So, we thought, why not put together a book that profiles the people who drove those decades of profound change? Which brings us to the just-published Lone Stars Rising: The Fifty People Who Turned Texas Into the Fastest-Growing, Most Exciting, and, Sometimes, Most Exasperating State in the Country (Harper Wave), a collection of profiles of dozens of notable Texans, ranging from Barbara Jordan to Michael Dell to Selena.

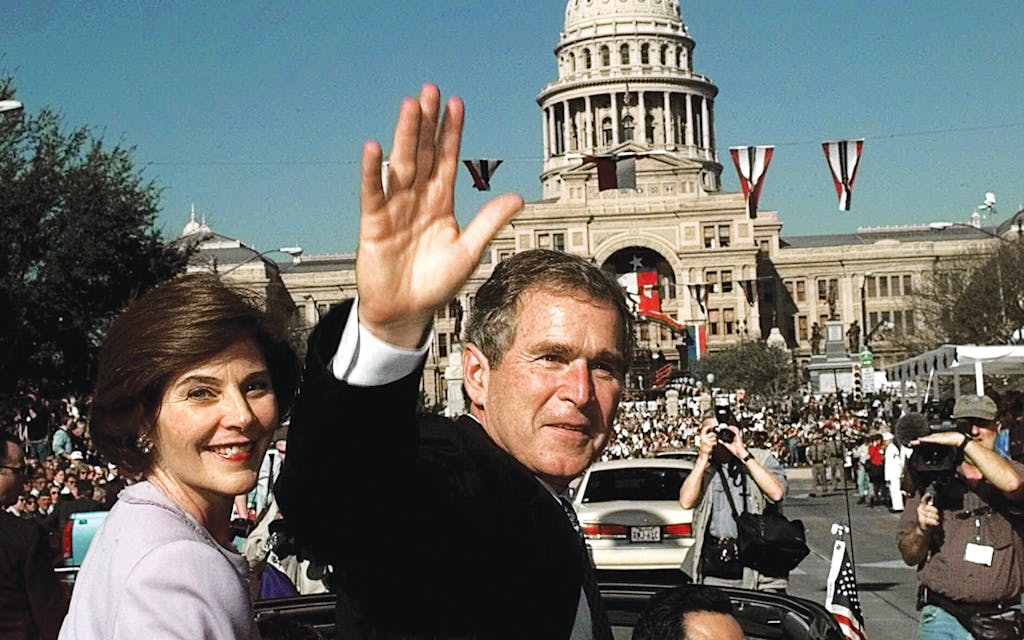

As a taste of what’s in Lone Stars Rising, we’ve chosen former staff writer Robert Draper’s up close portrait of former governor George W. Bush, one of many pieces written exclusively for the collection.

It was on a late morning in 1996, in Texas Monthly’s conference room, that I experienced the rather pungent persona of George W. Bush for the first time. Editor in chief Gregory Curtis had arranged for an hour-long discussion between Bush—then a first-term governor—and the magazine’s editorial staff. Less than two years into his administration, the son of President George H. W. Bush was already regarded as a rising star and likely presidential candidate.

Bush sprawled in a seat at the head of the table, flanked by his advisers Karen Hughes and Karl Rove. Assured by Curtis that our conversation would be off the record, Bush waved off the privilege, saying with a smirk, “Nothing’s off the record.” The topics we raised ranged from the state lottery to environmental zoning restrictions. Bush fielded them with a competitor’s is-that-the-best-you’ve-got alacrity.

The meeting’s understood purpose was to preview the governor’s upcoming second legislative session, following his wildly successful first one, in which Bush managed to sign into law reforms in education, welfare, torts, and juvenile justice. At the top of his to-do list was a sweeping overhaul of the state taxation system that was ambitious in the extreme. Allies had warned Bush that his proposal, which would reduce onerous property taxes by increasing the business tax, was laudable in principle but sure to fail and could throw his political ascendancy off course.

He didn’t care. “I’ve got political capital, and I intend to spend it,” he informed us that morning, his eyes as narrow as his voice was defiant. I came away believing that George W. Bush radiated enough self-confidence to melt down a Geiger counter.

A question that day had gone unasked, by me and by everyone else in the Texas Monthly conference room. Why was Bush hell-bent on so massive (and, as predicted, so doomed) a legislative initiative? Was it really about Texas and taxes? Or was it ultimately about human psychology—the burdens of birthright felt by the eldest son and namesake of a famous father, forever compelled to swing for home runs even when just getting on base would have sufficed?

What seemed audacious back in 1996 foreshadowed a native compulsion that now appears to be an anchor weighing down the legacy of George W. Bush’s presidency. (Though his governorship remains relatively well regarded.) His abhorrence of what he termed “small ball” repeatedly led him into reckless policy pursuits. In 2003 President Bush pushed successfully for a new prescription drug entitlement, known as Medicare Part D, which ballooned the federal deficit and received mixed grades from the studies that tried to determine if it improved the overall health of its elderly beneficiaries. Freshly reelected in 2004, he pressed to partially privatize Social Security—once again crowing about spending his political capital and once again failing spectacularly.

Most infamously, in the wake of the September 11, 2001, attacks, Bush saw what he characterized as an “opportunity”—by which he meant a chance “to not only defend freedom but to make the world more peaceful.” This willful optimism led him to invade a country that had played no role in 9/11 and posed no threat to the U.S. The decision to go to war in Iraq in order to democratize the Middle East now counts as one of the greatest foreign policy blunders in American history.

Well after that first meeting, I was fortunate to spend a significant amount of time with Bush: first, for a GQ profile during his 1998 gubernatorial campaign, as he openly contemplated whether to run for president, and, later, for a book I was writing, in 2006 and 2007, when, as Bush freely admitted to me, “I am consumed by this war.”

Though he loved to promote the one-dimensional portrait of himself as a going-by-the-gut cowboy executive, I found him to be a much more complex figure than he readily let on. Bush could be intellectually aggressive at times, incurious at others. He devoured books (an affinity he shared with his librarian wife), though he often seemed to read into them what he wished.

Bush was a well-liked boss, never one to bully his subordinates, though his frat-boy jocularity took on an edge when he was dealing with Democrats and the media. (Nearly every interview I had with him in the Oval Office began with him making sport of my necktie or scuffed shoes.) He prided himself on doing what he thought was right, irrespective of what polls dictated—though on campaign matters he routinely deferred to the judgment of Rove, who devoured polling data and who occasionally persuaded Bush to put principle aside for the sake of electoral gain. (Bush’s support for a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage comes to mind.)

Up to a certain point, Bush could be a marvel of self-discipline. Throughout his presidency, he faithfully received daily intelligence briefings. He abided by diplomatic norms. He respected the decorum of the office. He was punctual to a fault. (Bush tended to race through his schedule; I always knew to show up to our scheduled interviews a half hour early.) Even his defining error, the decision to invade Iraq, was made over an eighteen-month period and was mindful of pro forma considerations such as first consulting the United Nations and allowing weapons inspectors to do a few short months of work in the country before his patience finally ran out.

What undid Bush’s presidency was his failure to appreciate the seemingly “small ball” stuff. To the new president, Al Qaeda fit in that category. During the summer of 2001, Bush expressed exasperation with the subject of supposed terrorist plots, telling his national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, that he was “tired of swatting flies.” He cut short a CIA briefing on the subject with a dismissive “You’ve covered your ass.” Weeks later, on the afternoon of 9/11, a bewildered Bush found himself asking the same briefer, “Who did this to us?”

It’s a painful irony that Bush, the first Harvard MBA president, rode into Washington with his highly experienced senior staff determined to put on a clinic of efficiency. By the end of 2006, the gross mismanagement of post-Saddam Iraq combined with the slow-footed response to Hurricane Katrina conveyed, instead, an image of incompetence. The culprit was Bush himself: his disinterest in details, his belief in vision over execution, and his aversion to dissenting viewpoints.

Inside the impermeable White House bubble, the president saw himself as “the decider,” firmly on top of everything that mattered. In reality, having an accountable secretary of defense, rather than Donald Rumsfeld, would have mattered. Determining whether Iraq really possessed weapons of mass destruction would have mattered. Seeing to it that hurricane responders actually were doing a “heck of a job,” rather than simply saying so, would have mattered.

Of course, even a two-term governor of a large state whose father had previously served as president and vice president will face a steep learning curve upon entering the Oval Office. Bush got better at the job over time. By the middle of his second term, he was better staffed, less reliant on Vice President Dick Cheney, and more clear-eyed about what he could and could not accomplish.

Though his decision to surge troops into Iraq in 2007 was unsurprising, given his unwillingness to concede defeat, what did surprise was his assiduous follow-through when it came to supporting Iraq’s fragile new democracy. Likewise, when the financial markets melted down in 2008, he acted swiftly to ensure passage of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act and thereby prevent a depression.

How, then, will the dust settle? The answer depends very much on whom you ask. At this moment, the Trumpified wing of the Republican Party denounces Bush with as much vigor as the left once did. Meanwhile, establishment Republicans and many Democrats wistfully cite the forty-third president as a GOP leader who believed in democratic institutions and the rule of law. One thing hasn’t changed in recent years, however: the dark cloud of Iraq still looms over Bush’s legacy, with a majority of Americans viewing the war as a mistake that has made the U.S. no safer, or even less safe.

When I think of George W. Bush, I find much to admire. He never blamed anyone for decisions that were his own. He never held himself up as superior. In one-on-one conversations, he always seemed uncontrived and present. Though he disdained what he called “navel-gazing,” he dared to reveal himself—to talk about the many times he cried while in office and to acknowledge the loneliness of the job. It’s not for me to rank his presidency. If pressed to do so, I would feel confident in saying that there have been those who were decent souls and many others who were not, and Bush fits squarely among the former group.

Recently I found myself thinking about a story I’d heard years ago about then governor Bush. It was told to me by Logan Walters, who had served as Bush’s personal aide during his final year as governor and the fateful first year of his presidency. One morning in New Hampshire, in late 1999, Walters walked into the presidential candidate’s hotel room to tell him that the day’s campaigning was about to begin. He found Bush there on his bed, quietly studying his Bible.

Walters wasn’t exactly surprised when he saw this. Nor was I when he later recounted it to me. It was hardly a secret that Bush was a man of Christian faith. Still, the poignancy of that tableau resonates with me. It serves to remind that there was more to the man than met the eye. Bush never made a show of this morning ritual. He didn’t boast of his piety on the campaign trail. Though he wasn’t above mocking his political opponents, he never demonized them. He knew the difference between belief and performance art. He was who he said he was. I believe this counts for something.

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The George W. Bush I Knew.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Books

- George W. Bush