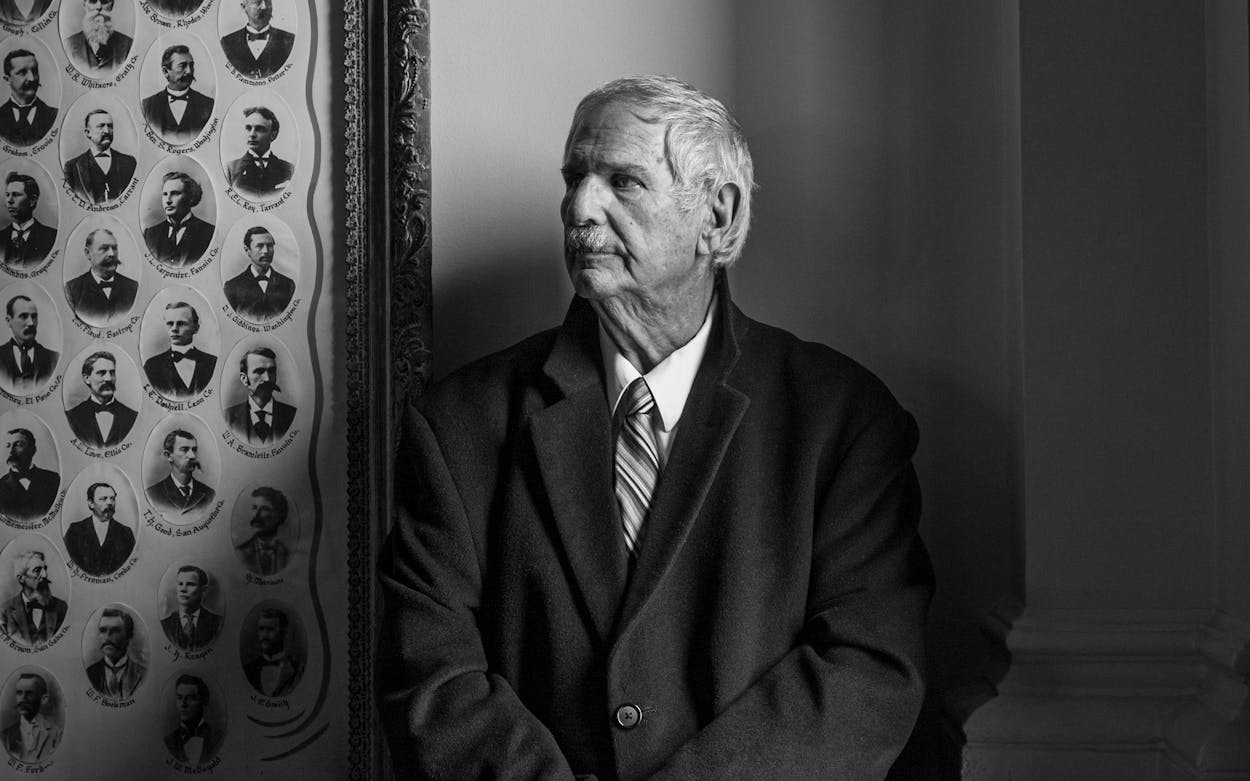

With Paul Burka’s death on August 15 at age eighty, there are almost too many losses to count. Born in Galveston and educated at Rice University and the University of Texas at Austin School of Law, Paul loved Texas and knew more about it than anyone else at Texas Monthly, where he worked as an editor and writer from 1974, a year after the magazine’s founding, until his retirement in 2015. He knew the state’s tiniest towns, its best barbecue, its worst small-time politicians and best baseball players. More important, he knew what Texas should be and could be, and he devoted his life to trying, heroically, to make it so.

All these qualities made him, in turn, a great journalist, one who knew intuitively what Texans wanted—and needed—to read. Swimming holes and chili were as coverage-worthy as governors and senators, and even Chevy Suburbans, all of which fell within his purview. He had vision to spare in that way. Paul scared the bejesus out of Texas politicians who knew he could always outthink them, see through them, and try to shame them into doing the right thing. “Paul was a thorough and knowledgeable journalist,” George W. Bush said in a public statement. “He understood state government as well as any Texas reporter, and his voice will be missed.” Rick Perry still remembers his first impression of Paul, back when Perry was a freshman state representative in the eighties. “He was larger than life,” he told me. “When he showed up in the back of the chamber during the last two weeks of session, people would be straightening their ties, clearing their throats as they headed to the back mic—he was the ringmaster, really.”

That ringmaster status was cemented pretty much from the get-go: Paul’s first contribution to Texas Monthly was helping craft the magazine’s first Best and Worst Legislators list, in 1973, before he was officially employed by TM. “Paul was all about judging politicians not by their politics but by their effectiveness and their character,” Bill Broyles, TM’s founding editor, said. “Could they get things done? Could you trust them? If that was yes, you made the Best. If no, you made the Worst. As I recall, Burka suggested a third category, Furniture, for legislators who were indistinguishable from their desks.” The list quickly became a mainstay of Texas politics. Former House member Bruce Gibson called it “the Academy Awards for the Lege—a lot of media gave awards; none had the salience of TM. Some guys shaped their whole sessions to try and get on it. If you got a spot on the Worst list, it definitely had a huge impact on your reelection. It guaranteed you an opponent.”

That combination of being dedicated to the well-being of Texas and having deep knowledge of how Texas politics really worked meant there was nowhere to hide for politicians who weren’t up to snuff. “I asked Paul once, ‘How does it feel to be an assassin?’ ” recalled Cliff Johnson, a former state representative who went on to serve as a top adviser for governors Bush and Perry. “And he said, ‘I’m not an assassin; I’m a recorder of suicides.’ ” Up to the end, Paul never held back in his judgments of our elected leaders. “He has no ideas, but he knows the name of every precinct chairman in Texas,” he once said of our current governor, having no ideas being about the worst thing Paul could think or say about anyone.

He was also, of course, a great editor, one who reminded us constantly that our primary obligation was not to our subjects, no matter how rich or powerful, but to our readers. He hated the back-and-forth he said, she said of newspaper reporting and always pushed us to do the hard work of sorting through the counterclaims and guiding the reader toward what was right and true. He always made even the best pieces better—and everything had to be the best in his eyes before it went into Texas Monthly, even a dumb gossip column I wrote many years ago. (“It’s flat,” he said of my copy, as if he were describing a roadkill platter situated in the center of an otherwise glorious banquet table.) He was confident in his beliefs. Arguing with Paul could be bracing but never nasty—he just wore you down until you saw that you were sadly misguided.

Paul was also generous with all that he knew. He was a natural mentor, eager to share, as virtually all Texas Monthly writers and, later, his students at UT-Austin learned. Maybe because he adored his wife, Sarah, and daughter, Janet, as much as his sons, Barrett and Joel, his expectations for women—“girls” to him, yes—were the same as for the guys. You might not have recognized your story when you got an edit back, but you learned from the experience, if you were smart. Eventually your drafts would come back bearing some resemblance to what you had written. “All the sentences were mine,” one writer bragged of his award-winning story. “Just in a different order,” quipped Paul, his editor.

But maybe the most wonderful thing about Paul—and the reason so many loved him so much, as I did and will to the end of my own days—was that he was as wonderfully flawed as he was brilliant and charitable. He was a man of prodigious proportions. He was the only staffer who could pose for a magazine spread on his head and still look august. But whenever he wore a tie, it came accessorized with a stain of mustard or barbecue sauce. He sometimes napped on a well-worn couch in his office, where he snored. He had absolutely no sense of time, which can be a problem in a deadline-centered world. “My pants were in the dryer” was maybe Paul’s best excuse for his perpetual tardiness, but it was certainly not the only one. He loved to call at 10 p.m. just to jaw for, like, a minimum of an hour. (One fellow writer used to read—magazines, books, newspapers—while she listened to him on the phone because he didn’t come up for air all that often.) Popular culture was lost on him; “What’s Motown?” is another infamous Burka quote. And he became so enamored of certain politicians—Henry Cisneros and George W. Bush, in particular—that they broke his heart a little when they revealed themselves to have feet of clay.

The only solace to be found in Paul’s death is that he gave so much when he was with us. He wasn’t just the institutional memory and the conscience of Texas Monthly, he was its soul. Everything the writers and editors strive to offer our readers is because of him and the example he set. None of us could bear to let him down, even now.

The following are remembrances by other Texas Monthly colleagues.

Michael R. Levy founded Texas Monthly in 1972, and he served as our publisher from the first issue in February 1973 until the close of the September 2008 issue.

There are many smart people, but few of these smart people have wisdom and common sense. Paul Burka had large quantities of both. With his acute understanding of the human condition, Paul was able to shine his little light on Texas politics, giving Texas Monthly’s readers an understanding of the process that affected their lives, explaining what made the difference between the too few elected and appointed officials who wore white hats and the too many who wore black ones. George Christian, press secretary to President Lyndon Johnson, described Paul as one of the four or five best political writers nationally. His body of knowledge extended back to 1966 when he began working in the Texas Legislature for Senator Babe Schwartz. It’s safe to say Paul was a political junkie.

Politicians who hated what Paul had to say still wanted to spend lots of time just yakking with him because they respected him. And he made them laugh.

A great tribute to Paul is that Democrats thought he was a Republican, and Republicans thought he was a Democrat. Like the umpires at Disch-Falk Field, Paul called ’em as he saw ’em. And what he wrote was never mean.

Texas Monthly never had the editorial resources of national magazines. Paul taught us all that excellence is primarily a product of a commitment to excellence, with money providing the icing. Paul’s passion for Texas Monthly lifted us all.

Paul’s mentorship showed talented young writers how to be very talented great writers.

We all have our good points and our bad ones, our plusses and minuses, and Paul had just a few. In Webster’s New Collegiate, under “firetrap,” it says “see Paul Burka’s office.” And Paul never faced a deadline that couldn’t be ignored for the sake of a UT baseball game. I believe the copy editors and fact-checkers too often thought of the possibility of combining tar and feathers and Burka. Many times Paul probably prompted Bill Broyles, Greg Curtis, and Evan Smith to think of something much worse.

Most important, Paul was a nice man, a good man, a funny man, a caring man.

“Mensch” is a Yiddish word. It means a person of honor and integrity.

Paul was a mensch.

He will be missed. A lot.

William Broyles was the magazine’s founding editor, serving until 1981. He went on to a career as an acclaimed screenwriter, receiving an Oscar nomination in 1996 for Apollo 13.

Paul was one of the Texas Monthly Originals. I met him at Rice University in 1962, the same day I met Griffin Smith and Greg Curtis. Griffin was editor of the Rice Thresher and Paul the sports editor. They convinced me to come try it out, which is how I got into journalism. The four of us were among the original brain trust of Texas Monthly back when it was still a gleam in Mike Levy’s eye. At Rice Paul played bridge in the dining commons every afternoon and evening. He roped me into bridge too. Between bridge and the Thresher, I didn’t study enough and failed freshman math. That was the thing about Paul, he could be an inspiration and a distraction, and was brilliant at both.

He was, how shall I say it, occasionally lacking in self-discipline about deadlines and personal appearance. During long editorial meeting days, Paul would go out for doughnuts and barbecue and return covered in crumbs and sauce stains, carrying empty takeout bags. That lack of discipline in areas he simply didn’t think were important stood in stark contrast to the incredible discipline of his mind. His memory was prodigious, but it wasn’t the memory of a parlor trick, it was memory married with wisdom. Paul never forgot a box score, a bridge hand, or a legislative session.

Paul couldn’t officially work for us at first because he was employed at the Legislature through the end of the 1973 session. His first contribution was to collaborate under the table with Griffin and Richard West on the first Best and Worst Legislators list we inaugurated in 1973. Paul was all about judging politicians not by their politics but by their effectiveness and their character. Could they get things done? Could you trust them? If that was yes, you made the Best. If no, you made the Worst. As I recall, Burka suggested a third category, Furniture, for legislators who were indistinguishable from their desks.

His first signed story was a beautiful and evocative eulogy on the demolition of Clark Field, the legendary UT baseball park. For the first four years he worked at the magazine, he devised a monthly puzzle for the back page that exploited the corners of his mind that played bridge at master level. Then he had a sports column and went on to own the political beat. For decades he was the best political writer in Texas and arguably in America.

With his law degree, he could also handle huge and complex stories like his two-part story on Clinton Manges (still one of the longest stories Texas Monthly has ever run) and his cover story on how Coastal States company had taken over the Texas energy markets much as Enron did years later. His bridge background, which had taught him about bluffs, options, calculated risks, and strategies, let him enter the minds of the whiz kids who had gamed the system. Paul was also a great polemicist. The cover image of his “I Hate Chili” was Paul turning thumbs down on a bowl of red. He was Team Barbecue all the way.

But where Paul truly showed his worth was as an editor. Many great writers aren’t so great as editors, because they fall back on telling you how they would write your story. Paul was brilliant at understanding what you wanted to say, and then devising the simplest and clearest way to achieve it. He was my main editor on my “Behind the Lines” editor’s column and every feature I wrote. He kept me from falling into cliché, nonsense, bombast, self-importance. He did the same for everyone, for generations of writers. He cast his editing net across everything we did, from features to captions. The spirit of Texas Monthly, that would be Paul. He was the guardian of its soul, its gatekeeper, its conscience.

Paul loved Sarah and he loved his kids. He loved Galveston. He was BOI (Born on the Island), and once you really got to know him you learned how important to him that was. It had nothing to do with the beach—Paul was the least beachy person I knew. It had to do with its history, its smells, the complex family trees, the Gothic politics. I remember one time we crossed the Causeway from the mainland and I could feel Paul settle into his Galveston Island self.

I’m home, he said.

I hope so. Bless you Paul, I owe you so much. We all do.

John Schwartz is a professor of practice in journalism at the University of Texas, after spending 21 years at The New York Times.

Before Paul Burka was Texas Monthly’s revered (and feared) politics maven, he was a legislative aide for state senator A.R. “Babe” Schwartz, my dad. Babe Schwartz was a formidable, if somewhat diminutive, figure, but Paul could go toe to toe with him. Paul loved to tell the story of a report Dad had him write up on beach policy in 1969. Dad was expecting your plain-vanilla legislative report. Instead, Paul bound it in a four-color magazine stock cover with a beach scene and with the title “Footprints . . . on the Sands of Time.” Paul always laughed when he’d tell the story of Dad raging and cussing at him for that bit of literary showmanship, when all he’d wanted was a simple report on the findings of the Interim Beach Study Committee. He’d imitate Dad saying scornfully, “Footprints . . . on the Sands of Time?!” Paul especially loved telling that story over dinner with Mom and Dad and Sarah—and there were a lot of those dinners, because that was a deep, loving, and long friendship, with the conversation picking up where they left off and rolling on till dessert. (It was a good report! You can see it here.) Dad appeared on Paul’s ten-best legislators list four times. Some might have said the fix was in because of their long-standing relationship, but Paul didn’t care. Dad was just that good, he said.

So a generation later, I was working part time for Paul at Texas Monthly as a researcher. It was the early eighties, and I was in law school but wanting to go into journalism. One day Paul pulled me aside for some career advice: “Johnny, you know your world very well. But it starts at the river and ends at Twenty-ninth Street.” I knew the Legislature and the campus, he was telling me, but I needed more. He told me to build a career elsewhere. Best advice I ever got, even though it hurt to hear it.

Gregory Curtis came to Texas Monthly in 1972 as part of the original staff. In 1981 he became editor in chief, a position he held until 2000.

Paul was always late, but Paul was always right. I first met him in the fall of 1962 when I entered Rice University. He was a senior, an acknowledged savant in history, the best bridge player around, and a power hitter in softball. I saw him again exactly ten years later in fall of 1972, when I moved to Austin to join the nascent Texas Monthly. Paul was living in Austin too, having gone to law school at the University of Texas. He was working as, in his words, a “political hack.” After a few issues Bill Broyles, the first editor, hired Paul and the pulse of the magazine immediately quickened. His stories always came in late, but they were always worth the wait.

When I became editor in 1981, I found myself relying on Paul more and more as a writer but also as an editor. I wrote a column each month and I always turned in my copy to Paul for his advice and counsel. Paul knew how to make the argument more convincing and the narrative more clear and dramatic. He could see mistakes in structure, that your fifth paragraph should be moved up to first, and that your first paragraph should be saved for last. When my work satisfied Paul, I stopped worrying. I knew the story was solid. And his influence spread across the whole magazine. I’ve talked to others who worked closely with him and we all agree that Texas Monthly would not have thrived without Paul—and it might not have endured.

And it wasn’t all work. Paul loved to sit and talk, maybe a little too much as deadlines approached, and it was a great pleasure to talk with him. He talked about the Legislature, books, UT football, the Astros, historic Galveston, what comic crisis had made him so late, the qualities of good barbecue, and so much else. Paul may not have thought that he was teaching, but he would be astounded to know how much I learned from him.

Patricia Sharpe has been a staff writer since 1974.

The magazine’s readers knew Paul as an expert in Texas politics. To the staff, he was a writing professor in residence. He edited numerous stories large and small, and the comments he wrote in the margins were legendary. He caught your embarrassing errors in spelling and grammar and would offer detailed step-by-step instructions on giving a story a dramatic arc you didn’t even realize was missing. I especially remember him emphasizing the importance of the last sentence in a paragraph. “That’s where you lose readers,” he warned. “The final sentence can’t always be a cliffhanger, but it can pose a question or raise an issue that piques their curiosity. You’ve got to keep people engaged. You need to make them care.” That sounds like pretty good advice for life, come to think of it.

Nicholas Lemann, a former executive editor, wrote for Texas Monthly from the late seventies to the mid-eighties.

I met Paul 44 years ago, in the spring of 1978. I was working for a perpetually struggling liberal political magazine called the Washington Monthly, but I had signed up to join the staff of Texas Monthly, which was definitely not struggling. Paul was in Washington and he called me up and said, “Let’s visit.” I hadn’t realized that visit was an intransitive verb—I guess that was the first step in an extensive Texas education by Paul.

I was inhabiting a comfortable fantasy world of politics as a pure reformist crusade, meant to save a fallen world; Paul lived deep inside the real realm of practical politics. That was the main topic of my education. He believed that politics was an honorable and important endeavor, which existed to get things done that needed to get done, and that politicians were professionals to be admired—at least if they met his standards. He disdained only the incompetents, the showboaters, and the ideologues. Paul had come of age in the era when Texas was still a one-party state run by tough, unsentimental, seigneurial conservative Democrats. In politics he was the classic tough guy with a soft heart, which was broken (tough guys’ hearts always are, aren’t they?) by the spectacle of the kinds of Texas politicians he admired becoming first Republicans and then conservative-movement Republicans. But he never gave up his fundamental faith in politics.

Just as Paul had volunteered to be the person to welcome me to Texas before I had even arrived, when I moved from Austin to New York, in 1986, he found out which flight I was on and showed up at the airport gate—you could do that then—to say goodbye. His signature gruffness was about a millimeter deep. What he really was, was tenderhearted.

David Anderson was a professor at the University of Texas School of Law from 1972 until 2018. He also served as a legal advisor to Texas Monthly from its founding in 1973 until 2018, under the title of contributing editor.

In the mid-sixties, Paul was a law student working for an interim committee in the Texas Legislature. I was in the state capitol bureau of United Press International and met Paul when he came through the press room trying to get us to write about protecting Texas beaches. I could not have imagined then that this perennially disheveled committee clerk would one day do more to shape the Legislature, at least for a few sessions, than anyone else.

In the seventies, there were a few people in Texas who believed state government could be a force for good, and Paul was one. Most of the believers saw goodness through an ideological lens, but Paul didn’t. He had the old-fashioned idea that legislators should be judged by neutral criteria: can they get things done, are they respected by colleagues, do they keep promises, do they represent the interests of their constituents? When the first installment of the Best and Worst Legislators list came out, many people were surprised to see that it wasn’t ideologically driven.

For a few sessions, the lists had a transformative effect on the Legislature; most members have political ambitions, so they kept Paul’s criteria in mind, whether they aspired to the Best list, of feared the dreaded Worst list or the almost equally shameful Furniture list. Reporters commented that deportment tended to improve, debate became more cogent, and grandstanding tended to subside when Paul was spotted in the chamber. As partisanship gained power in later years, Paul’s influence waned, but for a while it made the Legislature a better place.

Stephen Harrigan has been a regular contributor to the magazine since 1973. His most recent book is The Leopard Is Loose (Knopf, 2022).

Paul died just shy of the fiftieth anniversary of Texas Monthly, a magazine whose contours of style and integrity he did so much to shape. Could it have had the impact it did in the early years—and the longevity it earned issue after issue—without him? In a lot of ways, he was Texas Monthly’s center of gravity, the in-house expert on—among other crucial topics—politics, business, and food. (When it came to chili and barbecue, his opinion was law.) I’ve been spending some time today looking through back issues of the magazine and reencountering his writing voice while I conjure up memories of his speaking voice. In his writing he was calm, declarative, authoritative, but right now I can’t call to mind a conversation I had with him in which he wasn’t laughing and looking somewhat shyly at the floor. He was an expert on everything about Texas, past and present, but he never lorded it over beginning magazine writers like me who had a lot of catching up to do. (Thank you, Paul, for patiently explaining the Texas Railroad Commission to me.)

It is legendarily true, however, that tidiness and timeliness were not his most heralded qualities. His voice-mail box was always full, and he was often missing from his cluttered office for weeks at a time, sometimes impossible to track down. There was that time he was late to an important editorial meeting because he only had one pair of pants and they were in the dryer. In fact, Paul was always late—you could set your watch by him not being there. It can be no accident that his sister Jane Burka—who grew up with him—wrote the definitive book on procrastination. In Paul’s mind, a magazine deadline was as hazy and theoretical a concept as an event horizon. But he never missed a deadline, he just warped the idea of the magazine’s schedule—of time itself—around his own inscrutable biorhythms. He was a master of chaos, a disrupter of space and time, but somehow still and always the stable center of Texas Monthly.

Lawrence Wright was a staff writer at Texas Monthly from 1980 until 1992.

I first met Paul in 1980, when I came to Austin to interview with Texas Monthly. The meeting included Bill Broyles (who was still editor), Greg Curtis, Steve Harrigan, and Paul. It took place in the Pit, which was the closest barbecue joint near the office. I knew Paul was a great reporter and one of his assets was a delicious sense of humor. When he smiled, his eyes crinkled. I thought: this is a place where I’ll find friends.

Staff writer Jan Jarboe used to call Paul “The Franchise,” and it was true that much of Texas Monthly’s reputation was based on Paul’s reporting, which was informed by both his experience and his wit. He knew the political game better than anyone. He savored the great characters that take root in the Legislature, and while he was friendly to one and all, he never let affection cloud his judgment. Nor would he ever be mean to score a point. Paul was deeply respected even by those he criticized.

What I most treasure in memory is his kindness. He and Steve Harrigan edited an article my wife, Roberta, wrote for Texas Monthly about teaching in a highly stressed public school in Austin (“Do I Make a Difference?” September 1988). Roberta had never written for publication and the editing experience can be sobering. Paul gently talked her through it with all those years of experience behind him, helping Roberta make the best story possible—and the story was later nominated for a National Magazine Award. In our house, Paul was always spoken of with deep affection and gratitude.

Dick J. Reavis was a freelancer for Texas Monthly from 1977 until 1981 and a staff writer from 1981 until 1990.

Paul Burka was the house Republican at Texas Monthly during my tenure. As what one of my colleagues termed an “anarcho-communist,” I was at the opposite pole. Some of our writers and at least one editor at times voted for GOP candidates, but the general tenor of the magazine was liberal, though mildly so.

My first feature-length story, a 1978 eight-thousand-word piece about Maoist-led Mexican guerrillas, went through two drafts—each several weeks in composition—before Bill Broyles said that my submission was so misshapen that he had to “do triage” on it. But he also said that he would circulate it to lower-ranking editors to see if anyone wanted to save it.

Burka took up the task, but he didn’t simply sign off on a third draft. He told me that he had telephoned someone in the American embassy in Mexico, probably an agent of the CIA. The embassy’s representative said that according to his sources, all of the guerrilla groups in Mexico had been dismantled. In my drafts I had confessed to concocting the names of the tiny ejido villages that I had visited, saying only that they were in the states of Veracruz or Oaxaca. On a just-between-writer-and-editor basis, Burka asked for the real names of those settlements, saying that he wanted to see if they even existed. Because I knew he was a Republican and suspected that he might give them up to the CIA, I refused to divulge them. I suppose my writing career could have ended there because there are supposed to be no secrets between writers and editors. But the story ran as I had written it.

Paul Burka made possible my debut into magazine journalism. An anthology of my writings is due for publication in November and months ago, I dedicated it to him.

Joe Nocera wrote and edited at Texas Monthly from 1982 until 1986.

In the movie Shakespeare in Love, Mr. Henslowe, the theater manager, tells some anxious backers not to worry about the mess the rehearsals appear to be. “Strangely enough, it all turns out well,” he says.

“How?” one of the men asks.

“I don’t know,” replies Henslowe. “It’s a miracle.”

Once, a very long time ago, I was the editor of Paul Burka’s signature article, the Best and Worst Legislators list. It’s late at night—like 1 a.m. late. The presses are supposed to roll in less than 24 hours. Paul and his collaborator that year, Alison Cook, another legendary procrastinator, have turned in some copy but not a lot. I’m not going to say that there was panic in the office, given how often the magazine has faced this situation, but a certain nervousness permeated the air. It doesn’t help that Paul isn’t answering the phone.

Finally, Greg Curtis, Texas Monthly’s editor, sends me to Paul’s home to see how much longer he’s going to be. When I get there, I can see that he’s written a handful of pages. He pulls one more from the typewriter and hands them to me. “Take this to the office and I’ll have a few more pages when you get back.”

By 4 a.m., I’ve made three or four trips and delivered all the pages. But there’s no time to edit. They are quickly copy-edited, laid out on the pages, and shipped to the printer. When the magazine comes out a few days later, I read Ten Best and realize that every word is exactly right. It’s a miracle. Except it’s not: it’s Paul Burka delivering one more great story, just in the nick of time.

Peter Elkind was a staff writer at Texas Monthly from 1983 until 1990.

I first met Paul in 1983, after joining the Texas Monthly writing staff at age 25. Young and more than a bit foolish, I was reflexively resistant to suggestions about my writing. (I questioned the pitch-perfect addition of the word “pernicious” to my first-ever magazine story.) During seven years at Texas Monthly, I slowly learned that being edited well was a pleasure—and that there was no greater joy than a Burka edit. Paul was brilliant, incisive, and direct, explaining what I’d done wrong and exactly what needed to be done about it. Always with good humor.

Paul’s own stories were evocative and memorable, at any scale: from his epic, gothic tale about South Texas power broker Clinton Manges (Robert Caro had nothing on Paul’s portrait of Texas power and place) to his pithy and withering appraisals of Texas’ best and worst legislators to his takes on chili and baseball.

In the realm of Texas politics, where Paul’s clear-eyed judgment dominated for decades, he admired public-spirited competence, honesty, and decency, regardless of ideology. He reserved his harshest judgment for shameful behavior, less by those who were simply dolts than by those who surely knew better.

I learned much from Paul: from his work; from his personal friendship, which was always generously dispensed; and from how he treated everyone around him. In 2008, in an evocative piece about his family and his father, who died when he was four, Paul noted an example he had learned for his own behavior: “I have been married for thirty years, and I have never raised my voice to my wife in anger.”

He will be sorely missed.

Emily Yoffe was a writer and editor at Texas Monthly from 1984 until 1989.

When Paul was your editor, it often took a little (okay, a lot) of prodding to get him into the editing mode. But once he was there, something magical happened. His suggested new lines were always the perfect thing to say, the thing you would have said if you had Paul’s gifts. I remember how he described one hapless legislator in his annual Best and Worst list of lawmakers: “He’s not the first politician to paint himself into a corner, but he’s surely the first to survey the situation and then apply a second coat.”

Farewell to a man with a big talent, and a big heart.

Skip Hollandsworth has been a staff writer since 1989.

One afternoon, after spending a few hours wrestling with another horrible first draft of a story I had just turned in, Paul said to me, “You do understand, Skip, that the essence of good journalism is good thinking.”

“Huh?” I said.

“You string a bunch of anecdotes together,” he snapped. “That’s not writing. That’s collating. Your job is to push me to think about your story—to make me ask questions, to search for answers.”

Paul had all sorts of advice like that. For instance, he was constantly ordering me to write big-picture paragraphs that usually come toward the end of the first sections of feature stories—“paragraphs that tell the reader where you are going,” he said. He hated my obsession with adjectives (“Can you at least come up with one adjective that isn’t trite?” he once asked), and he invariably cut what I considered to be powerful, scenic endings to my stories, telling me I was “overdramatic” and “embarrassing.” I would throw up my hands and act offended, but the fact is that I was so delighted by his edits that I would always take credit for them when I was around other writers.

Paul, this comes way too late, but thank you for ripping my stories apart. If it weren’t for you, I’d still be collating.

Jane Dure joined Texas Monthly as a copy editor in 1989, became deputy editor, and stayed with the magazine until 2004.

I started at Texas Monthly in 1989 as a copy editor and left in 2004 as deputy editor, a highfalutin’ title that meant absolutely nothing: 179 or 180 deadlines. For much of that time, my job was to make sure the trains ran on time; that we got the editorial material to the printer so that we could make our print schedule. After all the anecdotes about Paul’s lateness with copy, I should not have to say more about my former job. But I will, especially given that I have discovered since my time at Texas Monthly how the lack of sleep can take years off your life and have wondered, What did Paul do to me? I have read much of what has been written by Texas Monthly writers I worked with about Paul’s blowing through deadlines and I got a little chuckle. I would like to remind them that they were often guilty of the same. Probably learned it from the master. With that said, I offer my nonwriter’s perception of the difference between Paul’s process and that of other writers: Paul never began typing until he had basically written a story in his head. He was unable to put crap on a page just to get started. Everybody else, confronted with a deadline, put crap on a page and then had to wrestle with the crap for days and weeks.

There was no better writer than Paul. My favorite story of his was about the wood chip market in East Texas. Only Paul could make a story about wood chips interesting. Perhaps, only Paul would choose to write a story about wood chips. If you love long-form journalism, you have to admire the wood chip story. I tried to find it on the Texas Monthly web site, to give a link, just in case anybody might be interested. Couldn’t find it, but I did see that Paul is credited with 3,663 stories.

I loved Paul Burka almost from the moment I met him. He was a big softie. He loved his family and was so proud of his kids. He had a clarity of thought that was calming in a crisis even if it was not good news. The morning of 9/11, there was only one person I wanted to talk to and that was Paul; everybody else was just chatter. Early in my days at the magazine, Paul took me to his favorite hamburger haunt near the office; it was in a parking garage. There, he taught me how to dress a hamburger for maximum taste value. I ended up eating at that place in the parking garage at least once a week, and to this day, I will not allow a slice of unripe tomato on my hamburger. I learned many other things from Paul, namely the importance of kindergarten. I had asked him about his criteria for the Best and Worst Legislators list, how to avoid political bias, and he said something along the lines of: They should behave like we are all taught in kindergarten. I have thought recently about who all must have failed kindergarten, or maybe kindergarten is different now. Paul’s Texas was a kinder, more well-wishing Texas.

It is true that Paul seemed unknowledgeable about contemporary things. After we went to computer files for all of the magazine’s editorial product, Paul kept using the old lingo of “boards” and the like. He didn’t realize we no longer had to run to FedEx with the “boards” to get Bum Steers, or anything else he was responsible for, to the printer in time, that we could push a button on a computer, even the next day. And we didn’t tell him. Actually, I told him—seemed cruel not to—but not for some time. I think it was Evan Smith who came up with the idea of fake deadlines for Paul. That worked for maybe a day. In the end, Texas Monthly needed the perfection of Paul, and sometimes, most times, all the time, we had to wait for it. It was always worth the wait.

Even though I suspect Paul will be responsible for my early demise, I would not trade those days, with that impossible man and the rest of that impossible magazine family, for anything. I would do it all over again.

Robert Draper was a staff writer at Texas Monthly from 1991 until 1997, and he still writes occasionally for the magazine. He also is a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine and National Geographic.

Thanks to Paul Burka, the state’s powers that be took Texas Monthly seriously. No other writer will have his command over Texas politics.

Still, I think of his influence on a more molecular level. On my first day as a staff writer, I was riding in the office elevator with Paul and another writer. He was justly extolling the talents of our colleague Mimi Swartz. “We’re reporters,” he said to us three. “Mimi is a writer.”

I took those words as a challenge, and absolutely no one helped bring me to the next level more than Paul did. “Good writing is clear thinking,” he always said. Coming from a person who could at times appear, let’s say, disordered, his incisiveness seemed magical. His own journalism was both elegant and fearless. He was the master of the top-editing memo, the directive that explained to you how your shell of a first draft could be made into a serviceable piece of journalism. Today, it’s hard to convey the artistry of these memos and the care he put into them. Paul wasn’t lacking in ego, but he never claimed to be the genius behind someone else’s byline. Instead, he took joy in shaping Texas Monthly’s intellectual framework, issue by issue. Paul Burka was a national talent, but he belonged to Texas.

Patricia Kilday Hart wrote Best and Worst Legislators for Texas Monthly from 1991 until 2011 and was a columnist for the Houston Chronicle until her retirement in 2014.

For twenty years of my life, in the first half of every odd-numbered year, I was tasked with assisting Paul Burka write Texas Monthly’s signature political story, the Best and Worst Legislators list. Covering the Legislature with Paul was a total immersion experience of early morning interviews, late-night committee meetings, phone calls at odd hours, and weekend strategy sessions. He always dressed in the role of Rumpled Reporter, was usually in want of a haircut and mustache trim, and on most days after lunch, a barbecue-sauced-stained tie draped over his ample belly. His easy charm and self-effacing chuckle made his subjects sometimes forget they were speaking to the state’s foremost political analyst.

Pity the politician who failed to take him seriously. Few did. Paul was an institution at the Texas Capitol. More than one House Speaker complained to me that it was impossible to get legislation passed when Paul was spotted on the House floor. Too many legislators would line up at the back microphone, hoping to impress him with their eloquence. They shouldn’t have bothered. Paul could spot a poser. His success as a political reporter rested with his uncanny ability to read people and intuit their motives.

Bob Bullock took him seriously. The late lieutenant governor, who possessed a legendary temper, fought constantly and loudly with Paul over his columns. Once, I was sitting at the press table of the Texas Senate when Paul raced up to me, out of breath and a little flustered. “Oh, thank God you’re here!” he exclaimed. It turns out Bullock had summoned him for another tongue-lashing. During the previous one, Bullock had become so angry that he snatched Paul’s reporter’s notebook out of his hand and refused to give it back. Paul, fearing another violent Bullock outburst, wanted me to accompany him to the lieutenant governor’s inner sanctum, gambling that a female presence would bring out the old Southern gentleman at Bullock’s core. “I’m not ashamed to admit that I want to hide behind a woman’s skirts,” Paul admitted with nervous laughter.

The strategy worked. Bullock vented about Paul’s latest column, but mostly behaved, and we both emerged from the meeting still holding our notebooks.

Evan Smith joined the staff as a senior editor in 1992, was deputy editor from 1993 to 2000, then served as editor until 2008, when he became president and editor in chief. He cofounded the Texas Tribune in September 2009.

For the nearly eighteen years I was at Texas Monthly—when I was an editor, and when I was the editor—I worked with Paul on every story he turned in. Big ones, little ones. Best and Worst lists, narrative features, columns, paragraph-long barbecue joint write-ups. In all that time I don’t think I was ever not mad at him. He could be incredibly frustrating. He blew through deadlines without so much as a second thought, and his made-up excuses for ghosting us until the literal last minute were legendary. But the copy he eventually turned in, and he always eventually turned it in, was clean, never in need of even the most basic rewrite. He was one of the best writers, one of biggest talents, I’ve known in journalism. He knew so much more than the rest of us about so many different subjects, and his insights were real insights. He got away with driving everyone crazy for so long because he was that good. If you worked with him you couldn’t stay mad at him. You had to respect him. I did. We all did. As much as it seemed like it wouldn’t be worth the trouble, it was.

Here’s how much I respected him: when I became the editor in July 2000, I inherited the first thing everyone read in each issue: the Behind the Lines column. My predecessor, Greg Curtis, had written it month after month for his entire tenure, as had his predecessor, Bill Broyles, before him. It was where the most trusted journalistic voice, the person in charge, had his say. But they had both been writers, and they were both Texans. I was still relatively new to the state—here at that time for fewer than nine years—and I had primarily been an editor my entire career. I knew what I needed to do. Right after it was announced that I had gotten the job, I let Paul know that I wanted him to write the column instead of me. His voice was the most important voice. He was the one everyone trusted. It was the best possible decision I could have made for Texas Monthly. I never regretted it.

Jeff Hart is an attorney in Austin.

For ten years, Paul and I were partners in the local fantasy-baseball league which, as many will know, is based heavily on pitching and hitting statistics. As a Rice University graduate who majored in math, needless to say, Paul was always the better part of that partnership. We would spend countless hours each evening on the phone discussing the statistical merits of our players and possible replacements. One late evening during one of those lengthy discussions, I heard a racket in the background of loud voices and door-banging, and Paul abruptly said he had to go and hung up. I turned to my wife, Patti, who collaborated with Paul on Texas Monthly’s legislative coverage, and said “that was weird.” I wondered if Paul was okay. Thinking about the day of the month, Patti said not to worry: it was date when the magazine was being finalized and put to bed, and the noise was the last gasp of editors demanding Paul’s article for that month. Paul loved baseball as much as he loved Texas Monthly.

Our fantasy team was quite successful, and Paul and I would regularly receive money for that success. One legislative session, I was testifying in support of a bill that was opposed by oil and gas company lobbyists. One lobbyist complained to Paul that Texas Monthly was compromised on reporting on the issue by the fact that I was married to Patti. Paul immediately responded that the marital connection should be the least of his worries, and proceeded to detail the financial success he and I shared together from our fantasy-baseball partnership.

Most people knew Paul as the public figure he was. I feel fortunate to have known him as a devoted father, husband, and friend.

Brian Sweany joined the Texas Monthly staff as a copy editor in 1996, became a story editor in 1998, deputy editor in 2007, and served as editor in chief from 2014 until 2017.

Paul Burka was the writer and thinker about Texas I had hoped to be. His longform stories—particularly his political profiles—inspired how I think about journalism and politics. Without Paul, Texas Monthly would not have become the institution that it is. Without Texas, Paul would not have brought to life the stories and characters he did. I remember he once remarked, “Isn’t it great to have the entire state as your beat?”

I first met him in the mid-nineties, when his hair was just turning silver but his reputation as a legendary writer and editor was already settled. I was a newly minted junior copy editor who had zero previous journalism experience. It showed. When I closed my eyes during that time I saw the word “stet” in Paul’s handwriting.

Paul was exacting and precise. I learned in those early days to come armed with sources for changes; of my suggested edits he would say with that wonderful, distinctive laugh, “You are like the mouse nibbling at the cheese.”

I could not understand how any single person could be so well versed on every subject of importance. And yet, as my colleagues have pointed out, part of the reason he was so likable was that he was wonderfully human. In one editorial meeting he provided an incisive critique of an upcoming election, only to ask later on during an unrelated conversation, “Who is Michael Jackson?”

Paul had no sense of time, no interest in formality or ego, no desire to return voice mails, and no concern whatsoever about pressure from sources wanting him to tip the scale this way or that. It was as if he existed in his own thought bubble, focused only on making each issue of Texas Monthly great.

Did I say “issue”? Because somewhere along the way, at a point when anyone else’s career would be winding down, Paul became the most important blogger in the state, an acknowledgement of his talent and energy but also a nod to the fact that God appreciates irony in all its forms. Paul understood that better than anyone.

And yes, the deadline stories are true. During one cycle, Jane Dure, our managing editor, repeatedly told Paul that we were actually a week later in the cycle than we really were, prompting him to turn in a draft several days early. During another issue cycle, with a week to go to press, he turned in a story at what he believed was the last possible moment. He then called a string of editors to let them know the story was in, frantically puzzled as to why no one answered in full-on deadline panic.

But the creation of art is its own mystery. Paul explained Texas culture better than anyone ever has in his four-decade career. As a young staff member, I was intensely interested in politics, and I read everything he wrote slowly and carefully, highlighting in yellow key facts and lovely turns of phrase. I created three-ring binders of Texas Monthly stories that I photocopied with great care each Friday afternoon for weekend reading. Some of the binders were categorized by topic (“LBJ,” for example); Paul had a binder all to himself, with a complete set of the Best and Worst Legislators lists.

I reread those stories from time to time, and I’m left with this thought: today we have so much information at our fingertips that we think we know more. Paul’s stories were so complete, so authoritative, and so artful that you learned and understood more. That’s the legacy I hope people will remember. God bless you, Paul.

Michael Hall joined the staff as a story editor in 1997 and has been a staff writer since 1999.

Paul was an enthusiastic editor on the page—sometimes subverting everything you thought you knew about your story. He was pretty enthusiastic on the base paths too. For years Texas Monthly had a softball team called the Fire Ants, a name that always seemed beer-league bland. We were also terrible; our slogan was “Texas Monthly: A great magazine, a terrible softball team.” Before the 2012 season, we sought to change our luck by changing our name. We were now the Burkas.

Paul, a huge Astros fan, was flattered by the name as well as his face on our early uniforms, which had a distinctly seventies Houston vibe (as well as his face on our sleeves). We were actually pretty good that year, going 6–3 as we prepared for our last game of the season. We got him to come out for it—and to coach third base. While the Burkas had some good players, we also had some young people who had rarely played the game before—and had no idea what to do when they approached third base. Paul, who had recently turned seventy, let them know: Go home. It didn’t matter if someone was slow or fast, if the ball was in right field or the third baseman’s mitt—he waved them home. Those of us who thought we knew how to round third—Gauge where the ball is! Weigh the odds of beating the throw!—stood in awe as Paul jumped up and down, windmilled his arms, and urged the runners to the plate. And the thing is, he absolutely knew what he was doing and almost every runner he waved home was safe. The Burkas won the game, 18–10, the only time we ever played for our namesake. I’ve always thought a great editor is like a great coach, and Paul would have been one of the best.

Katy Vine was hired to write and edit our Around the State listings in 1997, and she moved to staff writer in 2002.

While I heard about Paul’s steel-trap memory when I first started working at Texas Monthly, I didn’t witness it until he edited a tiny piece I wrote in 1999 about a 1954 Allan Shivers TV ad. He scanned my draft, looked up at me, and asked, “Should we add that it ran on a Thursday?”

But as sharp as his memory was, it was focused on politics—pop culture might as well have been happening on another planet. I heard that when we wanted to reference Michael Jackson’s Bad on the cover, it became clear that Paul didn’t realize that Jackson had gone solo, and he asked something like, “The lead singer from the Jackson 5?”

David Courtney joined Texas Monthly in 2005 and in 2007 debuted his wildly popular advice column, the Texanist.

I somehow ended up landing in the office that Paul last occupied at the magazine, which I’ve always considered an unearned honor. One of my bookshelves, formerly one of Paul’s bookshelves, is filled with the first 25 years’ worth of Texas Monthly issues, an unintentional inheritance. This partial archive is stowed in boxes marked by year, from 1973 to 1998. The collection is complete, and well-kept, and most all of the magazines have a small handwritten note at the top of the cover: “Burka Office Copy.” The thought of such an orderly collection residing in a site of such disorder, as it formerly did, always struck me. I believe it says something.

Eileen Smith was an editor at Texas Monthly from 2007 until 2010.

Before I started at Texas Monthly, I had spent a good deal of time poking fun of Paul on my political blog. After all, although Paul was a revered political journalist with the institutional knowledge of a true scholar, he was still a card-carrying member of that old-school print media.

So you can imagine my surprise when Paul started BurkaBlog. To say he loved blogging is an understatement. He had a wicked sense of humor and that rare ability to make fun of himself, all while remaining the esteemed political giant of Texas.

On my first day I mapped out where Paul’s office was so I could avoid it, assuming that he’d throw something at me when I walked by. Instead, he invited me in and we talked politics for a good two hours. Imagine that.

I’ll miss him.

Jake Silverstein joined the staff of Texas Monthly as a senior editor in 2006 and served as its fourth editor from 2008 to 2014. He is the editor of the New York Times Magazine.

It’s hard to believe in the passing away of people, like the great Paul Burka, who were such fixtures in their worlds. For more than forty years, Paul was a constant presence in the world of Texas journalism. He was like a lighthouse: always there, always on, confidently jutting forth into the stormy seas of Texas politics with benevolent wisdom and a deep commitment to keeping everything on the right track, which for Paul was always the moderate one, the sensible and hopeful path. Paul could write about anything, but politics was his great subject because he cared about people, and I think he saw the state politics as the realm in which we hammer out how we’re going to treat each other, which he felt should be done with compassion. Increasingly, as the state’s politics became more one-sided and more radical, the signals from Paul’s flashing beacon came to seem more dire. Still, even those politicians who Paul seemed to be warning us against seemed to take some comfort in his steady presence. He was always there.

I first met Paul when I joined Texas Monthly as an editor in 2006. Over the next eight years, until I left the magazine in 2014, Paul wrote God knows how many features, columns, and blog posts. The number must be finite and knowable, but it feels boundless, eternal, cosmically large, not only because Paul was always such a productive writer (something editors notice), but also because his productivity always had a magical air about it. Paul, as many people have noted over the years, was absolutely terrible with deadlines. Despite writing countless cover stories over the years, despite captaining dozens of editions of his franchise, the Best and Worst Legislators, and despite having been the principal writer of the monthly Behind the Lines column since taking it over in 2000, despite being a fixture, in other words, a noble lighthouse from whose steady pulses so many of us charted our courses, pretty much every assignment Paul took on always seemed on the verge of catastrophically not happening.

He would usually wait to start writing until the last moment. If you called him to inquire about how things were going you might catch him out reporting, or at a University of Texas baseball game, or going to get some barbecue, and he’d cheerfully assure you that everything was coming along. If you nervously stuck your head into his office a day or two later to see if things were coming along, you would be greeted with an alarming spectacle of chaos—papers everywhere, towers of books, yellowing certificates from some bygone honor, empty soda cans (Paul always drank Diet Dr Pepper, at least when I knew him, and always through the corner of his mouth), a suit jacket slung carelessly over the arm of the couch (where he liked to nap), maybe a half a sandwich awaiting further inspection—and behind it all, the dean of Texas political journalism staring at his computer screen with a look that did not always inspire confidence.

When it was all over, and Paul had somehow managed to produce yet another incisive, informative, funny piece of writing, one that combined a mastery of technical detail (many of those papers and books clogging up his office were full of the arcane documents of state government) with a keen sense of the bigger picture and a few good jokes, you might find yourself wondering how it all happened. When exactly did it get done?

Honestly, this was never clear to me. I don’t even think Paul quite knew the answer. There was a bumper sticker in his office, amid all that mess, that said, “Another deadline, another miracle,” and this was a sort of credo. There would always be another miracle. If you did the reporting, which he always did, and you thought deeply about the issues, which was his natural state, and you eventually sat yourself down in the chair and began to work, the miracle would arrive at some indeterminate time between when your anxious editor called during the baseball game and when your story shipped to the printer. None of it was explicable by natural law.

In retrospect, the miracle that regularly visited Paul was one of the most memorable things about working with him. He was unquestionably a master, one of the most consequential political journalists Texas has ever seen, a deft editor, and a mentor to dozens of younger reporters. But faced with a deadline (and he wrote so much that he was basically always facing a deadline) he was rendered powerfully vulnerable, and he didn’t seem to mind that. Paul was not vain; he made no effort to conceal the messiness of his process (one of his famous excuses for being late was that he had run over his own laptop in the parking garage). He was comfortable placing himself, month after month, at the mercy of the divine spirits of deadline journalism.

Maybe that’s where his trademark compassion came from. He knew that even if you had accomplished a great deal, and become a master of your craft, and were willing to keep pushing yourself hard every time, there was always the possibility, however small, that things might not come together. Still, what else are you going to do but get to work?

Paul Knight has been an associate editor at Texas Monthly since 2011.

Paul Burka was one of the people who terrified me when I started at Texas Monthly. I had no real reason to feel this way. I had never met him, but I knew his name, knew who he was, and I couldn’t imagine sparring with him about any detail in a story he wrote. I stole his chair by accident at the very first editorial meeting I attended. I don’t think I’d worked at the magazine for a week. I would later learn—and the details on this are a bit fuzzy—that for years, at every one of those meetings, Paul sat somewhere near the middle of the conference table next to Pat or Mimi. But I just walked in, saw an open seat at the table and sat down. As I remember it, the room gasped. I still don’t feel all that comfortable sitting at the conference table during those meetings.

A couple months after the chair incident, Paul stopped me in the hallway at the office. I was working on a story about Rick Perry’s presidential campaign. Paul hadn’t reported or written the story, at least not all of it, but he had been reading drafts. Somehow he knew I was fact-checking the piece, and he wanted to know all about the story and who I’d talked with. He was particularly interested in a massive South Texas flood that had helped Perry win his race against John Sharp for lieutenant governor in the late nineties. He was interested in all the details. That’s really the first time I met Paul.

Erica Grieder is a business reporter with the Houston Chronicle. From 2012 until 2016, she worked alongside Paul Burka as a senior editor at Texas Monthly, focused on politics

When it comes to Texas politics, Paul Burka really classed up the joint—obviously, a daunting task. Before I worked with him on Texas Monthly’s biennial Best and Worst Legislators list, I hadn’t realized just how much research and how many conversations go into those picks. The write-ups are stylish and snappy, but the deliberations are sincere. In making his picks, Burka always emphasized values that were close to his heart and that any public servant would do well to internalize: collegiality, problem-solving, respect for the professionalism and expertise of staffers, concern for the most vulnerable among us. At times, Burka seemed amused by the political theater the Texas Legislature is famous for, but he paid close attention to what was going on beneath the surface, and sincerely appreciated legislators of both parties who put the public good first.

The comments section on his BurkaBlog was a good online analog to the discussions he would lead on panels, at events like “Bar Poll,” or in the hallways of the Capitol extension—where his every appearance would set first-year legislators aflutter and where he ran into an old friend at every step.

Burka was a gentle man; in a world of poker players, he preferred bridge. The 2014 midterms were bound to bring change to Texas, with the retirement of then-governor Rick Perry setting off a wave of change down the ballot, even as it was generally assumed that Republicans would sweep the statewide offices again (as indeed they did). Burka was worried for Texas, as the election approached: worried about what he saw as an increasing unkindness along with an ideological hardening, at least on the right. I remember him worrying at an editorial meeting that then–attorney general Greg Abbott, who was running for governor, “has no sympathy”—a consideration that wasn’t widely shared at the time, but perhaps should have been. On Monday morning, hearing that Burka had passed, I wished we had worked harder to become the kind of Texas he believed we could be.

And of course, I cannot bite into a perfect piece of brisket without thinking of Burka’s perfect description: “like cookie dough.”

This story originally published online on August 15, 2022. An abbreviated version of it appeared in the October 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Great Paul Burka.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Obituaries

- Paul Burka