This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Long ago and far away, before Barbie met Ken and when G.I. Joe was a real guy, a summer day was about twenty hours long and a city block ran to the ends of the earth, according to our tiny bare feet. Refrigerated air was something that came out of the icebox when we went for the water jar. The concept of endlessly watching TV did not exist, as the screen was filled with an Indian chief’s head in a test-pattern target most of the day. Besides, there was only one TV on our block in Dallas, and it belonged to a snotty mama’s boy whose main claim to superiority was that he could make ten nicknames from his given name. In those days the object of life was to hit the ground as soon as possible after Post Toasties and stay out of adult sight until you slipped in for lunch, which you gobbled up before you made a fast break to avoid a nap. Even if you made good your escape, it was useless, because the other kids had usually been caught and stripped down to their skivvies, in the process being promised release if they would just close their eyes for ten minutes, a mysterious increment of time one pondered while falling asleep.

The great summer games didn’t begin until late afternoon because of the heat. Everyone knew that you couldn’t get polio when the heat-activated cicadas quit beeping their song. Sure, there were many popular games: dodgeball, where you tried to give concussions; “guns,” for dramatic cowboy and Indian death falls; stickball, for neighborhoods without front yards; and the wimpy games adults organized (musical chairs, goosey goosey gander). But the best games were the ones the kids created.

The game field was usually the front yard of a popular kid whose protective parents refused to let him run off into the night. In my case it was the yard of my next-door neighbor Mary Lou, with whom I would be smitten for years to come. Because of the baby boom, our block had more than twenty kids at any given moment—the perfect number for serious group participation, allowing for losses to measles, chicken pox, and various broken bones. The idea was to cram in as much playtime as possible before dinner, which was at dark. Adults were reluctant to break up games in progress, so our screams and hollers were raised for effect as darkness fell and tiny porch lights came on as visual dinner bells.

We took no official poll in deciding which game to play. Most themes lasted a few days, until we got bored. New games were brought home by kids who had gone to visit cousins in faraway places like Sioux City (which automatically made it an Indian game). The rules were always vague at first, allowing the presenter-inventor to win frequently—until the competition equalized and he was caught changing the rules. The game stabilized as the kids with overt zeal and driven gaming ability set the standards for winning. The pregame scenario usually went as follows:

Kid 1: “Let’s play swing the statue!”

Kid 2: “That’s a girl’s game!”

Kid 1: “You’re lying! My brother plays it all the time.”

Kid 3: “You don’t have to play, Ralph. I think I hear your mother calling!”

Kid 2: “She is not! I can play if I want!”

Kid 1: “Not in my yard. I’m the boss. You swing too hard anyway!”

“That’s because you’re a girl!” hollered Ralph as he walked to the center of the yard. “I’m the sculptor. I’ll swing first!” Nobody wanted another argument, and the game began.

My son, now 27, was a child of the sixties. In his yard-ape days, few of his games did not require the purchase of TV-touted items like Hot Wheels cars or electric ovens that produced rubber bugs. Because more parents had to work, children had no need to avoid parental control—and we hoped they would just stick around the house so they wouldn’t get hurt. Maybe costly toys and TV became surrogate baby-sitters and Barbie replaced Mom as a companion, conveying the message that exterior decoration has more meaning than interior development.

In protest of a silly Asian war, most of us steered our boys away from toys of violence. We recalled the results of World War II, glory messages that had our friends marching away to Vietnam with John Wayne zeal. Who would have guessed that their children would come to admire some bozo commando who makes money killing for dictators?

The children I’ve met lately are still pretty wonderful. Although I doubt that a game of swing the statue will diminish their love of mall life, I would like to see more interaction among children based on the notion that fun exists between their ears rather than in their billfolds. Maybe it’s too late for such idealism. A jar of lightning bugs holds little attraction in the face of terrorism, rotten politics, and serial killers. Maybe in my middle age I am simply longing for those naive days when I would come in from summer night games and my major concern was whether I’d be facing a plate of dreaded turnip greens, slimy okra, or gray fried liver.

Swing the Statue

This was a multiversion game with rules that changed from block to block. One person was the artist-sculptor (swinger). The others were clay (potential statues). Before the game, the players would search the yard for “artwork” by Cookie the dog or his friends. It was also a good idea to check for stickers. (I’m convinced that certain people on our block allowed the sticker weed to exist as a deterrent to children.)

Version 1: Artist set the theme. Before the artist began to swing the clay, he hollered, “Drunk farmers,” or “Clowns,” or the like. If he was creative, he suggested, “Vegetables,” “Zoo animals,” or “Howdy Doody.” The artist grabbed the hand of each player and spun him around until he achieved proper dizziness, at which time the artist let go. The clay then tried to fall in a suitable rendition of the theme. If the theme was vegetables, for example, the clay assumed the posture of celery or a green bean, then was called on to defend his artistic logic.

Version 2: Clay picked the theme. The clay was thrown into a posture of his choice, and the artist tried to guess its meaning. If he failed, either he became clay or all the players tried to guess the theme and the winner got to be the artist. The payoff was generally the laughs everyone got from silly themes. (Sometimes, however, another player would simply bully his way into the artist position if nobody guessed the theme.)

Version 3: The biggest kid tried to throw the clay so hard he didn’t get a chance to be anything but hurt—a favorite for secret vendettas.

One Potato, Two Potato

Being It is a child’s first lesson in the nature of life and the most humiliating experience of childhood. This phenomenon teaches that they who are powerful (i.e., they who are older and stronger) will call the shots on how the game is played, with the understanding that one will accept that reality or be banished to the porch steps in tears.

The means of selecting the It person had the older clique using the manipulative ritual of “one potato, two potato,” counting off the fists of players. The younger competitors seldom realized that the process was rigged: The counter generally knew that the It person was the fourth, eighth, or twelfth player as he smacked the hands of each in cadence with every word: “One potato, two potato, three potato, four/five potato, six potato, seven potato, more” (with the word “more,” the counter hit the hand of the It person). If the counter wanted to toy with the victim, he continued with “My mother told me to pick this one, but I was bad and picked this one. You’re It!” I’m convinced that the overachieving yuppie of today seeks power only to avoid being It.

Hide-and-Seek

Hide-and-seek was the big mama of summer activities. It offered so many variations that we didn’t get bored with it until after school started in September, when thoughts turned to Halloween. Each variation incorporated the It selection process and the emotional hammer of the hundred-count, the rite of passage that eliminated younger children (a given) while producing evidence of growth for the older kids by requiring the ability to count to one hundred. When younger siblings mastered the art, it was changed to counting by tens, a frustrating, abstract concept that sent them away, crying but dreaming of revenge—like leaving your aging parents to your care while they moved out of state.

Although kick the can, a favorite in which a can replaced the usual tree as home base, was always popular, our neighborhood after-dark favorite was Piggy Wants a Whistle. The kid who was It became the pig (I assume it was looking for slop) and counted to one hundred while the players hid. The pig was allowed ten calls of “Piggy wants a whistle!” and with each call all players were required to whistle, thus giving the pig a clue to the hiding places. Of course, the trick was to whistle as quietly as possible so you sounded farther away. At opportune times, players ran to home base and hollered the frustrating “Free!” accompanied by a humiliating laugh.

I invented a version of hide-and-seek that enjoyed a short success. It was a blockwide game in which teams of two placed four-by-five cards sporting the warning, “Posted Keep Out,” and the team name (Frank and Curtis) in their five favorite hiding places. Nobody else could use a spot marked by another team. When 24 kids were playing, 60 hiding places were eliminated, so you had to be good.

Tag

Tag was the game of the day. Most versions offered the older kids a chance to win easily, since the younger kids had no match for their longer legs. Many variations of tag were based on hide-and-seek. In wood tag, players were safe only when touching a tree, a picnic table, or a fence in open view. As the It stood ready to spring, the players would run from one safe position to another until they could reach home base.

Witch o’ Witch was a wonderfully scary night version of tag. The witch, a fine symbol of fear, thanks to Walt Disney, would creep among the ghosts, who were locked in their graves (positions) throughout the yard. In random order each ghost would ask, “Witch o’ witch, what time is it?” In the most horrible witch-cackle voice possible (Mary Lou used to make little children cry and go home), the witch would pick a time, such as “It’s eight o’clock.” As that pattern continued, tension grew. The witch would be ready for attack when she said, “Twelve o’clock midnight. Ghosts, go home!” Like frightened bunnies, all the ghosts tried to get away from the witch’s touch, which rendered them dead and out of the game, while running for the free spot called Church. Those tagged were doomed forever. This was a nice cheerful kiddie game, which probably accounts for the born-again movement.

Murder in the Dark

Another amusing game based on the delightful death motif, this pastime required as many slips of paper as there were players—at least a dozen. On most were written V for “victim,” while one sported the great M for “murderer.” This was one of the few times when being It was fun. The kid who was lucky enough to draw the M was secretly the dispatcher of his fellow playmates.

As total darkness ensued, each kid walked around, trying to avoid the dastardly killer, who had only to touch the victim to cause instant death and a retreat to the lit porch. The “dying” cries could be heard as the game progressed. The object was to guess who the killer was before he zapped you, which became easier if you were the last survivor and you hadn’t pulled the M.

Fox Across the River

Fox Across the River took advantage of the sidewalks in new housing developments. The sidewalk was the river, and the grass was the bank. In the river was the alligator-shark-octopus, the person who was It—generally the kid nobody liked, the smallest kid who would do anything to play with the older kids, or the kid guaranteed to cry. On either side of the river stood the foxes. When the alligator hollered, “Fox across the river,” the foxes had to jump across the river without being eaten (tagged) by the alligator. If a fox was touched, he became the alligator. The game progressed until the alligator, if he couldn’t catch a fox, began to cry or until a fox slipped on the grass or concrete and hurt something (and crying usually brought adults).

Red Light, Green Light

This was a sped-up version of Mother May I. The leader, usually the person who suggested the game and loved power, became the traffic cop. At the announcement “Green light!” each kid in two lanes began to walk forward, toward the porch steps, where the cop stood. “Red light!” required an instant stop. Anyone moving got a ticket and had to drop out of the game. The object was to be the last car still in traffic or the first to touch the steps. The game became heated when the cop said, “Red light green light red light,” with no pause for punctuation, or when he reversed the order by saying, “Green light,” first. The game usually came to a halt when the cop forgot what light he was on and one of the cars said, “I’m not playing anymore, ’cause you cheat!”

The Lightning-Bug Raid

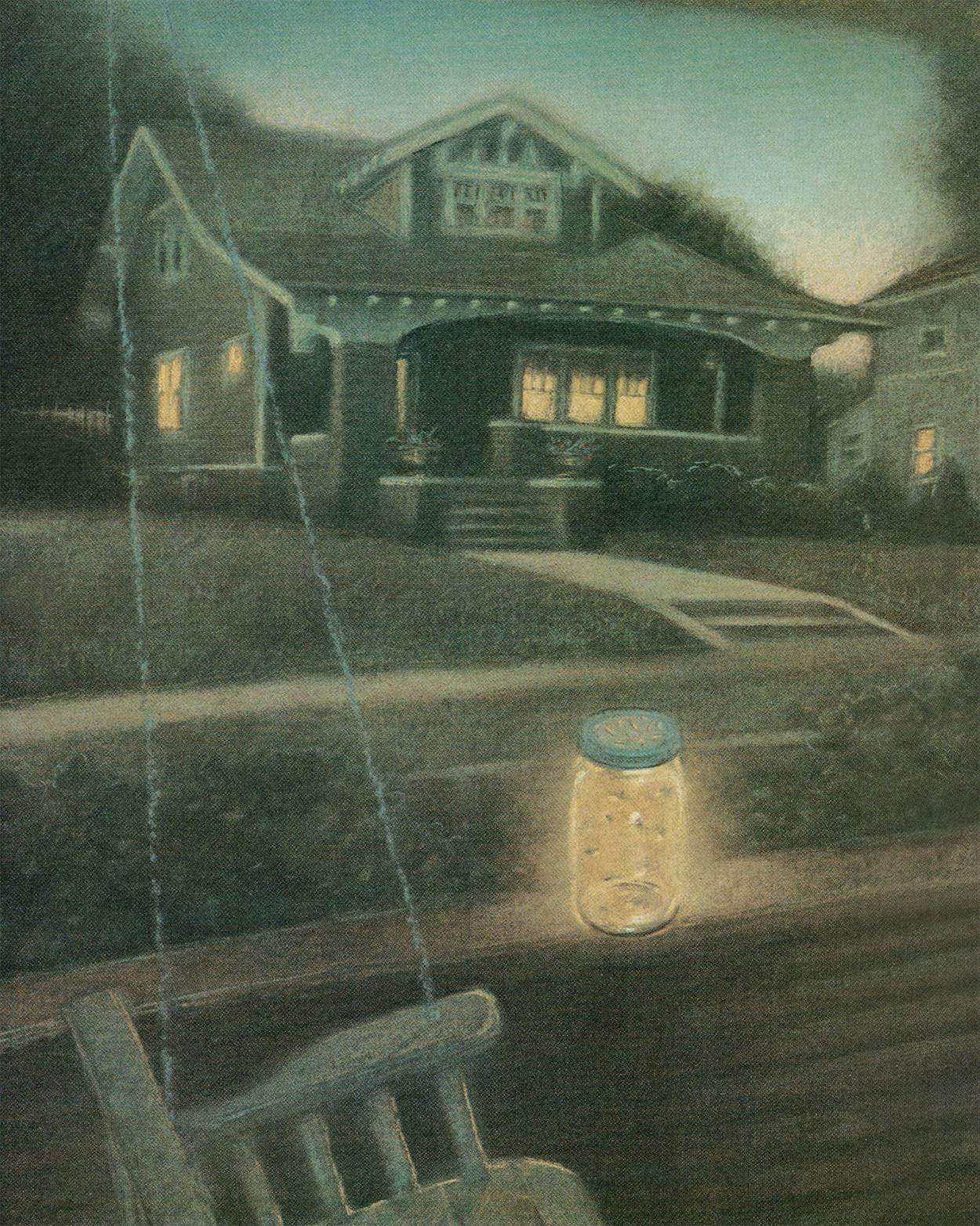

Fireflies, lightning bugs, or whatever you call them are nature’s voodoo. There is simply no logical excuse for a bug that can light up its butt. It seems as if more lightning bugs existed in the old days (or maybe my eyes and hands were smaller). After grabbing them out of the air or from leaves, we would stuff them in a jar with holes in the lid to make a lantern. If we didn’t let them out before we went to bed, we’d find them dead in the morning. The little twinkles meant fairies could exist, along with ghosts and people with no heads. The initial object of the game was to see who could collect the most bugs, but that usually gave way to torturing them and smashing them on our skin, where they continued to glow. Generally, parents or big kids came to the bugs’ rescue: “How would you like to be trapped in a jar by a giant who wanted to smash your guts out?” We’d turn them loose.

George Toomer is a freelance writer who lives in Dallas.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Dallas