Featured in the San Antonio City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in San Antonio with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the San Antonio City Guide

This story has been edited, since we first published it last month, to correct and clarify issues of accuracy and context raised by two of the people about whom we wrote. Details of the changes are at the end of the story.

Kaye Tucker thought she had come up with a clever idea. If everything fell into place just right, she could accomplish two things at once: transform the Alamo into a world-class historical site and help an aging British rock star clean out his basement.

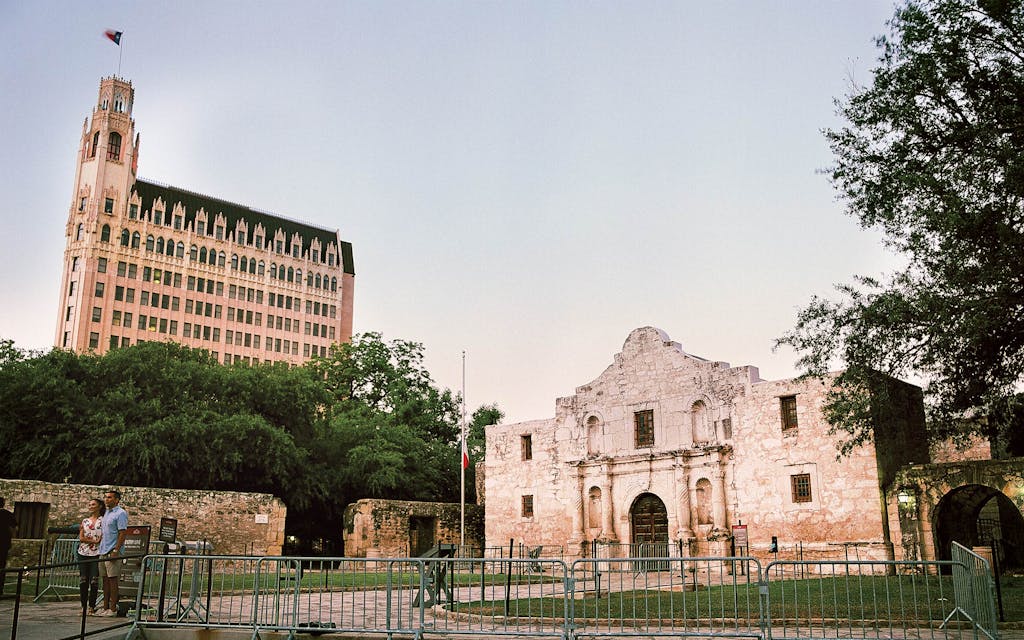

The path to that strange opportunity began about a decade ago, when Tucker was given an important assignment. A mid-level bureaucrat in the General Land Office, she was tasked with helping turn things around at the Alamo, where visitor surveys show that most tourists are disappointed with the outdated exhibits and lowbrow surroundings. In 2011 the Texas Legislature had asked land commissioner Jerry Patterson to shore up the “Shrine to Texas Liberty” after years of neglect by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, giving him $6.5 million for overdue repairs. But Patterson wanted to do more than patch some crumbling walls. He envisioned a first-rate historical museum and an expansion of the site that would approximate the 1836 footprint of the fort—an area that currently houses, among other things, T-shirt vendors and a wax museum, the kinds of fringe businesses found on the Las Vegas Strip or Bourbon Street.

Such grand plans were going to require a lot more than $6.5 million. The bill would almost certainly run into the hundreds of millions. Tucker knew that raising that kind of money from lawmakers and private donors would require a flashy draw.

Soon after she set out on her task, Tucker struck up a friendship with Jim Guimarin, owner of the History Shop, a touristy storefront around the corner from the Alamo. One day, she and Guimarin were talking about how he had spent much of the past half decade helping Phil Collins amass what was reputed to be the world’s most extensive collection of Alamo artifacts. Collins, the front man of the multiplatinum British band Genesis and one of the biggest pop stars of the eighties, had been obsessed with the Alamo since he was a child. But now, Guimarin explained, the wealthy musician was running out of room at his Swiss villa for his sprawling collection. Collins was hoping to find a museum that would display the hundreds of items he’d assembled, including what he claimed may have been Jim Bowie’s knife and Davy Crockett’s shot pouch and what he was convinced was William B. Travis’s knife—objects belonging to the three most famous defenders of the Alamo.

When Guimarin casually asked Tucker if she’d ever met Collins, Tucker said that she hadn’t but that she very much wanted to. And not just because she was a fan who’d seen him in concert back in the day. “We’d like his stuff,” she recalls telling Guimarin, who didn’t seem to take her seriously.

And, in truth, she wasn’t sure how serious she was. The site’s current museum, in the Alamo’s Long Barrack, didn’t have enough room to display Collins’s collection. And the museum that Patterson was proposing for the site was nothing more than a dream. Still, when Guimarin called her one afternoon in February 2014 and asked her to join him and Collins for dinner, she immediately said yes. “What he couldn’t see,” Tucker said much later, “was me jumping up and down on the other end of the phone.”

An hour later, Tucker was sitting in the back seat of Guimarin’s minivan as they pulled up to the Hyatt Regency on the River Walk, where Collins stayed whenever he was in town; he liked to look out his window at the Alamo and contemplate the heroism of the siege. As Collins opened the sliding door and got inside, Guimarin turned and asked, “Phil, do you know Kaye?” Jim, you know good and well I have not met this guy before, thought Tucker, who introduced herself as if it were the most normal thing in the world to meet a pop star in a minivan on the way to dinner.

They headed to El Mirador, a now-closed Tex-Mex restaurant favored by politicos and business executives, in the King William Historic District. The staff always gave Collins a tiny private room in the back, where he could avoid starstruck autograph seekers. After they ordered enchiladas and tacos—Tucker had soup—Collins and another collector who was along for the ride chitchatted about a recent purchase one of them had made. Tucker says she was “just pleased as punch to be there.”

As the meal was winding down, Guimarin turned to her and said, “Kaye, was there something you wanted to talk to Phil about?” Collins, who had already finished eating and was slumping back comfortably in his chair across the table from Tucker, asked what was on her mind.

“I know the reason that you’re here is you’re kind of lobbying for a new home for, you know, your collection,” she stammered. And then, taking a deep breath, she made the ask: “I wondered if you would entertain the idea of giving it to us.”

Collins regarded Tucker with an expression she couldn’t quite discern. “No less than five million things went through my head for what seemed like an hour and a half, but it was probably about fifteen seconds,” she says. “And he looked at me, and he kind of turned his head, and he goes, ‘I didn’t even think y’all would want it.’ ”

“Why would you think that?” she replied.

“I mean, where would you put it?”

Oh, I am writing checks I can’t cash, she thought. Sure, her colleagues at the Land Office had talked about Collins’s collection in a “What if?” sort of way, but it never got past that because, as Collins noted, they didn’t have any place to put it. But sitting there at that moment, across from a man whose songs she had hummed a thousand times, she made a leap of faith—“let’s just say, maybe ignorantly,” she jokes. She told Collins that the Land Office had ambitious plans for the Alamo and that acquiring his collection would be a publicity boon that would help the agency raise enough money to embark on a major building project—one that would include a museum that would showcase his collection.

“I feel like a dog with two tails,” said Collins.

“Is that good?” she asked.

“Oh, absolutely.”

A week later, Tucker arranged for Collins to meet Patterson, and over a

government-budget lunch of sandwiches and Diet Cokes in the Alamo offices, they hammered out the details. Patterson, a self-effacing Texas history buff whose tastes ran more to George Strait than to eighties pop, was excited, not so much because he was sitting down with a musical icon as because he realized what this deal could mean for the Alamo. During their conversation, Collins told Patterson that he expected everything to be displayed in one place, which Patterson agreed to. Patterson proposed that they enter into a contract obligating the state to reach a “schematic phase of build-out” on a “permanent museum and visitor center” by October 2021, or Collins would have the right to take his collection back.

“The contract was, like, three pages,” Patterson recalls. “I signed it, sent it to him, he signed it.” That agreement was publicly revealed a few months later, on June 26, 2014, during a press conference at the Alamo. “This completes the journey for me,” a beaming Collins said. “These artifacts are coming home.”

Patterson shook Collins’s hand, knowing his role was finished. He had lost a recent primary bid for lieutenant governor and hadn’t run for reelection as land commissioner. The hard work of turning the proposed deal into a reality would fall to someone else.

Perhaps that’s why no one on Patterson’s staff bothered to take a close look at Collins’s artifacts, to make sure they were authentic. It’s not, of course, unusual for an organization to accept a donation of historical items without checking their authenticity. What is unusual is for a reputable organization to agree to display a collection in its entirety (as Patterson seemed to do) without authenticating every item—and to commit itself to raising and spending hundreds of millions of dollars to house them .

Patterson left the details to his successor, a young man in a hurry whose family name is, in Texas, even more famous than Phil Collins’s. The new land commissioner, George P. Bush—grandson of one U.S. president, nephew of another, and son of former Florida governor Jeb Bush—took office the following January. He had big political ambitions that a major restoration of the Alamo would bolster.

What he didn’t know, or later, perhaps, pretended he didn’t know, was that while most of Collins’s collection apparently consisted of authentic documents and antiques, certain items may not have been what they seemed. Bush had no idea that he was walking into a battle royal between some very impassioned people that has been going on for years.

Like many boys his age, Phil Collins fell in love with the Alamo in the mid-fifties while watching Walt Disney’s movie Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier. “The memories I have . . . were that this group of people were going—and they knew that they were going—to die,” he said during a panel appearance at the Texas Tribune Festival in 2016. “That just moved me as a five- or six-year-old. From that moment, I was obsessed.” He drew the facade of the chapel on the garden wall of his childhood home, in West London, and recreated the Battle of the Alamo with his toy soldiers.

Even as an adult, Collins nurtured his fascination. In 2004 he traveled from Houston to San Antonio during his First Final Farewell tour to show the Alamo to his wife, his three-year-old son, and his assistant. Afterward, they walked around the corner to the History Shop. Guimarin struck up a conversation with Collins, whom he did not recognize at first. “He was interested in documents, and I had a Sam Houston document,” Guimarin says. “He bought that later, but he left me his information and said whenever I got something, he would like first look at it. He was interested in anything to do with the Alamo.”

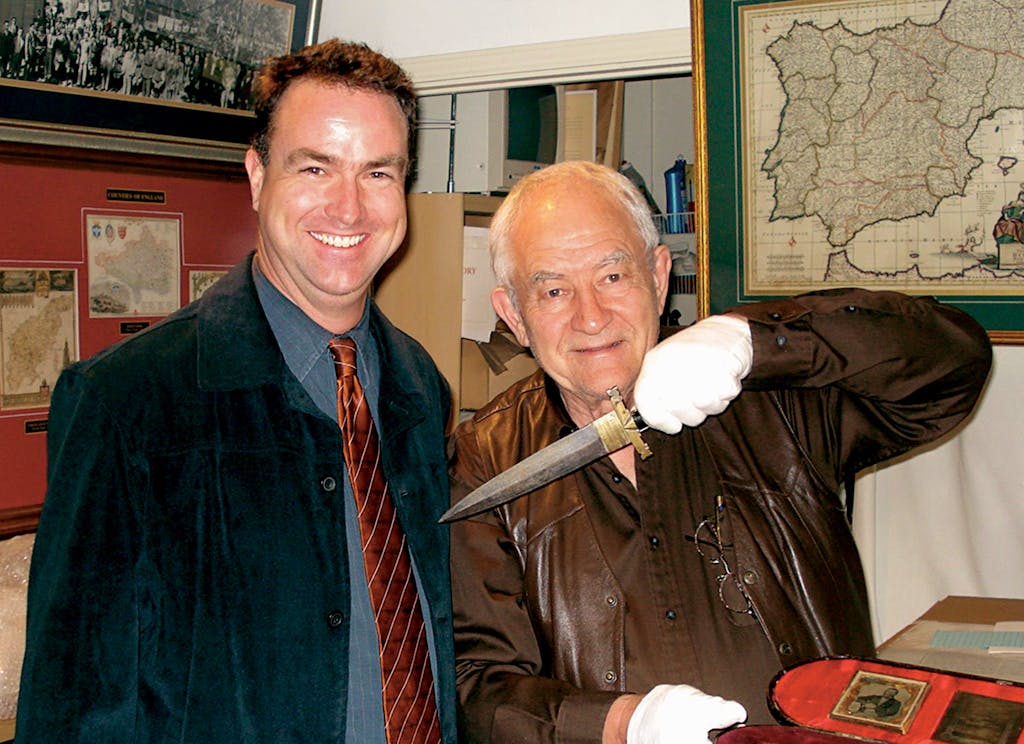

Guimarin, now 86, was never a big collector of Alamo artifacts. In fact, collectors didn’t think much of the History Shop’s minor bits and bobs, such as a Mexican uniform button or a tarnished bronze bullet. Most of his income came from restoring and preserving old documents, books, and maps. Guimarin, though, knew a good customer when he saw one. He started seeking out items for Collins, who complimented him on what he regarded as reasonable markups. The business relationship became a friendship.

Collins was soon buying almost everything connected to the Alamo; first, documents, and then more substantial artifacts. In 2006, to help his top customer fulfill his dreams, Guimarin turned to a young man who hoped to take over the History Shop one day.

Alex McDuffie understood the world of rifles, swords, knives, cannonballs, and historical paintings. Growing up in Houston in the seventies and eighties, the intense and chatty McDuffie didn’t enjoy school very much, but he fell in love with Texas history. His mother gave him the book Thirteen Days to Glory, Lon Tinkle’s fast-paced but historically suspect retelling of the siege of the Alamo. The adventure, chivalry, and sacrifice appealed to McDuffie, who today, at fifty, is still ensconced in that world.

In the late nineties, McDuffie was working for a web-development business when a Houston-area dealer named Alfred Van Fossen hired him to build a website. Van Fossen, who died in 2006, was notorious for selling questionable items supposedly associated with the Alamo. McDuffie, still nurturing his boyhood fascination with the battle, quit the website business to work alongside him.

Most people feel a tingle of excitement when holding an object that played an outsized role in history. McDuffie finds it intoxicating. He often describes feeling the “energy” of a knife or the power of a portrait. He says he can sense when an object is authentic, and Van Fossen gave him a chance to handle such things every day. “He had some really great pieces, but he also, I didn’t know at the time, had a lot of fakes,” McDuffie says. “He was a real scoundrel.”

McDuffie fell out with Van Fossen in 2001 over who was the rightful owner of a painting of Mexican general Vicente Filisola, deputy to General Antonio López de Santa Anna. But McDuffie found a new mentor in Guimarin’s friend Sam Nesmith. An Abilene native born during World War II, Nesmith grew up fascinated with all things military. A heart murmur barred him from joining the Air Force, so he dedicated his life to military history and became curator at the Alamo in 1966. Most of his career, though, was spent at San Antonio’s Institute of Texan Cultures, where he conducted research, developed exhibits, and wrote books about Spanish-colonial Texas. He was also a proud Scot; he wore a kilt for special occasions and bore a passing resemblance to Sean Connery.

Nesmith gave McDuffie some out-of-the-box advice: documents proving an artifact’s authenticity are important, but in the end, you have to trust your gut. “Why do you care what other people think?” McDuffie recalls Nesmith saying. “What do you think? What does your gut tell you?” It was advice McDuffie took to heart. “When I started listening to my own gut, that’s when I really started finding pieces that were just really great,” he says.

After Guimarin started working with Collins, in 2004, McDuffie hired on and began searching for as many Alamo artifacts as he could get his hands on and running them by Nesmith for authentication. The three would produce reports on the objects they found and offer them to Collins for sale.

Guimarin, concerned about the security of the valuable objects he was now stocking, decided in 2007 to install a floor safe beneath the History Shop. There, workers found an adobe wall from the Alamo’s original irrigation canal as well as uniform buttons easily attributable to the Mexican army. Guimarin wanted to dig for more artifacts but didn’t own the building. So one evening, over margaritas at El Mirador, he made his pitch to Collins: Would he be willing to purchase the building and finance a dig? Collins said yes.

Months later, after Guimarin had the deed in hand, workers excavated a six-foot-deep hole down to the limestone bedrock. Then they dug horizontally, and every time someone spotted an object, Guimarin would be called over. He took photos of whatever rusty chunk of metal the diggers found and then carefully extracted and cataloged it. Over the course of nearly a year, the excavation turned up bullets, cannonballs, belt buckles, hat insignia, horseshoes, and three firepits evenly spaced in a straight line, as soldiers might build them. Guimarin says he’s convinced most of the artifacts are from the March 6, 1836, Battle of the Alamo.

What Collins didn’t keep, Guimarin sold. “A lot of people came through, and they’re paying seven or eight hundred dollars for a horseshoe,” Guimarin says. “I sell these things at atrocious prices, but where else are you going to get it?”

Collecting artifacts, financing a dig, and hanging out with a bunch of other men captivated by the Alamo made Collins happy. “I have to say it was one of the most exciting projects I’ve been involved with,” he wrote in his 2012 book The Alamo and Beyond: A Collector’s Journey. “I managed to get my hands dirty on the few occasions I was able to be there, and it was very exciting knowing I was digging in earth not seen since those fateful days back in 1836.” He told the San Antonio Express-News, “Basically, now I’ve stopped being Phil Collins the singer. This has become what I do.”

The four-man team hoovered up just about every Alamo artifact that came on the market over the next decade. Guimarin sold the most impressive ones to Collins, who jetted in several times a year to review their progress. They would enjoy margaritas at El Mirador and walk the Alamo grounds at night. None of this is unusual in the world of wealthy collectors, who have dealers waiting on them hand and foot. Dealers do everything possible to keep such collectors happy, which usually means feeding them a constant supply of objects to satisfy their obsession. And many of these objects come complete with colorful—and frequently contested—backstories.

McDuffie often worked with a man named Joseph Musso, a Los Angeles–area collector he had met during his days with Van Fossen. McDuffie and Collins were interested in one precious item Musso owned: the famed Alamo fighter Jim Bowie’s personal knife.

But whether you believe the knife belonged to Bowie depends on what you believe about how the first Bowie knives were made. One legend goes that Bowie and his brother John started commissioning fighting knives after the 1827 Sandbar Fight, a brawl that took place on an island in the Mississippi River near Natchez. Jim became famous after that melee for using a big, distinctive blade to kill a Louisiana sheriff. The designs for the Bowie knife evolved from a minor variation on a Spanish-style butcher knife into the curved version most people think of today.

As Bowie’s fame spread, hundreds of artisans across the country started approximating the design. So many of these so-called Bowie knives were manufactured that thousands of collectors spend much of their time squabbling about which ones are from what era, who made which knives, and which are fake. Many of them can’t even agree on when and where the first Bowie knife was made. One highly debatable version of its origin states that Bowie created the iconic design in 1830 and paid an Arkansas blacksmith named James Black to make it.

Fast-forward to California in the early seventies, where Musso spotted a handsome Bowie knife at a gun show that looked as if it could date to the nineteenth century. Musso noted that the blade had an unusual feature: a strip of brass that extended from the hand guard to the dip in the knife called the clip. Musso bought the knife for a small amount and says he didn’t think much about it until eleven years later, when he was cleaning his firearms and decided to rub a little solvent on the knife to get the crud off. “In doing so, I found it had the initials ‘J. B.’ on it,” Musso says. “I had to sit down and have a long talk with myself because I knew that I didn’t put [them] on it.”

Of course, there was no proof that Jim Bowie had owned the knife; anyone could have scratched those letters into the metal, including the blacksmith James Black, who also had the initials “J. B.” Musso has hired several companies over the years to determine the age of the knife metallurgically. He says the first report he received revealed that the steel dated to the 1830s and was made in a relatively primitive charcoal furnace. Another lab determined that the brass was consistent with alloys made in small workshops during that era and had trace elements matching those found in a fairly uncommon type of green sand, derived from marine sandstone, that could be found 250 yards from James Black’s Arkansas workshop.

Musso decided to take the knife to a psychic. But because, he says, he doesn’t really believe in the paranormal, he wanted the best: Peter Hurkos, a Dutch clairvoyant who claimed a head injury had given him special powers. “I figured he was the only one I could believe in because he was decorated by a Catholic pope and he was supposed to have an eighty-seventh-percentile degree of accuracy,” Musso explains.

Hurkos, who had worked on the Charles Manson and Boston Strangler cases, agreed to a meeting, Musso says. After Musso handed him a brown paper bag with the knife inside, Hurkos reportedly named the man who had sold the knife to Musso. Musso says he then laid out several photos facedown and Hurkos pointed at one, which Musso then flipped over. It was Bowie’s portrait; Hurkos declared the knife had belonged to him. To Musso, this was just another piece of evidence that would help him build a case for authentication.

McDuffie believes there’s more than enough evidence to attribute the knife to Bowie. Guimarin is more circumspect. “Is it the same kind of knife that he used? Yes, it is. But is it the knife? I don’t know.”

Nevertheless, according to rumors circulating among knife collectors, Guimarin and McDuffie arranged for Collins to buy the knife for $1.5 million in 2011. (McDuffie and Musso both state that that figure is incorrect but have declined to provide an accurate figure.) “I really never planned to sell it,” Musso says. “But I’m kind of grateful that Phil did approach me. And if [the Alamo museum is built], it can be shared with the world.”

The sort of good luck that Musso enjoyed in discovering the supposed legacy of his knife can be found repeatedly when one dives into the provenance of the Collins collection. McDuffie was attending an antiques show a decade ago where a seller offered what he called “an Alamo sword.” The dealer relayed how the nineteenth-century saber had belonged to a Louisiana-based U.S. Army soldier named John R. Johnson who reportedly fought at the Battle of San Jacinto, where, six weeks after capturing the Alamo, Santa Anna and his army were defeated by forces commanded by Sam Houston. According to family lore, Johnson brought the saber home to Virginia as a war prize.

McDuffie’s gut convinced him to buy it. When he got home, he decided to apply a little solvent, just as Musso said he had done with his Bowie knife. “I noticed something on the spine,” McDuffie says. After letting it soak for two days, McDuffie says that he made out an inscription: “J. Bowie.”

McDuffie took it to a metallurgist named Edward V. Bravenec, who put the item under a high-powered microscope. In a report dated Feb. 24, 2014, Bravenec said the saber was of early 19th century vintage and that the inscription “J. Bowie” was covered with score marks. He said those marks were left when the saber was pulled from its scabbard, “which indicated that the name was inscribed before usage.”

Bravenec wrote: “I believe that … the owner was J. Bowie.” He did not make clear whether he believed it was the James Bowie of Alamo fame. And Bravenec offered no opinion as to whether the saber was ever at San Jacinto or the Alamo.

The next question was, Who had found Bowie’s saber? McDuffie did some research and found that John R. Johnson was listed as a deserter from Fort Jesup, Louisiana, in 1836. He says Johnson’s name also showed up on the Battle of San Jacinto muster rolls that same year. McDuffie, claiming “there is no other explanation,” says he is convinced that a Mexican soldier must have taken the sword off Bowie at the Alamo, then, a month later, lost it at the Battle of San Jacinto, where Johnson acquired it. “It’s like the story wanted to tell itself,” McDuffie says.

A little dab of solvent has helped McDuffie make several other significant discoveries. “So many pieces that I’ve bought over the years that they advertise as unmarked, you can’t really make out anything,” McDuffie explains. “But if you put a little oil on it and you take it out in the sunlight and you look at it at angles, a lot of times you’ll find that the engraving—maybe identifying somebody’s name or a maker—is just filled in with grime.”

At one auction in 2010, Guimarin bought a “sword belt” purported to have belonged to Colonel William Barret Travis, commander of the Texians who defended the Alamo. Though the listing, from an Arkansas dealer named Gary Hendershott, stated that there was proper documentation for the item, Guimarin says he never received it. (Hendershott insists he “would’ve sent it.” ) Collins kept the belt anyway, and in The Alamo and Beyond he notes that “it is possibly thought to be” Travis’s belt.

While perusing another auction catalog in 2009, McDuffie spotted a consignment lot from Hendershott that included a pistol, a small knife, and a pouch. Hendershott listed them as a “New Mexican Hunting Pouch, Pistol & Knife, ca. 19th century.” Though he was reluctant to deal with Hendershott, with whom he had a contentious history, McDuffie’s gut told him this could be something special. The pouch was embossed with the initials “E. S.,” and McDuffie says he was convinced it belonged to Erastus “Deaf” Smith, the scout who rode out of the Alamo for help.

McDuffie bought the lot and then applied his solvent technique to the knife. He says the initials “W B T” revealed themselves, and he believes they stand for William Barret Travis, who he theorizes gave the knife to Deaf Smith when he left the Alamo, seeking reinforcements. (McDuffie also suggests an enslaved person may have given the knife to Smith after the battle.) Collins bought the whole lot for an undisclosed price.

Many Alamo collectors are like UFO enthusiasts: they desperately want to believe in their stories, and they’re not shy about tearing down anyone who casts doubt.

Bruce Winders, the Alamo’s official historian and curator from 1996 to 2019, says that he has heard disquieting rumors about the items Guimarin and McDuffie sold to Collins. But, he notes, he and his colleagues among the Daughters of the Republic of Texas did business with Guimarin, and liked him. “He was a business partner for the Alamo at one point, and it just became one of those things where you didn’t ask questions.”

Still, when asked whether McDuffie’s name set off any warning bells, Winders acknowledged that his encounters with McDuffie’s work had troubled him. “Bells? All the bells. Yeah, kind of like Notre Dame. People are amazed at some of the artifacts he comes up with. How does he find so many choice artifacts?”

Though the majority of items in Collins’s collection—including all of the documents—appear to be authentic Texana, many serious Alamo collectors regarded certain items, including the flashiest ones supposedly connected to Bowie, Crockett, and Travis, with bemusement. According to the inventory included in the Deed of Gift to the Land Office, there are at least 35 large items—mostly cannonballs, weapons, soldiers’ possessions, and uniform items—that are directly tied to the battle. Then there are the dozens of small items from the History Shop dig, which are said to be Alamo artifacts. Many of these have come under scrutiny.

“No collection is totally devoid of at least a couple of items that are questionable, at the very least,” says Compton LaBauve, a prominent Louisiana collector who routinely buys and sells items from the time of the Texas Revolution. “But the Collins collection contains more questionable pieces, with more than questionable provenance, by far, than any collection I’m aware of.” McDuffie, in turn, claims that there’s bad blood between him and LaBauve, who he says has himself been mistaken about some artifacts’ authenticity. And at least one other prominent expert has acknowledged that it’s difficult to compare the Collins collection to other collections because of its scope and nature.

Many collectors’ puzzlement grew when Collins’s The Alamo and Beyond was published, in 2012. The gorgeously illustrated book is a source of profound skepticism in the Alamo collecting and archaeological worlds. “Just about everything they said was used at the Alamo—these are not Alamo-related items,” says Thomas Nuckols, who volunteers as an archaeological consultant to the Texas Historical Commission and is an expert on Alamo-era artifacts. “A lot of us enjoyed the book just because of the silliness of it.”

Two history professors from McMurry University, in Abilene, oversaw the book project. Even before meeting with Collins, though, they had concerns. “I was kind of in charge of quality control, and I knew that the provenance on some of these artifacts was, uh, well, not too solid,” recalls Stephen L. Hardin, who is probably best known for his 1994 book Texian Iliad. “I said, ‘You know, Phil, we can’t just say this is Davy Crockett’s shot pouch.’ It very well could be, but we asked a lot of tough questions. He was always very cooperative and very receptive. He doesn’t want to be embarrassed either. I can’t speak for Phil, but my sense is that he knew that some of the artifacts might not be the genuine article. But if he bought literally all of them, some would be. For a while he was buying literally everything that came on the market. To people who manufacture bogus artifacts, that’s a bird’s nest on the ground.”

Hardin believes the Collins collection has enormous cultural and historical value, but he urged Collins to couch his claims wherever possible. “If you go through the book carefully, you will see a lot of qualifiers,” he says. “That’s because we didn’t want this to come back and bite us in the ass. All we’re saying is, ‘This is the Phil Collins collection.’ Beyond that . . .” Here, Hardin’s voice trails off. “Beyond that, and with further research, let’s just say we have heard the same reservations that you have.”

These reservations were touched on in a 2012 Collins profile in Texas Monthly. Hardin told the writer, John Spong, that even if certain items couldn’t be definitively linked to Bowie, Travis, or Crockett, they still had value as period pieces. “Take the belt that supposedly held Travis’s sword,” Hardin said. “That’s really hard to prove. But it’s an 1830s sword belt from the Texas Revolution, and that’s significant.”

When Spong asked Collins about the belt, the easygoing manner the singer had consistently displayed vanished. “This is all bullshit,” Collins vented in an email. “Whoever described that to you has no idea of what went on and should mind their own business! I have as much provenance as you could hope for. In my book, I have a question mark in the title of the essay relating to the belt because its origin, like most Alamo artifacts, is hard to prove. Then if you do try to prove it, there are people lining up to shoot you down in flames.”

McDuffie and Guimarin echo these sentiments, arguing that they did enough research to make their claims by what might be referred to as “Alamo standards.” They say the Alamo is a special case and that it’s almost impossible to prove any item was present at the battle without some shadow of doubt. The site, after all, was looted after the fight ended and the various objects scattered to places unknown. Anyone who wants to claim that an antique was at the Alamo almost always has to take a leap of faith—a much lower standard than most museum pieces are held to.

Still, across the clubby world of antiquities dealers and collectors, Collins’s book was met with incredulity. “I’ve dug the sites, I know what weapons were used, and the artifacts Phil has just don’t fit,” says Nuckols. “He says he has cannonballs shot by the Twin Sisters at San Jacinto. Nobody knows what caliber those cannons were! He shows pictures of rusted metal and says these were shot out of Texas cannons. It’s just rusty metal! It could be literally anything.” (McDuffie says that the cannons’ caliber is known because it was cited in Sam Houston’s memoir. But Houston’s memoir is regarded by many as unreliable on this issue; the cannons’ caliber is widely debated among scholars of the period.)

What really incensed Nuckols, though, was the description of items from the History Shop dig. In one passage, Collins writes that given the array of equine artifacts they uncovered, “it seemed indisputable” they had found a campsite used by the Mexican cavalry commander Juan José Andrade.

“They found horseshoes,” Nuckols says. “Collins says they were from Santa Anna’s cavalry. In fact, we know that in the late eighteen-hundreds, there was a blacksmith shop on that site. Those artifacts could be from any time period.”

Mark D. Zalesky, the longtime editor of Knife Magazine, says he was floored by Collins’s claims for his knives, including the Bowie knife. “There are eight knives in the book, and one, the Sam Houston knife, is great,” Zalesky claims. Every other knife, he says, is either fake or lacking the proper documentation.

Zalesky, who has followed the Musso knife controversy for more than twenty years, is convinced that the knife is a fake. When Musso first began showing it in the late eighties, Zalesky says, “very quickly [some] experts reacted negatively and were sort of beaten back with threats of lawsuits from Joe. Many battles were fought over this during the nineties, in Maine Antique Digest, that sort of thing.” Over time, he says, knife experts and even the smaller subset of Bowie knife enthusiasts grew divided over the knife’s authenticity. “Musso finally found a community that accepted it—the Alamo community. And then he found a fellow who had a lot of money and wanted Jim Bowie’s knife.”

Zalesky believes the knife was probably made in England in the early 1970s, and he claims, “I have a photo of this [exact] knife in London in ’72, from the London Daily Telegraph, [held] by the girlfriend of a dealer who is a known associate of the most notorious Bowie knife counterfeiter of all, a man named Dickie Washer.” Zalesky also claims that one of Musso’s lab reports proves that the knife was not made from the steel that would have been used in the nineteenth century. (Other experts interpret the lab results differently, and Musso believes that the lab report proves that the knife was made from steel that would have been used in the nineteenth century.) Zalesky says that it would be painful for him to ever see the knife associated with Jim Bowie’s name at the Alamo. “It’s fake,” he insists.

He’s not the only one who thinks there’s some monkey business going on here. Hendershott says that he was stunned to see the New Mexico knife he sold to McDuffie attributed to Travis. He never saw the knife in person (he sold it on behalf of its owner), but he had published close-up, detailed photos of the knife that show no evidence of any engraving, nor of griminess. He claimed the initials “W B T” had been recently engraved in the knife guard. “It’s a fake!” he writes by email. “I’ve seen this a hundred times.”

In the opinion of the dozen or so experts and collectors we spoke with, the jewels of the Collins collection—at least eight items, none of them documents, that are said to have belonged to, or to possibly have belonged to, Bowie, Crockett, and Travis—are of questionable authenticity. When we asked Hardin, the history professor who oversaw the Collins book project, whether even one of these items has anything like solid provenance, he lowered his voice. “No,” he said. “No.”

Guimarin and McDuffie dismiss these criticisms as professional jealousy. “Every single enemy that I’ve made has been because they’ve valued their ego over the truth,” McDuffie says. He singles out Hendershott as someone who is trying to ruin him.

Since McDuffie and Guimarin claim the controversy is nothing more than bad blood within the community of Alamo historians and artifact-collectors—and that community is clearly one that is riven with intense competition and jealousies—we reached out to someone far outside that community: Henry Yallop, the keeper of armor and edged weapons at the United Kingdom’s Royal Armouries. He agreed to speak generally about the field but said that he could offer an opinion on a specific object only after viewing it, and then only to the legal owner, neither of which was possible in this situation.

Yallop, who said that he couldn’t comment on the customs of irregular forces, such as those that fought at the Alamo, explained that armies sometimes engraved a weapon number on an object for inventory purposes. Additional decorations sometimes denote that an object was used at a specific battle, to turn it into a presentation piece. Yallop also noted that in his experience, engravings can be somewhat obscured by dirt and grime, but that experts at the UK armories were “not aware of an instance where the application of gun oil and solvents made inscriptions magically appear.”

Yallop said he knew of no instance where an obscured engraving led to the attribution of a weapon to a famous warrior. “On its own, an object being of the right date and having relevant initials would not be considered as definitive ‘proof’ by most people,” Yallop wrote in an email. “In certain circumstances, this would enable further research to be done which could help build evidence.”

For centuries, people have altered historical objects to make them more valuable, Yallop added. “It should be noted that such engraving could have been added many years ago, but that does not necessarily mean they are from an object’s ‘working life,’ ” he wrote. “In the past people may have added engravings or other decoration to an object that was already thought / known to be associated with something. Or they could have been added with no such association, to deliberately deceive.”

No one appears to have communicated any of this skepticism to Jerry Patterson when he was negotiating with Collins. Nor did Patterson or anyone on his staff seek independent assessments of Collins’s artifacts before or after promising to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on a museum that would display them. Patterson and Collins repeatedly stated that one precondition of Collins’s donation is that “the entire collection” and the collection “in its totality” be displayed in one place. (The deed of gift that Patterson and Collins signed, though, seems to give the GLO total discretion over what items it displays and how it displays them. Patterson also says that by “entire collection” he was referring not to every item in the collection, but to what the GLO determines are the legitimate items in the collection.)

Winders, until recently the Alamo’s official historian, remembers that the collection arrived at the mission in October 2014, three months after Patterson and Collins made their public announcement. As he read through the four books of receipts of the items’ provenance that Collins furnished, he found himself feeling deeply concerned. “It was kind of painful because I was finding things that were somewhat disturbing,” he remembers. “What I saw were items that said they were of this type and that they could’ve been at the Alamo.” But again and again, Winders found no documentation placing them at the battle. “There’s enough to make you think that there is some deception going on here.”

Winders conveyed his concerns to the Alamo’s board and to Mark Lambert, the Land Office’s deputy director of archives and records. “I told our people that this is going to have to be addressed at some point,” he says. “Mark Lambert was concerned. He was kind of in the same position as I was when I talk to my management. [They were] always, ‘We’ll deal with that when the time comes.’ ”

Guimarin and McDuffie dismiss any such concerns. Guimarin says that Winders is “super conservative,” and McDuffie scoffs at the Land Office’s expertise. “The General Land Office doesn’t know their head from their ass with their stuff,” he says. “They don’t know what they’re looking at.” He says he provided Guimarin and Nesmith with detailed reports on each item, including photos showing how he revealed the inscriptions.

The “Cradle of Texas Liberty” hasn’t made a great impression on visitors. The average time spent inside Texas’s most visited historical site? About ten minutes.

The Land Office (which declined to answer any of our questions over a period of months) declared Collins’s receipt books confidential when we asked for them last summer, but after we appealed that decision, the Texas attorney general’s office made them available, redacting only the prices that Collins had paid. Nesmith signed most of the certificates of authenticity, and many of them are a master class in how to weave compelling tales with carefully hedged language.

Nesmith’s certificates begin with detailed professional descriptions of the objects, then launch into prosaic storytelling. He is particularly vague about certifying a shot pouch said to have belonged to Crockett, which Collins bought from Guimarin in 2009. In his write-up, Nesmith uses many passive sentences and avoids an explanation for his attribution. “The pouch appears to have a most interesting history and was recovered from the personal effects of Colonel José Enrique de la Peña. It is listed in an inventory of his property at the time of his death in 1840. It is also stated [in the probate document] that these items were given to Don José Enrique de la Peña, while serving at the Alamo during the war in Texas, by ‘D’ David Croquet in appreciation of de la Peña’s attempts to save his life,” Nesmith wrote.

Every Alamo-head is aware of the probate document, but how does Nesmith know this particular pouch is the one mentioned in the document, the pouch that belonged to Crockett? He never explains.

Nesmith and McDuffie offered a similarly fanciful certification of the knife said to belong to Travis. “Collectively, an unbiased conclusion can be drawn that the [lot] is true Texana material,” the certificate says. “More importantly, when considered as a whole, research into the clues left behind on each artifact suggests a common point of origin, a definite association with a specific individual within a very narrow historic window; the attribution is solid and beyond probability.” Nothing in the five-page certificate offers proof for any such claim.

Nesmith’s oddest testament, though, is reserved for the Musso Bowie knife. An essay accompanying the authentication document is titled “Sam’s Psychic Impressions on J B’s Knife.” In this performance Nesmith channels the story of a young Mexican soldier discovering a brass-back knife after the Battle of the Alamo and his sergeant confiscating it. The sergeant’s commander then takes it for himself. And so this tall tale goes on, until the knife ends up in California (which is where Musso bought it at a gun show). Another supposed authenticator, described as “a descendant of one of the martyrs of the Alamo and a forensics analyst,” offered what he called his “independent psychic impression.” He declared, “There is an incredibly overpowering sadness associated with the knife.”

Nesmith concludes in the authenticating documents, “It is most probably the knife carried by Bowie during his encounter with Comanche Indians at the Battle of Calf Creek, while searching for the Lost San Saba Mine. It is also the knife carried by Bowie during the Siege of the Alamo and probably the last object he held prior to his death.” No evidence is cited for any of this.

Looking through the documents, it becomes clear that what started in 2004 as a staid collection of early Texas documents took on a more speculative and fanciful cast as the years went by. Which makes for an uneasy fit with the real world of politicians, government agencies, and taxpayer dollars.

While the Alamo has long commanded a leading role in the story of Texas, much of the mission’s original footprint, which is bisected by city streets and encompasses tourist traps, has long been an afterthought. The historical exhibits inside the Alamo aren’t much better. The “Cradle of Texas Liberty” hasn’t made a great impression on visitors. The average time spent inside Texas’s most visited historical site? About ten minutes. The site is boring and gives tourists no sense of the Alamo’s original scale.

And what is shown inside the Alamo is, to put it gently, one-sided. Anecdotes abound of Mexican American students discovering on field trips that their forebears were the bad guys—and, eventually, the losers—in Texas’s creation myth. The Alamo has, over the years, become a story that white Texans retell and many Hispanic Texans, especially in San Antonio, ignore or resent. Historical findings of the last few decades that challenged the traditional narrative—most notably evidence that Davy Crockett did not go down swinging, as was portrayed by Fess Parker, but instead begged that he be spared—are considered taboo by many. And evidence that some of the Alamo defenders were motivated by their desire to retain ownership of their slaves rather than be subject to Mexico’s prohibition of the practice is regarded by many Alamo traditionalists, including many elected officials, as incendiary. Yet the need to tell a more accurate, inclusive story of the Alamo, especially given that the site is located in the middle of the country’s largest majority-Hispanic city, seems undeniable.

Attempts to revitalize the Alamo began in the seventies, yet they always failed, for predictable reasons. The state owned the Alamo but in 1905 gave control of the site to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, a group then made up of women who could trace their lineage back to those who “rendered loyal service to Texas” before it became a U.S. state. Neither the state nor the city had ever shown a lot of interest in funding adequate repairs of the Alamo, much less a full-scale restoration. In 1994 San Antonio mayor Nelson Wolff formed the Alamo Plaza Study Committee, which recommended telling a more historically candid story and closing the streets that ran through the site. Without state funding for the project, though, the committee’s report went onto a shelf, where it would sit for two decades.

But slowly, there was movement. In 2011 the Texas Legislature, tired of the DRT’s mismanagement and inertia, gave the Land Office oversight of the Alamo. Then, three years later, Mayor Julián Castro took the study committee’s report off the shelf and handed it to a new group called the Alamo Plaza Advisory Committee. That body, unlike its predecessor, included representatives from state government, which was key for any progress. Because the city owns Alamo Plaza and the state owns the Alamo, the chapel, and the Long Barrack, a restoration of the entire site requires that the city and state cooperate.

The 2014 report recommended that the site tell the story of the centuries-long sweep of the Alamo’s existence. And it proposed doing so in a history museum that would take longer than ten minutes to breeze through. It also recommended closing the streets in front of the Alamo and moving the Cenotaph, which badly needed repairs, outside the walls of the Alamo. The sixty-foot-tall monument to the Texans who fell at the battle is a twentieth-century creation; its relatively recent vintage, it was felt, violated the historical integrity of the fort.

That’s where George P. Bush entered the picture. He moved into Texas politics at flank speed, winning a 2014 statewide election in his first bid for public office. His timing was opportune. Following Mitt Romney’s loss to Barack Obama in 2012, the GOP convinced itself that it needed to reach out to Hispanic voters, and a photogenic, Spanish-speaking, half-Mexican heir to the party’s greatest political dynasty must have looked like the man for the job.

When he assumed the land commissioner job in 2015, Bush was on board with the master plan produced by Castro’s citizens’ committee. Bush, a former high school history teacher, was even on board with the city’s requirement, in its lease with the state, that the site not focus solely on the thirteen famous days in 1836 and instead teach the warts-and-all, three-hundred-year-long history of the site. “The Alamo can be a centerpiece for taking on the controversial issues of the past,” he said at the same Texas Tribune Festival panel that Collins appeared on, specifically mentioning slavery, Mexican control of Texas, and Spanish colonization.

This was in late September 2016, when nearly everyone believed that Donald Trump’s coarse pluto-populism, including his invective against Hispanic migrants, was going to doom him to defeat in the presidential race. The GOP’s elite was still committed to a multicultural future for the party, and Bush was all in with that vision. In 2015 he toured Gettysburg National Military Park, in Pennsylvania, to get a sense of how to create a historical site that balanced fact and legend. San Antonio City Council member Roberto Treviño, who cochaired the Alamo Plaza Advisory Committee, joined him for the trip, and came away convinced of Bush’s sincerity. “I had the impression all of us on the trip had the same vision for the Alamo,” Treviño says.

In 2017 the Alamo Trust, a nonprofit that the Land Office created in 2011 to run the Alamo, released an early design concept for discussion. The renderings included a four-story museum across from the chapel and Long Barrack. The Cenotaph was shown in a new location off Alamo Plaza. But what drew most of the criticism were the glass walls that would encircle the plaza. Long a gathering place for protesters, tourists, and locals waiting to catch a bus, the plaza would be closed to members of the public unless they had paid to enter. Many San Antonians felt the wall’s construction was a seizure of a community space. Alamo traditionalists thought an entry fee commercialized a holy site.

Nonetheless, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, who keeps a scale model of the Alamo and memorabilia from the John Wayne movie in his office, pushed the Legislature to provide another $75 million for the Alamo project in 2017 on top of $31.5 million that had been appropriated in 2015 for repairs to the chapel and Long Barrack and the purchase of the buildings across the plaza that now house tourist sideshows such as Louis Tussaud’s Waxworks and Ripley’s Believe It or Not! The city had already kicked in $38 million for street repairs.

The remainder of the estimated $450 million price tag—roughly $300 million—would go toward building a four-story, 130,000-square-foot museum to house a number of items, most prominently the “Phil Collins Texana Collection.” A lease agreement Bush signed with the city in 2018 put the state on the hook for the museum and the restoration of the plaza. To raise the funds, Bush called on the “Texas Titans” he had recruited to help with the Alamo in 2015: heiress and philanthropist Ramona Bass, businessman B. J. “Red” McCombs, former Rackspace president Lew Moorman, and developer Gene Powell. Specifically mentioned in the lease was a requirement that the development adhere to the plans from the Castro-appointed Alamo Plaza Advisory Committee, which meant moving the Cenotaph off the original footprint of the Alamo to create a more historically accurate visitor experience. At the time, that didn’t seem like a big deal. Everyone seemed to be on the same page, and the Alamo’s—and George P. Bush’s—future looked bright.

Soon, though, cracks began to form in the consensus. In 2018 someone leaked an internal audit critical of the lack of transparency created by the public-private structure of the Alamo’s management. Bush blamed Patterson loyalists for the leak and cleaned house, creating a supply of angry insiders eager to gossip about what they regarded as Bush’s excessive penchant for secrecy and his team’s focus on promoting his political interests. (“He was completely paranoid,” said one such insider. “He was probably one of the more cowardly politicians I’ve ever worked for. He was like a new car that nobody wants to get a ding on.”)

Bush had also fired the Daughters of the Republic of Texas as caretakers of the Alamo for committing a number of contractual violations. This was arguably the right move, but it was poorly handled; the DRT members learned of their firing from news reports, which gave them good reason to complain that they had been treated shabbily. And when the Land Office changed the locks on the DRT’s library, the pugilistic doyennes sued for control of the library’s holdings—and won.

But the issue that really brought the situation to a boil was the plan to remove the Cenotaph for repairs and then relocate it just outside the footprint of the Alamo fort.

This move had drawn little complaint earlier. But in 2017 the world had changed. The violent “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in May spurred many across the country to engage in a reckoning with America’s racist past. Statues of Confederate soldiers were removed from cities all over the U.S. In September, San Antonio removed a Confederate statue in Travis Park—without public notice, in the middle of the night—and sent it to an undisclosed location, ostensibly for repairs. That clandestine removal set off alarms among the state’s more militant Alamo traditionalists, who were now convinced that the plan to repair the Cenotaph was a lie, and that Bush planned to stick it in storage somewhere.

In October 2017, protesters gathered at the Cenotaph to push back against the plans, and the demonstration morphed into an anti-Bush event. “Go back to Florida and save the manatees,” Lee Spencer White, one of the founders of a group called the Alamo Defenders Descendants Association, said of Bush. “We’ll take care of the Alamo.” “Vote George P. Santa Anna Bush out of office,” said another protester, to applause. The protest drew statewide news coverage, and Jerry Patterson, who attended, decided to try to get his old job back. He ran a campaign so focused on Bush’s management of the Alamo that the chapel’s roofline served as his campaign logo.

Bush had no choice but to fight the Alamo fight, even if only by proxy. He assigned an aide named Bryan Preston to be his Mr. Alamo, and that winter Preston was everywhere, on radio shows and at luncheons, gently explaining that “reimagining” the Alamo simply meant updating the site, getting rid of the vehicle traffic and the lurid tourist attractions, and turning it into a world-class venue Texans could be proud of. The Land Office ran explanatory Alamo ads on the radio across Texas and started a Facebook page called “Save the Alamo.”

“We are Texans doing a Texan thing,” Preston explained. The Alamo is “our superhero origin story, and it happens to be true.”

With the heat rising on his right, Bush began distancing himself from the master plan’s call for the telling of a more complete and accurate story of the Alamo’s history. Gone, by and large, were references to slavery and Native Americans. Back in the saddle was the heroic Anglo narrative that Bush had promised would be put in context. Every Bush appearance was peppered with references to 1836. “We must restore the battlefield to honor the Alamo’s gallant defenders,” he said at a press conference on the plaza just a week after the Cenotaph protest. “We must respect this sacred space. We must and will ensure that 1836 lives here every single day.”

But Bush’s betrayal of the revisionists failed to calm traditionalists. And his defeat of Patterson (and a descendant of Davy Crockett who also ran) in the GOP primary didn’t settle things, either. Ray Myers, a tea party leader and member of the State Republican Executive Committee, won passage of a GOP resolution decrying the “forces at work to remake or ‘Reimagine’ the history of the Alamo and diminish its inspiring message while the property around it undergoes renovation to increase profit from tourism.” In his address to the Texas Republican Party convention during the summer of 2018, Bush blamed criticism of his Alamo stewardship on “fake news” in the “liberal media” and was met with loud boos. Dozens began shouting, “Remember the Alamo!” Bush spread his arms wide, grinned, and then shrugged: “I did win, right?”

What Bush didn’t emphasize in any of his public comments was that legally he was bound to adhere to the Alamo Master Plan required by the lease he had signed with the city. And that plan called for a historical retelling that focused less on the siege and included more about the Spanish colonizers, the Indigenous peoples, and the Tejano culture that long predated the arrival of the Texians. Bush may have won an election, but that didn’t mean he could do whatever he wanted. He had to be careful about what he promised.

Bush had reason for caution when it came to moving the Cenotaph. Though the state’s lease required its relocation, Republican lawmakers in Austin were adopting an official “come and take it” policy. In May 2019 the Texas Senate amended a bill preventing the alteration, removal, or relocation of Confederate monuments to include the Cenotaph. The Senate adopted the amendment on a party-line vote, though the bill didn’t pass the House.

Bush’s instinctive caution was finally cast aside a year after he won reelection. Rick Range, a retired firefighter who had run against Bush in the GOP primary in 2018, had long been a pest. For months, Range had been making baseless accusations, such as claiming that Bush had proposed renaming the Alamo the Misión San Antonio de Valero. And for months, Bush had studiously ignored Range’s provocations. But when Range posted on Facebook on December 10, 2019, that Bush planned to erect a statue of Santa Anna at the Alamo, Bush finally got out of his defensive crouch and onto Twitter.

“One must ask themselves, why am I being accused of honoring the murderous dictator Santa Anna? Is it because my mother (now a naturalized citizen) is from Mexico?” he tweeted. “I was born in Houston, my wife is from San Angelo, and my boys were born—you guessed it—here in Texas . . . The idea that I would EVER place a statue of Santa Anna at the Alamo is patently false. Enough is enough. This is an outright lie, and is quite frankly, flat out racist.”

The tweet caught Dan Patrick’s attention. The lieutenant governor had been a supporter of Bush’s Alamo plans and had given no indication that he opposed them. But right around this time, as he began hearing rumors that Bush was interested in his job, he turned on a dime.

Patrick seized on Bush’s tweet and twisted his words beyond recognition. In a public statement on December 18, he claimed that because of the Senate vote to put the brakes on the Cenotaph’s relocation, Bush’s tweet essentially accused every state senator of being a liar and a bigot. “The 31 members of the Texas Senate represent over 28 million Texans. They are not a vocal minority—nor are they liars or racists,” Patrick wrote. This was false on two levels. First, only 19 senators voted for the bill. Second, Bush’s tweet was not, as Patrick insinuated, an attack on anyone who took issue with the redevelopment of the Alamo; it was an attack on one man, Rick Range, who had been making false statements.

But Patrick, as is his habit, wasn’t about to let the facts get in the way of score-settling. On March 5, 2020—the eve of the battle’s anniversary—Patrick complained that the “design, planning, and execution of the project is badly off track.” Behind the scenes, Patrick was playing hardball. He reportedly told John Nau III, the longtime chairman of the Texas Historical Commission, that if he didn’t reject the plans to relocate the Cenotaph, his commission’s budget would take a haircut in the next legislative session. “It was all about ‘I’ve got to do this for the lieutenant governor,’ ” the Alamo advisory committee’s Roberto Treviño recalls Nau telling him at the time. (Nau did not respond to requests for comment.) In September the THC rejected the application to move the Cenotaph.

Patrick’s feud with Bush had escalated throughout the year. In June, after someone spray-painted anti–white supremacy graffiti on the Cenotaph and Black Lives Matter protesters marched on the Alamo, Bush went on Fox & Friends to “send a very clear message that you don’t mess with Texas and you don’t mess with the Alamo.” Hours later, Patrick tweeted, “Nobody has put the @OfficialAlamo at more risk than @georgepbush with the outrageous ‘reimagining’ plan, lousy management, lack of transparency and moving the Cenotaph.” In October, Patrick publicly called for an audit of the project.

The city-state-philanthropic coalition that had united around a vision of teaching the whole history of the Alamo fell apart. That fall, Alamo CEO Douglass McDonald, who supported moving the Cenotaph, stepped down after announcing that he didn’t want his contract renewed. “People would rather fight about the Alamo than fight for the Alamo,” he said privately. Gene Powell and Ramona Bass walked away as well. “All of a sudden,” Powell says, “after years of agreement on telling the story of all the layers of history of the site, everyone now seems to want this to be John Wayne’s Alamo.”

As Bush struggled with political opposition to his Alamo plans, he started feeling pressure from another party. “I have to admit I’m getting more than a little discouraged with the speed and urgency that is being displayed regarding my collection and related museum. Please update me with a likely museum date,” Phil Collins wrote Bush aide Hector Valle on May 25, 2020. “I don’t want my collection sitting in boxes in a basement. This is the situation now it seems. I realize there are more pressing things on P’s list, but on my list, my hard-earned collection is important to me. Please let me know the situation . . . the REAL situation.” Valle did not respond to Collins, at least not in writing.

By coincidence, a few weeks later, on June 14, McDuffie asked Collins via email if he would answer our questions about the sketchy authentication of his collection. This seems to have further angered him. “I would like you to consider the real probability of me withdrawing my collection and giving it back to me,” Collins wrote to Valle on June 15. “I’ll be happy to donate it when the museum is ready, but right now, I’d like to bring it back. I don’t want to bring lawyers in, but I will if need be. Plus I’m getting flack on what’s ‘real’ and what’s not. Please let me know.”

The Bush team scrambled. “Please know that your collection is extremely important to the entire State of Texas and we would not be where we are in this process if not for you and your generosity,” Valle replied. “You sparked this entire Alamo Plan and we owe you so much.”

A week later, apparently after a phone call, Valle offered to put part of the Collins collection on display as soon as possible if he didn’t want to wait for the museum. He also promised a phone call with Bush, but Collins would prove too busy, canceling four calls, each at the last minute. When we asked Collins again for comment, he declined, via email. “Life is busy at the moment, with music rehearsals and personal stuff, so I’ll have to pass on your request,” Collins wrote. “Of course I’m totally interested but I cannot deal with this right now.”

By the end of 2020, Collins’s museum seemed further away from being built than it was at the beginning of 2020. But providence came in the form of a succession of scandals befalling Attorney General Ken Paxton, who has been under indictment for alleged securities fraud since 2015 and had recently become the subject of a separate FBI investigation involving bribery allegations. Bush, sensing an opportunity, became interested in launching a 2022 primary challenge against Paxton—which reassured Patrick that Bush was no longer his rival. Suddenly the two men were on the same page once again. On March 1, the day before Texas Independence Day, Bush testified before the Texas Senate that he and Patrick had achieved what the combatants of the Battle of the Alamo could not: a truce. “He’s fully on board,” Bush said of the lieutenant governor.

“Importantly, we agree that the issue of the Cenotaph is resolved, and the monument will not be moved,” Patrick said later that day. “We further agree that the story of the 1836 Battle of the Alamo must be the central focus on any master plan design.”

The very same day that an accord was reached in Austin, San Antonio mayor Ron Nirenberg got his hatchet out, removing councilman Treviño from the Alamo Management Committee and the Alamo Citizens Advisory Committee, both of which he chaired. Treviño’s sin, said Nirenberg, was refusing to accommodate the Land Office’s insistence on keeping the Cenotaph where it was. By this time, nearly everyone who first joined hands around the revisionist Alamo Master Plan had long since been alienated, and the years-long effort to create a more historically accurate experience at the Alamo had become “politicized and compromised,” Treviño says. “Exactly what we have been trying to avoid the whole time.”

Also on that day, Collins got part of what he wanted when the Alamo Trust opened an exhibit with five items from his collection that offers visitors a chance “to glimpse a selection of priceless artifacts graciously gifted to the state of Texas by musician and historian Phil Collins,” according to the press release. The exhibit does not include any of the controversial, big-name items.

Like Michael Corleone taking care of family business, Bush had neutralized many of the people who stood in the way of his political future. To his right, he had made peace with his archnemesis, Patrick. To his left, Treviño had been unseated from his positions of influence over the Alamo plans. (In April the San Antonio City Council approved a new lease with the Land Office that would leave the Cenotaph right where it’s been all along.) And, somewhere in between those two poles, Bush had mollified an irritable Phil Collins. Not bad for a guy who’s not known as a political brawler.

Many are now optimistic that a major Alamo revamp could go forward. Kaye Tucker, who initiated the deal with Collins all those years ago over dinner at El Mirador before leaving the Land Office in 2015, had long despaired that the museum would never come to fruition. “But now it looks like they’re moving in the right direction,” she recently said.

But Bush, unless he is extraordinarily lucky, may have merely pushed his reckoning to a later date. “He wants [the Alamo renovation] to be a feather in his cap,” says Hardin, the Alamo scholar. “Everyone knows this is a stepping-stone job for him. He wants to be president someday; he wants to prolong the family dynasty.” To get himself back on that path, though, Bush has had to capitulate to a nativist right wing that he had once set himself in opposition to (and, even so, the Alamo traditionalists still don’t trust him). The George P. Bush who could sell himself as the architect of a kinder, gentler, and more racially inclusive GOP has become less tenable.

And then there’s the museum that will house Phil Collins’s collection. In one sense, the museum could tie everything together. It could keep Collins happy, keep his artifacts at the Alamo, and satisfy the traditionalists who would love the emphasis on martial history. It would make Bush look like a mover and shaker who gets things done. And if the curation is handled with an eye to contemporary historical findings, perhaps even the activists demanding a more inclusive version of the Alamo story will feel heard.

But now, the plans to build the museum will have to be financed without philanthropic support because fund-raisers such as Powell were disgusted by political interference. In September, Patrick announced that the state would pay for the whole thing, meaning Texas taxpayers will be on the hook for the $300 million. (Neither Patrick nor anyone else in the Legislature submitted a bill calling for such funding during the 2021 session. To meet its obligation to Collins to break ground on a museum by this October, Bush recently announced that the Land Office would begin construction this summer of a 24,000-square-foot building on the eastern corner of the Alamo grounds that would, among other things, exhibit a significant portion of the collection until the state raises money for the larger structure.)

The success of this big-ticket project may depend on no one making a stink about the fact that the Collins collection might not be what it’s cracked up to be. And so far, the major players are staying mum. “Bush will never publicly admit it,” Hardin says. “He will never allow anyone in the Land Office to admit that they accepted the donation of a pig in the poke.” (Hardin, who maintains a relationship with Collins, later clarified that he was not referring to the entire collection as a pig in the poke but rather expressing his concern that the Land Office has not done due diligence.)

Perhaps Bush will get away with it; perhaps he’ll manage to challenge Ken Paxton for the top legal job in the state, prevail in the primary and the general, and then slide into office in January of 2023 and let his successor at the Land Office deal with whatever controversies erupt.

And they almost certainly will. If the museum opens, Texans may not be happy to learn that the state has spent hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars on a collection that includes items that the Land Office knew some experts regarded as suspect. Bruce Winders, the Alamo’s official historian, who was forced out in 2019, says that he and Mark Lambert, the Land Office’s deputy director of archives and records, gave their colleagues plenty of warning that they may be walking into the middle of a long-simmering melee fought by partisans who have no intention of backing down. “I don’t think the Land Office is prepared for the ruckus the collecting world is going to raise once the collection is made public,” he says.

This Battle of the Alamo, it seems, is far from over.

Chris Tomlinson is the business columnist at the Houston Chronicle and the San Antonio Express-News and the author of Tomlinson Hill. Austin writer Jason Stanford works in communications for a local school district and is the host of The Experiment, a Substack newsletter. Temple-raised Vanity Fair correspondent Bryan Burrough lives in Austin and is the author of six books of nonfiction.

This article originally appeared in the June 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Next Battle of the Alamo!” Subscribe today.

This story has been edited, since we first published it last month, to correct and clarify issues of accuracy and context raised by three of the people about whom we wrote.

• Alex McDuffie says that he did not own a web development business, as was reported, but instead worked as an employee of such a business.

• Alfred Van Fossen did not live in San Antonio, as was reported, but in the Houston area.

• The correspondence between McDuffie and Phil Collins took place not via text, as was reported, but rather via email.

• The excerpt stated that Van Fossen was notorious for selling questionable items supposedly associated with the Alamo. While Van Fossen had a reputation for selling questionable items, McDuffie says Van Fossen was better known for selling items from the Confederacy.

• The excerpt stated that “according to rumors circulating among knife collectors, [Jim] Guimarin and McDuffie arranged for Collins to buy the knife [purportedly owned by Jim Bowie] for $1.5 million.” McDuffie and Joseph Musso, the knife’s seller, both state that that figure is incorrect but have declined to provide an accurate figure.

• The excerpt stated that McDuffie took his purported Bowie sword to a metallurgist who determined that the blade was from the appropriate era. McDuffie has asked us to note that the metallurgist also stated that the inscription “J. Bowie” was covered with score marks and that those marks were left when the saber was pulled from its scabbard, “which indicated that the name was inscribed before usage.” (The excerpt did not include that information because the authors believe that the metallurgist’s examination was improperly conducted.)

• The excerpt quoted Thomas Nuckols, a volunteer archaeologist with the Texas Historical Commission, as saying that Collins claims “he has cannonballs shot by the Twin Sisters at San Jacinto. Nobody knows what caliber those cannons were!” McDuffie says that the cannons’ caliber is known because it was cited in Sam Houston’s memoir. (The excerpt did not include that information because Houston’s memoir is regarded by many as unreliable on this issue and because the cannons’ caliber is widely debated among scholars of the period.)

• The excerpt stated that Mark Zalesky, the longtime editor of Knife Magazine, claimed “that one of [Joseph] Musso’s lab reports proves that the [purported Bowie] knife was not made from the steel that would have been used in the nineteenth century. (Other experts interpret the lab results differently.)” Musso has asked us to make clear that he believes that the lab report proves that the knife was made from steel that would have been used in the nineteenth century.

•The excerpt stated that the General Land Office had agreed “to display [Phil Collins’s collection of Alamo antiques] in its entirety without authenticating every item” and that the GLO “promis[ed] to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on a museum that would display every single one of them.” Former GLO commissioner Jerry Patterson says that the authors’ assertions in their book and in our excerpt are false. He notes that the Deed of Gift that the GLO signed with Collins allows the GLO wide discretion on how it handles the Collins collection, including what will be exhibited. Texas Monthly was not aware of the discretionary powers language in the deed until Patterson brought it to our attention. The online version of our excerpt now includes a reference to the Deed of Gift.

• Our excerpt’s statement that the GLO was obliged to display the collection in its entirety was based on several pieces of evidence: At the 2014 press conference where Collins and Patterson announced plans for the collection, Collins stated, “One of the main reasons that I said yes to the Alamo … was that I felt that I wanted the entire collection on show” and “One of my criteria was that the collection should be on show, in total.” Patterson also told Stanford, “[Phil] had some conditions. The collection had to be in its totality, displaying at the same time.” Later, while we were editing and fact-checking the excerpt, associate editor Paul Knight read this verbatim passage from the piece to Patterson: “During their conversation, Collins told Patterson that he expected everything to be displayed in one place.” Patterson told Knight that that sentence was accurate. Patterson has since stated that when he and Collins referred to “the entire collection” and “the collection . . . in total” and “the collection . . . in its totality,” they were referring not to the entirety of the collection as it now stands, but rather the collection as the GLO chooses to define it. Items that are determined to be fake, for instance, might no longer be considered part of the collection. The story has been updated to reflect all of these statements, so readers can reach their own conclusions about what Patterson and the GLO promised to Collins.

The intent of our excerpt was to report on the controversy among those who have studied Alamo antiquities, regarding the authenticity of key items in Phil Collins’s collection. The purpose was to present multiple sides of the argument, not to take a side in the controversy. The authors of the piece stand by their reporting and suggest that those who are interested in exploring this subject further read their book Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Longreads

- George P. Bush

- San Antonio