The Davy Crockett generation, those of us who once sported coonskin caps and fringed leather jackets, who endlessly wailed “Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee”—even though the real Davy Crockett was born in a valley—have now grown up and gone our adult ways. But few of us have forgotten that idyllic summer of 1955, when Davy’s life and death were endlessly replayed in countless back yards. Our teenage sisters may have swooned over Elvis, but we were transfixed by Fess Parker, who played Davy in Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier. He was tall and handsome, but more important, he always stood firm for truth and justice.

I was every bit as caught up in Davy mania as everyone else, and I suppose it was inevitable that I should eventually come back to the story of Davy Crockett and the Alamo. The Disney television programs and a wonderful Dell comic book entitled Davy Crockett at the Alamo had introduced me to history, and thus in a way were responsible for my becoming a historian. But a lot of illusions tend to fall away along the rocky road toward a doctorate in American history. I emerged jaded and cynical from graduate school in the mid-seventies. I wrote blistering articles debunking George Custer and a prizewinning biography of General Phil Sheridan that had not one good word to say about the main subject.

Finally, with the same acerbic spirit, I decided to take a look at Davy Crockett. This year, after all, is the two-hundredth anniversary of his birth. That seemed to be a good time to come to grips with the historical figure who had sparked my interest in history. If the truth be told, I wanted to dismantle him—to free myself from the shackles of childhood hero worship and prove once and for all my maturity and credibility as a scholar.

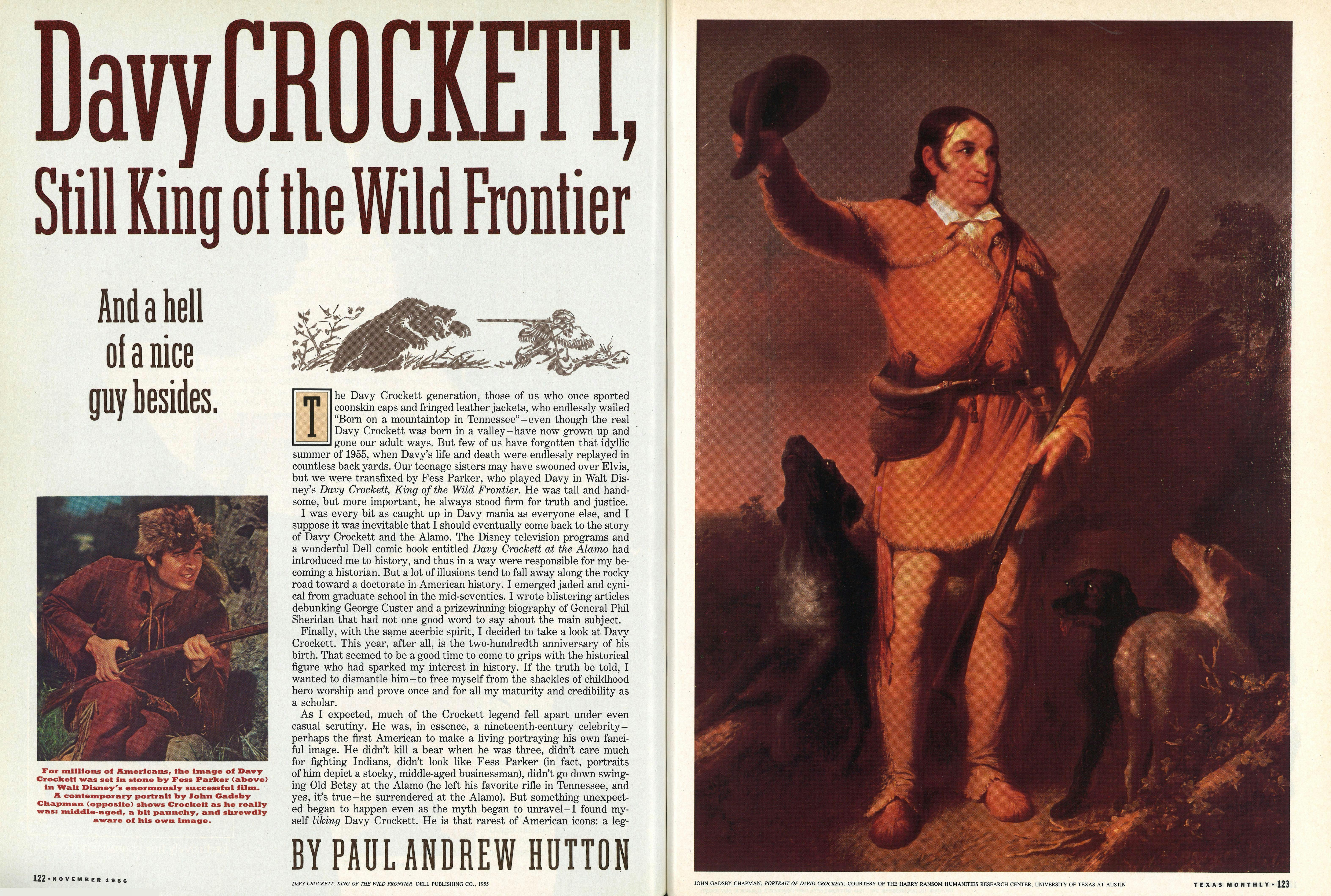

As I expected, much of the Crockett legend fell apart under even casual scrutiny. He was, in essence, a nineteenth-century celebrity—perhaps the first American to make a living portraying his own fanciful image. He didn’t kill a bear when he was three, didn’t care much for fighting Indians, didn’t look like Fess Parker (in fact, portraits of him depict a stocky, middle-aged businessman), didn’t go down swinging Old Betsy at the Alamo (he left his favorite rifle in Tennessee, and yes, it’s true—he surrendered at the Alamo). But something unexpected began to happen even as the myth began to unravel—I found myself liking Davy Crockett. He is that rarest of American icons: a legendary hero who turns out, after all, to have been more or less a decent, admirable human being.

David Crockett was born of dirt-poor pioneer stock on August 17, 1786, in what is now Greene County, Tennessee, just east of Knoxville. His grandfather and grandmother Crockett had been killed by Indians in 1777, and his father, John, had battled for American independence with other “over-mountain men” at King’s Mountain, North Carolina. Six or seven years after David became their fifth son, the Crocketts purchased a little log tavern on the road between Knoxville and Abingdon, Virginia.

Times were hard on the trans-Allegheny frontier, and children earned their keep. At twelve David was hired out as an indentured servant by his father to a rough Virginian. In 1802 he went to work as a farmhand to help pay off his father’s debts. About that time he began courting a local beauty but was rejected. That sobering experience convinced the forlorn youth of the power of education, for he had lost his love to a man who could read and write. After six months of hard schooling he again embarked on courtship and eventually won the hand of Polly Finley. They were married on August 14, 1806, and moved to a tiny rented farm.

They did not prosper, and in 1811 they moved west in search of free land, settling on the Mulberry fork of the Elk River, near the Alabama border. “In this time,” David related, “we had two sons, and I found I was better at increasing my family than my fortune.” Crockett proved more adept at hunting than at farming, for deer and bear were plentiful in the forests and cane- brakes of Tennessee. Not only did those beasts provide essential food to subsistence-farm families like the Crocketts, but their skins also were a marketable cash crop.

Crockett eventually won widespread fame as a hunter, killing 105 bears in one season alone. Bear hunting was hard, dangerous work, and the image of Davy Crockett, tomahawk and knife in hand, wrestling a behemoth into table meat is one of our strongest frontier images. This image is not altogether false, but Crockett was too savvy a hunter to get tangled up in such a situation very often. When it came to killing a bear, he did the prudent thing. He shot the beast from a comfortable distance.

Crockett’s hunting escapades were interrupted when, in August 1813, Creek Indians slaughtered some five hundred settlers at Fort Mims, Alabama. Along with other young men of his region, he responded with rage to the atrocity and joined the militia in answer to General Andrew Jackson’s call to arms. His service in the Indian war was not particularly distinguished, but he did often act as a scout because of his experience in the woods. Although his “dander was up” as a result of the massacre, he took little pleasure in fighting the Indians and found himself unsuited to the life of a soldier.

On November 3, 1813, he participated in the brutal massacre of the Indian population of Tallussahatchee. Crockett had little stomach for such one-sided slaughter, later noting that “we now shot them like dogs; and then set the house on fire, and burned it up with the forty-six warriors in it.” More than two hundred Creek men, women, and children perished before Jackson’s men reckoned that Fort Mims had been avenged and began to take prisoners.

The starving soldiers then searched the ruins of the Indian cabins for food, which led to an almost cannibalistic meal as related by Crockett. “It was, somehow or other, found out that the house had a potato cellar under it,” Crockett recalled, “and an immediate examination was made, for we were all as hungry as wolves. We found a fine chance of potatoes in it, and hunger compelled us to eat them, though I had a little rather not, if I could have helped it, for the oil of the Indians we had burned up on the day before had run down on them, and they looked like they had been stewed with fat meat.” Such stomach-churning work was a bit rough for Crockett, and as soon as his ninety-day enlistment was up, he headed for home, thus missing Jackson’s final triumph against the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend in Alabama on March 28, 1814. Although Crockett reenlisted as a sergeant the next September and scouted against British-armed Indians in the West Florida swamps, he was happy to leave martial glory behind him when his enlistment expired in March 1815. He would not again bear arms as a soldier except for thirteen days in 1836 at the Alamo.

No sooner was Crockett home than tragedy struck. Polly, although seemingly well after the birth of their daughter, Margaret, suddenly took ill and died in the summer of 1815. It was, as Davy wrote, “the hardest trial which ever falls to the lot of man.” He mourned awhile, but being a practical man, he soon began to look around for a new mother for his three young children. His attentions were directed toward a young widow, Elizabeth Patton, whose husband had been killed in the Indian war. Crockett could not help but take interest in her “snug little farm,” and admiring her two young children as well, he, as he put it, “began to pay my respects to her in real good earnest; but I was as sly about it as a fox when he is going to rob a hen-roost.”

They were married on May 22, 1816, and soon moved to the head of Shoal Creek in Lawrence County, Tennessee. It was there that Crockett began his political career, first as magistrate, then as justice of the peace, then as town commissioner, and in 1818 as colonel of the local militia regiment. In 1821 he was elected to the state legislature and was returned again in 1823.

Elizabeth, a frugal and industrious woman, watched over the farm while David hunted for bears and campaigned for votes. Endowed with a good measure of common sense, an uncommon streak of pure honesty, and a warm sense of humor, Crockett was a natural for the rough-and- tumble, down-home brand of backwoods electioneering. His strong defense of squatters’ rights in the western country won him good marks in the legislature, and others encouraged him to run for Congress. He was defeated in his congressional campaign in 1825 but came back strong in 1827 to win.

His campaign style was simple and direct, and it fit well in an era in which political meetings usually opened with a barbecue and ended in a dance, with the candidates expected to buy drinks for everyone. A wealthy friend, merchant Marcus Winchester, financed Crockett’s early political career, providing the Colonel with enough cash, as he put it, “so I was able to buy a little of ‘the creature,’ to put my friends in a good humor.” Crockett was, however, usually outfinanced in his campaigns and had to supplement cash with wit. This he had in plentiful supply. Since candidates traveled from town to town together giving stump speeches, they often became quite friendly and were well accustomed to each other’s style. On one occasion Crockett memorized his opponent’s speech and gave it word for word to the assembled crowd. That left the other candidate speechless and the audience convulsed with laughter. On another occasion Crockett’s opponent was a man, undoubtedly an ancestor of President Jimmy Carter, famed for “wearing upon his countenance a peculiarly good-humored smile.” Crockett worried that his opponent “may get some votes by grinning, for he can outgrin me, and you know I ain’t slow,” and to prove his prowess at grinning he told his constituents how he had taken to grinning coons out of trees. “Well, I discovered a long time ago that a ’coon couldn’t stand my grin,” the Colonel told the voters. “I could bring one tumbling down from the highest tree. I never wasted powder and lead, when I wanted one of the creatures.” Although Crockett left his buckskin hunting shirt back in Tennessee along with Elizabeth and the children, he quickly became a picturesque figure in Washington, winning renown as the canebrake congressman. Identified strongly with Andrew Jackson, who would win the presidency in 1828, Crockett quickly emerged as a symbol of the dawning age of the common man. His generation, the first to face the future without the guidance of the founding fathers, was an insecure lot who turned to the frontier in search of the values associated with the revolutionary era. They associated the West with unbounded opportunity, viewing Westerners like Crockett as the flag bearers of a “manifest destiny” that called for the God-ordained expansion of American institutions and culture clear across the North American continent. Crockett came to symbolize rough egalitarianism, freedom of opportunity, manifest destiny, and a regeneration of the cherished principles of the Declaration of Independence.

Some stuffed shirts, of course, were not impressed. Alexis de Tocqueville discovered Colonel Crockett in 1831 and was horrified: “Two years ago the inhabitants of the district of which Memphis is the capital sent to the House of Representatives in Congress an individual named David Crockett, who has no education, can read with difficulty, has no property, no fixed residence, but passes his life hunting, selling his game to live, and dwelling continuously in the woods.”

But Crockett was an incredible success as a celebrity. In 1831, after he had been reelected to a second term, one newspaper labeled him “an object of universal notoriety” and reported that “to return from the capitol without having seen Col. Crockett, betrayed a total destitution of curiosity and a perfect insensibility to the Lions of the West.”

The April 1831 New York premiere of James Kirke Paulding’s enormously successful play The Lion of the West gave quite a boost to Crockett’s fame. Actor James Hackett’s portrayal of the blustering but commonsensical Colonel Nimrod Wildfire was immediately recognized as a caricature of Crockett. At first the congressman was not amused, but as the play’s popularity grew, with the public warmly embracing Nimrod Wildfire as a distinctively American hero, his opinion changed. When Hackett appeared in Washington for a benefit performance of The Lion of the West in December 1833, David Crockett had a reserved box seat. When the buckskin-clad, fur-fcap-bedecked Hackett appeared onstage, he turned and studiously bowed toward Crockett. The Colonel rose and bowed right back.

The whole audience went wild.

If Paulding’s play had initially parodied Crockett, the congressman and his press agent soon returned the favor by imitating Nimrod Wildfire. It was Hackett as Wildfire who established the coonskin cap as Crockett’s symbolic headgear, for no contemporary portrait or written account identifies such a crown upon the King of the Wild Frontier’s regal head before 1835. The first drawing of Crockett in a fur cap (it is a wildcat skin) graces the cover of Davy Crockett’s Almanack 1837, and a copy of a drawing of Hackett as Nimrod Wildfire by Ambrose Andrews was used to publicize the play. Contemporary drawings of the real Crockett portray him with a broad-brimmed felt hat of the style popular in the mid-nineteenth century. Almost as famous as the coonskin cap was Crockett’s “half-horse, half-alligator” brag. But even that bold speech was plagiarized from Paulding’s play by Mathew St. Clair Clarke and attributed to Crockett in an unauthorized biography in 1833.

As successful as Crockett was as a celebrity—and he was one of the first Americans to make a living off his celebrity status—he was equally unsuccessful as a politician. During his three terms in Congress, Crockett failed to have one piece of legislation passed, including his squatters’ rights bill, which was meant to protect the right of Western squatters to purchase the land they had pioneered. He had two basic character flaws that doomed his political career from the start: he was just too independent and too honest to be a congressman, much less president. He proved to be unable to compromise on important issues and soon came to believe that President Jackson had ceased to support the interests of the common man. Crockett’s pet issues, such as squatters’ rights, ran against the interests of the wealthy planters and moneyed land speculators who were Jackson’s financial backers. His contention that government ought to “at least occasionally, legislate for the poor” met with studied indifference in Washington.

Crockett broke with Jackson toward the end of his first term in Congress and from that point on could be classified as an early Boll Weevil of the stripe that would make Phil Gramm right proud.

His most famous departure from the Jackson camp was over the notorious Indian removal bill. As passed on May 24, 1830, it appropriated $500,000 to move Indians living east of the Mississippi River off their ancestral lands and into the Indian Territory (Oklahoma). It is now viewed as one of the darkest blots on our history. Although Crockett realized that the bill was wildly popular with his pioneer constituents, his conscience told him that removal was immoral, and he boldly voted against it. Not totally naive, he arranged to have his speech in opposition to the removal bill excised from the published Register of Debates in Congress so as not to burden his constituents with having to read it.

Crockett’s independent streak became even more pronounced during his second term, and Jackson grew more irritated. Clearly, an example had to be made of this backwoods upstart, so Old Hickory’s men pulled out all the stops and achieved a narrow victory for their candidate, William Fitzgerald, in 1831. But after two years of hunting bears Crockett returned in 1833 to defeat Fitzgerald and win back his seat. Then came a period of vigorous image building, first with the publication of Crockett’s autobiography followed by his grand tour of Eastern cities in 1834. The Whigs were delighted with Crockett, hoping to use him as their backwoods common man and thus beat Jackson at his own symbolic game. As the party representing Eastern mercantile and industrial interests, however, the Whigs had little in common with Crockett’s philosophy. But his head was turned by their blandishments so that he came to believe their talk of running him for president in 1836. In 1835 the Whigs published two books, both ghostwritten by political hack writers but attributed to Crockett; one described Crockett’s Eastern tour, and the other was a bitter biography of Jackson’s candidate for the presidency, Martin Van Buren. Also in 1835 came the first of fifty Crockett almanacs that would be published before the series ended in 1856. Titled Davy Crockett’s Almanack of Wild Sports of the West, and Life in the Backwoods, 1835, the almanac carried a Nashville imprint and proved to be enormously popular.

Despite all the publicity Crockett received through his speaking tour, his autobiography, his ghostwritten books, and the almanac, the Whigs grew increasingly disenchanted with him. The Whig professional politicians could no more control or manipulate the independent Crockett than could Jackson’s men, so they began to distance themselves from him. Crockett’s 1835 defeat at the polls made the loss was a hard blow. He turned 49 in August 1835, the very month of his electoral defeat, and even with his fame his family was barely better off economically than when he had first won election as magistrate. Restless and embittered he looked about for some opportunity to rebuild his personal and political fortunes. The papers were full of stories about Texas, where American settlers were growing uneasy under Mexican rule and there was plenty of free land just waiting for a man bold enough to take it. Crockett’s old political rival Sam Houston had already gone to Texas to recoup his tattered fortunes and was doing quite well as an agent for American land speculators.

In October 1835 Crockett wrote that he was “on the eve of Starting to the Texes.” He was to be accompanied by three friends and hoped to “explore the Texes well before I return.” If word of the fighting that had broken out at Gonzales, Texas, on October 1 had reached Crockett, he made no mention of it, and it seems certain that he went to Texas to explore the land as well as the economic prospects, not to fight a war.

The little party left Memphis on November 2, 1835, traveling down the Mississippi River to the Arkansas River and thence to Little Rock, Arkansas. James D. Davis witnessed their departure and many years later remembered that Crockett “wore that same veritable coon-skin cap and hunting shirt, bearing upon his shoulder his ever faithful rifle,” the first contemporary mention we have of the famous cap. Crockett’s party moved slowly, exploring the Red River country, and finally entered Texas near Clarksville. Crockett was short of funds by this time and traded his engraved watch to a Red River farmer for a cheaper watch and some cash. Early in January they reached Nacogdoches. By then the war news was ominous.

This news was a tonic to Crockett, not because he relished battle, but because it meant that a new government was to be formed and he was likely to be part of it. He could not have come at a better time. The Mexicans had surrendered San Antonio to the Texan rebels on December 11 and had departed for the Rio Grande and points south. The time for fighting might well be over and the time for politicking just beginning.

In Nacogdoches Crockett swore an oat of allegiance “to the Provisional Government of Texas or any future republican Government that may be hereafter de dared.” He had the word “republican inserted before he would sign the oath. The citizens then held a banquet in his honor, and he regaled them with a wonderful speech: “I am told, gentlemen, that when a stranger like myself, arrives among you, the first enquiry is —what brought him here? To satisfy your curiosity at once as to myself, I will tell you all about it. I was for some time a Member of Congress. In my last canvass, I told the people of my District, that, if they saw fit to re-elect me, I would serve them as faithfully as I had done; but if not, they might go to hell, and I would go to Texas. I was beaten, gentlemen, and here I am.” The crowd roared with laughter and applause, and he was back into electioneering.

Crockett was in a buoyant mood when he wrote his daughter Margaret from San Augustine on January 9, 1836. He had joined the army and planned to set out in a few days for the Rio Grande with a band of volunteers. Still, he apparently did not anticipate battle, for he added: “But all volunteers is entitled to vote for a member of the convention or to be voted for, and I have but little doubt of being elected a member to form a constitution for this province. I am rejoiced at my fate. I had rather be in my present situation than to be elected to a seat in Congress for life. I am in hopes of making a fortune yet for myself and family, bad as my prospect has been.” It was clear he saw his role two months before his death as a politician, not as a soldier. “Do not be uneasy about me,” he closed. “I am among friends.”

On February 3, 1836, Crockett led a dozen companions —dubbed the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers —into San Antonio. Naturally, he was promptly called on to give a speech. “I have come to aid you all that I can in your noble cause,” he told the crowd. “I shall identify myself with your interests, and all the honor I desire is that of defending as a high private, in common with my fellow citizens, the liberties of our common country.” It was vintage Crockett, full of false modesty and common-man symbolism. The speech established him as a natural, democratic leader of the San Antonio garrison.

There was no shortage of leaders for the 150-man garrison, for both Colonel Jim Bowie, the legendary knife-fighter, and the ambitious young Lieutenant Colonel William Barret Travis competed for command of the outpost. But worries over military matters could be postponed, for no one expected Santa Anna’s army for at least another month or two. On February 10 a grand fandango was thrown in Crockett’s honor by the garrison, only to be interrupted by a scout’s report that the Mexican army had crossed the Rio Grande, just 150 miles distant. There was a hurried officer’s call, but everyone agreed that the enemy could not possibly be that near, so the dancing continued. Nobody seemed much interested in obeying the orders of the new commander of the Texas army, Sam Houston, to blow up the fortifications at the Alamo and abandon San Antonio. Crockett, of course, would hardly encourage any respect for the commands of his old political enemy.

So it was that the garrison was taken by surprise with the arrival of the Mexican advance guard on February 23. The Texans hurriedly retreated to the doubtful sanctuary of the crumbling Alamo. As the Mexican band serenaded the Texans, the Mexican army raised a blood-red flag, signifying no quarter. Crockett reported for duty to young Travis. “Colonel, here am I,” declared the old hunter. “Assign me to a position, and I and my twelve boys will try to defend it.” Travis gave him the rough log palisade between the Alamo church and the south wall, the weakest point in the defenses. Despite Crockett’s minimal experience as a soldier—in fact, he wisely hated war for the obscenity that it was—he rated the toughest assignment in the post on the basis of his already overblown legend. For the same reason, he could not leave San Antonio once the enemy was expected. He was trapped by his own legend and now must play out his string and trust providence to deliver him. If he survived, his political future in Texas would be secure, for status as a war hero was always worth a passel of votes.

But there was no escape from the deadly trap. Day after day the enemy ranks grew stronger, soon numbering nearly 5,000. Appeals for aid brought but 32 bold men from Gonzales into the Alamo on March 1. Powder and shot were in short supply, rations grew thin, and the weather turned cold. So did the spirits of the defenders of the Alamo. Crockett tried to cheer them with his fiddle and his smile, but even he grew weary. “I think we had better march out and die in the open air,” he told Susannah Dickinson on March 4. “I don’t like to be hemmed up.”

At five on the freezing morning of March 6, 1836, the Mexican assault finally came. Santa Anna threw his best 1,500 troops against the battered walls of the Alamo. Colonel Juan Morales led 100 men against the wooden stockade defended by Crockett and his boys. Twice the Mexicans were repulsed, but they eventually scaled the north wall and poured into the sprawling Alamo compound. The Texans, some 180 strong, were stretched far too thin, and it was all over quickly.

But not all of the defenders perished immediately, and here we must take note of the unavoidable reality of Crockett’s surrender. A few men, discovered hidden under mattresses in the long barracks, were taken prisoner. General Manuel Fernandez Castrillon, a brave and humane officer who had led the assault against the northeast wall, then halted the advance of his soldiers on another tiny band of exhausted, bloodied defenders. He offered them clemency and persuaded them to surrender. He gathered all the prisoners, numbering only seven, and marched them into the courtyard between the church and the long barracks. Crockett was among those men, although it is impossible to tell which group he belonged to. It is difficult to envision him hiding beneath mattresses, and so to soothe our psyches we can assume that he was with the band taken prisoner by Castrillon There is no doubt, however, that he was a prisoner, for numerous witnesses reported it. There is no eyewitness account of his death in battle, despite the wishful thinking of generations of writers and readers. The accounts of his surrender are by Mexicans and thus were ignored or discounted for more than a hundred years. Of those accounts, none is more reliable than that of Lieutenant Colonel Jose Enrique de la Pena, an officer on Santa Anna’s staff. According to De la Pena Crockett presented himself to Castrillon as a tourist who had taken refuge in the Alamo upon the approach of the Mexican army. It was not altogether an untruthful story, although it stretched reality a bit— but such is the politician’s craft. Crockett was no soldier, and in this hopeless situation an attempt to talk his way out makes perfect sense. It is not surprising that he did so, but it is surprising—knowing his gift of gab—that he did not succeed.

De la Pena described Crockett as a man “in whose face there was the imprint of adversity, but in whom one also noticed a degree of resignation and nobility that did him honor.” General Castrillon pleaded with Santa Anna for mercy on behalf of Crockett and the other prisoners, but the Mexican president ignored him. To Castrillon’s horror, a group of officers, eager to ingratiate themselves with Santa Anna, set upon the prisoners. De la Pena says that they were tortured before they were killed, though he spares us the details. He takes pains to point out, however, that Crockett and the others “died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.”

So perished Colonel David Crockett of Tennessee, bear hunter, congressman, and now, martyr on the altar of Manifest Destiny. He died as he had lived, boldly facing his opponents with unflinching determination—as his lifelong motto declared—to be sure he was right, and then to go ahead! Crockett did not fall in the height of battle, ringed by the men he had slain with his clubbed rifle and knife, but it is of no consequence. Such a death would have been out of character with his life. He was no warrior chieftain—no Beowulf or Roland—but rather a pioneer turned politician who came to symbolize Western egalitarianism and unbridled opportunity. He died in search of that opportunity, not lusting after the blood of his fellowman. That he who so represented the spirit of democracy should perish at the orders of a despot who cared for nothing but his own ambition is somehow fitting. It was a fine close to a magnificent career, and it secured a glorious immortality for Crockett that a successful political career in Texas never could have.

The real David Crockett may well have perished at the Alamo, but the legendary Davy Crockett was just beginning to live. The Crockett almanac, only two years old, continued to grow in popularity. The almanacs interlaced backwoods tall tales with information on the phases of the moon and weather predictions. Cheaply produced and illustrated with rough woodcuts, they were aimed at a wide popular audience. Crockett emerged in the stories as an American Hercules —wading the Mississippi, steering an alligator up Niagara Falls, straddling a streak of lightning, wringing the tail of a comet, and kicking the sun loose from its frozen axis.

The almanacs continued until 1856, and in later years they became mouthpieces for jingoistic expansionism. The Crockett of those final almanacs was horribly racist with a sense of humor that was chiefly excremental, sexual, and bigoted. It was a sad parody of the historical figure that revealed all too clearly the darker side of our frontier legends. Industrial America, however, took little interest in Crockett. After the Civil War, he remained a popular figure for boys’ fiction, usually in tales about the Alamo but little else.

A handful of movies featured Crockett, but by 1930 his stock as a hero was so low that Vernon Louis Parrington, in his classic Main Currents of American Thought, described him as “a true frontier wastrel.” Parrington found little to admire, seeing in Crockett and his frontier some of the worst American traits: “Strip away the shoddy romance that has covered up the real man and the figure that emerges is one familiar to every backwoods gathering, an assertive, opinionated, likable fellow, ready to fight, drink, dance, shoot or brag, the biggest frog in a very small puddle, first among the Smart Alecks of the canebrakes. Davy was a good deal of a wag, and the best joke he ever played he played upon posterity that has swallowed the myth whole and persists in setting a romantic halo on his coonskin cap.”

Parrington pretty well had the last word on Crockett for a decade, but then a group of writers interested in the origins of American folklore rediscovered Davy and rejuvenated the legend. Constance Rourke, Walter Blair, and especially Richard Dorson not only brought Davy out of hibernation, they created a new interest in the Crockett legend that has endured for more than forty years.

If Dorson had given birth to modern scholarship on Crockett and to the modem discipline of American folklore with his 1939 book Davy Crockett: American Comic Legend, it was Walt Disney, fifteen years later, who acted as midwife to the rebirth of Crockett as a full-fledged popular hero. On December 15, 1954, the first episode of a Crockett trilogy aired on the new Disneyland television series. “Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter,” was followed on January 26, 1955, by “Davy Crockett Goes to Congress,” and on February 23 by “Davy Crockett at the Alamo.” The shows were a spectacular success.

Disney was caught in the embarrassing position of having killed off his hero just as the Crockett craze began to sweep the country. He combined the television episodes into a ninety-minute film, Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, which he released in the summer of 1955. “The Ballad of Davy Crockett,” originally written as narrative filler for the television shows because there was not enough film footage, sold ten million copies and was the number one record for thirteen weeks.

An unprecedented merchandising bonanza followed. Raccoon tails, selling for 25 cents per pound in 1954, jumped to $5 per pound as American kids demanded their very own coonskin caps. The caps were the biggest merchandising item, but Disney also licensed three hundred other products to carry the official Crockett label—toy guns, buckskin suits, powder horns, tricycles and bicycles, towels, soap, wallets, pajamas, pillows, bedspreads, toy soldier sets, games, lunch boxes, and even ladies’ underwear. A Boston store owner stuck with three thousand pairs of unsold moccasins labeled them Davy Crockett moccasins and sold them in a week. But after six months—the zenith was in May 1955—the Crockett craze declined. That was good news for raccoons but bad news for retailers stuck with millions of unsold coonskin caps.

Although Davy has not again enjoyed the media limelight as he did in 1955, he was kept before the public as a result of John Wayne’s 1960 film, The Alamo, and two controversial books, one by Carmen Perry and the other by Dan Kilgore, in the seventies. The casting of Wayne as Crockett was inspired: an American icon portraying an American icon. The reviewer for Time thought Wayne the definitive Crockett, “the natural ignoble man invested with the authority of size and the dignity of slow wits.” In the film Wayne’s Crockett dies by blowing himself up with the Alamo’s powder magazine. This spectacular end is based on nothing more than a screenwriter’s fantasy, although such an attempt is attributed to Alamo defender Robert Evans.

Of course, there were those who claimed Davy did not die at all. After the fall of the Alamo, the Crockett almanacs kept up a steady stream of reports of his captivity deep in the interior of Mexico, where he was forced to work the mines as slave labor. Only rapid American expansion—of which Davy Crockett now became a vital symbol—could save him. Other tales had him hunting for pearls in the South Seas and trapping grizzlies amid the misty heights of the Rocky Mountains. It became common knowledge in those days that the Colonel was roaming the Great Plains with his pipe-smoking pet bear, Death Hug. They would boil their buffalo meat over prairie fires, escape from tornadoes by riding streaks of lightning—pausing only to swallow a thunderbolt—and quench their thirst by drinking up the whole Gulf of Mexico. Eventually a pet buffalo called Mississip was added to the troop because his fine bass voice complemented the colonel’s tenor so nicely in nightly songfests around the campfire.

So maybe Davy escaped from the Alamo after all. I, for one, never actually saw him die. I saw him in that final episode of the Disney TV show swinging Old Betsy, clubbing enemy soldiers right and left, but I never saw him die. There was a fade to the Lone Star flag as the last verse of “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” came onto the sound track, but Davy definitely never went down. In my San Angelo back yard, he always won the battle of the Alamo.

I can understand the reluctance of those who refuse to accept the story of his surrender. Everybody wants to keep Davy up there where he belongs, swinging Old Betsy from the ramparts of the Alamo. And at least one cynical historian is inclined to believe the best about him. Maybe he didn’t go down fighting, maybe he couldn’t even grin a coon out of a tree, but he was a talented, self-made man who fought for human rights and democracy and was defeated in politics because of his independence and honesty. At the Alamo he fell in defense of his vision of freedom, whatever the details of his death.

If Davy Crockett is still alive, up there in the topmost Rocky Mountains cavorting with Death Hug, Mississip, and the rest of his critters, I for one hope he has a happy two-hundredth birthday. After all, he’s earned it.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Davy Crockett