I was flying blind. Nothing in my experience gave me a frame of reference for this journey. My son Mark was dying of acute leukemia, and the two of us were racing across the margins of the Chihuahuan Desert east of Van Horn, searching for the new top leaves of the creosote bush, which when brewed into a tea were considered a cure for the disease by some Mexican curanderos. I had learned this in a letter from a man who was doing twenty years on a drug charge in federal prison. I have received hundreds of letters from people in prison, but they always wanted something from me. This guy just wanted to do me a favor. Mark and I both knew that it was the longest of long shots, but long shots were all we had.

The trip was in early March, about six weeks before Mark died. It was long and arduous, and it sapped what little strength he had left. The letter had explained that the two of us had to leave a “gift of water” for the creosote plants. We flew from Austin to Dallas to Midland, then drove 125 miles to an isolated place within sight of the Davis Mountains, two liter bottles of Evian in the seat between us. Mark slept almost all the way, racked with fever, chills, and nausea. After collecting three bags of leaves, we spent the night in a Midland motel, the kid so sick that I wondered if he’d make it through the night. I was awake until two in the morning, talking long distance to friends and family, trying to figure out our next move.

Mark’s condition was diagnosed in July 1996 at a cancer clinic in Atlanta, Georgia, the city where he grew up after his mother and I divorced and where he had lived since his own divorce in early ’94. He had undergone six intensive doses of chemotherapy, whose powerful toxins destroy cancer cells—and good cells as well. I suspect that one day we’ll look back at this wretched procedure the way we look back with revulsion at frontal lobotomies. But chemotherapy was the only treatment available for Mark’s type of leukemia. It wouldn’t cure him, but it could possibly put the cancer into remission long enough for doctors to perform a bone marrow transplant.

We had searched without success for a bone marrow donor for nine months. Unfortunately, no one in our family was a match, and neither were any of the 2.7 million people on the National Bone Marrow Registry. Among Caucasians, a match exists for a given patient about 80 percent of the time; among minorities, the figure drops to about 50 percent. One doctor speculated that finding a match for Mark was so difficult because there are traces of Native American blood in our family, but he was just guessing. Anecdotal evidence suggests that genetic tissue typing for bone marrow produces unexpected results. In 1993 Anne Connally, the daughter-in-law of John Connally, turned out to be the world’s only perfect match for a sixteen-year-old Japanese girl, who is alive and doing well today because Mrs. Connally was tested and added to the national registry in 1990.

In January and February of this year, Mark’s family and friends had staged testing drives in Atlanta, Little Rock, and Austin, adding another 1,500 people to the national registery, yet still there was no perfect match. We were desperate. Even as we slept, even as we prayed, the clock was ticking. After my wife, Phyllis, and I ran a full-page ad in Texas Monthly pleading for help, people called from all over the country, volunteering to be tested, extending their support, and contributing money to the Leukemia Society of America. Rosalind Wright, a sister of Austin writer Lawrence Wright, telephoned from Lexington, Massachusetts, where she had rallied thirteen tribes of Native Americans and personnel from a military base to get tested. A friend in California who is a Buddhist monk sent a seed blessed by the Dalai Lama with instructions on how Mark was to ingest it. The pilgrimage to the desert was only one in a series of things we tried.

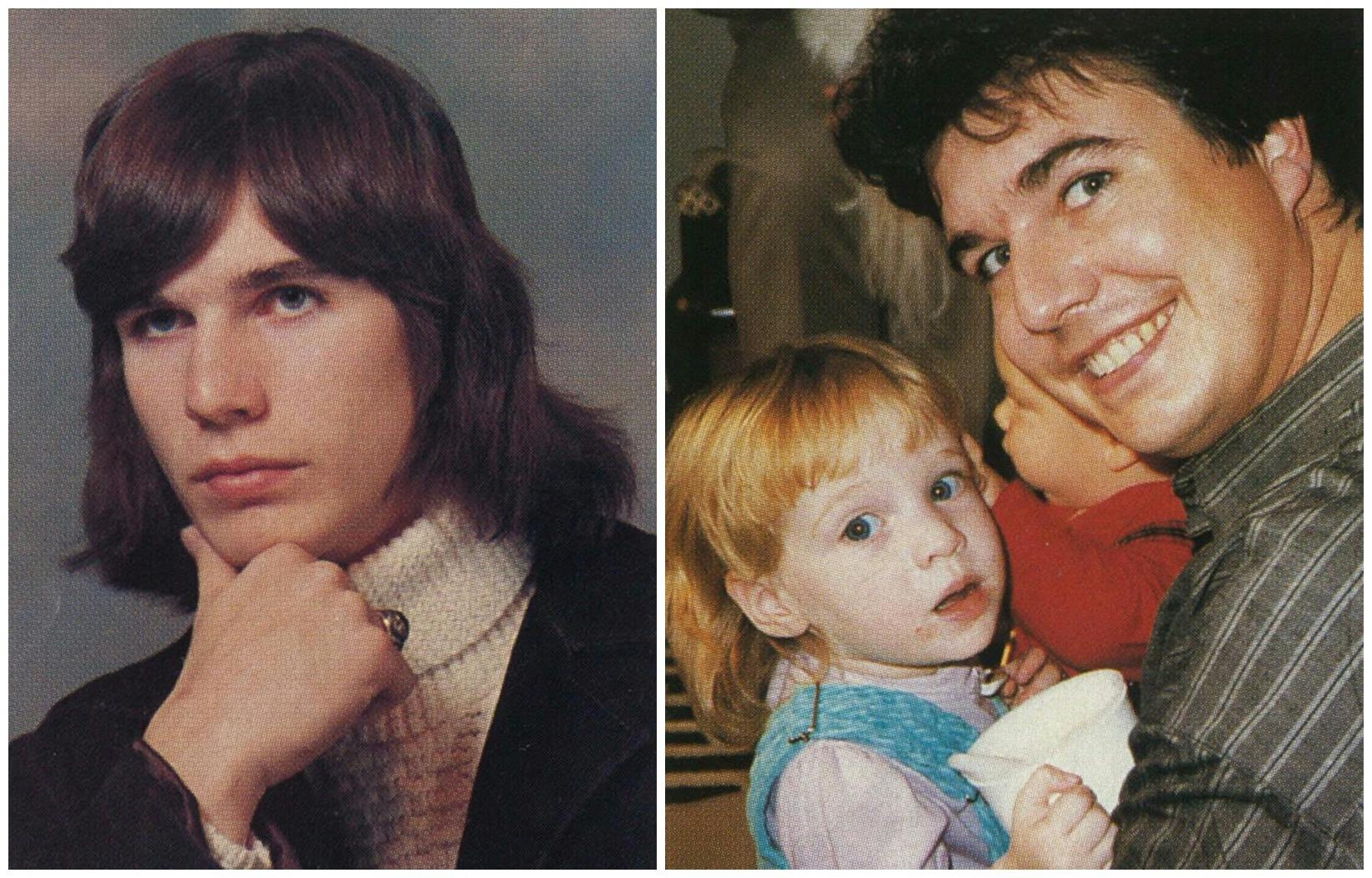

The worst day of my life—worse even than the day Mark died—started early the next morning, when I drove Mark to Midland International Airport for a flight back to Atlanta. Until then I hadn’t realized how far the disease had progressed. He was so weak that I doubt he could have walked unassisted to the gate. I helped him into a wheelchair and pushed him. He had eaten almost nothing for a week, so we stopped at the coffee bar; I bought him a Coke and a banana, and he was able to keep them down. For two days he had said almost nothing. A question that needed a response got a nod or a shake of the head. Looking at him then, as pale and weak as a newborn puppy, I couldn’t help but remember that a year before, Mark and I had worked out together at my gym in Austin, both of us fit and seemingly invincible. As recently as Christmas 1996 he had looked reasonably strong and cheerful. But now you could almost see his life leaking away.

When it was time for him to board the plane, we hugged and kissed, knowing it might be our final good-bye. I was close to tears. Watching my son shuffle slowly down the ramp to his plane, his hairless head bowed in agony, his clothes hanging off his emaciated frame, a kid who had just turned forty but looked ninety, I kept thinking: Why him? Why not me? When a child dies, “Why?” is the last question to go away.

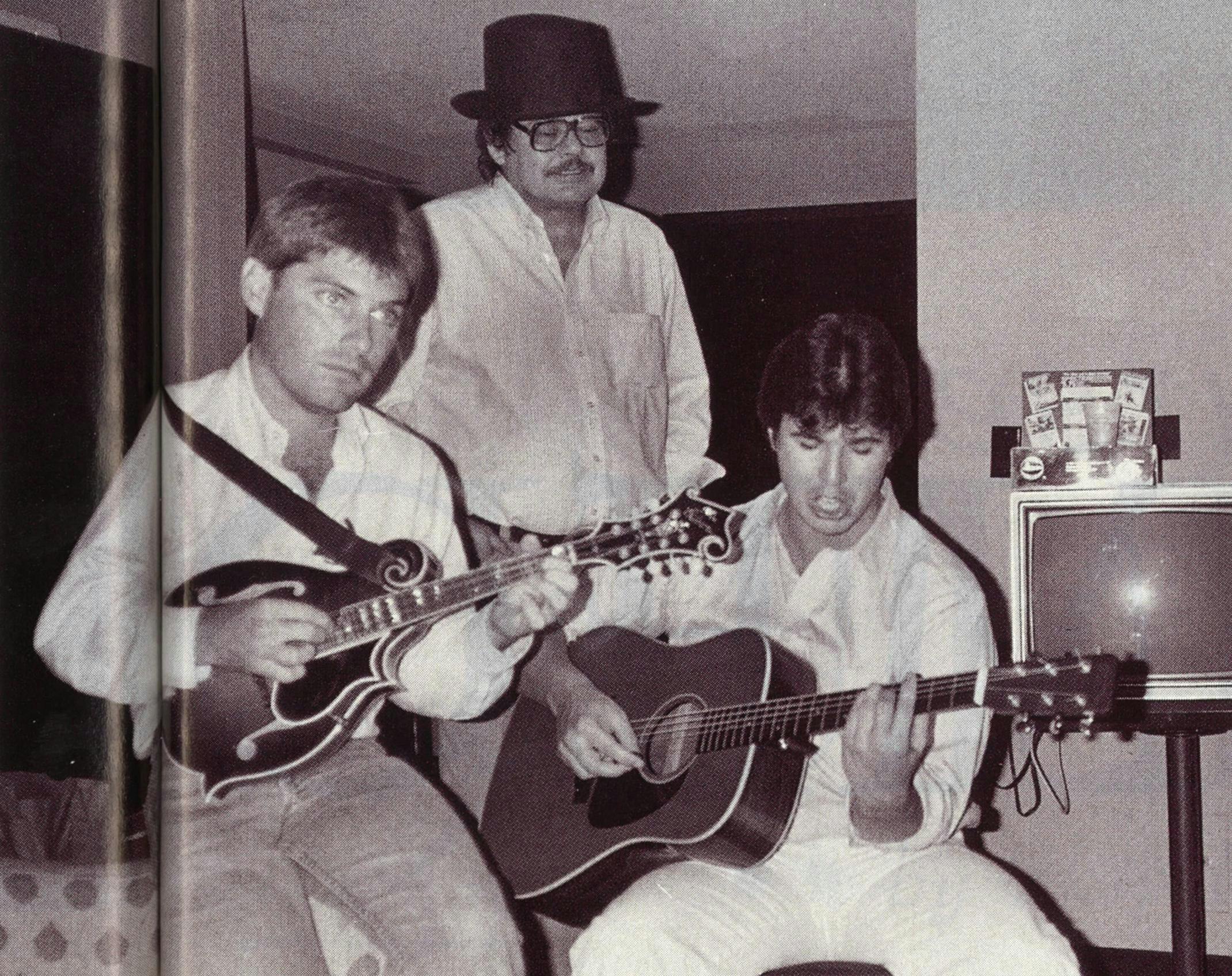

DURING OUR YEARS TOGETHER, we said a lot of good-byes, Markie and me, but one in particular sticks in my mind. He must have been around ten—a bright, resourceful, resilient, uncommonly stubborn kid—and he was dogging me to take him along on a business trip to New York. I explained that I didn’t have time to show him the sights, but he wanted to tag along, and I couldn’t say no. Our first night in the Big Apple, in a hurry to make an appointment, I gave him $20 and a key to the apartment where we were staying, then dropped him off in Times Square. I remember asking him, “Will you be okay?” His cocksure reply was, “Sure. Nothing to it!”

My cab hadn’t gone half a block when the stupidity of what I’d done slapped me upside the head: I’d deposited my ten-year-old son in the geographical center of the evilest, most sinister square mile in America. I threw open the door and raced back into oncoming traffic, but by then he’d been swallowed up in the crowd. For the next few hours, I was nearly sick with fear, imagining what might have happened. But when I got back to the apartment, there was Markie propped up on the king-size bed, a cat on his lap, eating a bowl of ice cream and watching a John Wayne movie. “Are you okay?” I asked, badly shaken. “Sure,” he said, grinning at me as though we were co-conspirators in a plot to overthrow the world. “Nothing to it!”

Because he grew up a thousand miles from where I lived, I saw him only a few times a year until he completed high school, in May 1975. A week after that he moved to Austin to attend the University of Texas, and for the first year, he slept in my large walk-in closet. I wasn’t married at the time, so we hung out together, shopping, cooking, eating, listening to music, having adventures. My dad had passed on to me an appreciation for cooking and eating, and I handed it down to Mark. Before long he was cooking gourmet meals that took three days to prepare and five hours to eat. I nicknamed him Maurice. Later, after he married Helen and moved into the professional world, Maurice’s seated dinners became legendary in Dallas and Little Rock. Journalists and politicians (among them Bill and Hillary Clinton) jockeyed for invitations. For one of my birthdays he whipped up a five-course dinner that included rack of lamb, dove breasts wrapped in bacon and sautéed in wine sauce, roasted ancho peppers with salmon and goat cheese, and an unbelievable dome-shaped dessert with layers of crushed Heath Bars, fudge cake, ice cream, and toasted butterscotch crust. Naturally, Maurice had selected the appropriate wine for each course.

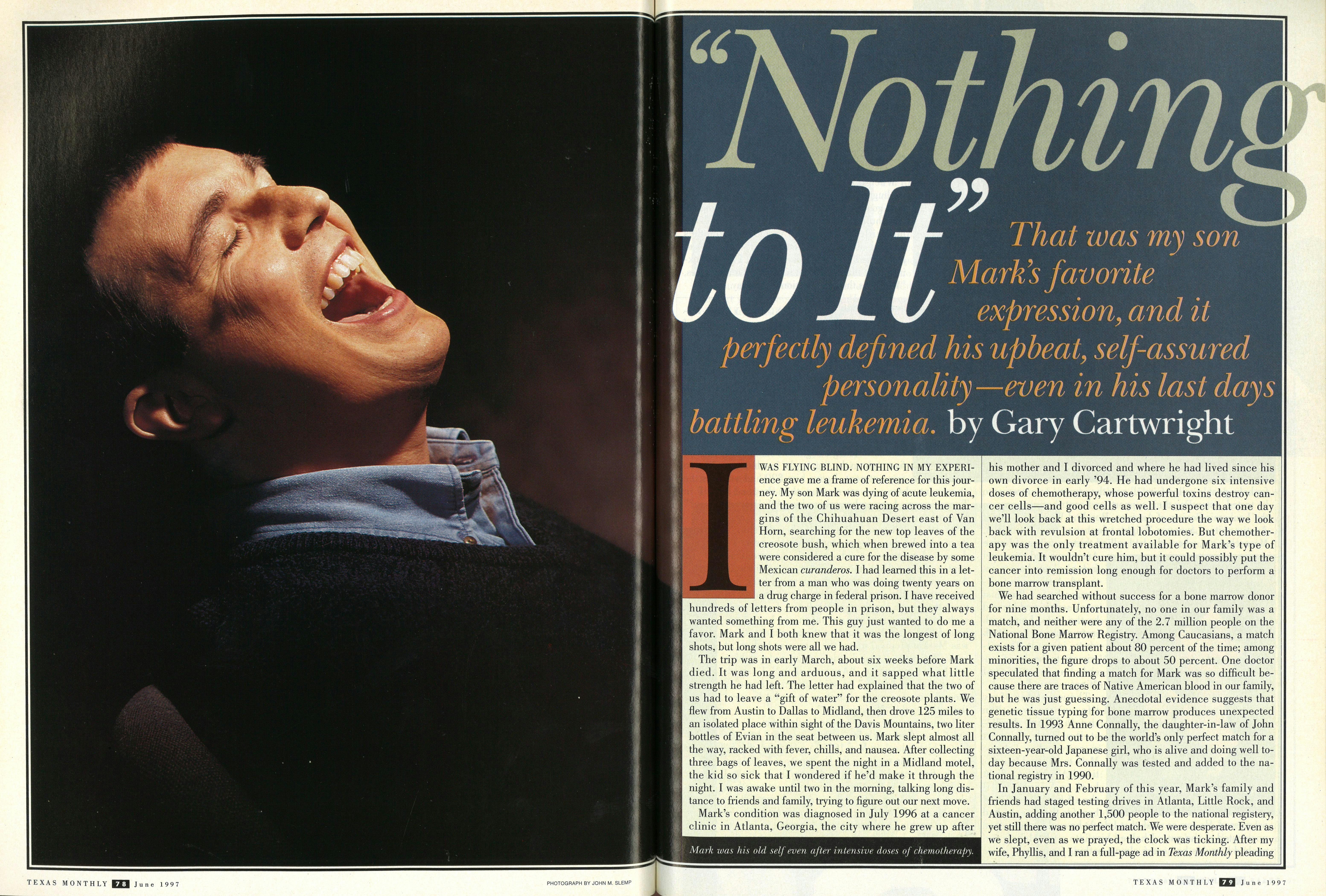

Sometimes we wrote songs, Markie strumming his guitar and me jotting down the words. We could compose an entire opera in an afternoon. When my friend Sue Sharlot graduated from UT law school, we wrote a number for her graduation party called, “All You Gotta Do Is Know the Law, Then Boogie Til You Puke!” Another all-time favorite was “Beat Me Like the Bitch I Am!” We wrote alternate lines, laughing so hard we could barely get the words out: “Reel and rod me / Marquis de Sade me / Makes me feel so fine / But beat me like the bitch I am / And tell the world you’re mine!”

We were never like father and son—more like brothers or best friends. He always called me by my nickname, Jap, never Dad or Daddy. He found it easier to express his love than I did, and in his effortless manner he taught me to express my love too. He also taught me to appreciate his favorite expression: Nothing to it. It was a manifesto of the indomitable spirit, an attitude that recognized no limit. I just naturally assumed Markie could do anything he set his mind to, and I guess he felt the same about me. Together, we thought of ourselves as unconquerable. And for many years we were.

IN GREEK, “LEUKEMIA” MEANS “WHITE BLOOD.” Mark had M-5 leukemia, the most severe type of adult acute myelogenous leukemia, in which immature white blood cells called blasts take over the bone marrow and prevent it from making enough normal white and red cells and platelets. The blasts overwhelm the mature white cells that fight infection, the red cells that carry oxygen, and the platelets that help blood clot, spilling into the bloodstream and infiltrating organs and glands until the process of life shuts down. M-5 is particularly nasty and extremely resistant to chemotherapy.

Scientists don’t know what causes leukemia, only that there are different types that react differently to treatment: Children’s leukemia can be cured, for instance, while adult leukemia is almost always fatal. Victims of chronic leukemia sometimes live for years because the blasts are more mature and progress more slowly, but eventually the production of immature white cells quickens, and chronic leukemia progresses into acute leukemia.

Aubrey Thompson, a friend at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston who has done leukemia research for twenty years, told me that Mark may have had chronic leukemia for the past ten or even twenty years, even though no one had detected it. “What makes adult leukemia so extremely difficult is that the cancer cells come and go, hiding out most of the time,” he said. “You go along for years, having a few bad days when you feel tired or run-down or flulike; then one day it explodes into acute leukemia. In childhood leukemia, by contrast, the cancer cells are very active. They come out of hiding and grow rapidly, and therefore they are sensitive to certain drugs and can be wiped out.”

A bone marrow transplant is the only complete cure for leukemia known at this time, but the process is long and dangerous, littered with formidable obstacles and treacherous ifs (if chemotherapy can force the cancer into temporary remission …). The transplant procedure is enormously expensive—it can cost up to $250,000—and it’s highly risky: Between 40 and 60 percent of those who undergo a transplant survive, and some survivors of the bone marrow transplant later succumb to fatal complications from graft-versus-host disease.

Of course, to have a transplant you must have a matching donor, another treacherous if: One in four leukemia patients who need a transplant never find a donor. Part of the problem is that most people have never heard of the National Marrow Donor Program. Among all diseases, leukemia is the number one killer of children—and it afflicts ten times as many adults as children—yet it is not high-profile. In a nation of more than 267 million people, fewer than 3 million are on the registry and fewer than 600,000 are minorities. Another problem is money. Because genetic tissue typing is so expensive, most people who are tested are asked to pay a fee, usually between $45 and $75 (since there are so few minorities on the registry, their tests are free). The cost aside, however, getting tested is really pretty easy. It takes only a couple of minutes: You fill out a short medical history and let a technician draw two small blood samples, which are sent to a national laboratory to be analyzed for the antigens needed to make a match; the identity codes of the antigens are then recorded in the national registry’s computer. If your antigens match a leukemia patient’s, you’ll be called in for more tests. Six out of six matching antigens are a “miracle match.”

At any point, of course, a potential donor can back out. Shirley Laine, the bone marrow manager of the Central Texas Regional Blood and Tissue Center in Austin, told me the heartbreaking story of Victor Ojeda, a nine-year-old Austin boy who died after a woman who was a perfect match decided she didn’t want to go through the ordeal of a transplant. It’s not really that much of an ordeal, though. As a donor, you spend a day or two in a hospital, during which time a needle is injected into your hip and marrow is extracted from the upper back part of the pelvis. You’ll have a sore butt for a week or two, but that’s a small price for saving a life. (To find the blood and tissue center nearest you, call 800-MARROW-2.)

I know now that even if we had found a miracle match for Mark, a transplant would have been useless. All that horrible chemotherapy had destroyed his immune system and had done great damage to his organs, but it never came close to stopping the cancer or putting it into remission. Mark’s doctor, Daniel Dubovsky, compared cancer cells to cockroaches: “You might kill ninety-five percent of them,” he told us, “but the remaining five percent emerge stronger and more resistant.” Dubovsky encounters only one or two patients a year whose cancer is so virulent that it resists the strongest chemotherapy. Mark happened to be one. “He lived nine or ten months longer than a lot of people who do go into remission,” Dubovsky said. “He had magnificent strength and energy.”

Two and a half weeks after our journey to the Chihuahuan Desert, while Mark was in the hospital, Dubovsky informed him that there was nothing left he could do. We were devastated. Markie said he’d like to go home.

PHYLLIS AND I FLEW TO ATLANTA FOR the deathwatch, not sure how we would handle it but trusting that Markie would set the style. Getting reacquainted with his longtime group of pals, we realized he’d set the style years ago. In high school he had put together a combination rock band and chili cookoff team called the Chain Gang, and they were with him until the end, honoring his wish that nobody feel sorry for him or for themselves. Tom “Meat” Smith, Markie’s oldest friend, sat at the foot of his bed and regaled us with stories about the Great Cartwright. It seems that the women of Atlanta were not quite unanimous in their devotion. Meat told us about one woman Mark jilted when he worked for the Turner Broadcasting System. To this day, she is unable to speak his name without pausing to spit on the floor. Meat demonstrated, feigning a high-pitched voice: “Oh, you must be referring to Mark … hock, spitooowee … Cartwright.” Sick as he was, Mark doubled over with laughter.

Also on hand was the latest and last of Mark’s girlfriends, Susan Shaw. She was as tough and as tenacious as they come. Almost single-handedly she had organized a drive that put five hundred new names on the bone marrow registry. She could have bailed out at any time—no one would have blamed her—but Susan wasn’t the type to bail. The only time she lost it was the day Dubovsky told the family it was over. “It wasn’t supposed to be that way,” Susan said later, her eyes swollen and red from a day of crying. “I had imagined our twilight years, sitting on the porch watching our grandchildren. Suddenly I just went to pieces. I was crying and calling out to God, saying, ‘Why Mark? Why me?’” Soon after, Susan got a phone call from the National Marrow Donor Program, telling her that she was a partial match for a 54-year-old man in the Midwest. “God works in mysterious ways,” she concluded.

What got us through those last few weeks was Markie’s remarkable courage, the grace, dignity, and measured good humor with which he faced death. He had resolved to put his affairs in order, and that’s what he did. He dictated a will and made it known that when the end came he didn’t want the paramedics to resuscitate him. He asked that his body be cremated and his ashes scattered in the Gulf of Mexico. (One exception: Some of the ashes would be handed over to the Chain Gang, whose members would select an appropriate urn—most likely a cowboy boot—and take them each year to the chili cookoff in Athens, Georgia.) He selected a Cajun friend, Jonathan “Gator” Ordoyné, as his replacement in the Chain Gang.

I asked him if he was scared. “No,” he said, “strangely enough I’m not.” He had been sick for so long that what he really wanted was just “a few good days.” That became my prayer: “If you can’t give us the miracle of sparing his life, Lord, then grant our fallback position: a few good days, then let him die quickly and without pain or fear.”

My prayer was answered. Markie seemed to get better by the day. He got out of bed and spent several hours sitting in the sun. He was able to eat solid food and even hold down cups of the creosote tea. He went to a couple of movies with Susan, and the three of us spent an afternoon at the Atlanta Botanical Garden. We drove the rural back roads, where spectacular explosions of azaleas, redbuds, and dogwoods seemed to have blossomed specifically on Mark’s behalf, and had dinner at his favorite Mexican restaurant.

The time had come for me to go home, we both agreed. “You’ve got to go sometime,” Markie said, not unaware of the double meaning. My last night in Atlanta we had dinner at his favorite Thai restaurant, then Mark and Susan drove me back to my hotel. Standing there face to face in the parking lot was the hardest part. Neither of us wanted to drag it out. Mark kissed me and said he loved me. I said I loved him too. “I can’t bring myself to say good-bye,” I told him. “So, until I see you again.”

“Until I see you again,” he told me back. I turned toward the hotel entrance, knowing it wouldn’t be in this lifetime.

After that we talked daily by phone. Mark told me that he and Meat were driving to Augusta for the opening day of the Masters golf tournament. On Friday, April 11, he flew to Little Rock to visit his children, nine-year-old Katy and seven-year-old Malcolm. It was an act of sheer will: His fever had returned, signaling that the brief reprieve was over. He somehow made it back to Atlanta on Sunday afternoon and died early the next morning. His last words were to Susan. “I think this is it,” he said softly, closing his eyes. “I’m packing ’em in.”

DEALING WITH THE “WHY” QUESTION is the ultimate test of faith. It took me a while to realize that God is not there to answer “Why” questions, though He can help ease the other emotions that overtake a parent whose child dies: the guilt, the frustration, the anger. What should I have done? What could I have done? Phyllis told me that when her son Robert was dying of AIDS in 1994, she had an irresistible urge to hold him tightly, as though she might transfer her energy and her wellness to him. I felt the same urge.

Anger was the emotion that hit hardest and lasted longest. I was angry at his doctor and at the hospital for allowing him to waste away; there must have been something else they could have done. I hated the entire pharmaceutical industry for wallowing in profits while its researchers consistently failed to find cures. I even called my pal Aubrey Thompson to vent my anger. He assured me that research was doing the best it could.

I no longer waste time on guilt or anger. I miss Markie and think about him almost constantly—not the way he was at the end but the way I knew him for forty years. He hated negative energy. He wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Below you’ll find links to information on how to become a donor, as well as general knowledge about the disease and its treatments.

National Transplant Assistance Fund

International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry

National Marrow Donor Program Online

Bone Marrow Donor Worldwide

Leukemia Society of America