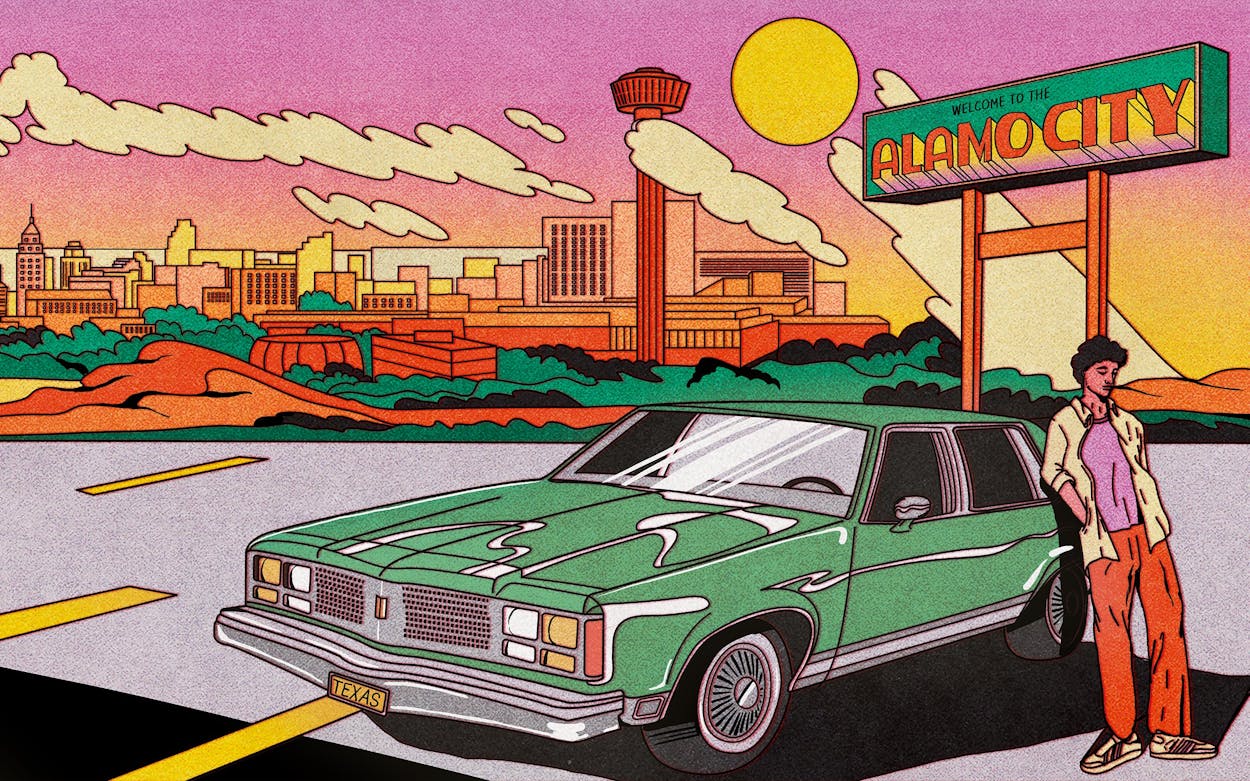

When I was fifteen and still a year shy of getting my driver’s license, my family made the five-hour drive from our home in Brownsville to my cousin Jimmy’s wedding in San Antonio. This was the summer of 1979, and most of us living on the border called the city “Sahn Ahn-toh-nyoh,” as it’s pronounced in Spanish, and not “San Ann-toe-nee-yo,” as I’d heard it pronounced in other places.

My parents and I left on a Friday afternoon and stopped along the way at a Whataburger for dinner. My mom had wanted us to eat in the car so we could get to San Antonio before dark because she was well aware of my father’s long history of getting lost in any city that wasn’t Brownsville. But my mother and I both knew he wasn’t going through no drive-through. My father had a hard-and-fast rule that no one could eat in his car, under any circumstances, especially if it involved hamburgers, which he claimed would leave a lingering stench on the upholstery and our clothes. He wasn’t going to show up to Jimmy’s wedding smelling like a #1 with extra onions.

My father was particular about his sage-green Oldsmobile Delta 88, which he’d bought used but treated like he’d driven it off the showroom floor. He washed it by hand every Saturday afternoon, starting with the hood, roof, trunk, bumpers, and taillights and then spending just as much time scrubbing the tires and whitewalls with an old horse brush. When he was done drying the Oldsmobile with a shammy, he’d park it under the carport so it would be ready to drive to church Sunday morning. The day before our trip to Jimmy’s wedding was the only time I remember him washing it during the week.

At the Whataburger we talked about whether I should apply for a learner’s permit that summer, something my mother was in favor of but my father wasn’t sure I was ready for yet. A few months back he’d taken me to the Brownsville Compress, an industrial park near our house, on a Sunday afternoon so I could practice driving on the empty roads and parking lots.

After a little coaching about where to keep my hands on the steering wheel, we began my first lesson. I shifted into drive, let the car move forward on its own, and focused on not gliding too close to either side. There was a curve in the road before it stretched out for another quarter mile or so and reached the first set of warehouses. I was still coasting along when we spotted an eighteen-wheeler moving in our direction.

“You okay?” my father asked. I nodded—if only because I was concentrating on the unexpected trailer and nodding took less effort than forming words.

I can’t explain what happened next. How the Oldsmobile began veering to the left, how it felt like some gravitational pull had taken over the steering wheel, how the truck driver laid on his horn and it made no difference, how my father let out some kind of guttural sound I’d heard him make when his horse wouldn’t back up, and how when that didn’t work he jerked the steering wheel to the right, hard, forcing us onto the shoulder just in time to dodge the oncoming truck and eventually stop in the tall grass near a ditch.

He had a few choice words for me, some in English but most in Spanish, none of which are printable in this magazine. Then we switched places and drove home. There would be other lessons, but that was the one that gave him some pause when it came to the learner’s permit.

Saying San Antonio is also a way of reclaiming the language that was, until the sixties, banned in Texas public schools, leading to Mexican American kids being punished in the classroom and on the playground.

People who don’t speak the language think it’s funny when they learn a bad word or two in Spanish, but in my case, because my father was from el rancho, meaning the backcountry, and spoke like it, I learned all the bad words in Spanish at the same time I learned all the regular words. Not that he didn’t also curse in English; it was just more colorful, poetic almost, when he let loose in Spanish. In our house it was perfectly normal for us to start a sentence in Spanish and finish it in English, or the other way around, or for one person to stick to Spanish and the other to English. Growing up this way, keenly aware of both languages, and then moving away from the border, I soon noticed some people were saying San Antonio and others were sticking to San Antonio.

Clearly, it’s a Spanish name, and no one with any sense of language would argue otherwise. But in this state, a Spanish word isn’t necessarily a foreign word, and hearing the city’s name said in Spanish is a subtle reminder that we’re living in a place that was once part of Mexico. Saying San Antonio is also a way of reclaiming the language that was, until the sixties, banned in Texas public schools, leading to Mexican American kids being punished in the classroom and on the playground. Even after the ban ended, many of these students were so traumatized they would later opt to not speak Spanish to their own children, and over time, younger generations lost their proficiency with the language.

I should also make clear that my parents were sometimes speaking English when they said San Antonio. And if for some inexplicable reason they had woken up the next morning suddenly speaking German or Greek or Swahili, they still would’ve said San Antonio when it came time to say San Antonio.

The hotel where we stayed for the wedding was located downtown. My father pulled the Oldsmobile up to the curb, turned on the flashers, and walked inside to check us in. After he came back out, my mother and I carried the luggage to the elevator while he drove the car into the hotel’s parking garage.

The plan was to attend Jimmy’s wedding on Saturday morning, then the reception at noon, and by midafternoon be on the road headed to Houston, where we would visit my sister for a few days before the long drive back to Brownsville.

My cousin Jimmy, who now goes by Jim, is technically my first cousin once removed. It was Bea (pronounced “Bay-ah”), his mom, who was my first cousin, even though there was an age difference of more than thirty years between us. My dad had been close to her since her father died when she was twelve, and later, Bea was living with my parents when she met her future husband, Félix. Being that she was my father’s favorite niece, there was no question that we’d be at Jimmy’s wedding and reception.

The next morning, my father was still getting ready when he tossed me the keys and told me to get the car. He had shaving foam on his face, but from the eyebrows up it looked like he was smiling, like he’d woken up in a good mood and now trusted me.

The hotel’s garage was three flights of stairs beneath the lobby and looked abandoned except for four or five other parked cars. I backed the Oldsmobile out of its space and headed up the circular ramp. When I reached the ramp on the first level, I was blinded briefly by headlights coming toward me, but unlike during my driving lesson, I had the sense to just stop in my lane to let the driver pass me by. But then a moment later, in that instant between taking my foot off the brake and wondering how much to step on the gas pedal to go up the ramp, the Oldsmobile lurched backward and smashed into the wall.

The sound was worse than the damage but not by much. The rounded edge of the chrome bumper was dented and the passenger-side taillight was shattered, leaving shards of red plastic on the ground where I was now standing in the black loafers my mother had bought me for Jimmy’s wedding.

I managed to quickly pull the Oldsmobile up to the curb and pop the trunk just as my parents came outside. I took the two valises from my father, contorting myself to block his view of the damage as he circled around the back of the car and my mother moved toward the passenger door.

“You brought the car?” he asked me once we were all inside.

“You told me to.”

“I meant for you to ask them at the front desk.”

“But look, he did it himself,” my mother said, all proud, as if I had just aced the parallel parking on my driving exam.

He nodded, not looking fully convinced, and tapped on his blinker to make a right turn. We would be eating breakfast first—pancakes, my father had already decided, though he liked to call them hot cakes or panqueques—and afterward heading to the church.

He parked the car facing the front door of the restaurant. Over breakfast, I half listened to my parents talk about wanting to visit with Bea and Félix at the wedding reception, but mainly, I wondered how long I could hide the damage. If I could somehow keep my father from finding out until we reached Houston, a good two hundred miles away, maybe I wouldn’t be blamed for the shattered taillight.

Parking wasn’t nearly as convenient when we arrived at the church, and my father had to nose into a space that faced the opposite direction, toward I-35, which even on a lazy Saturday morning was way busier than the one freeway we had in Brownsville. I hustled out of the back seat and again positioned myself at the rear of the car in a way that obstructed my parents’ view of the damage.

It must have been a lovely wedding, but I wouldn’t know since I spent most of the time looking over my shoulder at the parking lot, hoping, praying even, since we were in a church, for some reckless driver to plow into the Oldsmobile. If my dad had forgotten to lock the door, someone might even steal the car. I wanted to believe that anything was possible, but in the end, when the procession followed the bride and groom out of the church, I couldn’t stop my father from peering across the parking lot.

“¿Y eso?” he said to me, gripping me by the shoulder.

“What?”

“You know what.”

“What is it?” my mother asked, recognizing his tone.

“Mira,” he said, pointing with his chin, still nicked from shaving. She looked in the direction of the car, her eyes widening as she saw the taillight, and then, just for her, he added, “He did it himself.”

There was a lot more to say on the subject, but there were too many people around for him to let me have it, whether in English or Spanish, and it was also right then that Bea and Félix walked up and my mother reached out to hug her and then stepped aside for my father to do the same. Because we didn’t have the address or name of the banquet hall, Bea was giving my father directions to the reception when Félix jumped in and said, “N’ombre, just follow us so you don’t get lost.”

A few minutes later, my father was still squatting next to the bumper, unscrewing the tiny shattered bulb that had once been part of his taillight, when Félix tapped on his horn from across the parking lot and Bea waved for my parents to follow them.

Félix looped under the freeway and veered onto I-35. It was only because my father was trying not to lose Félix and Bea in the heavy traffic that he wasn’t talking about his busted taillight. We were directly behind them in the passing lane, farthest to the left, when without so much as signaling, Félix suddenly cut across three lanes and took the exit as if he’d forgotten we were following him. Boxed in by an eighteen-wheeler, my father hit the horn repeatedly, not for the truck driver but for Félix, who was now coasting down the frontage road.

“¿Y ahora?” my mother said after a while. “What are you going to do?”

We had passed another exit and my father was still in the left lane, cruising along and looking as calm as I’d seen him all morning. It seemed like he understood things. As hotheaded as he could be, he also liked to tell me that if a problem has a solution, there’s no need to worry. And if it doesn’t have a solution, you still have nothing to worry about.

There was nothing he could do about the wedding reception, as nobody had cellphones in those days. There was also nothing he could do about the bumper, so he was doing the one thing he could do, which was drive. Years later, we’d still talk about the day Félix, without any warning, darted for the exit and left us stuck in traffic, but we never talked about how that same day I had wrecked my father’s Oldsmobile. So yes, in a roundabout way, my prayers were answered.

“¿A dónde vas?” my mom asked, wanting to know where my father was taking us.

He waited a few seconds and said “Houston,” in English, because that was the only way to say it.

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “What We Say When We Say San Antonio.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- San Antonio