This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

An exemplary story from the annals of modern-day Houston:

A lawyer with one of the Big Three firms—let’s call him Joe Don, so as not to blow his cover—gets a call one afternoon from a panicky client who asks Joe Don to present himself immediately at the client’s conference room downtown; it seems that two lawyers from New York are in town trying to add a last-minute protective clause to an important deal, and if the clause goes in, the deal will die.

Joe Don hustles over and sizes up the competition. The lawyers from New York look exactly the way he’d expected them to, all done up in pinstripes and wing tips and gold collar pins. He decides to name them, privately, Lodge and Cabot, although he’s careful to remember their real names, too, and use them in every other sentence. Joe Don is wearing a conservative suit himself, of course, but he’s different from Lodge and Cabot in ways that are immediately clear to him and to them. His suit is a little more rumpled than theirs. He has a little more meat on his bones. He remarks on how we could use some rain and doesn’t Oklahoma look tough this year, which comments elicit too-polite chuckles from Lodge and Cabot.

This is just what Joe Don was expecting and hoping for, and it opens the way for him really to go to work. First he asks a couple of questions about that ol’ clause that show he hasn’t the faintest understanding of it, and then he goes into his sales pitch. “Well, now,” he says, “y’see, Lodge, and you too, Cabot, it’s just like I was sayin’ to my wife this morning: if a man’s got a broken fence, then he better be a real good neighbor. And that’s what I try to be, and that’s why this ol’ clause is about as useless as tits on a big ol’ bull boar. Like my daddy used to say, if you can build it straight or build it crooked, why, you better build it straight. You see what I mean?” (They don’t, and Joe Don knows that perfectly well.) “So, boys, let’s just go to the house on this one, what do you say?”

In the course of this soliloquy, broad and indulgent smiles have begun to crease the faces of Lodge and Cabot. Joe Don can tell exactly what they’re thinking: this poor guy is so completely out of his depth, so dumb, so innocent, so—in a word—country, that it’s impossible that we’ll ever really need that clause. Joe Don is especially proud of his line about his wife, which he has only recently perfected; guys like Lodge and Cabot never begin important business meetings by announcing what they told their wives that morning. “Okay, Joe Don,” one of them—either Lodge or Cabot—says, trying hard not to be patronizing, and failing, “you win.”

Poor Lodge, and poor Cabot. They got country-boyed.

Quotes for Country Boys

On one’s father: “Daddy never had much, but he knew a lot more than most folks.”

On one’s mother: “I wasn’t ever much to look at, but I had a mama who believed in me.”

The country boy has emerged in the last decade as perhaps the dominant social type in urban Texas. He is, literally speaking, neither country (he lives in a city) nor a boy (he is a full-grown man—or woman; the country boy is a genre, not a gender). However, he can at least lay claim to rural or small-town roots, and he finds it both comfortable and convenient to make these roots the constant reference point of his white-collar life. In surgery, the country boy feels the need to invoke a metaphor about hogs; when receiving visitors in his real estate office, he plays country-and-western music; his accent, nearly extinct in the privacy of his home, thickens perceptibly when he’s selling insurance. The country boy is Lyndon Johnson, careening down caliche roads on his ranch in a Lincoln convertible for the benefit of the Washington press corps; he is Darrell Royal, barely able to utter a sentence about football that doesn’t also include an agrarian homily; he is H. L. Hunt, hustling quarter-section farmers out of oil royalties and doing the figuring on the back of an envelope.

He is not a redneck, that being an involuntary condition, although he may have been one once and gotten over it. He is probably a good ol’ boy, but that doesn’t define him precisely enough; it is a category that includes anybody in any walk of life who has a vaguely hail-fellow-well-met Southern manner. The country boy clearly wants to be—has chosen to be—a country boy, just as surely as he has chosen to leave the country behind. He is not without artifice, as he will cheerfully admit. He lives his life a certain way in order to make a point, both to the rest of the world and to himself, about the sort of bargain he has struck with urban life. He has, at bottom, three defining traits: He is not a native of the city where he lives. He presents himself as fundamentally simple, in touch with the basics of life and uncomfortable with the obvious signs of sophistication (although he’s not at all uncomfortable with money, as long as it’s used in an unsophisticated way). And he doesn’t take himself too seriously; he aw-shuckses.

Rules to Live By

1. Always communicate that you’re in touch with the external verities—for example, eating, sleeping, family, death.

2. Always know how the ball club is doing and what the weather is.

3. Don’t have an analyst unless he’s a stock analyst.

4. Don’t have “relationships” unless they’re relationships with your clients.

5. Hunt, fish, play golf, or do all three, but don’t jog.

6. Rise early and eat a big breakfast.

All of which works to his spectacular advantage. Ben Barnes, one of the all-time great country boys, became Speaker of the Texas House at the tender age of 26 by lining up all the pledges he needed (“He told me, ‘You and me cain’t let the city boys take over the state,’ ” says one pledge) before any of the real Speaker candidates even knew the job was going to open up. Will Caruth, of the Dallas landowning family, country-boyed Raymond Nasher, the developer, so well when they were making their deal for the land on which NorthPark Center now stands that today the Caruths’ foundation, not Nasher, still owns the land. Congressman Charles Wilson of Lufkin, who never owned a pair of cowboy boots until he went to Washington and has a sign on his office wall that reads, “Just a Country Dog Come to the City,” got independent oilmen a spectacular tax break back in 1975 by artful country-boying. “We kinda aw-shucksed our way into it,” he says. “We kept talking about the little independents. Now, that includes Corbin Robertson and George Mitchell, but the Yankees don’t know that.” Dr. James “Red” Duke of the UT Medical School at Houston has built up a huge, high-profile trauma center at the Hermann Hospital emergency room, but he explains his success with “I’ve often said if a fella has enough common sense to raise chickens, he probably can be a good surgeon.”

Shopping

Never go to a boutique; a department store, even a fancy one, is much more country, because it’s in the spirit of the old one-stop dry goods store back home.

In the Northeast, if there is any prevailing pretension that city people have about their backgrounds, it is that they grew up in the most urban setting imaginable: witness New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s endless references to his tough boyhood in Hell’s Kitchen. Why is the opposite true in Texas?

Leisure

Don’t waste time trying to discover charming, out-of-the-way vacation spots; country boys, being unsophisticated, have a great time at the obvious places. It’s good to own a boat, too, as long as it has a big motor.

The answer is that Texas is in a particular historical moment: the moment when the generation raised while the state’s population was shifting from rural to urban has come to power. At that moment, inevitably, the notion that urban success rests on rural roots will always come to the fore, because it reflects the experiences of the group of people who run things. It is happening in Texas now; it happened in the Northeast and the Midwest once, too. Horatio Alger, the watery-eyed small-town novelist who was the great mythologist of American success, spent thirty years telling and retelling the story of the rural lad who makes good in the city. Theodore Roosevelt, born and raised in Manhattan, asserted in 1910 that “from the beginning of time it has been the man raised in the country—and usually the man born in the country—who has been most apt to render the services which every nation most needs.” So concerned was Roosevelt with the evaporation of the nation’s incubator of leadership that, as president, he appointed a Commission on Country Life to look into the problem.

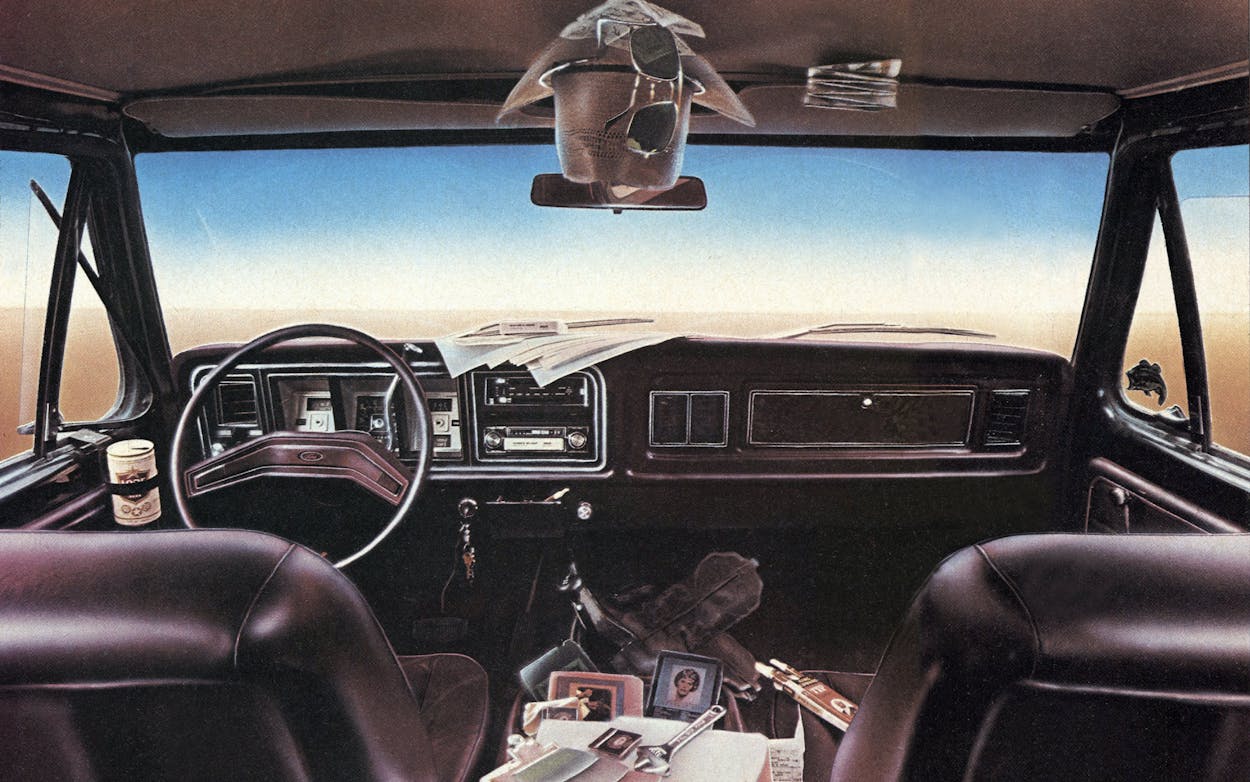

Transportation

Always drive an American car, a big one if possible. An Olds 98 is fine for the city, but of course you ought to have a Chevy Blazer for hunting, fishing, and ranching.

The year Roosevelt appointed the commission was 1910, which was also the last year that the United States’ population as a whole was mostly rural. In the intervening years, the country boy ethic has gone cold dead in the North. But Texas, by the Census Bureau’s calculations, was 55 per cent rural as recently as 1940, though by 1970 it was nearly 80 per cent urban. So while in most of the country the entire working population was born into a basically urban society, every native Texan over forty was born into a basically rural one. No wonder the presumed link between rural upbringing and urban success still exists here. It fits most people’s life stories.

Quotes for Country Boys

On foreign affairs: “Right now it’s third and long against the Russians, and if we mess up we’re gonna have to punt.”

The historical moment aside, Texas is a state long dominated by agriculture and the Democratic party, and thus it is part of a rich American tradition of hostility toward cities that runs from Thomas Jefferson (who wrote in 1797 that farmers “are alone to be relied on for expressing the proper American sentiments”) through the Populists (who did extremely well here), yea, even through the governorship of Dolph Briscoe. And besides that, Texas stands out among agricultural states for the tenacity with which it clings to the idea that status is a function of landholdings. Why shouldn’t it? Not only did the old ethic of “buy land and never sell” pay off in the days of the cattle kingdom but when oil transformed the state, it continued to pay off, in the form of royalties. An industrial, city-based status system with no relation to the land never got much of a hold here. Even today, Texans are uncomfortable with urban forms of status (bureaucratic titles, professional credentials) and tend to parlay them as quickly as possible into the ownership of rural land, just to be sure. It’s still better in Texas—for your image, if not your bank account—to have 640 acres of scrub than to be a vice president for sales and marketing.

The Myth Begins

The frontispiece of this Horatio Alger novel, circa 1872, shows what kind of roots a boy needs to make it in the city.

So it’s natural that city Texans still want to be country. That’s where the mythic goodies are. And as for the particular style with which they act out their rural yearnings, it is the product of a couple of Texas traditions of its own. The first is Southwestern humor, the coarse, self-mocking braggadocio that grew up in the early 1800s on the frontiers of Tennessee and Kentucky and was carried west to Texas by men like those who fought at the Alamo. The point of Southwestern humor was to take the edge off a rough way of life and to turn frontier people’s awful worry that they were irredeemably crude into a joke. As Kenneth S. Lynn, author of the best book about Southwestern humor, wrote about Davy Crockett’s public speaking, “When he joked, as he often did, about how stupid he was, he damped down both his own insecurity and [his listeners’] as well.” Southwestern humor caught on especially in Texas, perhaps because this was a frontier state for so long; isn’t it possible to make out the line that connects Crockett’s jokes to the “roasts” that prominent Texans love so well today?

Quotes for Country Boys

On one’s wife: “We’ve sure had a lot of ups and downs, but she’s a good woman.”

On one’s kids: “Joey’s a little spoiled, but he’s a hell of a competitor.”

On economies: “Give a man a chance to work, and he’ll do just fine.”

The second particularly Texan tradition that helped create the country boy style is the state’s long history, only now ending, as a colony of the urban North. Texas cattle were driven to Kansas and Missouri to be put on trains for Chicago; Texas cotton went to New England; Texas oil, a cheap raw material until ten years ago, was sold to New York companies. Being that dependent on outsiders meant that it did little good to act shrewd in business dealings with the city folk, because in a straight test of strength the Texan would lose. What worked better was playing dumb and hoping they’d underestimate you. Thus the small-town lawyer always tried to win his case against the big-city boys through folksiness, not force; thus, even now, the instinctive reaction when somebody from the East Coast calls on business is to thicken your drawl a little.

Culturally, Texas’ colonial status has been even more difficult to get rid of, and it is only recently that country-boying has been perceived as an effective weapon in the war against being thought of as a hick. The oldest generation of country boys now operating in Texas—men like John Stemmons in Dallas and Leon Jaworski in Houston—communicate the sense that the thought of acting any way other than country never crossed their minds; that was just what they were, and of course they’d be looked down on by New Yorkers and the like. The middle generation—those now in their fifties and sixties, the John Connallys and Ben Loves and Lloyd Bentsens—saw a way to avoid being considered hicks, which was to make a point of not acting country. So they took pains to seem urbane and worldly.

The generation under 45—the one now coming to dominate Texas—has seen, by contrast, that it has two options: acting sophisticated or dropping out of the cultural competition with the East Coast entirely and acting just a bit more country than the facts would warrant. By country-boying, instead of aspiring to the dubious distinction of being considered worldly for a Texan, you could set up an entirely separate status system in which you would succeed and the sophisticated city boy would fail. We are now probably in the all-time golden age of country-boying. To country-boy successfully, you have to be at least slightly country, which the current crop’s children—big-city born and bred—won’t be. When they come of age, the art will, most likely, die a gradual and unwilling death.

Dining

If you’re going to spend a lot of money, that’s fine, but don’t spend it in a restaurant that serves small portions.

So the classic country boy today is, let’s say, forty, and lives, let’s say, in Houston, that being the one of the three giant Texas cities that values sophistication the least. He is liable to work in any field, though jobs that have an aura of labor and the land about them—the oil business, suburban homebuilding, even the more physical specialties of medicine—particularly appeal to him. He might have grown up on a farm or in a small town, and then again he might have grown up in Longview or San Angelo. He is better off than his parents (who were better off than their parents) and completely happy about it. He likes himself rather better than he has a right to. He went to college, possibly at UT-Austin but ideally at A&M, and majored in something practical, like engineering or business or petroleum geology. He listens to country-and-western music and is struck from time to time by how perfectly some song’s lyrics apply to him. He lives in a house, most likely in the suburbs and most likely new; country boys don’t renovate, as a rule. He drives an American car: a Cadillac if he’s made it big, an Oldsmobile if he hasn’t, a Chevy if he’s still trying to get his break.

Drink

Country boys don’t drink white wine and other fancy stuff; stick to Scotch on the rocks.

He goes to church on Sundays. He is married, and worries, with justice, that he isn’t good enough to his wife. He owns a farm in the country, of course—it was the first thing he did when he began to have a little money to spare—but he doesn’t get there as often as he should. From time to time he and his wife have a few drinks and talk about chucking it all and moving back there, but both of them know they’re not really serious about it.

In his office he keeps his diplomas, a bunch of signed photographs, football schedules, an eight-track tape deck, a piece of Western art or two, and the horns of a bighorn sheep he once shot in West Texas. He doesn’t keep his desk clean. He is active in the Fat Stock Show, which besides being fun raises money to help country-boys-to-be. He calls his secretary “honey” (and his wife “darlin’ ”).

He owns a four-wheel-drive Chevrolet Blazer Silverado, which he bought for the farm but uses mostly for hunting and fishing trips. He thought about getting a pickup instead, but somehow that seemed a little like overdoing it to him, in the same way that wearing boots to work is beginning to seem a little like overdoing it. On vacations he likes to go to South Padre Island or Kerrville or, in a splashier mode, to Las Vegas or Acapulco. He and his wife are planning to take the kids to Europe one day soon, but they’ll stick to London and Paris and it will be made clear to everyone what a big deal it is. More and more, he finds himself going to expensive restaurants, but only the kind that serves generous portions.

He says “bidness” instead of “business,” and “fixin’ to” instead of “going to.” He never starts any conversation with the business at hand. He has recently begun to vote Republican, but he wonders what his daddy would think. If he has an outrageously country name, like Billy Don or Benny Frank, he has shortened it to Bill (as Billy Don Moyers did) or Ben (like Benny Frank Barnes), but he’ll never be a William or a Benjamin. He knows how to tell a story and how to dig a posthole. He doesn’t put much stock in the Moral Majority, because he believes in letting other folks alone. He can walk into a bait-and-grocery store on some godforsaken ranch road and get along fine with the people inside; in fact, this ability serves him well in his business, in that it comes in handy when acquiring oil leases or tracts of development land from farmers who don’t like city people.

He is completely uncomfortable talking about his psychology and completely comfortable talking about his values. He is capable of wonder. He still looks up at the big buildings when he walks through downtown Houston. He is proud of not having made his life any more complicated than it really is. He can converse freely, after a couple of drinks, about love and death and mystery, and about lust too. He is nice to everyone, but he trusts only his friends. He never lies and hardly ever tells the complete truth, either. When he meets someone, he wants to know where they’re from, just as he wants them to know where he’s from. He likes to do business with relatives. He believes deeply in common sense. He is impossible, on personal acquaintance, not to like.

He feels vaguely guilty about raising his children in a big city, which he feels is somehow a fundamentally unnatural form of social organization. They’ll get along fine, of course, but they won’t be able to speak with even pretended authority about plowing and sunrises and fences as if all those things really mattered.

Once a year he goes back home for a big family reunion. The women cook and the men laugh and swap stories and everyone catches up on everything. Then the women put the food in big covered dishes and the whole family goes to the graveyard to clean up the plot, because it isn’t subject to perpetual care like family plots in city cemeteries are. They mow and edge the grass and put out some flowers and reminisce some, and the country boy always bows his head for a minute before his parents’ headstones. It’s odd, but at that exact moment, just when he should be thinking about his mama and daddy, one thing always occurs to him. There’s no space left for him.

A Day in the Life of a Country Boy

Country boys always get up early.

“Honey, come get your biscuits while they’re hot! Also your eggs, your sausage, your pancakes, your grits . . .”

If you want to be really competitive, you got to have a comfortable office.

“Honey, bring me that coffee while it’s hot!”

The key to buyin’ development land is establishin’ a rapport.

“I know farmin’s tough, Floyd. That’s why you got to think about your security.”

One thing about deals is, sooner or later you’re gonna end up seein’ your banker.

“I’m just a dumb ol’ boy, Mr. Witherspoon, but can we make this kind of a wraparound deal with a three-year balloon payment?”

Golf’s a real good way to do bidness.

“So then I said to him, ‘Now you’ve quit preachin’ and gone to meddlin’.’ ”

A man oughta have a little spread in the country.

“Sometimes gettin’ out to the ranch is a pain, but these kids got to get some dirt between their toes.”

The Country Boy Hall of Fame

The men who invented the style.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Geneva, Switzerland, and Paris, France. Invented the “noble savage,” the all-natural ornament of eighteenth-century civilization and great-great granddaddy of the country boy.

Abraham Lincoln, Hodgenville, Kentucky, and Washington, D.C. His political handlers exploited his rail-splitting background for all it was worth, though he was really a lawyer; nevertheless, a man in touch with the basic values.

David Crockett, Greene County, Tennessee, and (briefly) San Antonio. A tough, mean politician who aw-shucksed with the best of them and built a calculated superfrontiersman image for himself to serve his ambitions.

J. Frank Dobie, Live Oak County and Austin. Started his career teaching Shakespeare and Milton, and wasn’t getting anywhere, so he began writing about horses and cows and dramatically reversed his fortunes.

Lyndon Johnson, Johnson City and Washington, D.C. Learned the art of political country-boying from his father, then became its Leonardo, introducing horrified world leaders to the gritty realities of Hill Country ranching.

Darrell Royal, Hollis, Oklahoma, and Austin. Completed the metamorphosis of college football into a sport one step away from farming, via an unmatched mastery of the down-home metaphor.

Still Aw-Shucksing Their Way to the Top

The leading active practitioners.

Lady Bird Johnson, Karnack and Stonewall. Plays the role of widowed ranch lady and country grandma but is tough and shrewd, and knows how to play hardball when she has to. Heads a network of female country boys.

Walter Mischer, Karnes City and Houston. Master of a vast real estate and financial empire and probably Texas’ premier behind-the-scenes political operator, he acts like he just rode into town on a load of melons.

Earl Campbell, Tyler and Houston. No fur coats, jewelry, or other accoutrements of pro football stardom for him. Built his mama a new house in Tyler and, in a brilliant stroke, left the shack where he grew up standing next to it.

Ronald Reagan, Tampico, Illinois, and Washington, D.C. Simple as the day is long, or so he’d have you believe; tells jokes on himself, talks lovingly about his small-town boyhood, ranches, and never, ever, feels guilty.

Bill Moyers, Marshall and Long Island, New York. Humble and pious, equally deferential to the great and the ordinary, seemingly ambitious only to help other people. Miraculously, Billy Don has still done all right for himself.

Robert Strauss, Stamford and Dallas. Tried to solve the Middle East crisis by just bringin’ the boys to the table. Everybody knows it’s an act, but Strauss can pull it off because he knows it’s an act too.

City Boys

They don’t even try to be country, but somehow they’ve done all right.

Tom Landry, Mission and Dallas. The human computer as Texas football coach. Never said a homey thing in his life; on the other hand, works for men named Clint and Tex, and maybe that saves him.

Stanley Marcus, Dallas. The country boys’ city boy; figured out how to be the arbiter of taste—never unsophisticated, but always unmistakably Texan—to three generations of the newly urban, who seemed oddly grateful.

Lloyd Bentsen, Mission and Washington, D.C. Has the roots to justify a country boy act but apparently never had the urge. He is impossible to picture driving a pickup or talking about his mama.

Gerald Hines, Gary, Indiana, and Houston. Even country boys don’t want their office towers to be down-home, so Hines, who started as a mechanical engineer, has become the leading builder of Texas downtowns.

Tony Dorsett, Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, and Dallas. Started humbly, but he sure doesn’t want anybody to know it. Brags, struts, misbehaves, attracts attention, and otherwise comports himself in completely urban ways.

Erik Jonsson, Brooklyn, New York, and Dallas. Country boys don’t start computer companies, and when things are working according to plan, neither do they become mayor of Dallas. Jonsson did both.

Failed Country Boys

They try too hard, and it just doesn’t work.

Bill Hobby, Houston. Grew up rich and in the city, but because he runs a still-rural Senate, has to make a stab at countryness. As one country-boy lobbyist puts it, “He wears a big ol’ belt buckle, but he rides English saddle.”

Jim Wright,Weatherford and Washington, D.C. With the passing years, has begun to seem less and less Weatherford and more and more Washington, a pitfall that the old bulls of the Texas delegation always avoided.

John Hill, Breckenridge and Austin. Owns a ranch and otherwise tries hard, but somehow can’t pull it off. In the ’78 governor’s race, Bill Clements, born and raised in Dallas, seemed far more unsophisticated and elemental.

Jerry Jeff Walker, Oneonta, New York, and Austin. Presents himself as more Texan than Sam Houston, but isn’t simple, or modest, or respectful, which true country boys (Willie Nelson, for instance) always are.

Jimmy Carter, Plains, Georgia, and Washington, D.C. By all rights a potentially world-class country boy but was, in the end, ruined by his own hubris. He pretended for a while, but he was too preachy to aw-shucks successfully.

Dan Rather, Houston and New York City. Badly wants to be folksy, but his ego leads him down the path of pomposity. Unlike Walter Cronkite (a great country boy) Rather looks at the world with suspicion instead of wonder.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston