When I asked the cemetery receptionist if I could spread my brother’s ashes on the adjacent Dickinson Bayou, she looked horrified and covered her ears. Chris had asked that his ashes be deposited “in the bayou behind our old house.” He meant our family home in Dickinson, about a half-hour drive northwest of Galveston. Along with our two younger sisters, we’d grown up in a rambling ranch house on a heavily wooded tract directly across the bayou from the Catholic cemetery. No one had answered when I knocked on the door of our old place to ask permission of the current owners, so I thought the cemetery’s waterfront might serve as a substitute for our former backyard, with its canopy of oak trees and Spanish moss.

A pleasant woman summoned by the distraught receptionist told me, “As the director of a Catholic cemetery, I can’t let you spread his ashes here.” (In 2016, the Vatican issued guidelines stating that “it is not permitted to scatter the ashes of the faithful departed in the air, on land, [or] at sea.”) “But,” she added, with a hint of conspiracy, “as a human being, I have some suggestions.” She mentioned accessing a public waterfront downstream or using a boat.

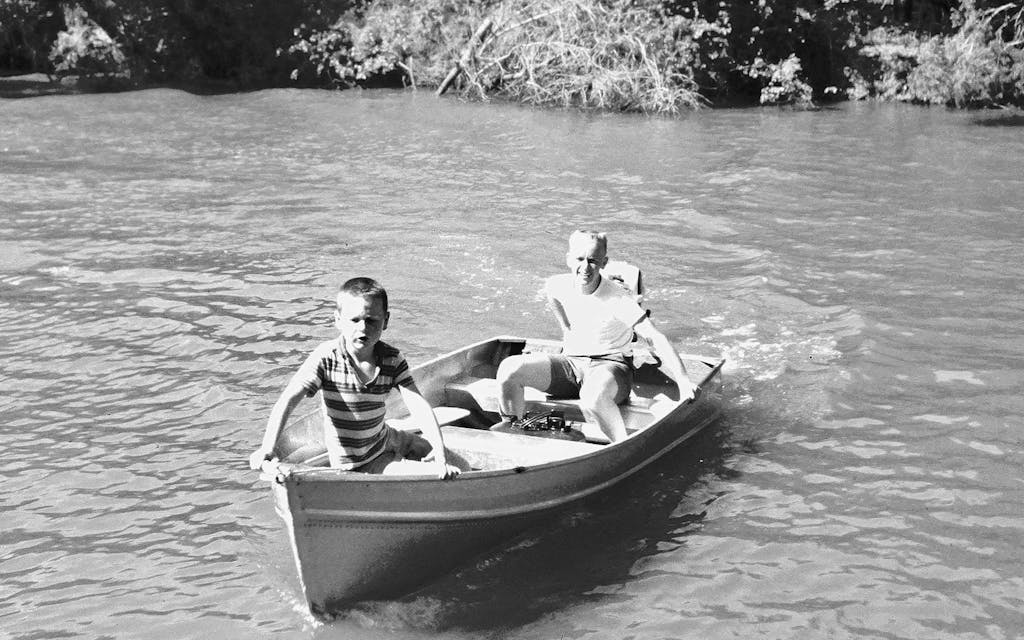

At first, I found it more tragic than bittersweet that Chris wanted his ashes spread in the bayou. I wondered if it meant that throughout his adult life, he had never formed a strong connection to another place. Always a renter, he never owned property. But being back on the bayou reminded me that it flowed into Galveston Bay and then on to the Gulf of Mexico and beyond. To young boys who could operate boats long before cars, the bayou meant freedom. It was there that we encountered those mostly innocent, early brushes with guns, snakes, alcohol, and independence. The bayou had been the backbone of our then-unincorporated hamlet, flowing east toward the bay. It enabled us to visit friends across town without hitching a ride from Mom. Alligators populated the waterway and served as the mascot for the local high school, the Fighting Gators. The nocturnal predations of alligator gar, prehistoric creatures that grow to seven feet or greater, were always visible by flashlight beneath the old wooden bridge just downstream. The sight of 25-pound nutrias—South American water rats with bright orange teeth and webbed feet—was common at low tide. The bayou served as a reminder that while we humans may have evolved, an exhilarating primordial world remained in our own backyard. For two adventuresome boys, it was a swampy paradise. Now we both would be returning to the place that had most shaped us.

We often described Chris as a recluse. To my knowledge, when he fell ill in 2020—a persistent cough leading to a diagnosis of stage IV lung cancer—no visitor had been inside his Austin apartment for at least five years, perhaps more. He even had an arrangement with the management to forgo custodial visits. But in his final days, and in the weeks after his death at 72, I learned that there was nothing simple about his social orbit—or, for that matter, his emotional and spiritual life. I learned that unexpressed love and affection did not signify a life absent of them. Chris had complex relationships, the contours of which went largely unarticulated.

After his diagnosis, my wife and I brought Chris across town to our Austin home, where he had attended family gatherings. The guest bedroom was on the second floor. We installed a chair halfway up the staircase for him, breathless, to collapse in on his way up. Chris had, to my knowledge, never cohabitated with another person as an adult. He would call out, “Can!” That was our cue to deliver a can of 7UP or Sprite. We got a perfunctory thank-you, if that. We knew that he had not acquired the niceties that lubricate the hinges of domestic life, and it was hard for him to accept help. After a couple weeks, a hint of resentment crept into the house. I’m ashamed of that now.

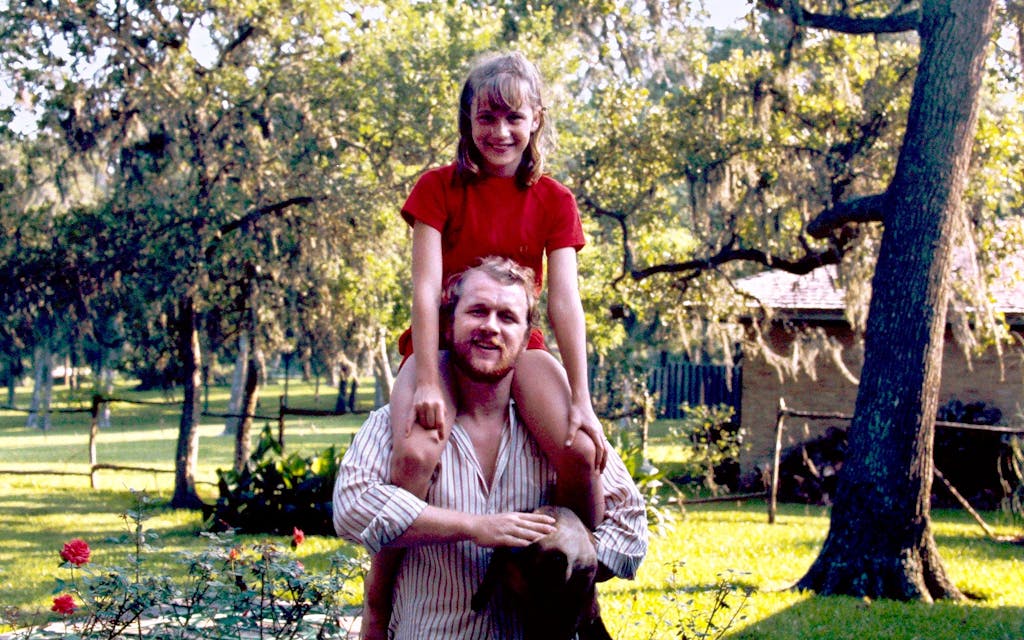

While still a teenager, Chris possessed the blond ringlets and broad shoulders of a leading man. In high school, with his hair dyed black, he was cast by the Houston Grand Opera to play a silent Roman soldier. Women found him attractive, and he had a certain bravado that animated his social interactions. After studying economics in college in New York, where he worked part-time at a Manhattan radio station, Chris attended law school in Austin. One semester shy of graduating from the University of Texas School of Law, he dropped out. He ended up spending most of his working life in the printing trade. I think he enjoyed the intellectual aspects of law far more than the prospect of actual law practice.

Almost four decades later, even with gray hair, he looked Shakespearean, and the cancer had reduced his weight to that of his days on the opera stage. But he was fragile and needed help, which we did our best to provide.

Five weeks elapsed between the first chest X-ray and Chris’s death in a hospital. The night before he died, I had questions for him about his affairs. Funeral, obituary, possessions, money, people to be contacted, the normal things. He declined all the ceremonial elements. “Is there anyone you want to talk to?” I asked.

“Gloria,” he said in just above a whisper. I knew of Gloria, a pretty girlfriend from high school, and I knew he’d kept in touch during the intervening decades. I got her on the phone from California, and my wife and I stepped out of Chris’s tiny room in the intensive care unit. But I could hear much of his side of the conversation.

“I want you to know the reason I let you go,” he told the startled Gloria, who was then seventy. “It was because I wasn’t confident that I could be a good husband, a good provider, a good father. . . . But I never stopped loving you.” This declaration of love, spoken through tears and uttered from his deathbed, was hard for me to hear. And I could only imagine what Gloria, long a wife, mother, and grandmother, was thinking. Chris died about nine o’clock the next morning.

I was executor of his estate and would learn a lot more about my brother in the weeks ahead. I found correspondences that he had kept with several women, although I don’t know the exact nature of the relationships. There were letters through the decades from a woman whose Italian surname I recognized because the family was large and prominent in Dickinson. I found her in Sicily. She had acquired dual citizenship and was learning to speak Italian as a kind of COVID project. I’m not sure she had seen Chris in decades, but they had stayed in contact. I found correspondence from a globe-trotting journalist now settled in New Jersey. I called, and she had fond memories of their time together. There was a note from a tennis player describing her success on the professional tour in Asia, signed with only her first name. Still another woman had written a saucy postcard describing her work in a marijuana shop in Amsterdam. Chris’s reciprocal communications appeared to be haphazard—infrequent and unexpected phone calls at odd moments. But in his own way, I believe he loved them all.

Two of these sources mentioned that Chris had told them of his great affection for my wife, Simone, which came as a surprise to me—and to her. Typically gruff, Chris often called her with some kind of funny or outrageous commentary, but never an endearing word. Simone and our two sons loved Chris, and I think he understood that.

In addition to letters, I discovered fifteen thousand books (many handsomely bound and most devoted to philosophy, history, theology, politics, and poetry), about 250 posters commemorating exhibits and concerts (the Grateful Dead, Austin, 1977), and, most astonishingly, more than two hundred crucifixes of every conceivable size, material, and style. Chris said he had not been to mass since 1972, although he often prayed, performing the sign of the cross, before meals. Another relic from his apartment—his LSAT score from 1970, which was in the top 7 percent.

It took three book merchants five weeks to sort, pack, and transport Chris’s books. One recently told me that after two years, she had plowed through about half of her five thousand volumes from his collection. A vintage goods dealer took the posters.

Chris’s acquisitiveness ultimately made him a prisoner of his bedroom. The books and the art filled every room, rendering the kitchen impassable. After much malodorous toil, I discovered that all the food in his refrigerator was five to six years beyond its expiration date. The custom-built bookshelves that lined the perimeter of every room covered the windows, so natural light was scarce. And yet Chris kept acquiring. He was a regular at thrift shops, rare-book stores, and garage sales. The people I encountered after his death said he was quite sociable and entertaining within that curious world of collectible objects. “Everyone liked Chris. He was fun and opinionated,” said one of the dealers.

I was comforted to learn that Chris had indeed found a community. That the old bachelor had maintained relationships with women through the decades. But, sorting through his apartment, I was also overcome with regret. Could I have done something to change the trajectory of his solitary life? To improve the quality of those final years when collecting turned to hoarding and things got out of hand? But I hadn’t understood how his world was closing in on him. And the last thing he wanted was to be rescued by his little brother. I came to wonder if in spite of Chris’s intellect and charm, he somehow felt unworthy of love and domestic happiness. If there was some deep insecurity that made him turn away from the larger world.

Chris’s ashes had been living in our pantry for almost two years, on a shelf above the coffee grinder and the spice jars. He always liked our cooking. I’d placed the ashes in an elegant wooden Christian Brothers wine box I found in his apartment. Chris had graduated from a Christian Brothers high school in Galveston, as well as from Fordham University, run by the Jesuits. Some mornings I would touch the wooden box and wish him good morning as I made coffee. I missed him—and all his eccentricities.

My sister Jane lives in California, and because of COVID, it took a long time for us to coordinate a return to Dickinson. Ultimately, I reached the present owners of our family’s old home and gained access to the backyard. Despite the ravages of time, floods, and hurricanes, the waterfront was resplendent. On a warm, radiant morning last November, my sister, my wife, and I spread my brother’s ashes in the languid current of the bayou. Standing on the boat dock, I read a few words about Chris’s final days and how I wished he’d shared more about his life. I quoted the poet John O’Donohue: “I am lonesome for all the conversations we never had.”

Only a short distance away, inside the Catholic cemetery on the opposing shore, were the graves of our parents. Chris had been right after all. Here, on this stretch of Dickinson Bayou, was where he belonged.