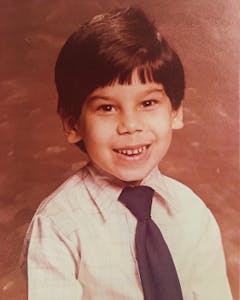

I can’t say my own name without stuttering. It’s perhaps the most common and cruelest joke played on the nearly 300,000 Texans—about 1 percent of the population—who live with this speech impediment, in which blocked speech patterns prevent fluid vocalization. Imagine being the new kid in class, being asked to stand up, share your name and a bit of personal information, and then enduring the mocking laughter that follows. That was a frequent (and miserable) experience for me when I was a student.

To me, stuttering feels like a dragon’s claw slowly squeezing my throat and chest. My ribs ripple under the pressure. My lungs squeeze against one another. The scales covering the monster’s skin pinch the skin of my neck and chin. I feel anxious just thinking about it.

Last week, however, I felt something else: pride. As the Austin American-Statesman reported, the University of Texas has received a $20 million grant to create the world’s largest center for stuttering research and education. Unlike most treatment centers, which focus on trying to “fix” someone’s stutter, the approach pioneered by UT professor Courtney Byrd emphasizes quality of life, confidence, and self-compassion. The photo accompanying the story shows a group of elementary school kids lined up at a microphone, waiting for their turns to speak, as part of a summer camp run by the university. As I looked at the image, I felt proud of those brave kids, and more than a little nervous on their behalf. It takes guts to stand up in front of a crowd, however small, and speak with a stutter.

After being overlooked and underfunded for years, stuttering is having a moment. In addition to the UT grant—which comes from Home Depot cofounder Arthur Blank, a stutterer—Joe Biden’s presidential campaign has brought new attention to the topic. Biden has called his stutter the “best thing that ever happened to me,” telling an Atlantic reporter, “Stuttering gave me an insight I don’t think I ever would have had into other people’s pain.” This summer, Brayden Harrington, a thirteen-year-old who stutters, gave a star speech at the Democratic National Convention. There’s a recent documentary, My Beautiful Stutter—Houston Astros outfielder George Springer, who has a stutter, is a coproducer—and a slew of new reporting on the subject, such as the New York Times’s recent piece on how remote learning can be harder for kids who stutter.

A common myth holds that people stutter because they are anxious or shy. It’s the other way around—stuttering can make an otherwise confident and outgoing person feel nervous about speaking. Stuttering is a neurological, genetically influenced condition, and for reasons that researchers don’t yet understand, it’s four times more prevalent in men than women.

I’ve never let my stutter stop me from expressing myself, and I’ve never been shy. My first-grade teacher, Ms. Gross, a tall, thin woman with the feathered hairdo popular in the early eighties, spent a lot of class time telling my best friend, Alvin Gonzalez, and me to stop talking. She’d try separating us, but by the time class was over, Alvin and I would once again be sitting side by side, chatting about Star Wars or whatever struck our six-year-old curiosities. This happened because halfway through class, I was escorted to a speech therapy session that was meant to cure or at the very least help me manage my stutter. Things went well during my thirty minutes with the public-school speech pathologist. Then I’d dart back to school and into a seat next to my amigo. Whatever advances I made during therapy quickly disappeared, and our conversation was punctuated by my stuttering and the uncontrollable volume of speech that accompanied it. Neither Ms. Gross nor Alvin ever mentioned my stutter, at least not that I can recall. Plenty of other people did. They still do.

My journalism career requires me to have countless conversations for stories. As Texas Monthly’s taco editor, I conduct interviews in a tangle of verbal spurts in English and Spanish and accompanying head movements. If the interview is conducted over the phone, the other person might think there is a problem with the connection. There rarely is. Sometimes adults (never taqueros) nervously laugh when I introduce myself. More than once, someone thought they were being clever by asking if I’m sure my name really is José. They might, like one radio station producer, freak out during a live recording and escort me out of the building by my elbow. Incidents like this have not prevented me from striving for personal and professional goals, appearing on other radio shows and podcasts, and being interviewed on live TV. It’s never stopped me from giving presentations at symposia, leading a taco tour, or ordering tacos, and it certainly has not stopped me from promoting my book. Promoting a book requires a lot of talking. In my case, it requires a lot of stuttering too.

Thankfully, writing a book and being a journalist has given me a platform to advocate for stutterers. Perhaps one of my tweets on International Stuttering Awareness Day will empower an individual on the social media platform. Perhaps my presence at a Zoom meeting of my local National Stuttering Association chapter will help another attendee.

Maybe one of the tots in the image above the Statesman article will decide to go into writing and dive headlong into all it requires. Maybe they’ll benefit from the research that comes out of the new UT center. And even if they don’t, I hope they never stop talking. I hope they never stop saying their name.

- More About:

- Austin