Russell Lee is one of those fortunate men who has lived to see time favor his work rather than pass it by. He first made his reputation as a photographer of the hardships of rural life in Texas and other states during the Great Depression. In those days he was overshadowed by some of his contemporaries, and since then his work has not been much in the public eye. Few gallery exhibitions and no published collections have been devoted to his work. Nor has he entered the now lucrative business of selling his prints to collectors. Still, respect and admiration for his photography have steadily grown so that now his best work is considered to be, of its kind, second only to that of the difficult but awesome genius, Walker Evans.

Russell Lee came late to photography. After a brief career as a chemical engineer, he took up painting, which he found rather restricting, because, no matter how hard he worked, he couldn’t learn to draw. He was particularly interested in painting the variety of expressions he noticed on people’s faces. At this he failed completely. A few of his paintings hang in his home today, and whether the subject be a nude, a businessman, or a child, they all have the same large eyes and the same unblinking, expressionless stare. He picked up a camera when he was 32, thinking he might improve his painting by learning from photographs. Instead, almost from the first picture he took, he realized he’d found his calling.

He began taking photographs in New York and sold a few to newspapers and magazines. Less than a year later, in the fall of 1936, he learned through the painter Ben Shahn that one of Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies, the Resettlement Administration (soon to become the Farm Security Administration, or FSA) was hiring photographers to document both the agency’s work and the plight of farmers and farm workers, then almost one-third of the national population. Shahn, Walker Evans, and Dorothea Lange were already working on the project. Russell Lee took his photographs to Roy Stryker, the head of the project, and a few months later he joined the ranks of the FSA, ranks that would also include such noted photographers as Arthur Rothstein, Marion Post, John Collier, Jr., John Vachon, Jack Delano, and Gordon Parks.

No one could have suspected what these photographers would accomplish. The photographic project was the work of an obscure office in a huge bureaucracy and its purpose was essentially propaganda. The pictures were supposed to convince critics of the New Deal that conditions were so bad that government aid was absolutely necessary. But their success as propaganda was greatly overshadowed by their impact as art. The work of the FSA photographers holds a major place in the history of photography. They were not the first documentary photographers, but they were the first ones to whom this term was applied and the first ones to attempt documentation on such a grand scale—the daily life and habits, the houses and barns and fences, the land and faces of a whole people. This photographic record is made up of thousands of photographs which are also individually powerful. Something about the period—the people, the poverty, the sense that these people represented America’s past, not its future—especially inspired all the photographers on the project. With the possible exception of Ben Shahn and Gordon Parks, none ever surpassed the work they did during the five brief years of the project’s life. Most of Russell Lee’s photographs in this selection were taken then.

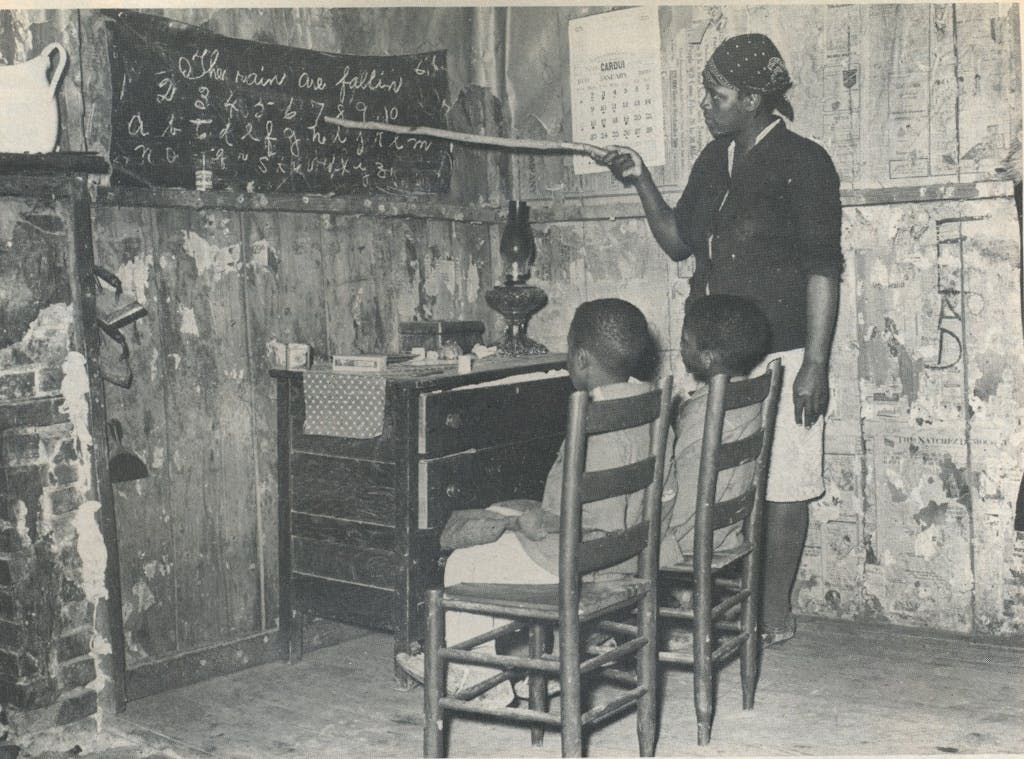

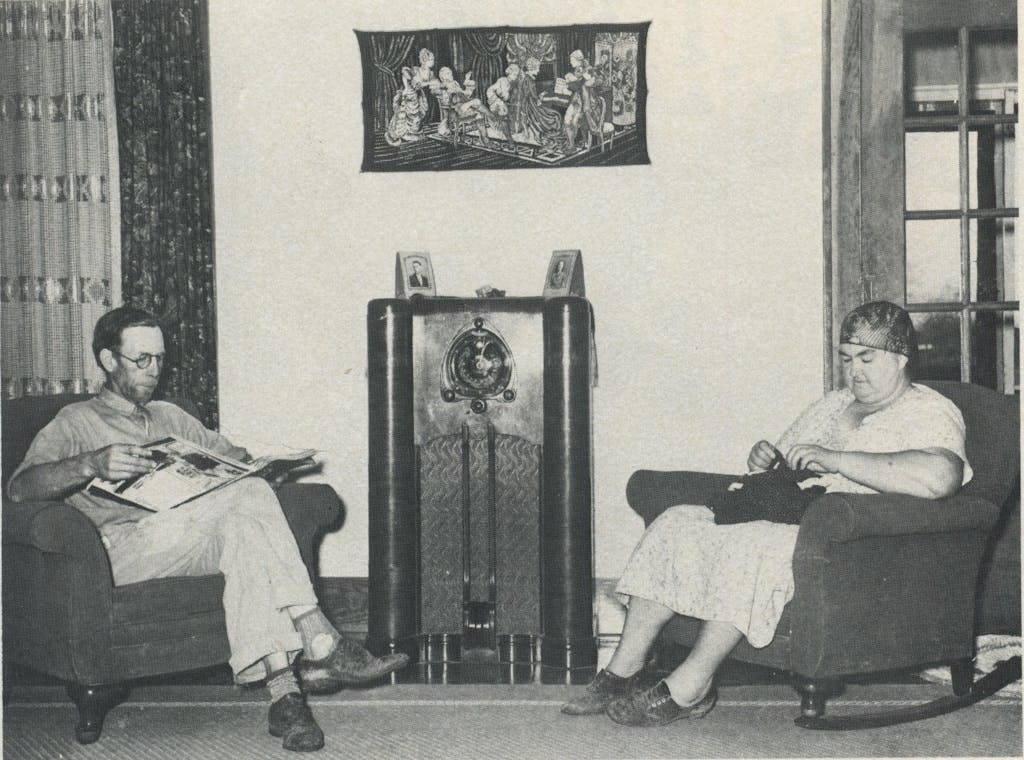

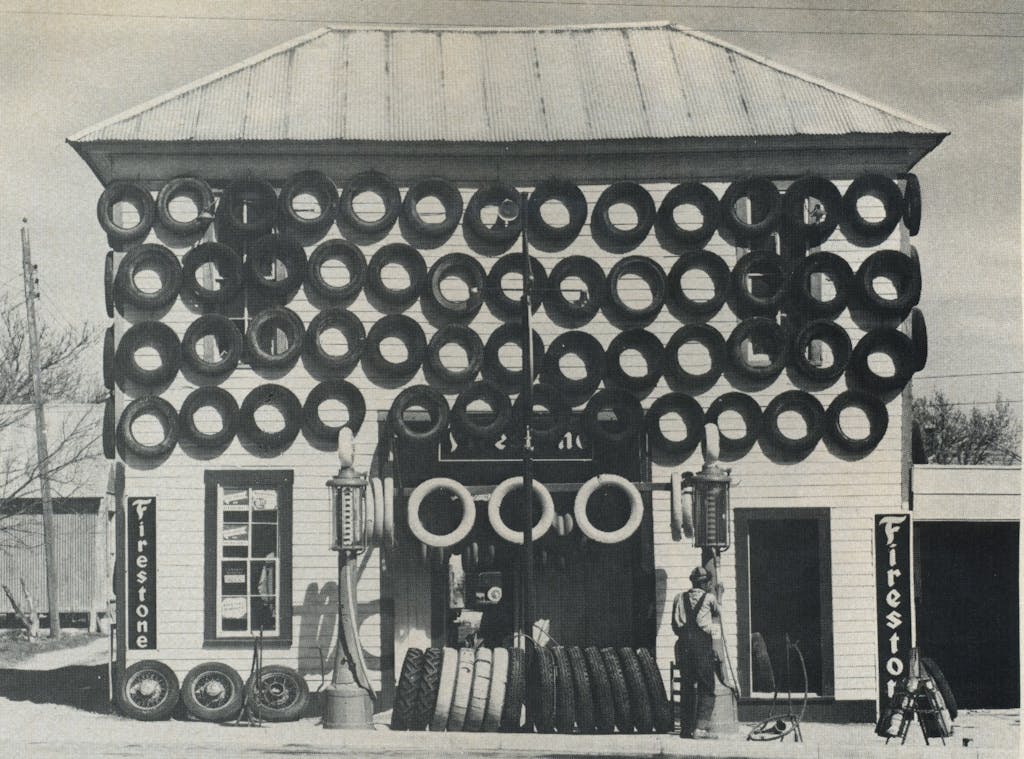

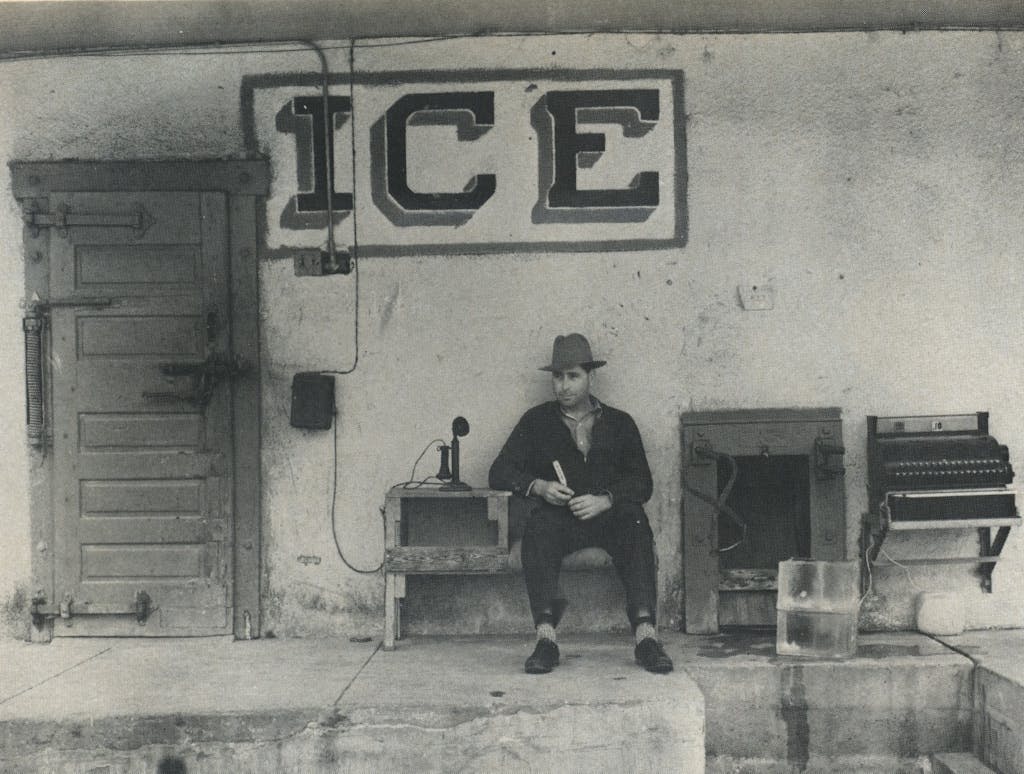

“We wanted to do good reporting,” Lee says now about his time with the FSA. “That was the main thing we stressed. We researched the area and the people we were photographing beforehand and, after that, we just tried to be good reporters.” Lee quickly discovered that small detail—the objects on a table, the decorations on a building—often made the most revealing subjects. He would, when, say, invited into someone’s home, look for clues that would suggest pictures. “In one tenant farmer’s house I saw a bureau with a mirror and I asked this little boy what he did at that mirror. ‘I comb my hair,’ he said. ‘Let me see,’ I said. So he walked over and showed me.” The wonderful photograph on page 91 is the result.

During his work for the FSA, Russell Lee first visited Texas. He liked the hill country around Austin so much that he moved there shortly after World War II. He worked as a commercial photographer as well as for Fortune, the New York Times, the Texas Observer, and Texas Quarterly. He began teaching first in workshops at the University of Missouri and then, for ten years, at the University of Texas. He also shot pictures just for himself. From these come the later photographs in this selection.

Most of these photographs, even the ones taken after the Depression, are about people enduring. This is, of course, a frequent theme in art and literature. What separates Russell Lee’s work is his perception that manners, habits, and private ceremonies, not vague platitudes like “the indomitable human spirit,” are what make enduring possible. Such ordinary, habitual acts like combing one’s hair, dancing, or sitting in an easy chair by the radio would not at first glance seem very powerful forces against hardship. But these photographs show clearly that they are. In fact, the sense of calm in Lee’s photography is actually a state of tense equilibrium. He doesn’t show poverty overwhelming people or people conquering poverty, but the precise point at which manners and habits and social bonds meet adversity and keep it from going any farther.

Russell Lee is now preparing a retrospective of his work for publication. The sampling of his photographs on these pages hints at what an important book that will be. — Gregory Curtis

- More About:

- Texas History

- Art

- Photo Essay