This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In ways that were subtle and sometimes not so subtle, the perfidious Texas economy changed the lives of nearly everyone. In this section you’ll meet some Texans who coped. A man who had made a fortune drilling for oil drilled instead for water—and made another fortune. A teacher looking for a more satisfying life took a roller coaster ride and ended up back where he started. A guilt-ridden liberal-turned-capitalist found herself alone on the wrong side of the tracks, but the experience was exciting and she lived to tell about it. Have we come full circle? No one can say, but the linear voyage has been sobering and we’re all a little older and hopefully wiser.

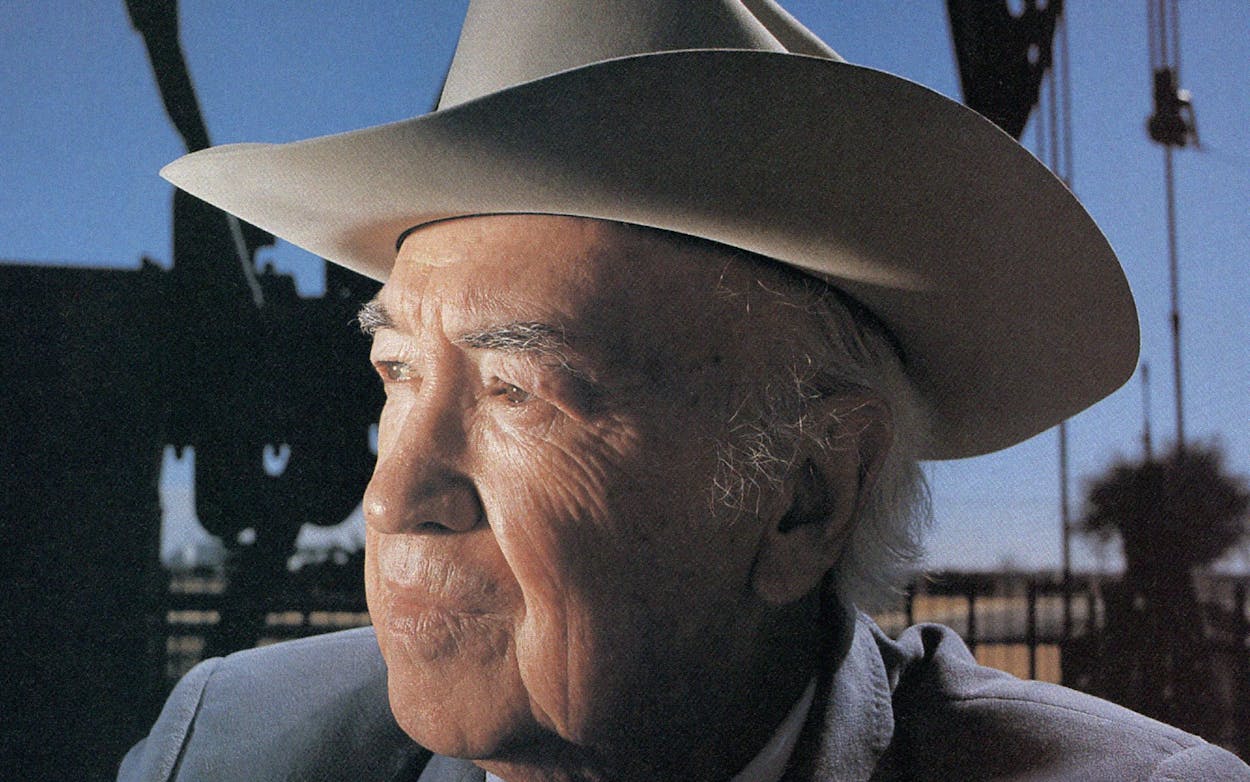

Hank Avery

Entrepreneur

Midland

When he was the mayor of Midland, Avery fled the lawsuit that resulted in the historic U.S. Supreme Court decision affirming the principle of one man, one vote. Formerly an oilman, Avery, 67, now locates people who are owed royalties by oil companies. He is a tall man with thinning gray hair, and he wears a navy Ultra Suede blazer, a ring with six large diamonds, and a watch with a rugged gold-nugget effect. When oil took a dive in the early eighties, Avery nimbly adjusted and found a new way to make a living.

You had an income of twelve, fifteen, twenty thousand dollars a month, and suddenly the price of oil went down the drain and you’re making one third of that. You let the maid go, start mowing your own lawn and doing your own dishes and windows. The best way to judge a community: Don’t talk to the chamber of commerce; make friends out of the people in the U-Haul business. They could have told you that people were leaving town. Construction ceased. Things had been looking great, then all of a sudden, bang! Like a dead pigeon.

I’ve always been the sort of guy that thought you could make money if you find a need, and I read in the paper that Duval Sulphur, which is owned by Pennzoil, needed water. So I knew where there was a water field and told a friend at a bank, and the next day there was a fellow from Duval in my office, saying, “You got a water field?” So I sold that water field. Then I said, “If you’re interested in another water field, I’ve got one closer to your plant.” Next day they were in my office with a $50,000 check for an option. With the $50,000, I drilled twelve wells and sold them to Duval for $350,000. Took me about six months.

Then I said, “Well, if you guys ever need more water, let me know.” I told them where it was, west of Toyah, which is west of Pecos, and the next day they had another $50,000 on my desk. Well, I went out and proved up that water field. At the time I didn’t know there was a sulphur deposit up in Culberson County, but this water is now going to the sulphur plant, and they’re producing five thousand tons a day out there with the water that I sold them west of Toyah. I think I got a half million for that field.

Then I said, “If you guys really ever want some more, I have a prime, prime water field.” Next day they were in my office again with another $50,000. So I went out and drilled 26 wells and bought a 25,000-acre ranch; then I agreed to sell the water rights under the 25,000 acres to Duval and kept the surface and mineral rights. Finally, we’re down in Houston closing the deal late one afternoon. I’m saying, “You guys have to drive me to the airport because I need to be back home in Midland.” And they said, “Avery, if we don’t exercise our option, what will you do?” And I said, “I’ve already sold it.” The biggest poker game I ever played. They left the room and came back and said, “Yeah, we’ll exercise our option.” So I sold the ranch for a million-two and then sold the surface and mineral rights for another million-six, I think it was.

But then I said, “Wait a minute, before I leave, how did you all find all of that sulphur out in Culberson County?” And they said, “We sent a geologist out to Midland, and he went over to the Midland library and looked up ‘sulphur,’ and there it was, all written up that there was sulphur out in Culberson and Pecos counties.”

And about that time the president of Duval Sulphur says, “Hank, let me ask you something. You’ve sold us four water fields so far—and we don’t need any more, incidentally—but how did you find all that water out in West Texas?” And I said, “You won’t believe this, but I found it over at the Midland library. You knew how to spell ‘sulphur,’ and I knew how to spell ‘water.’ ”

Let me say one thing, and this is the truth: If you ever want to keep something a secret, just publish it and put it in the Midland library and it will be forever a secret. Until somebody wants to really make some money.

Eric Taube

Bankruptcy Lawyer

Austin

Educated at Vanderbilt and the University of Houston law school, Taube, 32, recently made partner at the law firm of Liddell, Sapp, Zivley, Hill, and LaBoon. He and his wife, Judy, moved from Houston to Austin in 1986; they have two children. A robust man with a full beard and shaggy, curly hair, Taube surveys the world through tinted glasses. In his fourteenth-floor office overlooking downtown Austin, he talks about Texas from the perspective of a Brooklyn-born Jew who arrived here at precisely the right time.

In 1979, when I got out of Vanderbilt, there were a lot of people going to Texas. I mean, that was where the jobs were. A bunch of my fraternity brothers were from Texas—the most colorful ones in particular were from Wichita Falls. A friend got me interested in the idea of going to the University of Houston. It was a good, cheap place for me to go to law school. We went down to Houston one weekend after I had made my application to the law school, and Judy got about five job offers in about ten minutes. I mean, it was just incredible what was going on.

Well, my dad’s a lawyer, and he had been doing some work in the bankruptcy area up in New York. I made law review, and I needed a topic to write on, so my dad suggested a particular topic in the bankruptcy area. It sounded kind of interesting. So I wrote the article, and it was extremely well received. It was published, and I won an award for it. Since it had a code, this aspect of law was easy to research and easy to understand. And the law had just been completely rewritten in 1978, so even the old guys who had been practicing bankruptcy law for years didn’t know any more about it than I did.

The problem in the late seventies was that the Texas economy was booming. I mean, there weren’t any bankruptcies. People didn’t hold you in reverence because you were a great bankruptcy lawyer. They tolerated you, the way they tolerate good undertakers. But as I got out of law school in ’83, all of a sudden bankruptcy was the hottest thing going. In fact, I had a hearing that I had to take care of the first day I was licensed!

At first I didn’t get a sense of panic. If I could characterize it, I’d say people were asleep at the switch. I remember going into a bank in Houston, not one of the major banks but a good B-plus second-tier bank. My client and I went to what used to be the energy floor. You could have set off a bomb there, and it wouldn’t have hurt anybody. The whole floor was empty.

After a while it got really scary to watch. There was this old-line Houston oil-and-gas developer whose company was in serious, serious trouble in early ’86. I watched this guy deteriorate both emotionally and physically. Clients were calling me up at four o’clock in the morning, just to talk. It was kind of like being a doctor. It was something very, very important to them. It was important to me too, but not at four o’clock in the morning. It got to the point I had to change my phone number.

Judy and I moved to Austin because this is where we wanted to raise our family. I love living in Texas. I love living in Austin—I want to be here the rest of my life. But I don’t consider myself a Texan, and do you know why? Because of the people who make such a point out of being Texans. Professional Texans, you might call them. Guys with the “Native Texan” bumper stickers. Good for them. I don’t care about that. I’m just as much a part of this community as anybody who’s grown up here. Maybe more so, because I got a lot more invested in it. I didn’t just happen to end up here. I came here. I wanted to live here.

Mary Burton DeMotte

Oil Trader

Houston

DeMotte is chairman of the board of DeMotte Energy, which she started when her oilman husband, Paul, died in the seventies. Her father, brother, and other relatives were also oilmen. Married at sixteen, DeMotte persuaded her husband to put her through college; she has a master’s degree from the University of Houston. A flamboyant woman with flame-red hair, green eyeglasses, and a taste for frilly parasols, she declines to reveal her age. But DeMotte moves easily in the male-dominated world of oil and finance while managing to swim in Houston’s social currents.

Paul and I had been married for more than 25 years and didn’t have any children; consequently, I traveled with him a lot and learned about the exploration part of the oil business. You’d get information that a certain area looked promising and get in your car and survey the location and find out who had not leased their land. As a general rule, there was always a holdout. So you’d go door to door looking for them, and I’d get the typewriter out and type up the lease, sitting in the landowner’s house, and then run out and find a notary. They still do that in boom areas. A lot of oilmen are over in Lake Charles, Louisiana, right now, knocking on doors.

We lived really high on the social merry-go-round. Paul had eight tuxedos, all kinds. They’re wearing them all over River Oaks today! We belonged to six dance clubs, and each one had three dances a year. We lived at the Regency on Westheimer—I’m still there—and we entertained all the time. He used to say, “If it starts raining, Mary will decide to have a rain party tonight.” He would never ask who was on the guest list; he didn’t care one way or another. But he liked to cook, and he could mix all the drinks. He was a great host.

I still like the social circuit, but that’s secondary in my life. I like to make money. I like the achievement of making a deal and seeing it come together. Maybe once every two weeks I go to lunch with my lady friends, but I’m just not into that. I don’t have time to go to these style show luncheons at River Oaks with the ladies. Instead, I’m down at the Houston Club, the Petroleum Club, or Otto’s Bar-B-Q—where, incidentally, there’s a picture of me and Gerald Ford—having lunch with the captains of industry. Ninety percent of the deals I do are generated through lunches with oilmen.

I’m what you call an oil trader. Not trading in products, understand, trading in deals. I have a friend, for example, who owns half the minerals on a three-thousand-acre ranch, and my geologist tells me this ranch has very good gas prospects. Well, my friend can’t get the man who owns the other half of the minerals to sell or deal. But see, my husband was very well respected in the oil business and a lot of that respect transferred to me, so I contact the man and he agrees to sell to me. Then I turn around and resell them to my friend. If the deal goes through, I make some money. And in the meantime, if it’s a good gas prospect, which my geologist thinks it is, then I’ll get my friend to lease the land back to me and in turn I’ll sell it to some of these oilmen I know. You see what I mean? There are a lot of different ways to make money in the oil business.

I’m not a woman’s libber. I’ve always thought that men made the rules and if the woman was ambitious and smart, she’d live within those rules. If men like you and think you’re smart, they’ll help you. They’re not going to let you run wide open and step on them and keep going. But they take a lot of pleasure doing something for a woman if the woman shows respect. For example, I’m on the Houston Producers Forum, which is a group of young oilmen, all highly successful, dynamite young fellows—35, 40 years old. And it’s a real compliment. I’m probably the oldest one there, ’cause I really run around with their parents. Then I’m on the executive board of the Texas Independent Producers, the only Houston woman they’ve ever had on the board. This is the highest compliment I’ve ever been paid.

Ron Burton

Sales Representative

Dallas

Burton, 42, an architectural specialist with a window manufacturer, has traveled the cycle of the typical Texas baby boomer. A dropout from his original career as a schoolteacher, Burton worked as a mechanic, moved west in search of adventure, returned to seek his fortune in the Austin building boom, went bankrupt, and finally settled in Dallas, near the place where he started. Dressed in a suit and tie, his hair combed back in middle-age conformity, Burton sips an after-work cocktail and talks about his odyssey.

I was teaching at a junior high in Rockwall in 1976, when I got the bug to move out west. We had one child, and we’d been out west quite a few times on vacation, driving out, and we really liked it. So we decided we wanted to move out there. Just quit our jobs, sold ’most everything we had, bought a camper, and took off. In retrospect, I don’t know what I was looking for.

Finally got up to Missoula, Montana, and decided we’d about done all the traveling we could do, so we started back south. Got back to a place in Utah, nice little Mormon town. Camped in one of these campgrounds, under the trailer. We’d been out about seven and a half weeks, and about ten o’clock that night I just couldn’t stay there anymore; I had to come back south. So I told my wife, I said, “I gotta go. If you can sleep, I can drive.” So we hooked ’em, and I drove to Durango that night. Took about ten hours.

Our daughter was in the second grade, and we were obviously concerned about school, so we moved to Austin, where my brother lived. We lived in our trailer in my brother’s driveway the rest of the summer, then found a place to rent. My wife was a legal secretary and got a job with a court-reporting firm. Pretty grim period of time. I’d always worked on cars when I was growing up, so I decided I’d better go into mechanics, and I enrolled at Austin Community College in an auto-mechanics training course. Worked at two or three jobs at night and went to school during the day. After I graduated I got a job at the Lincoln-Mercury downtown, and not too long after that, I got an opportunity to go to Colorado with a friend to deliver a car. This guy and I had met through our daughters; they were both in Girl Scouts together.

Anyway, we drove to Durango, and while I was there I decided to look for a job. I walked into a Ford dealership, and they hired me on the spot. That was about December 7, 1977. I rented a place, then drove back to Denver, and when I got to Stapleton Airport, I called my wife and said, “You still want to move to Colorado?” She said, “Yes, when?” and I said, “Two weeks.”

We drove out of Austin on December 26, and got to Durango about two days later, in the driving snow. We didn’t know the first thing about driving in the snow. I’d rented a place about twenty miles out of town, which was a mistake, though at the time I rented it, there wasn’t any snow on the ground, and twenty miles to a Texan is no distance at all.

Well, we rocked along until about May, and then my wife got an opportunity to go back and work for an attorney in Austin. So we went back, hobbled back on a wing and a prayer, just as broke as we could be. In the meantime, this friend who had taken me to Durango, the one whose daughter was in the Girl Scouts with my daughter, had gone into the building business. He’d just up and quit his job one day at the IRS and started doing his thing. The real boom hadn’t hit, but things were pretty good. Money was loose and was starting to get looser. He had been after me for about three or four months to come work for him. I knew cars and I was a teacher, but that was all. I told him, “I don’t know anything about building,” and he said, “Oh, well, that’s easy. I need someone who can manage projects.” So I said, “Well, if you’re willing for me to learn on the job.” So I went to work for him.

It was about a year later when the Austin real estate market really took off. Real estate was feeding off the oil craze at first, then it started feeding off itself, like a big school of sharks. People who had no experience were getting in the business—airline pilots, plumbers. Anyway, we started doing spec houses, got into the $250,000 range, mostly in Northwest Hills. He specialized in California-style hillside projects, homes that most contractors thought were unbuildable.

First project I did for him was an apartment complex around UT, a real hot property. We finished on a Friday and closed a sale on the project the same day. Made a lot of money, mostly on a long-term note, which he used to get a cash flow to get his business going even better, to build larger homes. We rocked on for another three years and ended up with a piece of property out in West Lake, seven or eight lots near Wild Basin. Meantime, we got a contract to build a very big house, and we also started developing a large project down in this cul-de-sac in West Lake. It was spec, and it was going to cost $1 million. While I was building in West Lake, my friend was developing a property on Sixth Street. While that project was under way the bust hit.

Within about three months, the banks pulled their horns in completely—just stopped loaning money. We couldn’t get financing for the Sixth Street project, and all this time I’m still doing houses out in West Lake. Things got pretty bad. We got semi-stopped by the bank on the big spec jobs. During that period of time, I decided that maybe I ought to try to look for something else.

In the summer of ’85 I decided that maybe the best thing to do was start my own construction company. I got a call from an architect looking for a contractor to build a house on Mount Bonnell for some people out of Denmark, some bigwig from Chevron who wanted to retire to Austin, where his son lived. So I quit the developer, got my attorney to draw up papers to incorporate, and went out on my own. Then I got another contract to build a big house in the Estates at Barton Creek. We were ecstatic! Here we were, brand-new business, and we had two big houses. Both turned out real well and we made some money and other things came along.

But I was getting a little nervous. Everyone was pulling out of the business. Things were falling apart. I had gotten a large renovation in the Estates, and by the time I finished, the guy went bankrupt, owing me a lot of money. We rocked along as best as we could but just couldn’t stay in business, and then I sat at home for about six months with one little project going and nothing much to do. Pretty depressing. Finally filed bankruptcy; couldn’t do much more than we’d done. Got stiffed by not only clients, but the client that owed us money had borrowed money from the bank I was doing business with to buy the house, and the bank ended up with the house back, which it didn’t want, and I, of course, owed it money on loans for the business. It was all kind of a mess at the end. So we ended up moving back to Dallas, which was where we’re from originally, and here we are.

I was devastated. Felt like a failure. You analyze it, and you think, “Hell, I didn’t do anything wrong.” When we were in business, my wife and I did everything aboveboard, did everything the way it was supposed to be done. In retrospect, I looked back on Austin and saw what had been happening. It was nuts, those eight years I spent in Austin in real estate. There were just no rules. At the height of the boom you could get money to do almost anything in construction. You’d be appalled if you knew what your banker was doing. You go to lunch with an architect, and he tells you things are slowing down, and well, you don’t go to lunch with this guy anymore. Nobody wants to hear the bad news.

My dad used to describe the Depression, and I never thought that would happen to me. We’d never saved a bunch of money for a rainy day; I mean, we just didn’t do that. Most people don’t. I’m 42 years old, and I see the advantage of that now, but I didn’t at the time. You know, our business was gonna be our savior to send our child to college and all that stuff, and all our dreams just shattered. It was devastating.

So I’m wearing a lot of hats these days. I work for Marvin Windows of Minnesota. This is a local distributor based out of Lubbock, and I’m the architectural rep, which means I call on architects, trying to get our windows specified in projects. I also do promo work, luncheons, take architects to the plant, to trade shows, all that stuff. I do a little construction consulting, helping people with their residential projects. Yes, the real estate and construction business is starting to come back in Texas—who knows for how long?

You know that guy I worked with for eight years in Austin? We parted on less than amicable terms, but I’ll tell you one thing: He’d climb out on that limb every day and start sawing, and the trick was to get back before the limb fell off. And he did it every day. You don’t find that sort of courage in too many places, but you do find it in Texas.

Joan Yamini

Associate Psychologist

Austin

Born in Dallas, Yamini came to Austin to attend UT in 1974. During ten years of undergraduate study, Yamini made extra money by hiring out as a maid and later started a maid service, which, during the boom days, grossed $70,000 a year. Since gaining a master’s degree in educational psychology in 1986 from Southwest Texas State, Yamini, 34, has scaled down her housecleaning business (it now grosses about $30,000 a year) and works as an associate school psychologist. Unmarried, she is an attractive woman with brown hair and an unabashed collection of liberal guilts, which she is able to laugh about. Seated in the book-strewn living room of her apartment in the Hyde Park neighborhood, Yamini recalls her family and talks about the incongruity of her liberal views and her career as a hard-nosed capitalist.

My mother’s father was an Italian immigrant, born just south of Naples, and he just recently died at age 99. So my mom’s first generation. My father’s father was Syrian, and he immigrated from Nazareth, Palestine. My identification is really more with the Italian side. But a funny story: I have a very old friend named Jan who’s a psychologist and doctor, and one day in a conversation we discovered that her Russian-Jewish grandfather had ended up in Sweetwater, Texas, with a dry goods store directly across the street and in competition with my Syrian grandfather.

In spite of pretty conservative, squarely middle-class parents, I developed liberal ideas in high school and transferred to a new school called Skyline, which was a pilot project. I was half in the music department, half in psychology. And I’m quite sure to this day that if my parents had realized the huge change in me politically, they never, never would have encouraged me. We cancel each other out in every election.

In ’77, to earn some extra money, I put an ad in the newspaper offering to do some housecleaning, and suddenly my phone was ringing off the wall. This was a time before yuppies, kind of a burgeoning time of women going to work. Politically, it was a big issue. There were more and more two-income families, and the heart of the matter was, you know, who is going to clean the toilet? I was working in the children’s unit of the state hospital with these other child-care workers who were bright and energetic and committed and honest—well, at least honest—and I’d say, “I have a person’s house that needs cleaning, and I’ll pay you five dollars an hour and charge them six and keep one for myself.” So I was a broker. Business grew and grew, and I bought an answering machine.

During the economic boom in the early eighties, I expanded into the commercial area as well as the residential. I had accounts with Wylie’s, the Paradise, the 606, the Oyster Bar, all kinds of hot restaurants and bars. I hired a foreman and a crew. And it was an eye-opener, I mean, a different class of people willing to work that time of night. Mostly men, because women shied away from some aspects—you know, the things you had to clean up at three o’clock in the morning. It was gross! Sometimes I would have to drive over to East Austin at four in the morning to pick up guys, you know, who were four times as big as I was and four times less educated and maybe less moral and take them down to these bars and supervise their cleaning. I tried to tell myself that these are human beings just like I am and there was no reason to be scared. But I was petrified. And still, ethically, I was unwilling to acknowledge that I was a white, middle-class female, young, unprotected, in low-economic, high-crime areas with men who were, you know . . .

There was this one guy who ripped me off for the better part of a year. He was a young black man. And I was so unwilling to deal with my racial guilt that I think I overlooked his, ah, sociopathic tendencies. And when I did confront him, he was real mean to me. He intimidated me. I think he could see the white guilt written all over my face. But it was all somehow very exciting. I don’t know how I got through it, but I did.

David Griffin

Urban Consultant

Plano

Raised in Paris, Texas, Griffin, 34, majored in government at East Texas State and worked at several jobs, including a three-year stint as a high school teacher in Oklahoma, where his new wife and her three children by a previous marriage lived. In 1971 Griffin became the city manager of Plano, a town whose phenomenal growth became a paradigm of the Texas boom. In 1983, about the time that the economy went belly-up, he made the transition from the public to the private sector. His clients include 23 to 30 cities. A tall man with brown hair and sandy-colored eyebrows and moustache, Griffin sits in his well-appointed office and recalls the extraordinary urban and social changes in his lifetime.

Plano had already experienced a lot of residential growth by the time I got here. It had gone from about 3,000 to 17,000, and it no longer looked like a little country town. Plano had a lot of reasons to grow, the Central Expressway and its easy access to Dallas being one. Also, housing was less expensive, and it wasn’t a part of the Dallas school system, whose problems were as acute then as they are now. People saw Plano as a haven to get away from the strife of integration. Yes, it was a classic example of white flight. But to its credit, Plano developed a very good school system. Over the years I’ve talked to many families who moved here and asked them what brought them to Plano as opposed to Carrollton or De Soto or Garland, and it’s the schools.

Now, we were attracting immigration. It wasn’t so much white flight out of Dallas as it was people coming from other parts of the United States. Plano became the nesting ground for the migratory American executive. These folks would move in, stay a few years, and leave. Beginning in the eighties, this trend of moving people around in the corporate world stopped.

Plano was a place where people slept and kids went to school and that was about it. There wasn’t much cohesiveness. High school football is what finally brought people together. People rallied around that. We did something else which, in retrospect, brought people together. The school system and the city joined forces to provide recreational settings for people. What we did, the community’s master plan, had major thoroughfares that created one-mile grids, and we put elementary schools in the middle of the grids so that children wouldn’t have to walk across major thoroughfares to get to school. Then we would go in and buy five or six acres of parkland directly adjacent to the school, jointly developing recreation facilities in the school gym; and the city would finance evening classes for adults, using city personnel.

But the most remarkable and dramatic change I’ve seen in my lifetime—including technological advances—is the way minorities are treated today. When I was twelve or thirteen, black people couldn’t drink out of the same fountain, eat at the same table, or use the same rest room. For our society to have changed so much in one generation is absolutely remarkable. There was a black woman who came to our house occasionally and would help my mother do canning and stuff like that. And think about this a minute: Carrie was educated, a teacher in the black community, but she had to work for my mother for extra income. She and my mother loved each other dearly, but Mother would never have considered having Carrie to a social function, nor would Carrie have considered having Mother to a social function. Isn’t that a shame? These people loved each other, but they couldn’t express that love in that society.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics