This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

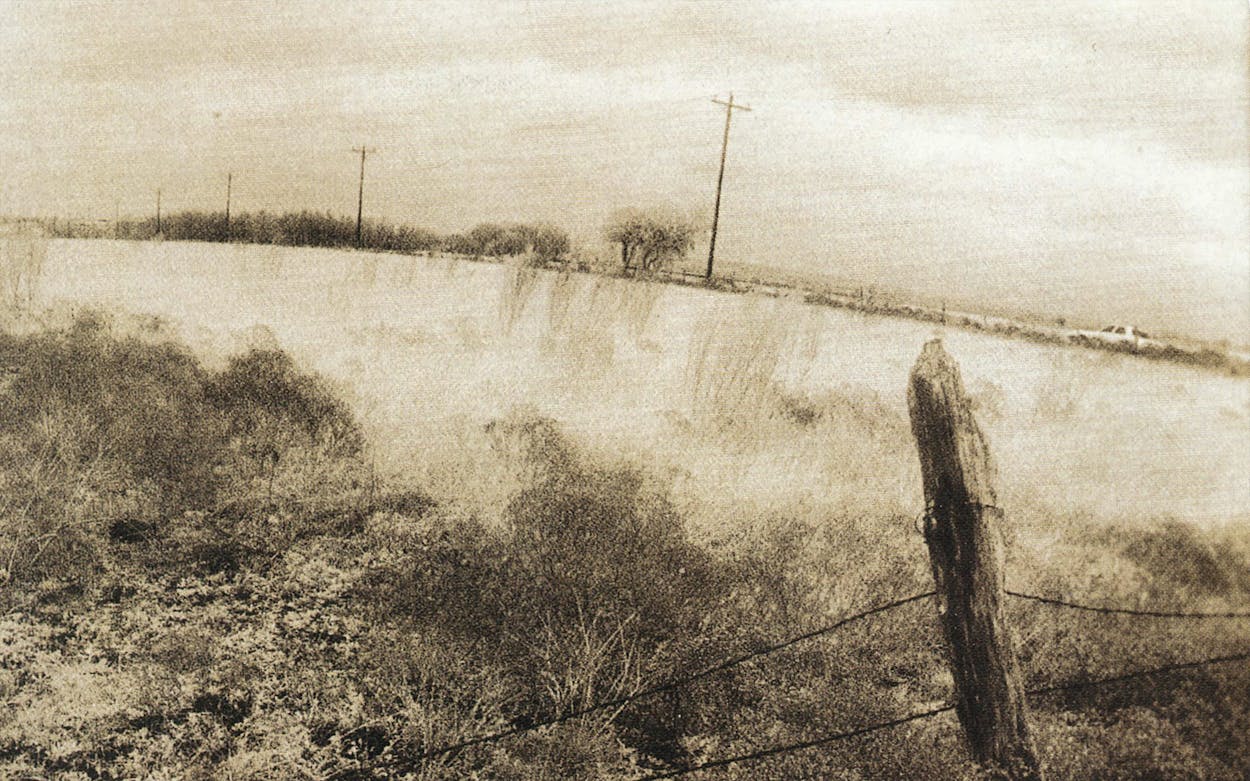

It had been raining hard for a week, and on this still overcast day the country beyond Loop 1604 was lush with suppressed light. Here, on the frontier of San Antonio’s suburban expansion, the land retained a suggestion of primeval Texas. Blazing swaths of wildflowers had taken over the brushy landscape, and in the creek bottoms the stout hardwoods were knitted together with tensile loops of vine.

The particular tree I was looking for, an aged live oak, stood by itself on the edge of the road in a field of white poppies. In the center of its trunk was the scar of an old wound, so smoothed and weathered by time that now it appeared only as a faint gray stain in the bark. Had I not been looking for it, I would not have recognized it for what it was, would not have seen that the wound was in the shape of a cross. Someone had carved the cross into this tree hundreds of years ago, probably a Franciscan priest accompanying one of the many Spanish expeditions that made their way through Texas up the Camino Real, the “Royal Road” or King’s Highway that ran from San Juan Bautista on the Rio Grande to the failing missions scattered west of the Sabine. At one time, along the various ragged trails that made up the Camino Real, there must have been many crosses like this one marking the way, signs to invoke the presence of God in the wilderness, tokens of thanksgiving for a safe river crossing or the passing of a furious storm. Today only a few are left, and where you find them you find the road.

In front of this tree I could make out an eroded vestige of the Camino Real, a shallow, meandering rift in the ground that looked no more imposing than a creek drainage. And yet this barely perceptible ditch was once the track upon which New Spain made its fitful, conquering advance into the wilderness beyond the Rio Grande. It was the basic route along which the history of Texas would be determined. Though many of the missions and presidios that the Spaniards established along the Camino Real rotted away in the jungle humidity of the East Texas forests, others took root and grew into cities like Nacogdoches and San Antonio. As early as Spanish Colonial times, the road served as a boundary to mark land grants. It was used by French smugglers and by Anglo-American filibusters. The Camino Real was the road that both Davy Crockett and Santa Anna—coming from different directions—traveled to reach the Alamo.

No one knows precisely how long the road has existed. Before it was a Spanish thoroughfare it was probably an Indian trail, and the Indian trail itself may have followed a route first defined by the hooves of migrating bison. According to the Texas Legislature, which enacted a Senate resolution last year to commemorate the road, the Camino Real will be three hundred years old in 1991. “The roadway,” reads the resolution, “was officially established under the authority of the first provincial governor of Texas under Spanish rule in 1691.”

Since history records no ribbon-cutting or other ceremony to mark the official inauguration of the Camino Real, however, the Legislature’s announcement of a 300th anniversary is a bit arbitrary. The provincial governor referred to in the resolution—a man named Terán de los Rios—did use the road in 1691 to travel into the interior of Texas, but the route of the Camino Real had already been laid out during the course of two previous expeditions led by Alonso de León.

Almost everything having to do with the Camino Real—its origins, its exact course, even its name—is hazy and half-defined. In the days when Texas was a part of Spain, “Camino Real” referred to an official highway, a road—however rough—that linked the king’s holdings and helped to further imperial policy. On the King’s Highway, you traveled under the king’s protection.

The Camino Real that crossed Texas is better known as the Old San Antonio Road, and that is how the Legislature refers to it in its anniversary resolution. As a name, the “Old San Antonio Road” is a holdover from the nineteenth century: When the Camino Real was first blazed in the late seventeenth century, San Antonio did not yet exist. The original orientation of the road was toward the east, from the Rio Grande to the Sabine, and on into Louisiana. Later, as the Spanish hold on Texas grew shaky, settlers and provocateurs from the United States streamed down the road from the opposite direction.

Finding exactly where the road ran—from either direction—is a complicated business. Though traces of the Camino Real are still visible here and there, for much of its length the road is a ghost, grown over or paved under, disappearing between the established reference points. Its presence can only be inferred. In 1915 the Texas Legislature hired a civil engineer named V. N. Zivley to locate the road and mark it. Zivley threw himself into the task with antique patriotic fervor. “This is the road,” he wrote, “over and by which most of those ‘mighty men of valor’ who afterwards founded and established the Republic of Texas, unfurling the Lone Star Flag to the balmy Southern breezes, entered the land of their choice.”

Zivley had no great trouble locating the basic route of the “Anglo” section of the Camino Real, the part that ran from east to west. The route Zivley marked follows the course of Texas Highway 21, through San Augustine, Nacogdoches, Alto, Crockett, and Bastrop and into San Antonio—“the City of the Alamo,” the engineer noted, “that altar consecrated by Anglo-Saxon blood to the God of Liberty.”

South of San Antonio, Zivley found the road considerably more difficult to trace. The physical evidence was faint and spotty, and about the only thing Zivley could find to document the course of the road was a diary kept by a priest named Juan Agustín Morfi in 1778 (“To that old padre,” a relieved Zivley wrote, “though I am a protestant of the most ultra blue stocking type, I want to doff my hat”).

Zivley’s reckoning of the route was accurate enough for its time, taking into account his obvious bias toward that part of the road upon which Anglo-Saxon feet had trod. A few years after his survey, the Daughters of the American Revolution commemorated the route he designated by erecting hundreds of pink-granite markers, one every five miles. The markers were scrupulously placed along the actual route that Zivley marked, but since in many instances this was an out-of-the-way spot, citizens dug them up and moved them to more prominent locations like courthouse lawns or highway rest stops (in some counties, every single marker has been displaced). And over the decades, as more and more archival records from the Spanish Colonial period have come to light, Zivley’s confident accounting of the road’s course has become less and less definitive.

For the 300th anniversary of the Camino Real, the Legislature directed the State Department of Highways and Public Transportation to, in essence, find the road again. The highway department and the Texas Historical Commission were to present a historic preservation plan to the state Legislature. They had a year to do this and a staff of five. When I dropped in at their Austin office one day in April, they were about halfway through.

“It’s a booger,” Al McGraw, the staff archaeologist and project director, told me. He was smoking a pipe in a windowless storage room, whose long rows of shelves held various archaeological artifacts. In other rooms the staff was poring over photocopies of old land grants, deeds, historic maps, and survey reports. One entire wall was covered with a chart that broke down the details of each of the Spanish expedition diaries: date, starting and ending locations, leagues traveled (a Spanish league is 2.6 miles), direction, and comments (“passed the point of a little hill where oak clump ends at 1/2 league from camp”; “crossed 2 creeks; pecan and oak woods for 5 leagues”). Out of such puzzle pieces a coherent picture of the road was slowly emerging.

But the clearer the data, the more fragmentary and various the Camino Real became. The essential road of Texas history, McGraw and his staff were discovering, was not, strictly speaking, one road at all. “What you have to realize,” McGraw said, pointing to a Texas map that had a series of interwoven lines drawn on it in different colored markers, “is that the Camino Real—the old San Antonio Road, whatever you want to call it—was not just a single trail. It was a network.”

The lines on the map reminded me of an erratic riverbed, constantly meandering and shifting, a series of braided channels that ultimately led to the same destination. Each variant of the road had its own name: the Upper Presidio Road, the Lower Presidio Road, the Camino Pita, Camino de los Tejas, the Camino Arriba. The reason for this web of routes is easy to understand. In its early existence the road was a faint track, hardly more than a suggestion. Almost every expedition that used it found a way to improve upon it. Over time the travelers discovered more-efficient river crossings or routes that would help them skirt natural obstacles such as El Atascosa, the boggy alluvial plain south of San Antonio, or the dense forest—El Monte—near present-day Bastrop, under whose gloomy canopy the Spanish soldiers tended to grow anxious and disoriented. It is believed that when the Apaches, pressured by the Comanches to the north, began to raid below the Hill Country, the road looped south into the less hospitable brushland to avoid them.

But all the routes began in the same place, at a frontier outpost known as San Juan Bautista that sat in a pecan glade on the south bank of the Rio Grande. At the time the Camino Real was created, San Juan Bautista was nothing more than a remote settlement built around a mission and the presidio that guarded it. Over time, however, it became a major staging area for the royal expeditions that filtered up from the interior of Mexico, headed for the unknown lands of Texas.

The town that grew up around San Juan Bautista is called Guererro, and it is enthrallingly old. I drove there one day in late spring, crossing the border at Eagle Pass, driving through Piedras Negras, and heading about thirty miles east into the Mexican state of Coahuila. In midafternoon, the streets and square of Guererro were empty, and the town had the echoing stillness of a stopped clock. There were no sounds except those that might have been heard here three hundred years ago—the creaky calls of Chihuahuan ravens, the crowing of roosters, the noise of the wind rushing through the pecan leaves overhead.

The parade ground of the old presidio had become the town square, and many of the ancient buildings from Spanish Colonial times—the presidio captain’s house, the paymaster’s house—were not only still standing but still in use. Some of the houses now had modern stucco fronts, but along their sides I could see the bare walls of stacked stone, the mortar long since eroded away.

Other structures were vacant and half fallen in. I chose one and walked inside. Most of the roof had collapsed, and the floor was a weedy mass of rubble and broken bottles. The house had been unused for so long that a large tree had grown inside of it, though in an adjoining room the old roof beams were still in place, supporting a few remaining scraps of brittle sod overgrown with prickly pear.

Emerging through a low doorway, I stood for a moment in the sun and gazed across the square, at the former plaza de armas of the presidio. The occupants of this house might have stood in this same spot, watching the various entradas assemble and march off in high spirits toward the Rio Grande, the first of the many rivers they would cross in their journey through what is now the state of Texas.

Those early expeditions crossed the Rio Grande at a place several miles distant called Paso Francia—“Frenchman’s Crossing.” It was called that for a reason. Near the end of the seventeenth century, Spain’s claim that it possessed the land beyond the Rio Grande was not much more than rhetoric. In fact, the march of Spanish civilization had just about stalled out in the deserts of northern Mexico. Texas was a looming wilderness at the farthest margin of Spain’s farthest frontier. There was no compelling reason to venture into it, and hence no need for a royal road.

But the Spaniards were roused to action when they heard rumors that the French had invaded Texas from the Gulf of Mexico and had planted a colony somewhere on the coast. These rumors were given alarming credence in 1688, when Alonso de León, the governor of Coahuila, happened upon a Frenchman living in an Indian village about sixty miles north of the Rio Grande, west of present-day Uvalde. The man was about fifty years old and crazy, but he had managed to entice the Indians into treating him like a potentate. De León found him sitting on a cushion made of buffalo hide while members of his court cooled him with feather fans. He was surrounded by a bodyguard of forty warriors.

When he saw his visitors, he jumped from the cushion, pumped their hands in greeting, kissed the priest’s scapular, and happily announced in his fractured Spanish, “¡Yo francés!” (“I French!”).

“I am going about assembling many Indian nations,” he told De León, “to make them my friends; those who do not wish to join me, I attack and destroy with the aid of my Indian followers.”

Exactly who he was, what he was up to, and where he had come from nobody ever really knew—least of all the befuddled Frenchman himself. But something he told De León helped change the course of history. He said that a French settlement—with a fort and a township—had been established on the banks of a “large river to the east and had been there for fifteen years.”

There was indeed a French fort. De León spent the next year looking for it and in the process opened up the route of the Camino Real. But instead of a formidable French presence, he found only a ruined and looted stockade, the ground strewn with pig carcasses, rotting books in leather bindings, and a woman’s skeleton still wearing the tattered scraps of a dress. That was all that was left of Fort St. Louis, the colony that the French explorer Sieur de la Salle had attempted to establish on Matagorda Bay. La Salle himself had been killed by his own men, and the rest of the desperate colonists had been overrun by Karankawas.

The French threat seemed to have taken care of itself, but because of it the Spanish road into Texas had been opened, and De León’s next discovery helped guarantee that it would remain so. Traveling north and east, pursuing rumors of French survivors, he entered the country of the Hasinai, a confederation of tribes whose name, in all its variations—Tayshas, Taychas, Tehas, Teias, Texia, Teisa, Teyans, Teyens, Tejas—meant “friend.” De León found the “kingdom of the Texas,” and it indeed seemed to be a land of friendship and welcome. These Caddoan people were settled and affluent—skilled farmers who kept their surplus maize and beans in watertight cribs inside their huge conical houses. To the Spaniard’s astonishment, they had even been visited by the Woman in Blue.

The Woman in Blue was a weird spiritual phenomenon of seventeenth-century Spain. In physical reality, she was a Castilian abbess named Mother María de Jesús de Agreda. María de Agreda never left her convent in Spain—but she became famous for her claims that she was able to transport herself to faraway Texas. There she appeared before the Indians as a beautiful woman in a blue cloak, bewitching them into Christian belief.

So far, the Woman in Blue had shown herself only to the Indians living along the Rio Grande, but now here was evidence that her spirit was roving deep into the unknown lands to the east. It is reported that the Hasinai chief who De León encountered even had a portable altar, complete with figures of Christ and the saints, in front of which a light was kept burning in perpetual veneration. The chief told Father Damian Massanet, the priest accompanying De León, that he would welcome further spiritual instruction.

So all at once New Spain had compelling business in distant Texas. It would establish presidios to guard its borders against the French and missions to turn the Indians into servants of God and Spain. To do all this, it would need a road.

The road came into being slowly, league by league, river crossing by river crossing. It was never actually “built” but simply improved upon, its route modified by almost every expedition that used it. To call it a road at all is misleading. The Camino Real was not nearly as imposing, for instance, as the broad curbed highways the Anasazi Indians had built hundreds of years before, far to the west in the New Mexican desert. The Spanish road was a track, rarely wider than a single oxcart, and often so indecipherable that the professional explorers who followed it routinely got lost.

When I left Guererro, traveling northeast toward San Antonio, I was following the general trend of the Camino Real, but there was hardly any physical evidence to mark the actual route of the old road. I crossed the Nueces, the Hondo, the Medina, glancing down at the rivers from the highway bridges as I sped across, thinking of the Spanish horses churning madly in the water, and the soldiers and Indians ferrying sheep across one at a time.

The crossings were routinely hazardous. On Domingo Ramón’s 1716 expedition, 82 horses were drowned trying to reach the far bank of the Medina. Ramón, sensing the devil’s hand in this calamity, ordered a mass the next day “to crush him.” Don Domingo de Terán, starting out on the first expedition to establish the missions in East Texas, lost 49 saddle horses to the Rio Grande. “However, the great power of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the North Star and protector of this undertaking, carried our weak efforts in this task to a successful ending.”

Day by day these entradas had staggered down the rude path of the Camino Real—the soldiers outfitted in buckskin or quilted cotton, plodding along under the weight of their harquebuses and leather shields; the friars and lay brothers in their brown robes, a few of them heroically barefoot, the rest with their gnarled and swollen feet encased in sandals; the mission Indians driving herds of goats and sheep; the oxcarts packed with trading goods and religious implements, including holy-water fonts and ovens for baking communion wafers; and the banners overhead, bearing the images of Our Lady of Pilar or Our Lady of Guadalupe or St. James the Moor-Killer.

When I reached San Antonio, I traveled along Mission Road, more or less following the course of the old road as it passed icehouses and auto-repair shops and Pig Stands, almost incidentally passing the missions of San Juan Capistrano, San Francisco de la Espada, San José, and de la Purisima Concepción. These missions were begun by the Spaniards early in the eighteenth century, after those in East Texas had been abandoned and the padres were ordered to retrench along the San Antonio River, where the local Indians proved to be ultimately more agreeable than the Hasinai.

Domingo Ramón’s expedition of 1716 had been the first to describe San Antonio Springs, the glorious headwaters of the San Antonio River. It was near there, two years later, that the village of San Antonio de Béxar was founded. The first mission to be built in the town—San Antonio de Valero—was moved twice, allowed to fall into ruin, and finally secularized in 1793. For a time it served as the headquarters for a Spanish cavalry unit, most of whose members came from a town in Mexico named Alamo de las Parras.

I parked my car in a lot by the San Antonio River and walked through the lobby of the Hyatt Hotel to Alamo Plaza. Standing in front of the chapel, I reckoned that the Camino Real would have passed a few hundred yards to the east, and I tried to imagine Santa Anna’s forces wheeling into position for the siege. Striking out in 1836 from Mexico to suppress the rebellion in Texas, Santa Anna had driven his army up the road in a cold-blooded forced march that left many of them buried along the way, his bewildered conscripts from the tropical jungles of the Yucatán dropping from exposure in a freak blizzard.

And this is where the Camino Real had led him. The Battle of the Alamo was no accident. By 1836 Anglo-American immigrants had for several decades been on a collision course with the Spanish and Mexican governments that held Texas, and now the two cultures hurtled toward each other from opposite ends of the Camino Real like locomotives on a single track. The wreck had to occur someplace, and that someplace—sitting smack in the middle of the road—was the Alamo.

Leaving San Antonio, I took Interstate 35 north, which kept me roughly parallel to the route of the old Camino. Near San Marcos, I met up with Stephen L. Hardin, a historian working for the highway department on the Old San Antonio Road project. Tall and bearded, Hardin wore a cap featuring the logo of the Sons of the Republic of Texas and a belt buckle emblazoned with the state seal. For the last four months, he and fellow researchers had been reading and annotating old diaries, searching for maps and land records, interviewing farmers and ranchers, and driving from one end of Texas to the other, trying to uncover archival or physical clues that would pinpoint the road.

“John Ford movies to the contrary,” he told me as we drove along in his beat-up Subaru, “a bunch of guys just can’t head off across the prairie. You’ve got to have a road. And it’s axiomatic that roads follow roads, that new paths follow old paths when they’re able to. For instance, I-35—from about York Creek south to San Antonio—is the lower Camino. This road we’re on now”—we were driving on a dirt road off U.S. 183, the Lockhart Highway—“follows the original route of the later Camino Real. And I think it made an arc down here and linked up with Highway 21. If you’d been a volunteer coming down from Louisiana to light in the Texas Revolution, this is the road you would have taken to the Alamo.

”Now, I’ve been told,” Hardin said, stopping the car a few miles east of San Marcos, near the intersection of Highway 80 and Highway 21, “that you can see swales of the Camino Real on this golf course.”

He got out to look, squinting and studying the contours of the fairways as golfers teed off under the trees, but he could find no marks of the old road. A few miles farther south, though, on the Old Bastrop Road, he pulled over and pointed to a deep ditch on the other side of the barbed-wire fence.

“In terms of physical evidence,” Hardin said, climbing onto the fragile roof of the Subaru for a better view, “this is one of the best places in Texas to see the road.”

It looked nothing like a road, of course. One of the unexpected peculiarities of the Camino Real is that it is preserved not just in shallow ruts but in pronounced gullies, because centuries of rain have channeled water into the original roadbed and scoured it deeper. The gully here was grown over with bluebonnets. It ran straight for several hundred yards and then, near the crest of a shallow hill, curved and closed up like a seam.

We spent the rest of the afternoon in San Marcos, where Hardin pondered the question of exactly where Domingo Ramón’s expedition would have crossed the river in 1716. Hardin had established that the Camino Real came in from the west, following the course of present-day Hopkins Street, but he doubted that Ramón had crossed the river where the Hopkins Street bridge now stood. The water was too deep there, the bottom too sandy, the banks too steep.

“Espinosa provides the best clue,” Hardin said. (Espinosa was a priest and diarist of the Ramón expedition.) “He says that they crossed the San Marcos two harquebus shots from the headwaters. A harquebus shot is not usually more than a hundred yards.”

That brought us to the Sewell Park bridge, just below the tourist attraction of Aquarena Springs. Here the banks of the river were lower, and through the clear shallow water we could see the gravelly bottom.

“This is all becoming clear to me,” Hardin said, growing excited. “They probably came in on Hopkins Street, found it a bad place to cross, then followed the bank upstream a little ways.

”It’s obvious,” he said, pounding the steering wheel with his fist as we drove past the entrance to Aquarena Springs. Above us, on the left, the Balcones Escarpment rose in stark perspective. “It’s obvious what they did! After they crossed the river they would have followed the hills! It becomes clear now. It becomes clear! This is the perfect place for a road. You know, sometimes it just bites you on the butt!”

After I parted company with Hardin, I drove east, through Bastrop, following the ghostly route of the Camino Real as best I could along Highway 21 as it led from the edge of the Hill Country to pastoral prairies and logged-over forests replaced with a roadside veneer of pines. This was the section of the road over which Zivley’s “mighty men of valor” had come tromping into Texas, and the success of this Anglo-Saxon thoroughfare was memorialized in the very asphalt under my tires. That this was the Old San Antonio Road was proudly proclaimed by highway signs and by the pink-granite markers of 1918 along the roadside. In Crockett, at the bottom of a railroad overpass next to a gas station, I noticed a billboard-size sign proclaiming “The David Crockett Spring.” The sign depicted Crockett drinking from a burbling pool as deer, rabbits, and armadillos respectfully looked on. “The David Crockett Spring,” the sign read, “which marks the camp site of the famous Texan [never mind that he was a Tennessean!] on his historic journey to the Alamo where he paid the supreme price for Texas Liberty.”

Farther down the road, outside of Alto, I stopped at the roadside grave of Helena Kimbell Dill Nelson—“Mother of child thought to have been first Anglo-American born in Texas, in 1804.” The vault had been reinterred in concrete, and the lettering on the tablet was so eroded that it looked as if it had been carved in salt instead of marble. But the fact that this simple grave had become a monument only emphasized the central irony of the Camino Real. The road that the Spanish had originally blazed to ensure that no foreigners could penetrate their borders had in the end become an avenue of conquest.

Highway 21 led into Nacogdoches, where it became a red-brick street running through the center of town. Main Street had, indisputably, grown up on the exact course of the Camino Real. There was no need to look for river crossings or swales to infer the presence of the road. This was it, still in use, still the main street of this ancient city. Nacogdoches began as a Hasinai village, and just a block from downtown I located a stunted burial mound, covered with grass, standing by the curb in somebody’s front yard with such matter-of-factness that my initial reaction was to wonder how difficult it was to mow.

Nacogdoches’ strategic location exposed it over the years to every wind that swept down the Camino Real—from those first Spanish expeditions to roust the French and establish missions to the half-dozen attempts by Anglo-Americans to pry Texas away from Spain and Mexico.

Adolphus Sterne, a Nacogdoches merchant, was one of the principal financiers of the definitive Anglo uprising, the Texas Revolution of 1836. When sentiment against Mexican authority was at its highest, Sterne traveled to New Orleans and raised a company of volunteers he called the New Orleans Greys. Sterne outfitted the Greys with surplus muskets and uniforms he had found in an armory building on Magazine Street—gray fatigue jackets, white belts, wooden canteens, and absurd-looking U.S. Army forage caps made out of sealskin.

The Greys were doomed. Few of them would survive the revolution. But they came marching into Texas on the Camino Real in fine spirits, toasted as heroes and saviors by the settlers along the way. Among them was a German youth named Herman Ehrenberg, who later recalled the banquet that Adolphus Sterne gave the Greys in a field in front of his house.

Adolphus Sterne’s house still stands in Nacogdoches, just a few yards off the Camino Real. And in front of it is the field where that long-ago fandango was held. The main course at dinner, Ehrenberg remembered vividly, was a roasted bear named Mr. Petz.

“This huge creature,” Ehrenberg wrote, “was so skillfully dressed in his fur that he seemed to be still alive; his mouth was drawn back in a fierce grin and showed sharp, white teeth tightly holding the true colors of the 1824 constitution. Raccoons, opossums, squirrels, and turkeys surrounded Mr. Petz, while two large legs of mutton, roasted to a nice brown, and a substantial joint of beef completed the decoration of our board.”

From Nacogdoches most of the Greys went on to fight and die at the Alamo or be executed at Goliad. Herman Ehrenberg was one of only a handful of men to survive the Goliad massacre. Reeling from a sword wound to the head, blinded by gunpowder, he jumped into the river shouting—he would have us believe—“The Republic of Texas forever!” and managed, after many other adventures, to find his way back to the Texas army. After that he went home to Germany and wrote his memoirs to pay his way through college.

From Nacogdoches I headed east, stopping in San Augustine at the site of Mission Nuestra Señora Dolores de los Ais, founded by Father Antonio Margil de Jesús in 1716. Fray Margil was the most venerated character ever to set foot on the Camino Real—a restless, dauntless, almost pathologically holy man who slept three hours a night, hardly ever ate, and was so humble he signed all his correspondence La Misma Nada, “The Same as Nothing.”

Margil was born in Valencia, Spain. His favorite activity as a child was building miniature altars, and when he began studying for the priesthood, he mortified his flesh with such enthusiasm that the Master of Novices, alarmed, took away his hair shirt.

Arriving as a missionary in the New World, he threw away his sandals and impressed the Indians by sometimes wearing a crown of thorns and trudging around under the weight of a heavy cross. He wandered barefoot through all the wild lands of Central America, establishing missions and apostolic colleges and narrowly escaping, time and again, the martyrdom he craved. He became so famous that sometimes when he approached a village he would find an arch erected in his honor and hundreds of people waiting to strew flowers in his path. This of course horrified him. He wanted only the ecstasy of oblivion. On his deathbed, he maintained that he did not even deserve a Christian burial, that he should instead be tossed “out in the wilds, where the beasts can devour me.” The priest who heard his last, brief confession was of the opinion that he had never lost his “baptismal innocence.”

But not even Margil could make the East Texas missions a successful enterprise. They were a disaster almost from the beginning. The Hasinai might have been originally entranced by this exotic new religion, but they were such accomplished farmers that the idea of abandoning their fields to plant mission crops made no sense. In some areas, smallpox killed half the Hasinai population. The priests mobilized to baptise the dying, but as the Indians watched the holy men pour water over the victims’ heads, they concluded that the act of baptism itself was lethal. Nor did they care for the lamb broth that the priests fed the sick. They called it “dirty water.”

Mission Dolores de los Ais was abandoned in 1719, its wooden church and buildings slowly disintegrating in the humid air. Now there is nothing left of it, except for a few pottery shards and ancient postholes found by archaeologists and the historical marker sitting on an overgrown bluff above a stream terrace.

At Milam, on the Texas side of the Sabine, I turned off to call on Earl and Ingrid Morris. Earl is a local building contractor whose ancestor, Shadrack Morris, founded Sabine Town, a once-thriving settlement along the river. His wife, Ingrid, had been appointed by the governor to serve on the Preservation Commission. One of her areas of concern was how to commemorate the road once its route had been established.

The Morrises had offered to show me a cabin built in 1819 or so by James Gaines, who operated the ferry on the Sabine that the New Orleans Greys had used to cross into Texas. “At one time there were two thousand people here,” Ingrid said as we drove through the highway junction of Milam. “They even had a permanent gallows.”

She pointed to what looked like a bar ditch near the side of the road. “See that groove behind that old truck? That’s the Camino Real. It passed right behind that tree line, into the old town square.” “This particular place here,” Earl said, when we had traveled a few miles farther, “the road probably went around. It may not be real boggy around here, but there are sloughs all in it. Not really swamps, but pin-oak ponds and baygalls. Back then you would have wanted to go above your boggy places. If you’ve got a wide cart with big round wheels and an ox pulling it, you might make it through the donkey grass, but if you’ve got a narrow-wheeled wagon loaded down with pianos, it’s a different story.”

The cabin stood in a forested subdivision, set off by itself on its original site near a hollow sweet gum tree that Earl said was the home of a family of bobcats.

The cabin was grander and stouter than I had expected, a one-and-a-half-story structure with dogtrots on both floors, made of sturdy logs of square-notched longleaf pine. Light shone through the gaps between the logs where the batting had been removed for restoration, but the house was solid.

“It’s a very well-trimmed-out house for the time,” Earl said as we stepped inside. “And the floor’s all hand-planed.” He squatted down and rubbed his palm across the floorboards. “Whoever planed this was very good. It’s so discreet. You can’t feel the grain.”

It was a haunting place, haunting in its solidity, in the way it made the world of the Camino Real so suddenly vivid and timeless. Upstairs, on one of the walls, was a reminder about a steamboat departure—“the Buffalo will leave Hamilton for the pass Thursday at 4”—written in chalk 150 years ago.

When we left the cabin we strolled into the woods that fringed the clearing, leaving the bright sunlight for the deep brambly shade. When we had walked only a few yards, Earl turned to me and announced, “We’re standing right on it.”

We were in a narrow groove half filled with leaves: the Camino Real. To the left the groove continued toward the river and the now-submerged site of Gaines’s ferry. Beyond that was Louisiana. If it had been three hundred years ago, I could have turned to my right and started walking, keeping a sharp eye out for the trail, and ended up a few months later in San Juan Bautista.

But it would be impossible to follow the road now, and no point to it unless you were one of those people who feel complete only when face to face with the vestiges and traces of a vanished world they can never know. As we stood there in the roadbed, odd little bits of lore from those Camino Real diaries kept floating into my mind: the mules neglecting the coarse pasturage along the road to eat the moss off the trees; the sudden windstorm that picked up a horse and rider and deposited them several yards away; the small boy who wandered away from camp and was never found; the Hasinai priest who had put out his own eyes in order to enhance his spiritual sight.

Parts of the old Camino Real—like Highway 21—are still in business, but the days when it was the great Texas road are long gone. After Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836, the Camino Real quickly began to lose its significance. The new republic looked east to the United States, not south to its old enemy. There was no great need for a road to the Rio Grande when goods were streaming in from St. Louis and New Orleans. In this new Texas, the Camino Real led nowhere. By 1850, ranchers were asking for—and receiving—permission to string fences across it.

Yet here it was, still etched in this trough of soft dirt—a bygone route of imperial conquest, where people once walked under the official protection of the King of Spain. Near where we stood I noticed a collapsed earthen bank, littered with rotten lumber and overgrown with vines.

“You know what that is?” Earl asked. “Back in the early sixties somebody scooped some dirt out of the road here and built himself an atomic-bomb shelter.”

He smiled and kicked gently at the dirt with his feet. “You see,” he said, “there’s uses for the old Camino Real yet.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio

- Nacogdoches