I was six years old the first time I heard about my grandfather’s encounter with the devil. The two met in 1945 near Anáhuac, Nuevo León, Mexico, about an hour southwest of Laredo. My grandpa was sixteen, playing poker with his cousin at a small bar out in the country, when a handsome, well-dressed stranger strolled into the room. He was tall and thin, sporting a crisp white shirt, black pants, and matching black boots. Immediately, for reasons my grandpa never fully understood, he suspected that this man was Satan.

He kept a cool head as the man approached and asked if he could play a hand. Cards were dealt, bets were made, and the tension grew as it became clear that the two were closely matched. When each revealed his hand, the stranger had won. But something felt off. My grandpa suspected that the man had cheated, and as their eyes met, the stranger’s smirk twisted into a terrible grimace. Two horns began sprouting from his forehead, and as Grandpa looked down at the stranger’s feet, he saw a chicken foot and a goat hoof in place of the boots.

Suddenly, the devil rushed out of the room, daring my grandpa to chase him. Grandpa didn’t hesitate—he mounted the horse he had tied up outside and tore off through the woods and brush. But no matter how fast he rode, he couldn’t catch up.

The next morning, he woke up in his bed, convinced it was all a dream. But when he went outside to check on his horse, the animal bore scratches from branches and brambles. Retracing the horse’s hoofprints, Grandpa discovered a separate set of tracks in the woods—made by a chicken foot and a goat hoof.

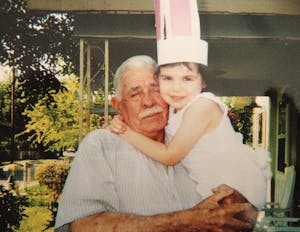

As a nosy little kid who wanted to grow up and be a writer, I spent much of my childhood visiting a little green house on San Antonio’s West Side, collecting stories from my grandpa Carlos Peña. His legend had already reached mythic proportions by the time I came along, in 1996. In fact, it had become a family tradition to traumatize little kids with the story of the night he met the devil.

Grandpa Carlos, who had bright white hair and a matching mustache, was a quintessential Mexican cowboy who, at six feet tall, towered over me. I called him Grampito, a portmanteau of “Grandpa” and “Abuelito” that came easily in a house full of Spanglish. He was almost never without a baseball cap or a cowboy hat, and in his later years—once my grandma wasn’t around to police his fashion—he was the king of camouflage, often dressing up in a full camo outfit with clashing patterns.

Under a pecan tree in his front yard or at the foot of the green recliner in the living room, I listened to tales from his life as a zookeeper, a lion tamer, and a migrant farmer.

For the most part, the stories were true. For example, he loved to relate how my grandma Josefina was tricked into marrying him. They met at a dance in Anáhuac in their early twenties when she stole him away from another woman, thinking he was rich because he was from out of town and dressed in nice clothes. After they got married, she found herself in a one-room house on his family’s small ranch, which they called “La Escuadra,” shooting rabbits and cooking them for dinner.

Neither of them came from much. Grandma was raised by a single mother in Lampazos de Naranjo, Nuevo León, who cleaned and cooked for her neighbors to provide for her three children. Grandpa had to drop out of elementary school in Camarón to help support his family. For a while, he rode his horse door-to-door around the neighborhood, selling his mother’s homemade cheese for 10 cents a tin. He also helped tend to his family’s chickens, goats, and horses. He felt a kinship with animals, as they did with him. Years later, at his house in San Antonio, stray cats, dogs, and even a forlorn pig showed up at his doorstep.

My grandparents happily occupied a shack in their little corner of La Escuadra, where Grandpa’s mother and brother also lived in a second shack. But with the births of the first two children, Rebecca and Carlos, it became clear they had outgrown it. Looking for more money and better job prospects, Grandpa had his eyes on Texas.

He came to the United States on the afternoon of May 4, 1954, when he was 25, leaving his wife behind in Mexico until he could find work. After taking a train to Laredo, he made his way by bus to San Antonio, where his sister Lilia was living. He landed a series of restaurant and construction jobs, saving as much money as he could. A year later, my grandma and their two young children followed him to Texas. As their family grew, they traveled together to Germantown, Tennessee, a Memphis suburb, where Grandpa trained polo ponies. Then they spent summers driving through several Midwestern states, where they worked as seasonal migrant farmers, picking cherries, strawberries, and tomatoes. My mom, Raquel, was the last of their eight children and missed out on all the hard labor.

In the early sixties, Grandpa took a job at the San Antonio Zoo, feeding the animals and cleaning their enclosures. Among hippos, elephants, and tigers, he was profoundly at ease. He’d put on impromptu shows for visitors, even sticking his head between a hippo’s jaws right before it clamped down on its food.

Not long after Grandpa started working there, a two-day-old lion cub was donated to the zoo, and the zoo needed someone to take him home until he was old enough to live in captivity on his own. Grandpa’s reputation as an animal whisperer had grown, and zoo officials asked if he’d be interested. He said yes.

He named the cub Simba (Swahili for “lion”) long before anyone associated the name with The Lion King. Simba slept in my grandparents’ bedroom in a milk crate, and every day he’d plop down in the passenger seat of Grandpa’s pickup truck, sticking his head out the window like a dog. When the pair returned home in the evenings, the kids would invite their friends over to play with the cub.

As the cub grew older and had to live full-time at the zoo, Grandpa was the only person Simba trusted to enter his den. When the two of them were there and others entered, the lion would often rear up on his hind legs as if to protect Grandpa from intruders. Even as Simba began sprouting a mane and put on a few hundred pounds, he would still play as he did when he was a cub, nibbling on Grandpa’s arms without biting down.

Unfortunately, their time together was cut short. After an unpleasant incident with a world-renowned Italian elephant trainer, my grandpa was fired from the zoo. But that’s a story for another time.

Though I relished hearing the stories of Grandpa’s lion-taming antics, I didn’t get to witness them. By the time I was born, he had retired. I spent most of my days with my grandparents, my sister, and my cousins at the little green house. When I attended Las Palmas Elementary, on the West Side, my grandparents would get there early in the afternoon to pick me up, ensuring no one beat them to the prime parking spot under the shade of a tree.

Then came Sundays. I never questioned the tradition; I just grew up knowing there was no sense in making plans that day. Our extended family would make its weekly pilgrimage to the little green house, and there, I’d hear everyone else’s stories about him too.

I learned about the time my grandpa’s truck flipped over while he was driving alone. At 68 years old, with two broken collarbones, he kicked out the windshield to escape from the vehicle. I heard about the time back in Mexico when he used branches to kill two angry rattlesnakes that were blocking his path. He later had them skinned and made into a belt, which he would break out on birthdays or Easter Sunday.

Grandpa taught us to be fearless. No one in my family became Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts, because we didn’t need to—Grandpa taught us to work with animals and enjoy the outdoors. At his six-acre ranch in Somerset, a few miles southwest of San Antonio, we got crash courses in knot-tying and horseback riding and collected pecans, chiles, and mesquite pods. Throughout elementary school, I would brag to my classmates about pet goats, peacocks, and our prized emu. (That’s another story: Once, on the way to his ranch, Grandpa spotted the five-foot-tall bird, which had escaped from a nearby property and was darting around the dirt access road. He grabbed the rope he always kept on hand, and the emu was quickly secured in the back of his truck and on its way to a corral on his property.)

Dancing With the Devil

According to eyewitnesses, a dancing devil with chicken feet was seen at the El Camaroncito nightclub, in San Antonio, on Halloween night in 1975. The handsome stranger reportedly escaped through the men’s bathroom, leaving behind a cloud of smoke and the smell of sulfur.

When I was in middle school, my family moved a few miles north of San Antonio, which was too far for my grandparents to pick me up every afternoon. But I still spent Sundays and summers back at their house with my sister. Though my grandma wasn’t as obvious about playing favorites among the grandchildren, Grandpa always let me and my sister know we were special. No matter how old we got, the bottom drawer of the fridge was always stocked with cans of Jumex, and a plastic bag full of cans of Pringles was always slung around the back of the kitchen chair, both waiting there exclusively for us. Even if the house was crowded, we were the only ones to whom he would offer tortillas con mantequilla.

A few years ago we lost my grandma. Though she stood barely five feet tall, she was the rock of our family, and her absence changed my grandpa. Unlike his wife, who was a devout Catholic, Grandpa was a staunch agnostic who frequently criticized religion, especially TV preachers. But after her death, he began to speak hopefully about the afterlife. “If there is a heaven, at least I’ll get to see my tapita again,” he would say. To our surprise, he stepped into the roles she’d always filled, making us breakfast and cooking us tortillas. Before long, our Sunday visits to what we had always thought of as Grandma’s house became visits to Grandpa’s house.

Early last year, my mom called to tell me that Grandpa, who was 89 years old, was seriously ill.

Life without him wasn’t something that I’d ever prepared for. And even after that first call, I denied that it was a possibility. If there was anyone who could beat whatever silent war was raging in his lungs, it was the same man who had chased after the devil, the same man who had quit smoking, cold turkey, years earlier.

Throughout college, I’d come back to San Antonio once or twice a month, sometimes begrudgingly. But after Grandpa got his diagnosis, the time that passed between those ninety-minute drives felt like an eternity.

Grandpa’s cigarettes were a fixture of my early memories. Entering his room had meant stepping into a haze of smoke that surrounded him in his favorite chair as he watched his novelas. Feeling a bit overzealous after graduating from my elementary school’s DARE program, I’d set out on a campaign to get him to quit. Though I sometimes sneaked packs of cigarettes out of his front pocket, it was guilt that seemed to work the best. I’d beg him to give them up, incentivizing him with memories we hadn’t made yet: my high school graduation or my sister’s first day of kindergarten. He playfully argued with me, letting me know he was an old man who would leave us one day soon, whether he smoked or not.

He was always better prepared for that day than I was.

Grandpa was eventually diagnosed with COPD—a chronic pulmonary disease that worsens with time and makes it difficult to breathe—and he was presumed to have lung cancer. The doctors said they couldn’t say for sure because he had declined a biopsy.

I had been living in Austin for four and a half years when he was diagnosed. Throughout college, I’d come back to San Antonio once or twice a month, sometimes begrudgingly giving up new experiences and time with new friends. But after Grandpa got his diagnosis, the time that passed between those ninety-minute drives felt like an eternity.

The first time I came home after he fell ill, he was in the same chair as always but this time sitting beside an oxygen tank and a nebulizer, neither of which he relied upon yet. Before the next visit, I was warned that he might look a little different, and I came home to find him looking more gaunt but joking and laughing as usual between bouts of coughing.

Then, one day, I was returning to Austin from a hike at a nearby park when I got a text from my dad that Grandpa was in the hospital. I drove to San Antonio in a daze, propelled forward only by my fear and by my frustration that I couldn’t control what was happening to him.

Afraid that I might never hear his voice again, I opened my phone’s recording app as my sister and I entered his room, in hopes that I would capture the greeting he always welcomed us with. Like clockwork, he said, “¿Dónde están mis bebitas del mundo?” (“Where are my baby girls—my whole world?”)

He never got to go home again. He started sleeping more and eating less, and as he declined, our extended clan became the family of the hospital staff’s nightmares, with various aunts and uncles taking shifts so Grandpa was never alone; one day, 68 people stopped by to see him. The nursing staff placed a smiling sun sticker above the doorframe—we later learned this was a hospital code that let the nurses know to be on their A game because there were a lot of eyes on them.

In late April, when we moved Grandpa to a hospice center, we overran the place, filling the halls with the aroma of jalapeños for fresh salsa and a whole cooler’s worth of brisket. We leaned on one another for comfort, but during this last month of his life, it was devastating to see our superhero, the larger-than-life legend we had spent our lives idolizing, lying in a hospital bed.

My grandpa’s funeral was on May 1, 2019, his ninetieth birthday. In the months before his death, he’d told his friends and family to save the date, joking, “It might be my birthday, it might be my funeral, but either way you’re invited.”

For the last seven years of his life, up until his hospitalization, Grandpa would go to the San Fernando Cemetery almost every day to neaten up the area around his wife’s grave and then the grave of his daughter Blanca, whom he buried when she was 46. The drive to take him there to join my grandma and my aunt was especially painful. The funeral procession made its way past his house, where his pickup truck was parked in the driveway, through his West Side neighborhood, and then past the elementary school where he and my grandma had picked me up after school nearly every day, until finally we arrived at the cemetery.

The roads at the cemetery are narrow and uneven, and on the afternoon of May 1 it was difficult to get by the dozens of cars belonging to everyone who had come to lay my grandfather to rest. Someone later told me they hadn’t seen a funeral procession so large since attending the service of an Air Force general. A group of mariachis gathered at the base of Grandpa’s grave, singing “Las Mañanitas,” a song traditionally sung at birthdays. My family had spent the previous night regaling visitors with stories about him, but now, as each of us approached his lowered casket, we did so silently, tossing in a handful of dirt in a final goodbye.

Ask any Mexican, and they’ll probably have a story to tell about the time their family member or friend met the devil or La Llorona or some other demonic ghost. I’ve often joked that our culture is morbid, but the truth is, we tell these stories in order to survive.

My grandfather came from dirt roads in Mexico, and together with my grandma, he built a life that was truly remarkable. Every story they told us, no matter how fanciful, had its roots on the other side of the border. Each story told us something about their place in the world as first-generation Mexican Americans. If Grandpa was unflinching in the face of the devil and could tame wild animals, then of course he wasn’t afraid to start over in a country where he didn’t speak the language, and of course he could laugh in the face of his own impending death.

Everyone in my family is a descendant of those same dirt roads. We’ll each eventually face our own demons and tame our own lions, but we’ll know it’s possible because someone did it before us with the same stubborn Peña fight that runs through our veins.

Our accomplishments and failures are a continuation of the story that my grandparents began. And though some of the details might fade with memory, the stories will remain. They’re the ones I’ll tell my friends and share with my younger cousins when they get a little older. And one day, maybe on my front porch or under a pecan tree of my own, I’ll tell my children the story of Carlos Peña, the man who played poker with the devil and lived to tell the tale.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Longreads

- San Antonio