New States of Convenient size, not exceeding four in number, in addition to said State of Texas, and having sufficient population, may hereafter, by consent of said State, be formed out of the territory thereof, which shall be entitled to admission under the provisions of the Federal Constitution…

—From the Joint Congressional Resolution providing for admission of Texas to the Union, 1845.

Bob Gammage, the freshman state senator from Houston’s south side, sips coffee at his desk in the Bellfort Legal Center and thinks that one over. “The strongest argument in favor of it in my mind,” he says, “is that it would give us a great deal more clout on the national scene. We would automatically increase from two to ten U.S. senators.”

Gammage and his friend Dan Kubiak, a state representative from Rockdale, may introduce a resolution to carve up the state when the legislature meets this month. People have been talking about that for better than a century but obviously nobody has gotten around to making much headway. Gammage and Kubiak lofted a trial balloon during the constitutional convention last summer. Now, the first thing anybody asks when you propose to divide the state is, “which way are you going to divide it?” So Kubiak and Gammage, who are less interested in drawing lines than in kicking the idea around, had to come up with a Plan.

One of their states was called North Texas; it extended from the Dallas-Fort Worth area all the way to the New Mexico border. A Lubbock newspaper immediately opined that being in the same state with Dallas had been bad enough when there was only one state to be in; keeping the two together after a division would add insult to injury. That is the problem with offering your Plan; everybody starts finding things wrong with it and wants to talk about their Plan instead.

That, in a nutshell, has been the problem all along, ever since Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845 under the widespread expectation at home and in Congress that division, as it came to be called, was only a matter of time. If a random Rip Van Winkle among the Texas leaders who approved that Joint Congressional Resolution should suddenly awaken in Austin today, he would be astonished that only one state with one capital existed. Throughout the lifetime of anyone who remembered the War for Texas Independence, division—some time, some way—was simply taken for granted.

Between the 1840s and the 1920s, not a single decade passed without some halfway serious effort in that direction. More than once, division missed by no more than a hairbreadth.

Isaac Van Zandt, a popular Democrat, ran for governor in 1847 on a platform calling for immediate division into four states. He seemed headed for victory, but he died. So did his division plan.

Conflict between East and West Texas simmered throughout the 1850s. The 1852 House considered—and finally defeated, 33-15—Representative Peter Flanagan’s resolution to split the state along the Brazos River.

Flanagan was back again in the constitutional convention of 1866 with another resolution to segregate 38 counties east of the Trinity River into the “State of East Texas.” This time he got no farther than a favorable committee vote, but the Radical Republicans were listening; when they got rid of the Confederate-tainted leaders and began Reconstruction in earnest, division was at the top of their agenda.

Tantalized by the knowledge that five separate states would mean five times as many offices to occupy and five stockpiles of patronage plums to distribute, the carpetbag/ scalawag delegates to the 1868 Constitutional Convention set to work chopping and slicing maps in every direction. The only thing that prevented prompt division was disagreement over how it should be done. Of all the plans, the one that came closest to adoption called for division into just three states—“East Texas,” “Texas,” and “South Texas.” It used the Trinity and the Colorado rivers as the boundary lines. This so-called “Congressional Plan” would have bisected Travis County and turned Austin into an obscure country town; it would also have severed Houston and Galveston from their natural East Texas hinterlands.

Proponents of the plan declared that, among other things, “it embodies the highest wisdom in giving Seacoast to each state as a base for offensive and defensive purposes.” Other delegates favored surgery in different directions, and a few thought Governor Elisha Pease had the right idea when he suggested selling the Panhandle and the Trans-Pecos to the U.S. government for an Indian reservation. Even though a majority of delegates favored some sort of division and succeeded in passing a general resolution to that effect, parliamentary jockeying produced a stalemate.

Radical Republican Governor E. J. Davis pushed hard for division plans in the 1871 legislature. One of these, the four state idea submitted by Representative Robinson of Bowie County, comes closer than anything else in the long succession of division plans to making sense a hundred years later (see illustration).

The Radical Republicans’ self-serving fervor for division succeeded in giving the idea a bad odor for the rest of the century. Nevertheless, division talk surfaced in Texas or in Congress in 1888, 1906, and 1909, with prohibitionists doing most of the talking the last time around.

West Texas discontent over the legislature’s failure to reapportion itself after the 1910 census, coupled with the feeling that too few state institutions were being located out there, produced an abortive effort to create the “State of Jefferson” in the 1915 legislature. Even the critics of that plan, like the Austin-American, were still calling division “inevitable” sooner or later.

Governor Pat Neffs 1921 veto of a bill creating “West Texas A & M College” produced the last brief flare-up of division sentiment. For a few days the spirit of sedition reigned in, of all places, Sweetwater. But the outcome was just a manifesto of grievances, not a divisionist crusade.

The five states idea became the personal property of John Nance Garner over the next decade, who occasionally pulled it from the closet and rattled it, skeleton-like, at his colleagues in the U.S. House of Representatives who showed too little respect for the Power of Texas. It seems to have died with him; Texans who reached maturity after the Second World War think of division only as a historical curiosity, if they think of it at all, never realizing that it was a lively and recurring theme in their state’s first hundred years. Oh, the late San Antonio Senator V. E. “Red” Berry, an advocate of pari-mutuel gambling, proposed division into North and South Texas in 1969 to protest his northern colleagues’ opposition to horse racing—but neither Berry nor anyone else took his resolution seriously.

Senator Gammage himself is an appropriate person to bring it back. His ancestors came to Texas in the days of the Republic; his great-grandfather served in the 21st Legislature; and the walls of his office are decorated with yellowed family land grants. Acknowledging that Texas has been kept all in one piece as much by sentiment as by politics (“Who will give up the blood-stained walls of the Alamo?” typified the cries of nineteenth-century opponents), he thinks a divided Texas should remain a “commonwealth.” By that he means any division plan should provide in advance for placing such things as the university system, the dedicated funds, and the rich public lands under a single administration. Each new state would draw a proportional share of what is now public land revenue, and each would contribute proportionally to services, like education, that would operate in common. This done, the new states could go their separate ways on everything else. The plan has a lot of obvious bugs to be worked out, Gammage admits. But he thinks it would bring government “closer to the people” and have just as much sentimental value as the present boundaries: “Now that the Republic is gone I have no difficulty identifying with any other political entity that might take its place.”

Gammage is careful to disclaim any serious intention—for now—to take up where Garner left off. “For the time being it’s a tongue-in-cheek idea with me,” he says. “But the more I think about it the more rational it seems.” And though he expects the public reaction to be negative at first, he has a feeling that the idea just might catch on. “The ordinary Texan feels used and exploited by Eastern finance; this would be sort of a political equalizer.”

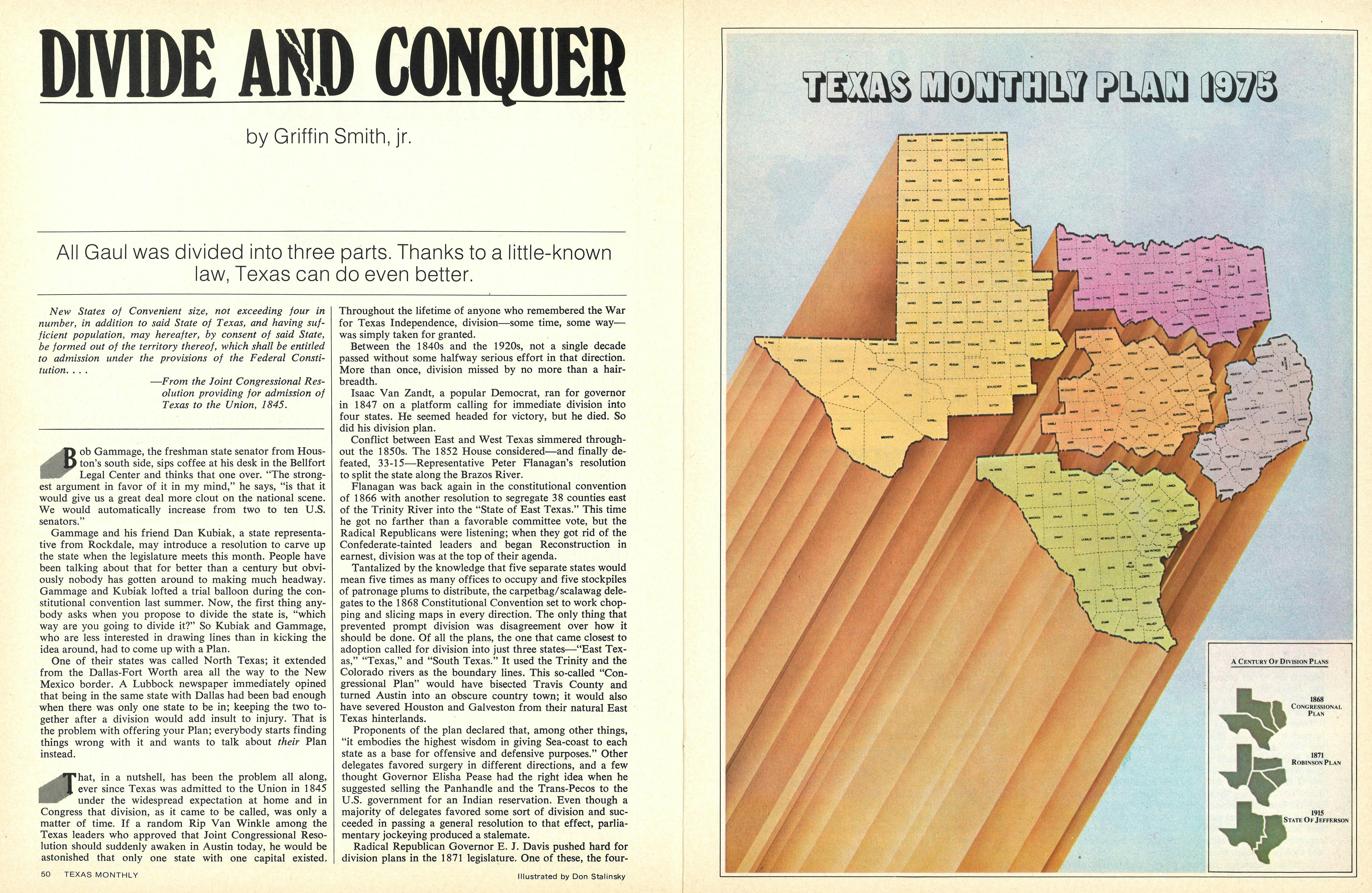

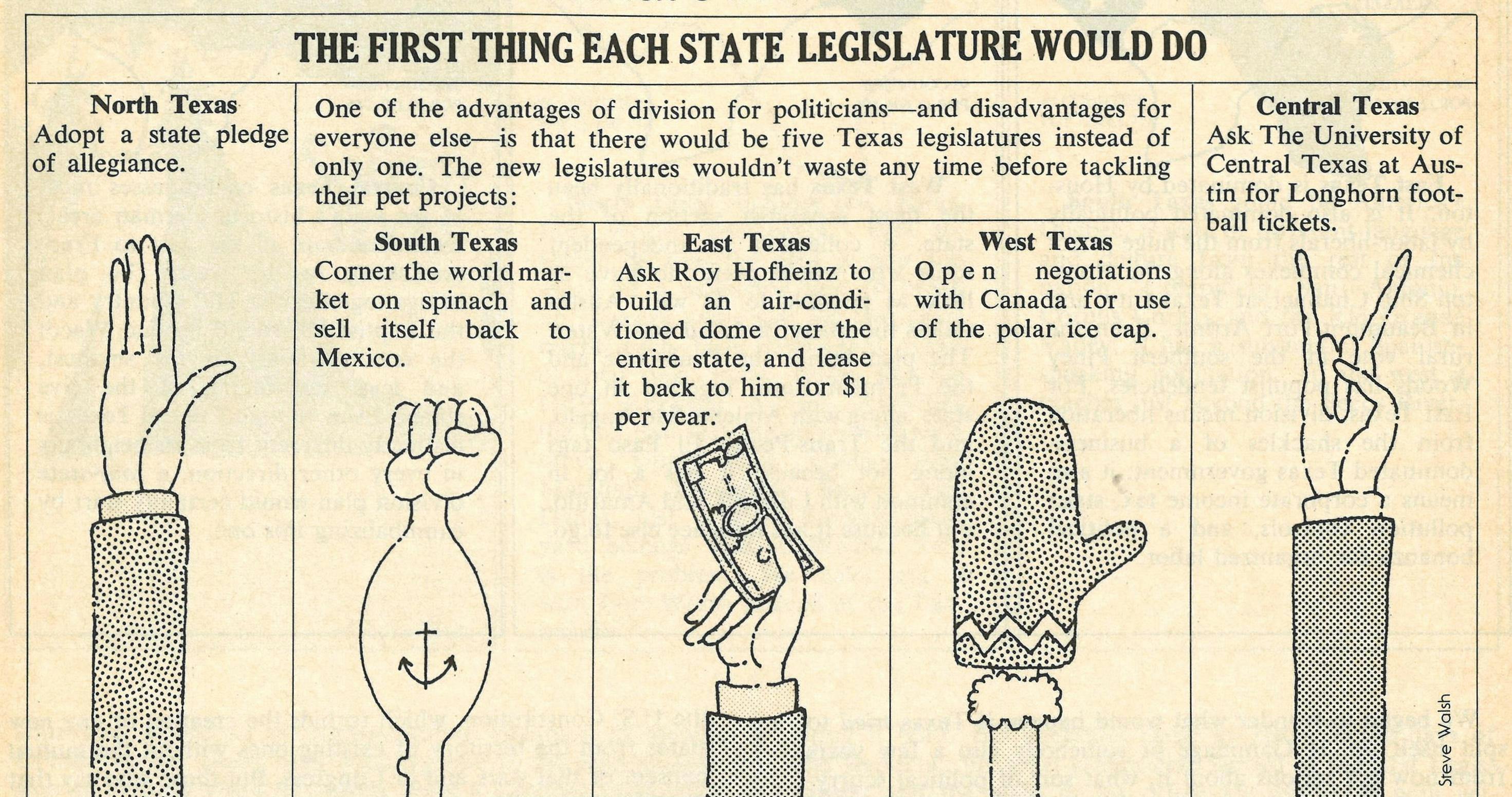

One afternoon when the editors of Texas Monthly were sitting around feeling used and exploited by Eastern finance, we pulled out a road map and started dividing Texas up ourselves. The result, after some gerrymandering and several days of haggling between factions, is the five-state plan here.

We began to wonder what would happen if Texas tried to split itself up. If Gammage or somebody else a few years from now got serious about it, what sort of political scurrying and shaking would arise?

Any division plan would meet with determined opposition from the Lobby, which presently has things comfortably in hand. Texas’ vast distances virtually insure that a candidate for statewide office must have better than a quarter million dollars before even considering a race, and a million has sometimes not been enough for victory. There are not many places to get that. The impact would be felt first in Houston, where industrial interests that have always counted on legislators from the boondocks to protect them from corporate income taxes and other schemes attractive to Southeast Texas’ predominantly liberal electorate would suddenly find themselves boondockless. “The establishment would be terrified,” chuckled former State Senator Don Kennard.

But if the Legislature somehow overcame all that, passed a resolution dividing the state, and sent a copy to Congress with a note saying, “We decided to take you up on that offer you made last century; please arrange for eight more desks in the Senate”—what then?

“I think 49 other states would drag us straight into the Supreme Court of the United States,” says Gammage, grinning impishly. “They’d be scared to death of the clout we’d have in the Senate.”

Scholarly opinion is divided over whether the 1845 Five States Clause would be upheld; one of the strange things about the whole century-long discussion is that nobody has ever tried very hard to resolve the potentially thorny legal questions. Was the clause valid at the time? Did the Civil War change anything? How about Reconstruction? If Texas finally decides to divide, does Congress have to consent again?

If the Supreme Court ruled against the division of Texas, it would probably give as its reason Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution, which forbids the creation of any new states from the territory of existing ones without the mutual consent of that state and of Congress. But those who say that the Five States Clause was, and remains, perfectly constitutional simply argue that Congress has long ago given its half of the required consent, and all that’s left is for Texas to go ahead and act.

Gammage is sure of one thing. If Texas did try to divide and the Supreme Court said no, things could really get interesting. The old Republic gave up its sovereignty with the understanding that it could divide at will—there is absolutely no doubt about that—and if the Articles of Annexation that allowed this are unconstitutional, then Texas might legally be an independent Republic again.

“When the courts deal with questions of constitutionality,” he says, “the unconstitutionality of just one part of a law doesn’t nullify the whole law—provided the law includes a ‘severability clause.’ If there is no severability clause, one unconstitutional part automatically nullifies the whole subject. I find no severability clause in the Articles of Annexation. So under their own precedents, if they said the portion granting Texas the right to divide was unconstitutional, then the entire document would be unconstitutional. And Texas would revert automatically to the status of an independent republic under the Constitution of 1836.”

James Nance, the reigning expert at the Texas Legislative Council’s informal committee to study division of the state, agrees. “Texas agreed to join the Union on those terms,” he says. “If Congress couldn’t offer them, why then there wasn’t any meeting of the minds. Legally, everybody knows you couldn’t have an agreement like that without a ‘meeting of the minds.’ That’s fraud.”

So oil-rich Texas may, it seems, have the United States over a barrel. Give us ten senators, or we join OPEC.

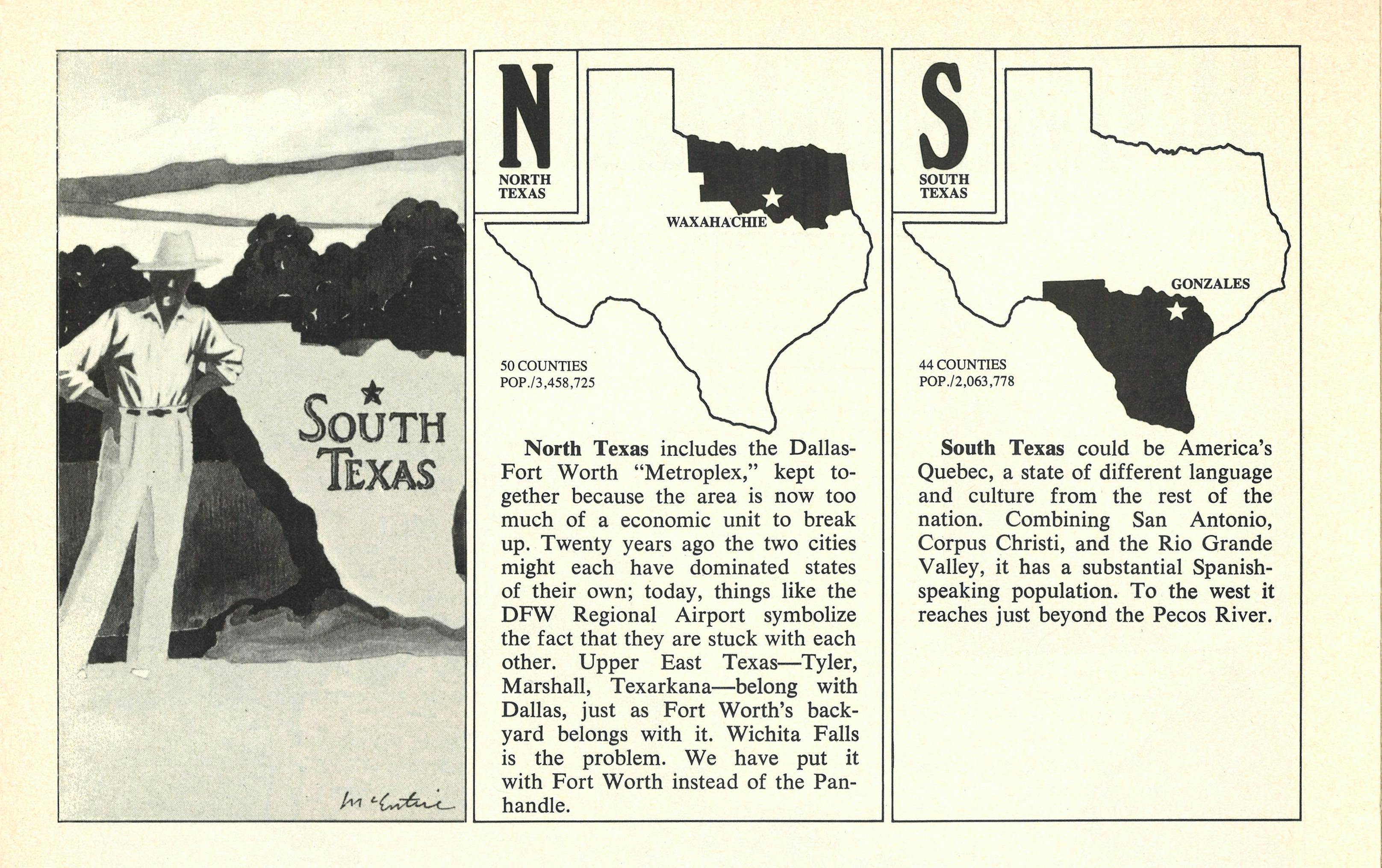

North Texas includes the Dallas- Fort Worth “Metroplex,” kept together because the area is now too much of an economic unit to break up. Twenty years ago the two cities might each have dominated states of their own; today, things like the DFW Regional Airport symbolize the fact that they are stuck with each other. Upper East Texas—Tyler, Marshall, Texarkana—belong with Dallas, just as Fort Worth’s backyard belongs with it. Wichita Falls is the problem. We have put it with Fort Worth instead of the Panhandle.

South Texas could be America’s Quebec, a state of different language and culture from the rest of the nation. Combining San Antonio, Corpus Christi, and the Rio Grande Valley, it has a substantial Spanish-peaking population. To the west it reaches just beyond the Pecos River.

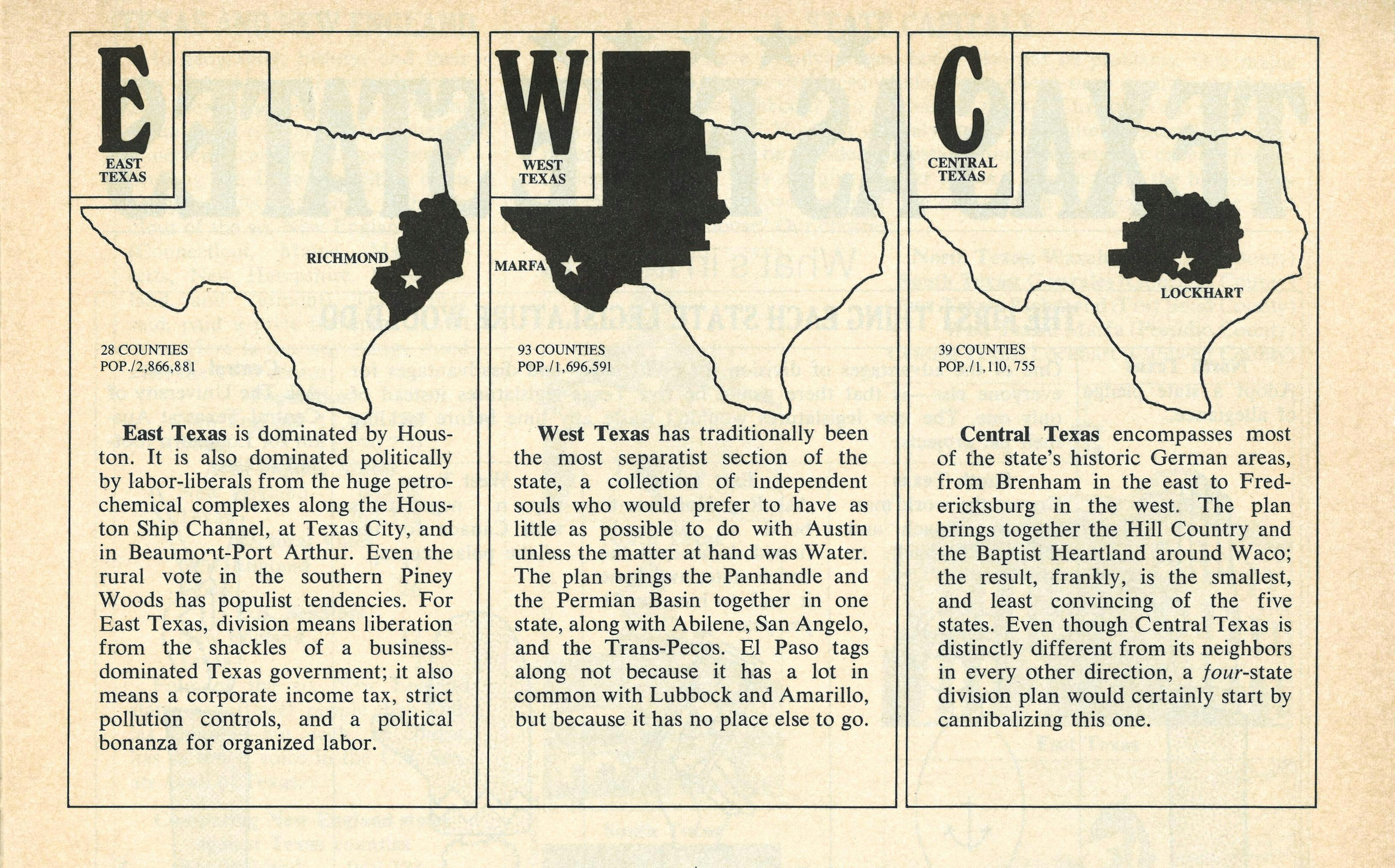

Central Texas encompasses most of the state’s historic German areas, from Brenham in the east to Fredericksburg in the west. The plan brings together the Hill Country and the Baptist Heartland around Waco; the result, frankly, is the smallest, and least convincing of the five states. Even though Central Texas is distinctly different from its neighbors in every other direction, a four-state division plan would certainly start by cannibalizing this one.

West Texas has traditionally been the most separatist section of the state, a collection of independent souls who would prefer to have as little as possible to do with Austin unless the matter at hand was Water. The plan brings the Panhandle and the Permian Basin together in one state, along with Abilene, San Angelo, and the Trans-Pecos. El Paso tags along not because it has a lot in common with Lubbock and Amarillo, but because it has no place else to go.

East Texas is dominated by Houston. It is also dominated politically by labor-liberals from the huge petrochemical complexes along the Houston Ship Channel, at Texas City, and in Beaumont-Port Arthur. Even the rural vote in the southern Piney Woods has populist tendencies. For East Texas, division means liberation from the shackles of a business- dominated Texas government; it also means a corporate income tax, strict pollution controls, and a political bonanza for organized labor.

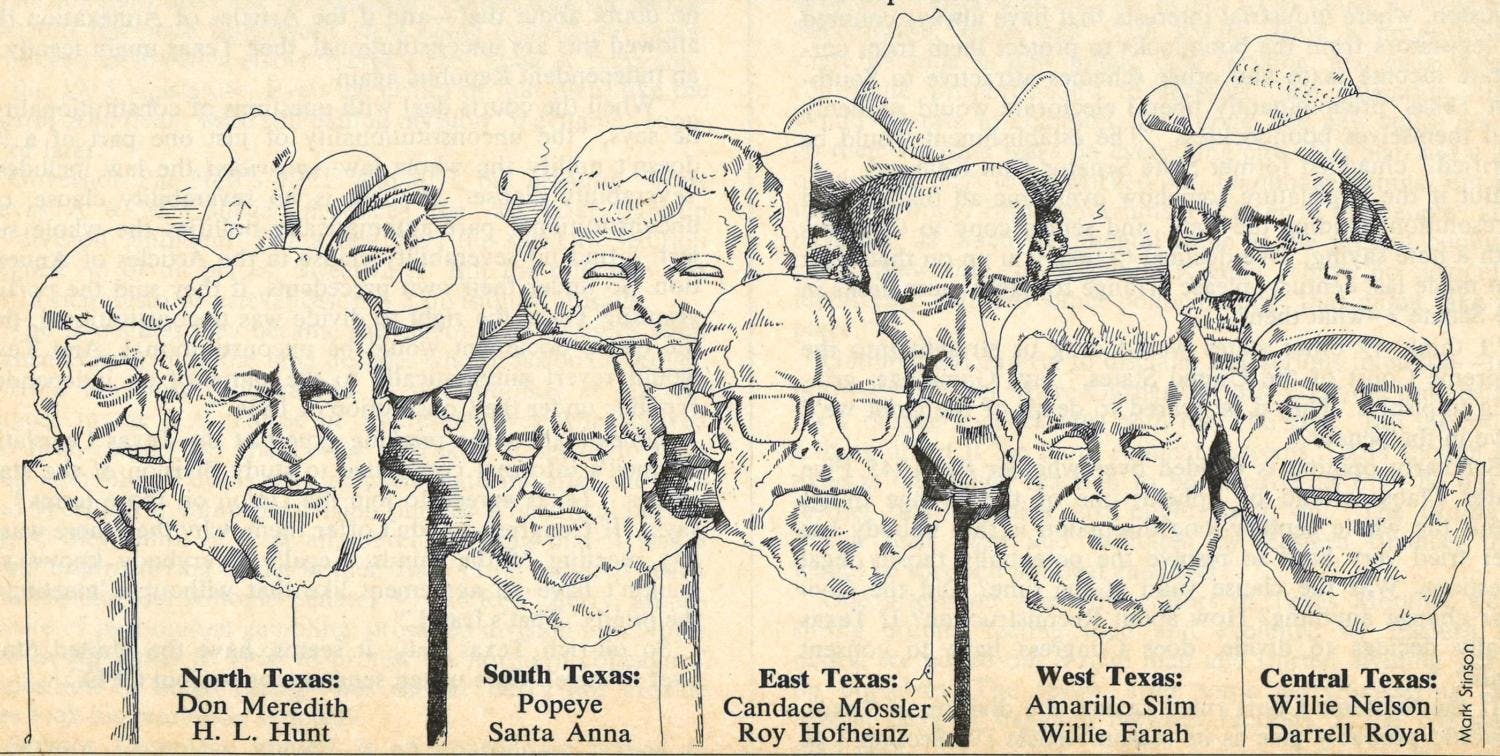

HALL OF HEROES

In 1864 Congress designated a portion of the national Capitol as Statuary Hall to commemorate notable public heroes from all walks of life. Each state was invited to erect two statues there to honor the men and women who epitomized the character of their state. After the end of the Civil War and the admission of new western states, the hall became overcrowded, and one statue from each state was moved elsewhere; but the tradition of honoring the heroes who symbolize their states continues. The five new states could contribute the heroes depicted below:

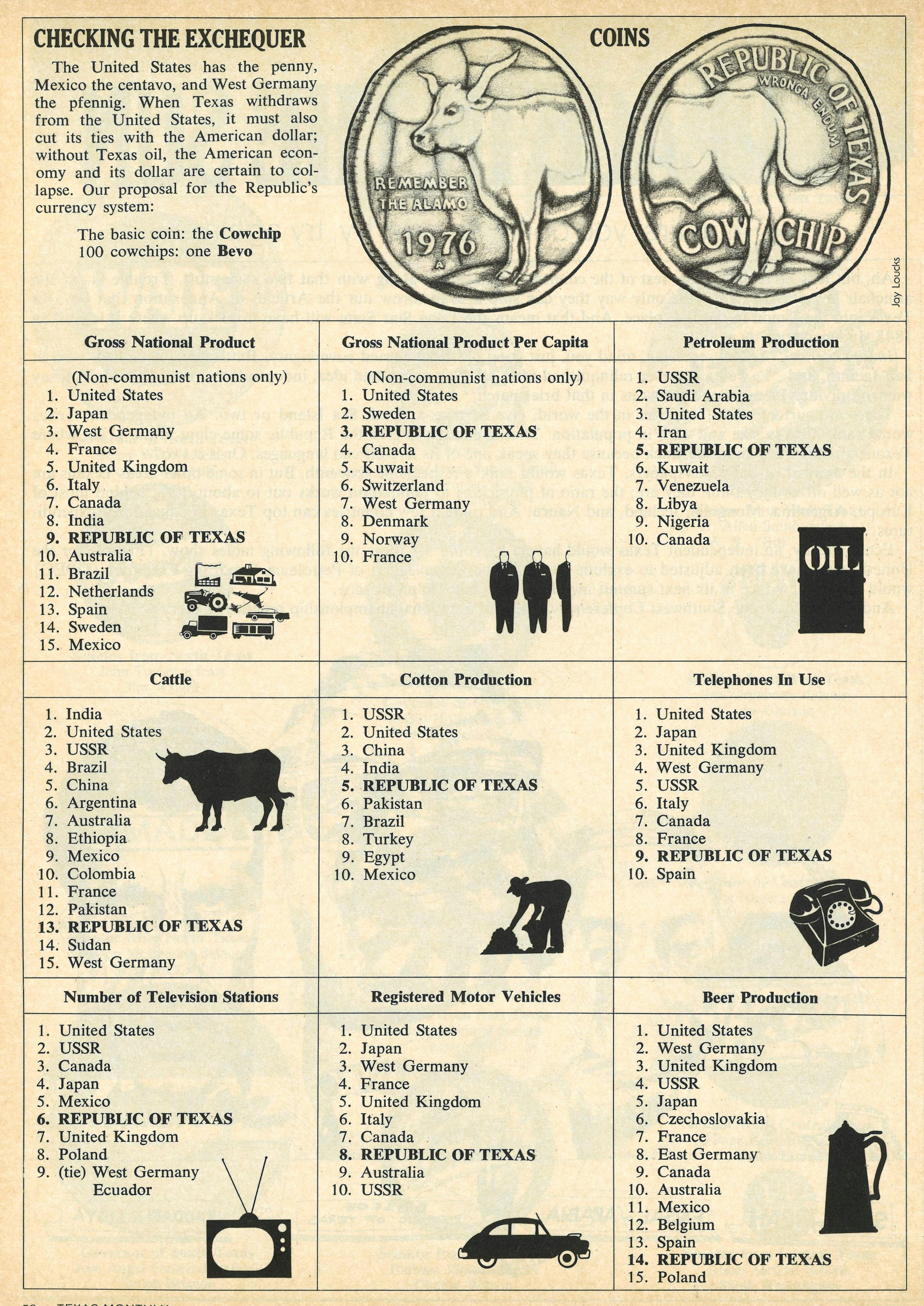

TEXAS AND NEW ENGLAND

In geography, history, and their way of looking at the world, Texas and New England are as different as any two regions of the country. Nineteenth-century proponents of dividing the Lone Star State often compared its influence with the clout of the six New England states (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont). Texas, they said, paid a price for unity. It still does. Here is the way things stood after the 1970 census:

Population

New England: 11,847,186 vs. Texas: 11,196,730

Area (Square Miles)

New England: 66,608 vs. Texas: 267,338

Electoral Votes

New England: 37 vs. Texas: 26

U.S. Senators

New England: 12 vs. Texas: 2

Four of the six New England states have fewer people than Dallas County—but each, of course, has as much voice in the U.S. Senate as all of Texas.

Comparing New England states against Texas counties

Rhode Island: 949,723 vs. Bexar County: 830,460

Vermont: 444,732 vs. El Paso County: 359,291

New Hampshire: 737,681 vs. Tarrant County: 716,317

Maine: 993,663 vs. Dallas County: 1,327,321

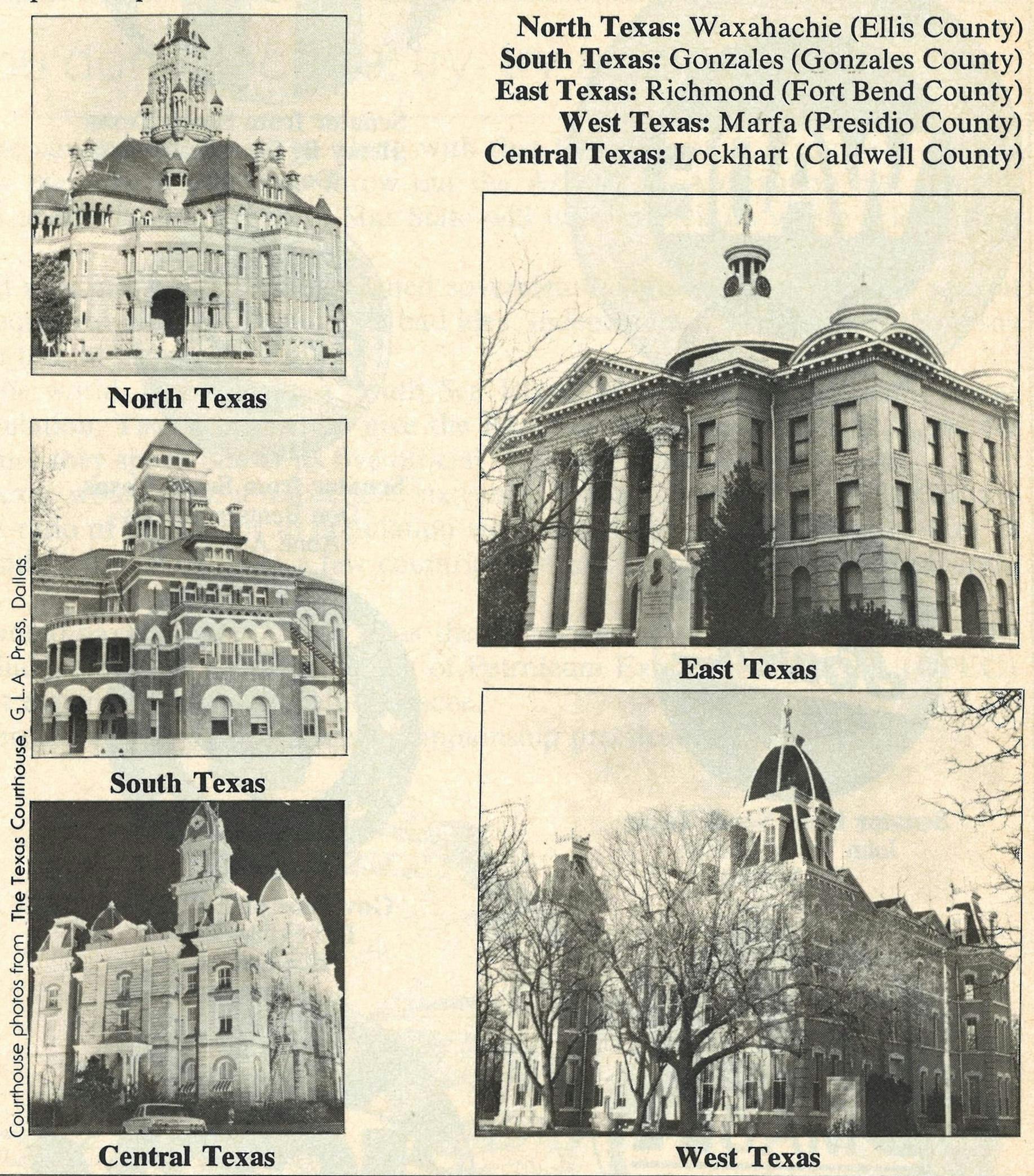

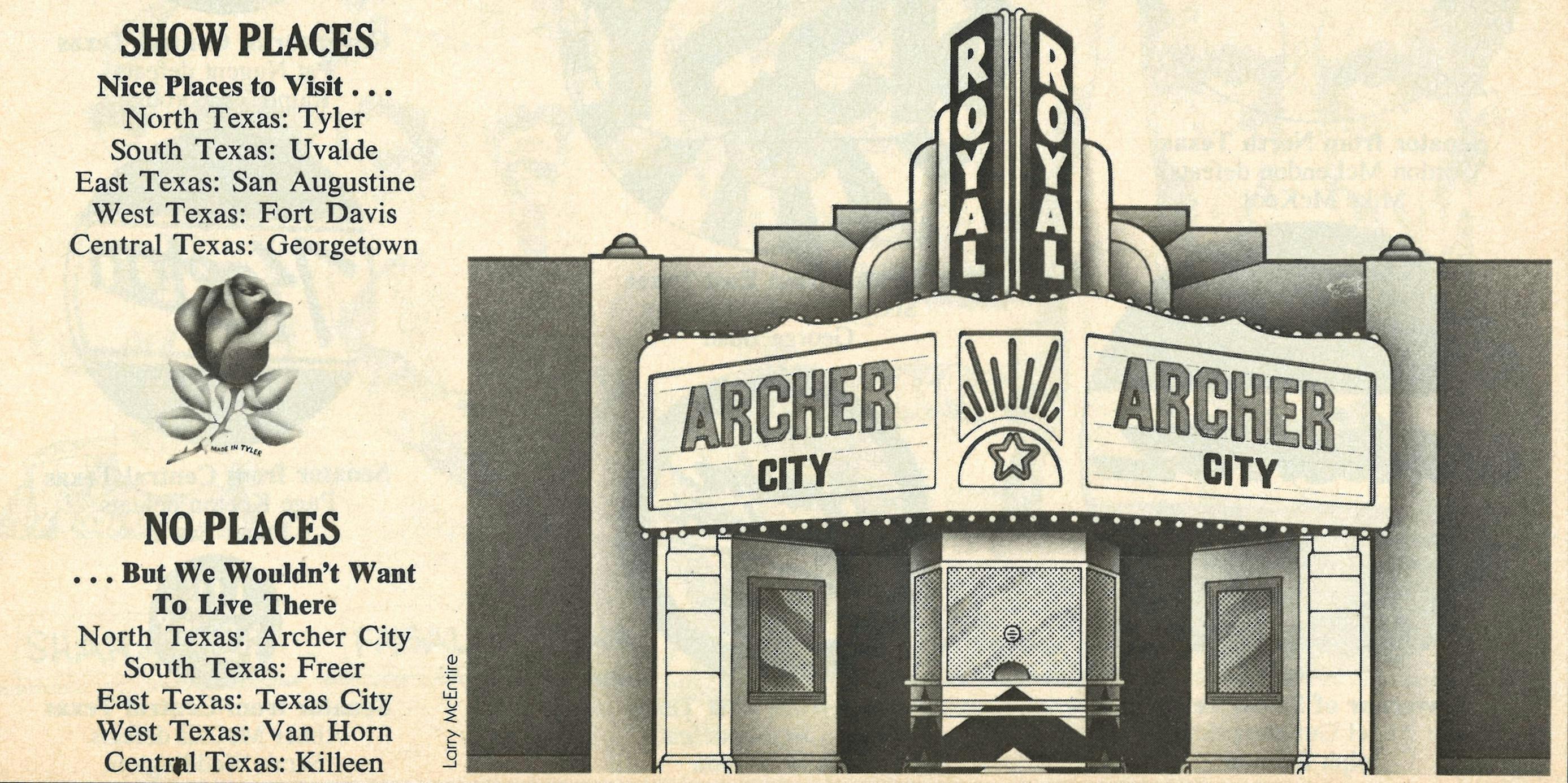

STATE CAPITALS

Division may have its advantages, but it also has its problems. One major obstacle will be the inevitable squabbles over where state capitals should be located. El Paso or Lubbock? San Antonio or Corpus Christi? Waco or Austin? Dallas or Fort Worth? Houston or Galveston? This bitter factional strife between rival cities can be avoided by establishing independent criteria for selecting the capital. Why not give smaller towns a chance to hit the big time by awarding the seat of government to the city in each new state with the most picturesque courthouse? Our choices:

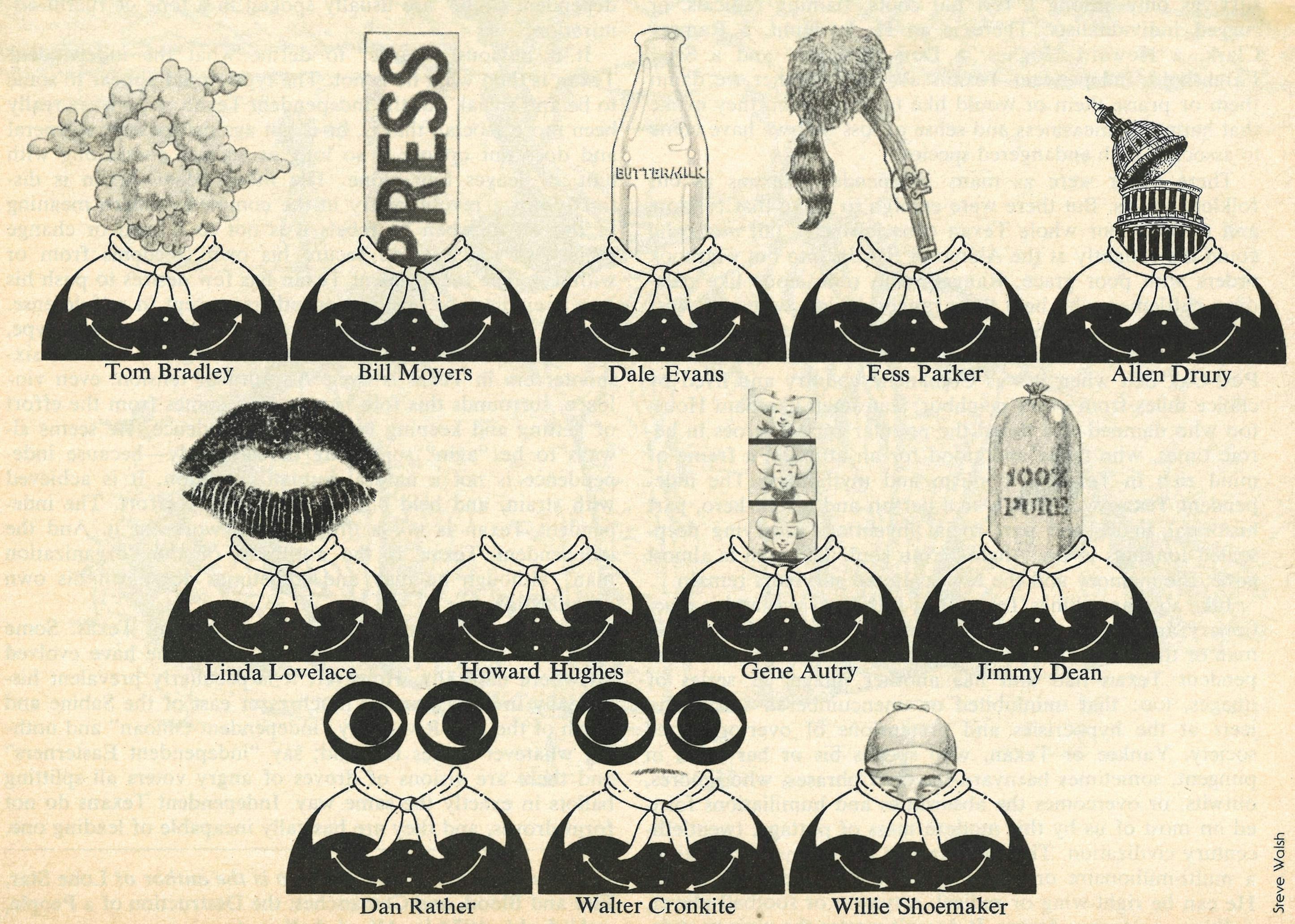

ADVISE AND CONSENT

The leaders of the new Republic must convince important and influential Texans to contribute their time and talent to the new nation. They should have little trouble recruiting Lady Bird Johnson to become Secretary of the Interior, or Frank C. Erwin, Jr., to head the Alcoholic Beverages Board, but many other positions will be harder to fill. In some cases President Briscoe may have to appeal to the national pride of Texans living abroad in places like New York and California; in rare instances he may even have to create new government positions to lure these “closet Texans” back to their native land. The government should include:

Minister of Security: Walter Cronkite (Houston)

Minister of Insecurity: Allen Drury (Houston)

Air Quality Board: Tom Bradley (Calvert)

Plenipotentiary: Bill Moyers (Hillsboro)

Secretary of Offense: Dan Rather (Wharton)

Meat Inspector: Jimmy Dean (Plainview)

Chief of the Bureau of Missing Persons: Howard Hughes(Houston)

Minister of Affairs: Linda Lovelace (Bryan)

Doorkeeper at the Alamo: Fess Parker (Fort Worth)

Pony Express Commission: Gene Autry (Tioga), Dale Evans (Uvalde), Willie Shoemaker (Fabens)

- More About:

- Texas History