This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It’s a familiar sensation and it hits us in unexpected ways, without regard for station—as you’ll see in these interviews. Sometimes it is as ordinary as a child crawling on his grandfather’s lap and remembering years later that moment when life seemed complete. Or it can haunt the atavistic recesses of our psyche as it did the Jewish mother from Laredo who went in search of her own biological parents. We see it and note it in common places: a devoted mother and a precocious child, a family sing-along, a relationship so in sync that its participants finish each other’s sentences. Our search for meaning is a search without end, for an object with no name. But we know it when we see it.

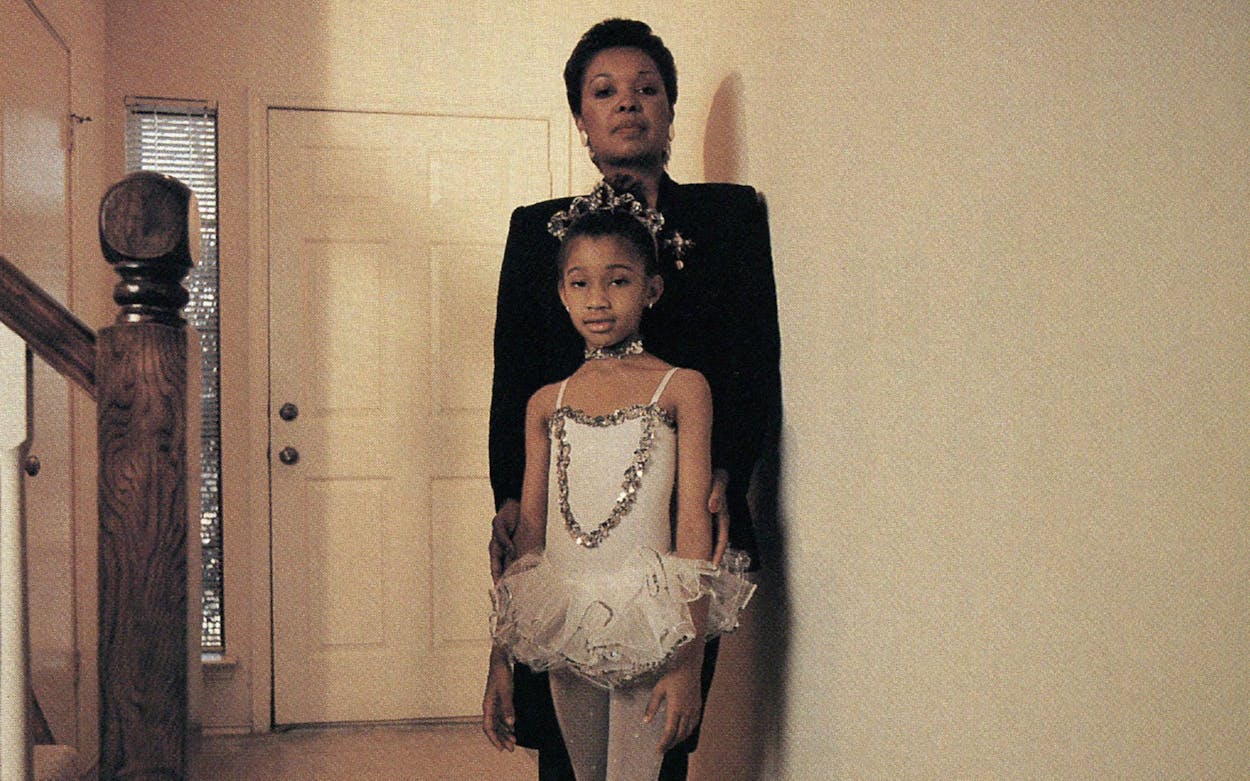

Sheilah Tucker

P.R. Consultant

Dallas

Raised in Seattle in an integrated environment and educated at the University of Washington, Tucker, 38, got her first look at the South (and her first encounter with racism) in 1972, when she came to Dallas as a stewardess for Continental Air Lines. Divorced since 1983, she devotes almost all her spare time to caring for her eight-year-old daughter, Kristin. Stylishly dressed, Sheilah Tucker sits in the living room of her well-furnished condominium in North Dallas on a Saturday morning, a Bible and copies of Ebony and Jet on the coffee table. Strategically placed around the room are pictures of Kristin in her school dress, her ballet costume, her new hairdo, etc.

I really never thought of racism until I moved to Dallas in ’72. I remember I had bought a new car, an MG, and the car salesman took me to lunch and people could not eat for staring at us. And I said, “Gosh, what’s wrong?” and he said, “People here are just not used to this.” Initially when I got here and started looking for an apartment, I was defensive. When someone told me they didn’t have a vacancy, I wondered if they were saying it because I was black. But later I realized that the people I encountered were some of the friendliest I had ever met, much more than when I was based in Los Angeles.

I do P.R., sales promotions, copy writing. I also write commercials and work with events, coordinating them. It’s kind of frightening being a single parent and being out there on your own. All of my relatives are on the West Coast, so there’s not a lot of people I can call and ask them to go pick up Kristin because she’s sick and I can’t leave work. It’s all on my shoulders. But things have been fairly good lately, and I’ve had time to do volunteer work and participate in activities with my daughter.

Kristin has to be at school at eight-fifteen, so I get up early and drive from North Dallas to South Dallas, which takes about 30 minutes, 45 if it’s raining. Then I have to drive across town again to get to my job. She is in the after-school program, so I pick her up again at five-thirty in the evening. Sometimes I wonder if I can take this drive another year, but she enjoys the school, and if she’s happy there, I don’t want to move her.

Kristin has always grown up in a predominantly white environment. When she started kindergarten at North Dallas Day School, she was the only black in her class. I don’t think she had any perception of race until an incident at the day school. She and I have a very good relationship—I encourage her to tell me everything—and she came home one day and told me that one of the little girls in her class told another little girl, “Don’t play with Kristin because she’s black.” It was like someone cut me apart. I’d never had that experience growing up in Seattle. I was trying to protect my child and hated for her to feel something must be wrong with her. And I said, ”Look, Kristin, some people don’t understand that God made all of us. He made everything, different color flowers, different type plants, different trees, everything, and nothing is alike. So next time someone says that to you, say, ‘I’m a little girl and you’re a little girl, and I just happen to be black and you just happen to be white, so what difference does that make?’ ” And later Kristin and this little girl became really good friends.

Kristin has always been the top student in her class, but her creative talents really blossomed last year. She started writing poetry, became a member of the girls club, and then a cheerleader. She was the teacher’s helper, she would help the principal. She reads all the time. I mean, she’ll pull out a book before she turns on the television. I don’t have to encourage her to read or study or do her homework; she just does it because she loves it. People are always telling me how great she’s doing, how she’s Miss Popularity at school and everyone wants to sit next to Kristin. And I know they’re saying this because —well, it’s true, but they’re also saying it because she’s black and she’s the top student in her class.

Social life? What’s that? No, not really. Every summer Kristin goes to Los Angeles and stays with my sister, and I have the whole summer to catch up. But it seems like the more time I have, the more I get involved with volunteer work for different clubs or my sorority or my church or the children’s ministry. Kristin is in the children’s choir at our church, and I work with that group and with the PTA and the cheerleaders and the booster club. I’m just everywhere. But I enjoy it. I’m happiest when I’m really busy and making a contribution.

Sheri Connell

Cindy Garzonie

Beauticians

McAllen

Cindy, 41, owns Kut ’n Kurl beauty shop, and Sheri, 31, works there. They have been friends for twelve years and are so in tune with each other that their conversation is like a well-rehearsed play, interrupted by frequent peals of laughter.

SHERI: I went to high school with the son and daughter of Cindy’s husband’s boss, and they told me that the shop was looking for a hairdresser.

CINDY: I was working for a man named Elvis.

SHERI: It was just three chairs—very small. I thought they had been forewarned that I was coming, but they hadn’t. Cindy looked at Elvis and said, “I don’t care if she can cut hair or not. Hire her.”

CINDY: That’s what I said. Sheri was leery of me for about three weeks—I was older and everything. Then one day we were alone in the shop together, and she said, “Cindy, can I ask you a question? Why do you wear your earring double-pierced in your right ear?” And I said, “Well, Sheri, it’s because I sleep on my left side.” and she said, “Oh, thank God! Do you realize that if your right ear is double-pierced, that means you’re a lesbian?” That was why she had been staying clear of me. After that we got to be real good friends. I don’t know if we can read each other’s mind or if it’s just that we’ve worked together so long, but our senses of humor click.

SHERI: I’ll make a comment that I may have made three years ago, and Cindy knows what I’m talking about. We’ll be standing here, working away, and she’ll say, “Well, did you get on the flight?” And it was a conversation we had a week ago that we never finished, and I just pick right up on it.

ClNDY: We play this game of funniest time in your life—

SHERI: Worst date, best date—

ClNDY: All that kind of stuff.

SHERI: It’s like this weekend we were in San Antonio for a convention with this other girl who’s not tuned in to us. Well, Cindy has this problem of falling in and out of the best bars in town—

ClNDY: Sheri!

SHERI: And she fell down twice in San Antonio. And I practically fell down laughing. I mean, she had injured herself—

ClNDY: I’m a klutz. I fall in and out of places. Sheri’s rolling around laughing and—

SHERI: And Jamie, this other girl, is asking if we need to call an ambulance.

ClNDY: No, I’ll get up eventually.

SHERI: I wanted to kill her back in March or April—

ClNDY: April tenth.

SHERI: She fell and broke her arm, and her husband came to my door and said, “Cindy needs to talk to you.” And I said, “It’s raining; my hair’s going to get wet.” And he said, ”But she needs to talk to you.” So I go over there and I see her, and I just start laughing.

ClNDY: It doesn’t upset me that she laughs, because it’s really stupid, me being such a klutz. I don’t know why our friendship has lasted, but maybe it’s inspiration on your part, Sheri. I need a friend.

SHERI: We’ve been through a lot together: her separation, divorce, remarriage. She lost her father—

ClNDY: She lost her father and stepdad—

SHERI: My father and stepdad, me getting married, having a baby. I didn’t have morning sickness; she did.

SHERI: It used to aggravate him how we could work together eight or ten hours a day and then go home and spend an hour on the telephone. And I’d say, “There are some things we just can’t talk about at the shop.”

D. D. Lewis

Ex–Pro Football Player

Dallas

The former Cowboys linebacker is now a sales representative for a large agri-industrial firm. A sixth-round draft choice out of Mississippi State in 1968, Lewis was a long shot to make it in the NFL. Yet he played fourteen seasons for the Cowboys; his 27 play-off appearances are still a league record. Never a star, Lewis was one of the durable, dependable athletes at the core of the Doomsday Defense, which dominated the NFL during the seventies. He retired after the 1981 conference championship game against the 49ers—remember the last-minute Montana-to-Clark touchdown pass that broke the hearts of Cowboys fans and denied the team a record sixth Super Bowl appearance? The end of the road for Lewis was, coincidentally, the end of the magnificent era of the Cowboys. Looking trim and fit again after a post-retirement jag, Lewis, 44, recalls the bitterly dark, almost suicidal days that followed his retirement.

I had been around and watched a lot of people leave the game, and I was prepared to retire. I’d saved money, I’d made good investments. Spiritually, psychologically, monetarily, I was ready to get out of the game—I thought.

Then I went into a depression. I had a farm up there in Wylie, and I stayed there. I laid in bed all day with the covers over my head.

I had thoughts of suicide, and it scared me to death. I thought I was crazy. I can’t explain the dynamics of what it was, only that I played football for 26 years of my life and all of a sudden it was over.

I made a Miller Lite commercial and I was making appearances for them and signing autographs, but I still had all this time. I ended up staying up at that farm and shooting skeet and trying to fish and drinking.

When the team went back to camp, I couldn’t believe they were doing it without me. Finally, I said, Well, heck, man, why don’t you use the experience you received from the Cowboys and go out and promote yourself? So I got a job in the oil-field supply business, selling pipe. Hi, I’m D. D. Lewis! They’d let me in just to see what I looked like without a helmet. But the oil business was in a slump, and there were thousands of pipe salesmen. Everybody said it was coming back in 1985, so I figured I’d get in there, make a name for myself, get a lot of contacts, and when it came back in ’85, make a lot of money. But it was worse in ’85 than in ’82 when I signed on.

So ’85 came and the bottom fell out and I went on and did other things. I went through a divorce, and it was devastating. It was something I never thought I’d ever go through. Here I was forty years old and I’d never lived alone. My mother took care of me until I went off to college, the school took care of me until I graduated, and then I went and got married and my wife took care of me for seventeen years. I never knew who I was; I had no identity to speak of. I was broke, I was in pain, I was afraid, my self-esteem was at a low. I had to start over again.

But I came out the other side. A friend offered me a job with the company I’m with now. It was a lifesaver. Conagra, that’s our big parent company—flour, grain, prepared meats. I’m in their fertilizer division, and my territories go from just north of Austin all the way to Louisiana and New Mexico. It was like a shot in the arm. I could be driving that highway, feeling depressed and poor me-ing, and it wouldn’t take anything for me to start thinking grateful thoughts. Man, look at this—they’re paying me to drive out here in rural Texas, the most beautiful state in this universe! Look how green it is, look at that field of wheat over here; it’s beautiful. And I’m not on a big four-lane highway, I’m on the secondary highways, going by grain elevators and feed stores. It’s usually a mom-and-pop operation and I’m selling them fertilizer and I don’t even mention fertilizer. I don’t know anything about corn or wheat or ryegrass or rotation and I’m asking the most stupid questions and these people are loving me, accepting me, and some of them don’t even know who D. D. Lewis is.

I got married again August 11, and it’s been the best experience I’ve had in a long, long time. I ran into my old college sweetheart, a girl I’d dated for two and a half years. She’d been married twice and divorced. And we started dating again and then got married. I feel whole again. I think God meant for us to be with a mate. Landry used to say that life’s a struggle and the great thing about life is working through our adversities. Well, it’s true. It’s facing challenges and going through them and getting on the other side.

Debbie Salamon

Shop Owner

Laredo

With her Israeli-born husband, Uri, Debbie owns and operates Arco Iris, a fabric shop on the San Augustine Plaza. Salamon, 29, was born in Dallas but was put up for adoption at birth and raised by an Eastern European couple who survived the Holocaust and settled in Laredo. Salamon knew that she was Jewish but until September 1988 didn’t know the names or whereabouts of her biological parents. Her black eyes and dark skin reflect her Sephardic Jewish heritage. She talks about her life in Catholic Laredo and her search for and reunion with her natural parents.

Growing up in Laredo, I had four or five friends who were Jewish and a lot of non-Jewish friends, but you knew who was Jewish and who wasn’t. All our parents tried to keep us together, especially my parents, since they were Holocaust victims. They always said, “You’re Jewish; don’t forget, never forget.” They talked about the Holocaust all the time, not in detail but reminding me to never forget what happened because it can happen again. My father told me about losing his family in Lithuania and going in hiding and being afraid for his life. I don’t think he went through any really ugly stuff, torture or anything. My mother may have, I’m not sure. She was in Auschwitz, but she never talked about it.

They escaped Russia together after the war, got fake visas, and went through all the countries to a refugee camp in Italy, then after about two years they came to Laredo. My father’s three brothers had gotten here before the war and were living in Nuevo Laredo. My father got in the fabric business, started out as a peddler going from door to door. He spoke Yiddish, Russian, and Lithuanian but no English or Spanish, but somehow he made it. Eventually he opened a store on Convent, that’s the main street here in Laredo. In time it became a pretty big business.

I found out when I was a little girl that I was adopted. But I never told anybody because I was very embarrassed about it. I didn’t know what it was. I didn’t know anybody else who was adopted so I didn’t ever tell anyone. When I was fourteen or fifteen I mentioned looking for my natural parents, but my mother and father didn’t want to talk about it. I think they felt threatened, like I might run away or something. Then about a year ago they told me, “Why don’t you go ahead and try looking for them?” They were getting pretty old, and I guess they felt like in case something happened to them they wanted me to have more family.

They told me the name of the hospital in Dallas where I was born. One of my aunts remembered that my father was a tailor and worked at Neiman Marcus and that they had other children, so I started with those little bits and pieces. I got a court order from a judge in Dallas to get my original birth certificate, and from that I got the name of my mother and father and where they were born. My father was born in Libya and my mother was from Tunisia, so both were from North Africa, what are called Sephardic Jews. I called Neiman Marcus, and all they would give me was the address, which I had already gotten from the birth certificate. I told them, “Please, I’ve got to have something else.” I told them why, but the lady said, “I’m sorry. We’re not allowed to give out information.” and I said, “Please, it’s been twenty-eight years—what’s the difference?” So they gave me a social security number, and with that I eventually got an address and phone number in Brooklyn.

It was September 1988 when I called them. It was really weird. I didn’t know what to do; there’s no rules on how to do that, how to pop into someone’s life. I said, “Is your name so and so?” and the man told me, “We’re not buying anything” and started to hang up. I didn’t know what to tell him, so I go, “Did you have a daughter in 1961 that you gave up for adoption?” And he got really quiet. And then I go, “I think you’re my father.” and he started crying, and I started crying.

I found out I have two sisters and three brothers, all living in the state of New York. We talked on the phone and sent pictures and all. Then we had a reunion. I took my two children. It felt—I don’t know—neat to look at all these people. I’ve never known anyone who was blood-related to me, except for my children. I tried to look for similarities. They looked a bit like me. Oh, and they’d say, “You look like this aunt and like that aunt.” But these people will never be my parents. I mean, biologically they are my parents, but I can’t call them Mom and Dad. I don’t know what to call them yet.

Being Jewish in Laredo wasn’t easy when I was growing up. I hope it’s easier for my kids. I had problems in school. Some of the priests still taught that Jews should be condemned for killing Jesus. People would say, “You killed Jesus,” and I’d say, ”No, I didn’t, I don’t know him.” And I’d come home crying, saying, “Mommy, they told me I killed somebody, and I didn’t kill anybody.” I think it’s a bit more open now, but there are still a lot of people who have never met a Jew and think you have horns or a tail. I hope my children won’t have to go through that.

Trey Henderson

Lumberman

Lufkin

George H. “Trey” Henderson III, 31, is vice president in charge of production at Angelina Hardwood, a company started forty years ago by his grandfather. A devoted family man, Henderson is also an avid volunteer who is taking over his father’s leadership role in the community. In his wood-paneled office, its shelves adorned with gimme caps, the six-foot-seven Henderson leans back in his leather chair, plops his feet on the edge of his desk, and talks about the family business and what it is like to be the boss’s son.

I started working when I was ten years old. We had a building we were clearing and I was throwing sticks in the fire and I came home for lunch the very first day with soot and ash all over my face, looking pitiful. My mother screamed when I walked in that back door. Here’s her first son—I’m one of three sons and two daughters—and here I am, the first one out there, and I had black soot from head to toe. It looked like I’d been in the coal mine for three days. She made me take my clothes off before I walked inside and told my daddy that if I ever came home looking like that again, she was going to pick us all up and move out. But I came home that afternoon looking the same way. He didn’t change a thing.

My first check was $54.50, I will never forget it. It was my mother’s birthday, and I bought her a purse. I was sick the day of her birthday. I couldn’t go to work and I knew the purse I wanted to get, but I couldn’t go buy it, so my dad took my money and bought the purse for me. I remember wrapping it in light blue paper, but we didn’t have any tape. Couldn’t find Scotch tape for nothing. So we got some Band-Aids out of my mom’s first-aid kit and we taped it with Band-Aids all along the outside and presented it to her like that. I was so proud of that I didn’t know what to do. There’s few things that ever meant more to me than that. When I look back, that had to be one of the ugliest purses. I don’t know if my mother ever carried that purse.

After that, I probably didn’t go back to work until I was fourteen or fifteen. I would work the summer shifts, but then I decided I would jump off and one summer I worked for a local veterinarian. Loved it. Thought that might be what I wanted to do. But it kept coming back that I enjoyed coming out here. I threw sticks in the fire, and then I would drive an old dump truck around and pick up sticks and things in the yard. You know, that wasn’t the way the boss’s son was supposed to work. I fell in there and worked and sweated and got dirty with the rest of them, and I paid what I felt like were my dues.

I worked four straight years in the summer, and each time I was able to move up a step. When I got out of college I was wanting to go to the plant to learn how to run it. They let me get involved in a management position that I definitely qualified for because of all my past work history. If somebody had come in there cold turkey, they probably couldn’t have done that, but I knew the terminology, I knew what to look for, I knew how to grade the wood, and I was able to tell that to the others. They respected my position because of my growing up through it. So while I really hated doing a lot of that dirty work at the time, I wouldn’t trade it now for anything.

I respected the fact that my dad did not force or pressure any of us into working out here, and so I’m going to do the same with my sons. If either one or both of them make the choice to come out here, sure, boy, I’d love it. If they would rather pursue something else, I’ve got no argument there either. My main thing is that they do what they want to do. I just hope they’re successful.

For now, they really enjoy coming out here, and of course, my dad loves to see them come out too. I can remember when my mom would bring me out, and I would run in and see my granddad. I just did it ’cause he wasn’t around that much, and I think he really enjoyed seeing us. We would walk in and sit down—my grandfather, my father, and now me, a leg propped up on that desk, that’s the way I remember it. There would be a stack of mail that high and he’d sit back and pop that mail open and we would just talk to him. He died back in ’75, but I remember those moments of being able to run out to the plant, visiting with him and seeing him at his job. We probably got in his way, but he never let it be known and he never ran us off.

Barbara Scoggins

Herb Farmer

Winnsboro

As a newly divorced mother of two searching for a livelihood, Scoggins fell into the booming real estate market of Dallas in the early seventies. Success came quickly, allowing the family to live in the toniest neighborhoods in town. Scoggins had always wanted to live in the country, and when her children left home, she was free to chase her dream. The bust made it that much easier to leave her real estate job, so she purchased a small farm a hundred miles east of Dallas. She has reaped the rewards of her long hours and hard work; her organic and pesticide-free herbs are in big demand in Dallas restaurants. Sipping tea in the living room of her house adjacent to the farm, Scoggins, 47, reflects on the benefits of a rural upbringing.

I grew up in the country; we lived out in Harlingen. I had a little plot of ground that was mine, and you could raise whatever you wanted to. Of course, down there you have all these Mexicans that plant for you. You point and they understand—“I’d like to have that over there.” So it all got done.

I know that when I went to St. Mary’s Hall in San Antonio the thing that struck me—and then again at SMU with all these city people—was that their vision of life was so narrow. My vision coming from a little bitty town was you can do anything, because you had to out on the farm. You had to kind of ad-lib. You found yourself being a more diverse person than I think you are when you grow up in the city.

It also struck me that all these kids I was going to school with were so structured and set. Their whole life was already mapped out, and it just seemed real confining to me and tunneled. Most of the people I met who grew up in the country, their visions were more horizontal, instead of vertical.

I like being back out in the country. Dallas has gotten to be such a different place than it was when I first moved there in the sixties. The people are real different—lots of Northerners, California people. They think differently than most of us do. Dallas is beginning to be a fast place. Loud place. Crowded place.

We always lived in the Park Cities, and so that was like a little town again. Our houses were some of the nicer ones on the block. And yet that wasn’t so good either, because my kids were so unprepared for other people’s lifestyles. I had rental property in some really raunchy areas of town, a real slum landlord, and I would take them over there to clean, paint, help fix up. I said, “We all appreciate the dividends off these places, so we’re all going to contribute.” But here again, that’s how I’ve been raised. All for one and one for all. My son really resented that. In fact, he went ahead and got a job where he got paid for his work—thank you very much.

They thank me now for having taken them around, because they would go, “Ooh, how could people live this way?” And that really upset me. I said that people are always on the move, you are either on your way up or you’re on your way down; people are always in flux, and it’s not their fault. When you’re on your way down, maybe you didn’t have the education, maybe you’re just in a string of bad luck. But this place that you all think is awful might be three steps up from the next renter’s last place. And you all may live in a place like this someday as an interim, and it is not because you don’t have education—it’s not because of anything except circumstances.

Now they can appreciate it. And I’m happy for them to know it. What you do is who you are. Where you live is no big deal.

Bishop Powell

Teacher

Abilene

Powell, 38, teaches eighth-grade English. In their middle-class home in a neighborhood right out of a Norman Rockwell painting, Powell and his two sons, nine and eleven, play a medley of contemporary pop tunes. Powell’s wife, Mary, listens, and their four-year-old daughter looks as if she wants to join in. Music is the sustaining passion in this family, as Powell explains.

Playing music is what I really like to do. My mother sang. My dad played the fiddle. My grandmother played piano. We all knew the same songs.

My grandmother played strictly by ear. When she was a little girl, she would play the piano for her Baptist church. And the song leader would get up and say, “Now we’re gonna do ‘When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder,’ and I want it to be right about here . . . hmmmm. ” And she would catch the tone and play in whatever key he hummed at the time.

I kind of learned that from her. I don’t know if you learn it by ear or what, but she taught me how to anticipate and play like that. And now I’m finding out that it is something a lot of folks can’t do—play in any key at the drop of a hat.

When I was growing up in Ballinger, the local people—even kids my age—would all sit out on the back porch at night and play. And it was not uncommon for a person to play two or three different instruments. I played the guitar, fiddle, banjo, keyboards—just anything with strings. Once you can play one, you can play two or three more. We played western and folk music —Bob Wills, western swing, some gospel stuff, blues. I love to play blues.

But when I got away from the community, all of a sudden I realized that this was not a real common thing. And you know, that’s something that really bothers me about our society today. There’s no place to play if you don’t play in bars and dance halls, unless you just do backyard picnics. People today send their kids off to music lessons, but the lessons don’t relate to anything because the families don’t play together.

Clyde Blackman

Museum Director

New Braunfels

Blackman, 66, is a former principal and administrator of experimental programs for the Houston Independent School District. A sardonic man with a quick wit and strong opinions, Blackman talks about his disillusionment with the school system, his decision to change professions, and how he became a mother at age 64.

In Houston we had principals and professional administrators who never did a thing but shuffle paper. About every five years a new superintendent would be appointed, and all the old administrators would run to the new superintendent and give him a few clichés from the current lexicon of catchwords, and he in turn would give them a new title. He would just rename fools at a higher level. And then as soon as they had been renamed, they would sit down and wait for the next superintendent.

When I was 56, I decided to try something completely different, and that’s when I went back to school and got my bachelor’s degree in accounting. Now remember, I had had a doctorate in bilingual education since 1968, but they made me take 68 hours to go from an education degree back to a B.S. in accounting.

My wife was a clinical psychologist in Houston at the time and was diagnosed with cancer, a kind of cancer that caused her bones to break quite easily. So Houston, being the way it is, very impersonal, she was frightened to get out of the house at all. So we built a house in New Braunfels, and I commuted back and forth for about five years, working as an accountant.

Finally, she got critical. I kept her a whole year in Houston in the townhouse with me and we kept the house in New Braunfels and then I decided to retire again and to nurse her. We moved back, and I nursed her until she died in 1986. During that time I became a docent—a volunteer—at the Sophienburg Museum, and when they asked me to become director, I was, of course, delighted.

I have one daughter who lives in San Antonio, and my wife wanted to be close to her without living in the same city. When I was nursing my wife, my daughter was pregnant and wanted to go back to Southwest Texas and get a master’s degree. And her mother said, “Well, Daddy’s home anyway, so why don’t you go ahead, and we’ll keep the baby and you’ll go to school every day.” Six weeks later my wife died. And I had the baby every day for two full years.

I got the baby at six every morning, and I got it bathed by six in the afternoon when the mother came. I cooked all of their food, so the baby didn’t know us apart. She called the mother Daddy and me Daddy and her daddy Daddy. She finally worked out that I was Pappaw and that daddy was Daddy, but she didn’t know what to call her mother because nobody called her mother Mother—her name is Blossom, and my granddaughter started calling her Boss, which we thought was great. So I was a mother for two years. It was an interesting experience. I knew exactly when it was Mother’s Day Out in our neighborhood.

- More About:

- TM Classics