explode into flames. When I ignited the entire bag, threw it to the ground, and ran, it was my own legs ferrying me uphill this time, and all the tears were long gone. But the explosions left me as breathless as before. When the last report sounded and was replaced by a heavy silence, I suddenly felt unbearably old.

The ranch house was dark and empty. I jotted down a note to the new owners, welcoming them and assuring them that they had purchased God’s country. Then I returned to the spot above the valley where Eli, John, and I had sat together. I stood there, regarding the vista, which, despite all the development in the hills over the past decade, still shimmered like an ocean of cedar. Something needed to be said. I opened my mouth and proceeded to shout out the names of every one of us, one by one, those dead and those yet alive and in my company—all of those whose voices were here for a while, when it was our time. Each name rocketed through the spring air, echoed, and then was gone.

On the way out, I took down the wooden Circle J Ranch sign at the entrance. It would not fit in my car. What did I need a sign for anyway? I turned it on its face in the bluestem grass, hopped into my car, and drove back to the city, still smelling faintly of fish and cedar.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Wimberley