El Paso and the Borderlands

By David Dorado Romo

From “A River Runs Through It,” originally published in June 2010

Growing up I had no idea of the multiple layers of meaning connected to the places I passed through every day. The layers opened up slowly. One such place was the Santa Fe Street international bridge, which links El Paso to Juárez. In many ways this binational thoroughfare best captures the essence of the fragmented city I’m from, a city originally called El Paso del Norte (the Pass of the North) that was later split in two along the Rio Grande. As a kid, going back and forth across the river was no big deal. We did it several times a week—to visit friends and relatives, eat at restaurants, and buy groceries in Juárez. For me the bridge was just a way to get to the other side of a muddy river. But as I look back, I realize that even then I could already sense that this narrow strip of concrete had deeper layers.

My earliest memory of crossing the Santa Fe Street bridge from Mexico into the United States took place when I was about five years old. I was in the backseat of my father’s Mustang. When we reached the checkpoint, my parents took out their U.S. residency passports and showed them to the customs agent. The stern-looking man stuck his head inside the car window, pointed his finger at me, and asked: “Citizenship?” I wasn’t sure what he was asking, so I took off my Mickey Mouse hat and waved it in front of his face.

As an adult I still have trouble answering questions at border checkpoints. For some reason interrogations always make me feel guilty. Plus I find it difficult to answer the profound existential questions the customs agents pose at these crossings: Who are you? Where are you from? Where are you going? Why? They’re the sort of queries I’ve never been able to answer truthfully in five hundred words or less. I always simply answer “American” to the citizenship question. But what I really want to say is that I’m a fronterizo. I’m from both sides.

Behind the Pine Curtain

By Prudence Mackintosh

From “The Soul of East Texas,” originally published in October 1989

It did not occur to me until I read William Humphrey’s 1965 novel The Ord-ways that my forebears in East Texas were the less adventurous of the Texas pioneers. Humphrey describes them this way: “Mountain men, woodsmen, swampers, hill farmers, they came out into the light, stood blinking at the flat and featureless immensity spread before them, where there were no logs to build cabins or churches, no rails for fences, none of the game whose ways they knew, and cowered back into the familiar shade of the forest, from there to farm the margins of the prairie like a timid bather testing the water with his toe.”

Cowering back into the familiar shade? Timid bathers? Could I still boast of being a fifth-generation Texan if my great-great-grandfather Samuel Corley had eschewed the vast and lonely Texas prairies to ride a Presbyterian circuit from San Augustine to the Red River? On the other hand, if the Corleys had charged on westward, their horses might have given out in Fort Stockton. I might have learned to sit a horse, but I would have missed the trees, the sandy-bottomed swimming holes, the hiding places, and the mystery indigenous to East Texas.

Historians have suggested that the trees in East Texas blocked our vision and walled us off from the outside world. From a child’s perspective, trees were simply an integral part of our games. How could a kid in Fort Stockton play a serious game of Tarzan or Swiss Family Robinson or even hide-and-seek without thick trunks, vines, and pine-needle carpeting? My mud pies were baked with mulberries or wild cherries. Chinaberries were ammunition. The partially exposed roots of an old oak tree could provide shelter for dolls or trolls or small plastic Indians. Magnolia trees offered totally enclosed play spaces, sturdy climbing limbs for even the smallest children, and cones with magic red-lacquered seeds.

San Antonio

By John Phillip Santos

From “City of Dreams,” originally published in June 2010

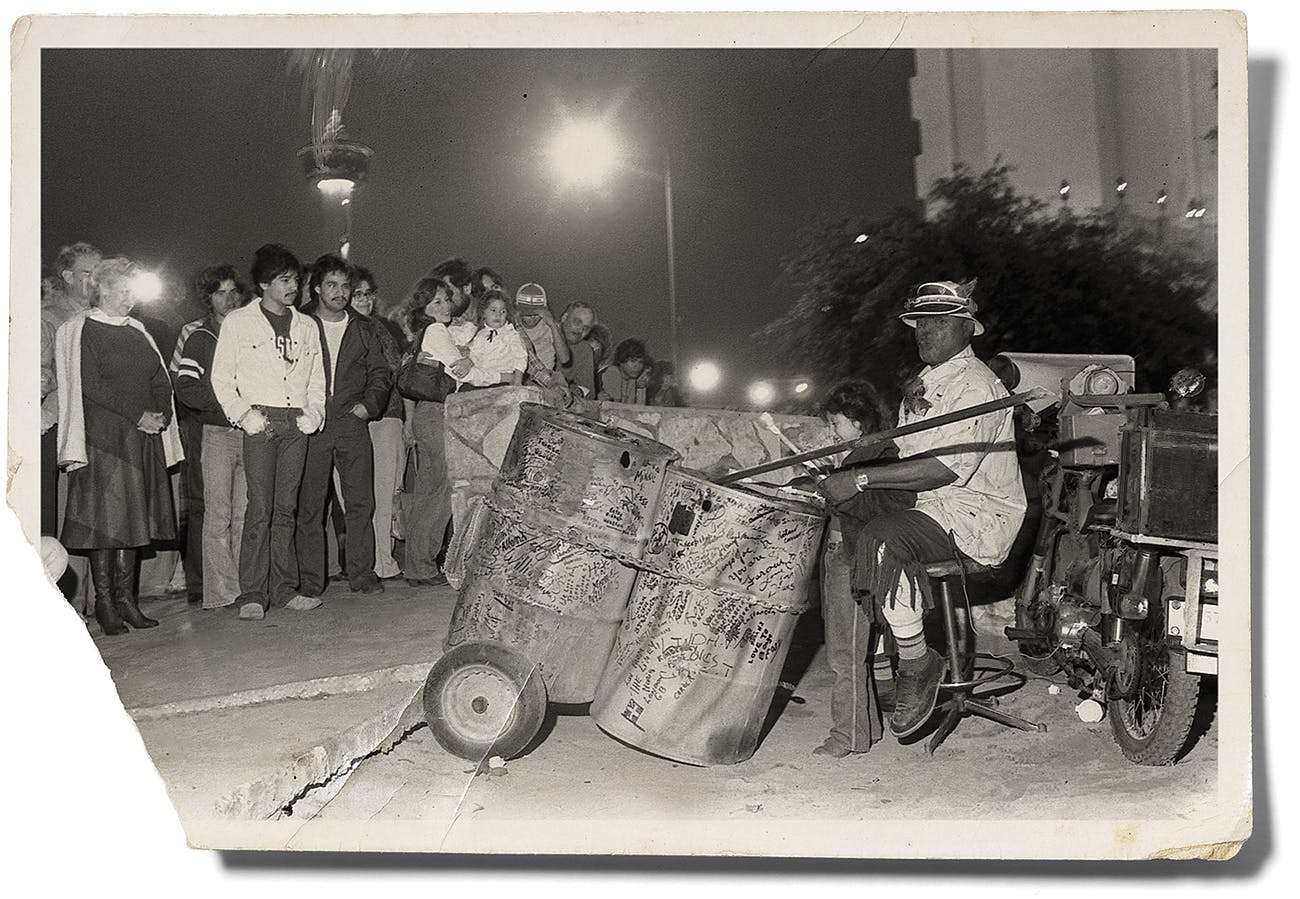

The city I discovered as a child was not the Alamo City of history books. For my twin brothers and me, the hoary limestone Alamo was where my parents would drive us many evenings, in pajamas, after the ten o’clock news, to hear the funky ruminations of Bongo Joe (a.k.a. George Coleman). San Antonio’s legendary African American street griot beat contemplative, slow-grooving, rock-steady batucadas on two battered oil drums with mallets he’d festooned with rattles that sounded as if they contained the teeth of defeated conquerors, echoing off the facade of the old Spanish mission. His drums were spray-painted in Day-Glo pink and chartreuse stripes.

Eventually, Bongo Joe was moved away from the Alamo—along with his wheelbarrow, where you could leave him coins or, better, bucks—elbowed over to a noisy intersection on Commerce and Alamo streets, where we’d have to strain to hear his poesía callejera de San Anto over the bustle. Recalling Bongo Joe today, I remember how his performances left me imagining the Alamo, and San Antonio, as places where everyone, from anywhere in the world, could conjure their stories, their poetry, their rhythms, their music.

Pampa in the Panhandle

By Anne Dingus

From “This Land Is My Land,” originally published in January 1988

Landmarks aside, Pampa has little to do with my memories. The country held all the romance. We chased down tiny horny toads the size of a man’s thumbnail and caged them in matchboxes until someone took pity on them and set them free. We had one as a pet once, Horatio, whom we housed in a shoebox and kept alive until the tragic day he was dispatched by his own dinner of red ants. Another pet was Cowboy, a tarantula so named for his bowlegged stance. He occasionally broke free of his pickle jar and terrorized my mother’s bridge club.

And, naturally, we had the weather. The dryness of the climate gave us a lifelong appreciation for rain, and in wet weather we danced about outside till we were soaked. The unceasing wind never bothered us, and coming from the right direction, it could be relied upon to provide one heck of a swing ride. At night while it whined we told ghost stories in our bunk beds. If the wind picked up during the day, Mother would pin quilts to the clothesline, and we would huddle in this makeshift cabin and pretend we were hardy pioneers. Sometimes the sky would turn a weird yellow, and a sandstorm would fling tiny needles right through the walls and eventually bring the whole playhouse tumbling down. Then we pioneers would make a break for the back door, where just inside we would pour a cup or two of grit out of our shoes before Mother would let us all the way in.

- More About:

- San Antonio

- Pampa

- El Paso

- East Texas