Any Texan can have a career. But few can make a career out of being a Texan. It’s a short list, and there’s no room at the top, where—for almost three decades—the number one position has been occupied by Bob Phillips, the state’s very own Charles Kuralt. Phillips is the host of Texas Country Reporter, a weekly paean to the pull of the two-lane blacktop and that great natural resource, the small-town character, and the show’s title is synonymous with his name.

Other Texans have earned their livelihood mining the lode of Texas folklore, including newspaper columnist Frank X. Tolbert of Dallas, best known for his expertise in chili-ology, and Houston’s Ray Miller, who hosted the state’s first televised travelogue, The Eyes of Texas. Phillips shares with his predecessors many things: a love of history, a fondness for small towns, and a strong streak of Texas pride. But he adds something extra. “It’s all about passion,” he says. “Somebody could be welding widgets, and he would make a story if he was passionate about it.” What makes the TV show special, though, is not his subjects’ passion but Phillips’ own. He is as crazy about being the Texas Country Reporter as they are about skipping stones, making syrup, repairing accordions, or painting pictures on toilet seats.

On a saunalike day in mid-August, the fifty-year-old Phillips has arrived in the fetching burg of Jefferson to film a segment for the show’s thirtieth season. His destination is Beauty and the Book—the nation’s only combination beauty salon and bookstore, according to owner Kathy Patrick. Tall and talkative, Patrick easily exceeds Phillips’ minimum-passion requirement; she also heads up the Pulpwood Queens of East Texas, a tiara-wearing, RC Cola-slurping book club that has lured more than eighty authors to this remote corner of the state for readings and signings. With what he calls his fellow “back-roads hooligans”—senior producer Jason Anderson, production manager Martin Perry, and photographer Gene Bryant—Phillips fearlessly enters Patrick’s bastion of femininity, which is full of oddities such as Andy Warhol dolls and a lipstick-shaped piñata. Two walls of shelves display current best-sellers, children’s classics, and the work of Texas authors.

As Patrick and various friends—who are there to provide moral support and vie for bit parts—chatter in delight, Phillips and company scope out the salon. Everyone is immediately on a first-name basis, and the teasing isn’t just hair-related. (“Did you see my rings, Bob?” asks Mary K. Rex, extending a hand encrusted with jewelry. “I saw ’em from the road,” he replies.)

Phillips will add voice-overs in postproduction, but while on camera, he wings it without a script. In his instantly recognizable baritone, he proposes a first line: “In most big-city bookstores, you can get something to read along with a decaf latte.” Anderson immediately punches it up: “Make it ‘an extra-tall, half-caf mocha latte with no foam.’ ” Phillips grins, adjusts the wording, and forges ahead: “But here on the back roads, they do things a little bit different.” Anderson breaks in again: “How about, ‘They have their extras too.’ ” Again, Phillips agrees and repeats the line perfectly, including the tongue-twisting coffee description.

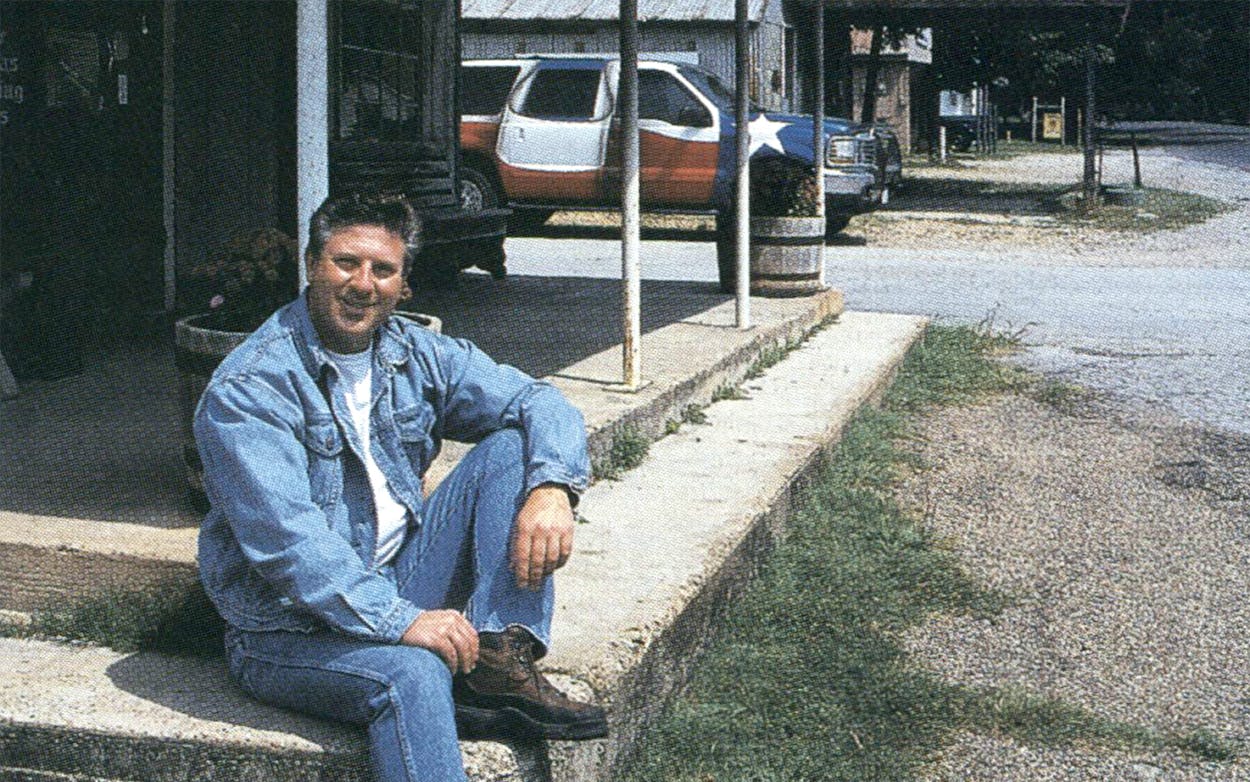

Dressed in his trademark denim shirt and jeans, both perfectly pressed, Phillips delivers his lines flawlessly on the first take. Next up: footage of Patrick shampooing Rex’s hair. The scene might be any beauty shop anywhere, except for Patrick’s attire: She’s wearing a shoulder-length silver wig and a purple cowboy hat. “You realize not everyone dresses like this when they cut hair,” Phillips says. “I hope not,” Patrick retorts. “There’s not enough room in Texas for the both of us.” As Perry, who is shouldering the bulky video camera, moves with balletic grace around salon chairs and sinks, stylist and client yak about subjects ranging from what’s for dinner to which celebrities could be honorary Texans (“Fergie could. She’s got lots of hair, and she likes to eat”). When Patrick notes that “everyone who comes in stays at least an hour,” Rex grins, holds up her index and middle fingers, and mouths, “Two.” Phillips and Anderson beam; such unexpected moments are pure gold.

“They’re naturals,” declares Anderson when Perry calls a halt. Sometimes Texas Country Reporter’s crew members spend four or five hours reassuring a hog caller or soapmaker or pickle packer before they ever start to shoot. Patrick’s on-camera comfort level makes the day-long shoot proceed seamlessly. She conditions, rinses, blow-dries, and back-combs Rex’s hair (“How close to God do you want to be today, honey?”). When filming stops, the general conversation grows a tad raunchy, turning to the supposed correlation between the size of a man’s hands and a certain other body part. “You know, in barbershops we just talk about sports,” Phillips says, adding with a look of mock despair, “Thirty years with a G rating, and we lose it in an East Texas beauty salon.”

As the crew breaks for lunch in Patrick’s house, which adjoins the salon, the talk turns to food—”a subject of universal appeal,” Phillips says. In fact, the Texas Country Reporter Cookbook is one of four books his production company has issued since 1993: “We invited viewers to submit recipes, and we got five thousand responses. Most of ’em came from Mama or Grandma—family-tested and approved.” Phillips knows about family approval. He credits his success to his mother, who is 76, and his father, who died in 1997. “When we first started, I would bounce every idea off them. If it made my mother cry and my dad kept talking about it, I knew it would work.” Phillips’ father ran a service station in Dallas; his mother was an executive hotel housekeeper. But his life was far from totally urban: The family spent weekends and holidays at an aunt’s farm in Whitesboro. It was there that he developed his addiction to all things rural. While attending Southern Methodist University, he landed a gofer job at KDFW, Channel Four, making $2 an hour. He liked it so much that he worked there all through college—full-time.

Texas Country Reporter got its start in 1972. “At the time, I was doing both photography and news reporting for Channel Four, ” Phillips recalls. “I had covered all kinds of stuff, including the Republican and Democratic national conventions. But I didn’t like hard news—still don’t.” He approached his producers and proposed a statewide series similar to Charles Kuralt’s On the Road, which had been on the air since 1967. “I knew the idea would work, but I had to pitch it over and over,” he says. “Finally, they let me give it a try.” He served as cameraman while the station tested a trio of hosts, none of whom lasted long. Phillips—then a mere 21 years old—became the fourth, and his soothing voice and likable demeanor made the show a big success and him an instant personality. Even Kuralt was a fan. “I was at home one day with a horrible flu; I sounded like death warmed over,” Phillips says. “The phone rang, I answered it, and a voice said, ‘Hello, Bob? This is Charles Kuralt.’ I said, ‘Okay, who is this?’ thinking somebody at work was playing a joke on me.” Subsequently the two became friends and frequently compared notes.

Phillips was riding high. But in 1986, without warning, KDFW executives canceled the show. As complaints flooded the station’s switchboard, rival WFAA jumped at the chance to sign him up. Within days Phillips was back in business, and within the year he had formed his own production company. Today the show airs on 22 stations and reaches at least half a million viewers. The Web site gets five thousand hits a day.

After sandwiches and soft drinks, it’s back to work. While Bryant shoots exterior scenes, Phillips and Patrick settle in for the one-on-one interview. Anderson calls for silence and warns the salon gang, “Don’t look at her,” lest she glance away and disrupt the intimacy of their tête-á-tête. Again, Phillips launches into his questions with no notes or rehearsal. His genuine interest puts her at ease, and she answers from the heart; Anderson, staring at the carpet, nods in satisfaction at her responses.

This evening’s meeting of the Pulpwood Queens is fast approaching. Before the crew members shoot footage of the book-loving belles, they set up for the closing sequence: Phillips undergoing a pedicure, complete with nail polish. “Metallics are big right now,” Patrick notes. “For you, I suggest chrome. It’s so Dallas Cowboys.” Replies Phillips: “I’d rather have something that says ‘winner.'” They settle on a medium blue to complement his denim look. Newly beautified, Phillips picks up a book he’ll pretend to read in the salon chair. He’s chosen Close Calls by Jan Reid because, he says, “the title suggests how a guy feels about being in a beauty salon all day.” The camera pans from his face to his feet, where Patrick is adding a few finishing touches, then back up again; he grimaces comically as Rex plops a tiara on his head.

The Pulpwood Queens have started to arrive, carrying casserole dishes and craning to get a look at the visiting celeb. The TCR guys take some footage of the noisy gathering, then wrap it up at eight o’clock. After a three-hour drive home, they’ll be in bed by midnight—unless they stumble across another roadside attraction. “We don’t hurry through small towns,” Phillips says. “They’re our meat and potatoes. I think everybody who watches our show is either from a small town or wishes they were. You know Walter Cronkite’s famous closing line ‘That’s the way it was’? Well, we say about our show, ‘This is the way people wish it was.'”