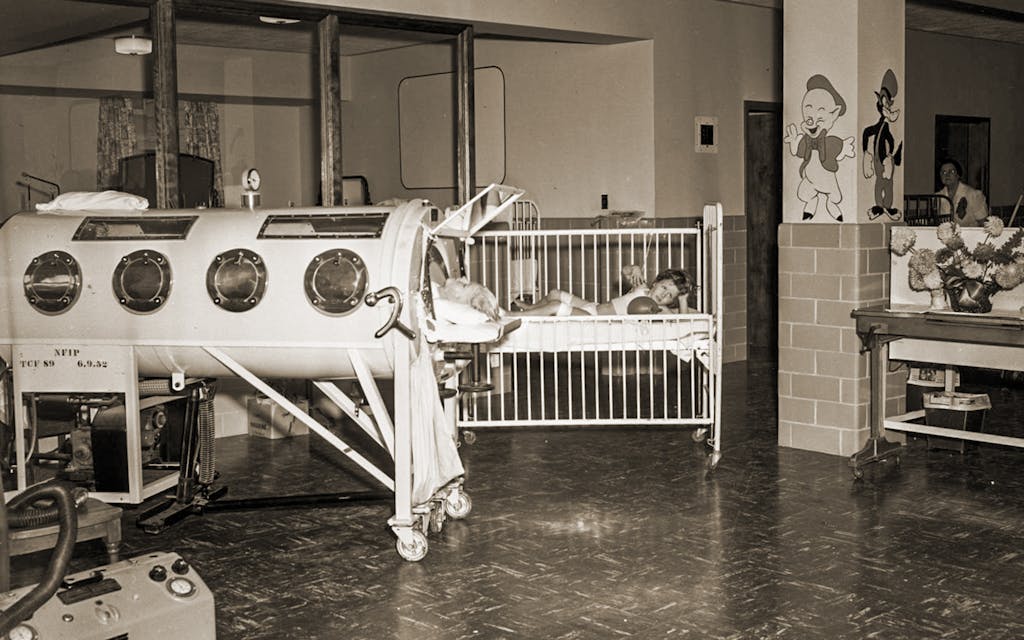

It’s easy to forget today, as we battle a different pandemic, but polio terrified Americans throughout the first half of the twentieth century. At the height of the epidemic, in 1952, more than 21,000 people, most of them children, were paralyzed from the disease. More than three thousand Americans died from polio that year. Life during that long-ago outbreak now seems eerily familiar. “You had to stay away from crowds, just like today,” remembers David Oshinsky, who grew up in the fifties and later wrote Polio: An American Story. “You couldn’t go swimming, bowling, or to the movies.” A constant, low-level anxiety was the norm; Oshinsky recalls that his parents gave him a rudimentary polio test every few days. “Could I put my chin to my chest? Could I touch my toes? The slightest sense that you were ill would bring a real feeling of panic.”

From the 1940s through the mid-1950s, outbreaks spiked every summer, partly because the virus thrived in the heat. Harris County was especially hard-hit in 1952, as the disease spread across Texas. A New York Times article in June of that year reported that medical facilities in North Texas were running out of space to care for polio patients. “Texas experienced an exceptionally high rate of polio incidence,” Heather Green Wooten, author of The Polio Years in Texas, told the Houston Chronicle. “Each summer, from Amarillo to Corpus Christi, from El Paso to Tyler, all communities, both urban and rural, were fearful of where polio might strike next.”

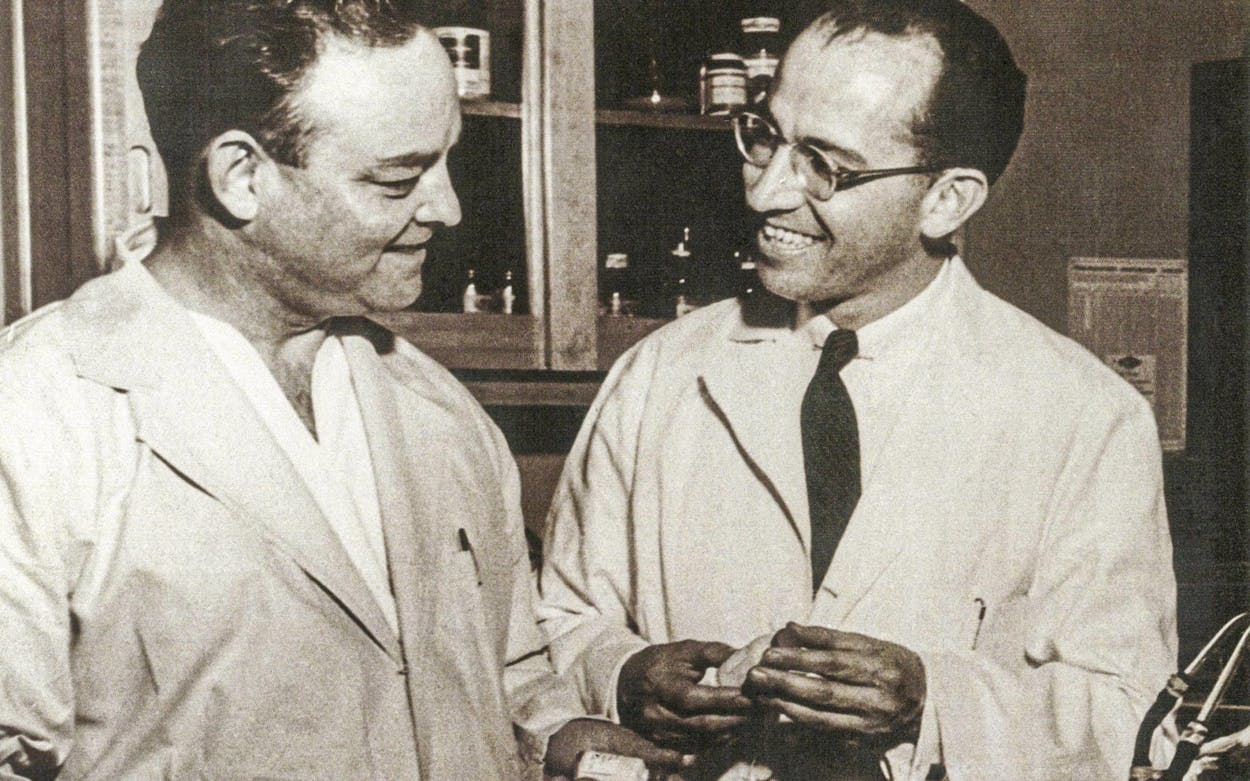

It was cause for celebration, then, when on January 27, 1953, the front pages of newspapers across the nation announced that Dr. Jonas Salk and his research team at the University of Pittsburgh had developed a promising polio vaccine. A week later, Byron Bennett, Salk’s 45-year-old chief technician, mailed a letter from Pittsburgh to his hometown of Mount Vernon, Texas. “Dear Mama,” it began, with slanted cursive letters in blue ink. “You have probably heard about ‘Dr. Jonas E. Salk and his co-workers’ producing a polio vaccine. I am one of the three co-workers—and we are disappointed about not being mentioned by name,” he wrote.

The polio vaccine is one of the biggest success stories in scientific history: the U.S. eradicated the disease by 1979, and with nearly three billion children vaccinated worldwide, the global fight is nearly won too. Yet Bennett is still almost entirely unknown; to his and his family’s great disappointment, he never got much recognition for the seven years he dedicated to working on the vaccine. Bennett’s story is an uncomfortable one. It raises difficult questions about who should get credit for scientific breakthroughs, which are almost always achieved by collaborative teams, not star researchers working in isolation. Within five years of the 1953 announcement, children across the country would be inoculated, Salk would be a household name, and Bennett would be dead.

For 21 years, a dented, camel-brown suitcase—eleven by sixteen inches in size—gathered dust in the attic of Byron Bennett’s sister’s house in Mount Vernon, about halfway between Dallas and Texarkana. I regularly travel there to visit with a local historian named B. F. Hicks. While we walked around a cemetery in November, Hicks pointed out Bennett’s grave marker, a nondescript tombstone not much larger than the suitcase. He mentioned he had a “trunk” of things relating to Bennett.

After Bennett’s sister died in 1978, an antiques dealer acquired the suitcase. He didn’t find much of value inside and sold it to Hicks for $50 a few years ago. Hicks kept it in a storage closet, but never took the time to fully investigate what was inside. Knowing I am a journalist, he gave it to me in case it was a story worth telling. When I returned to Dallas that night, I opened the time capsule.

The buckles were rusted and stuck a bit, but they popped open with a flick of the wrist. On top, old receipts saved for tax purposes were rolled and secured with a rubber band. Deeds for acreage around northeast Texas were folded into thirds. Then: a death certificate for Byron Louis Bennett. It was an original, with a Pennsylvania seal pressed in June 1957.

Under it were postcards and letters from Bennett, including the 1953 note to his mother. The contents of the suitcase relay the untold story of Bennett, who, despite working closely with Salk for nine years, is scarcely mentioned in books about the famed virologist. In Richard Carter’s 1966 Breakthrough, Bennett is described as “a hard-drinking, highly emotional, self-educated Texan.” This was true, but to the person who first stored that suitcase away, Bennett was much more.

“I feel that someday, [maybe] not in our lifetime, there will be something written,” his wife, Bobbie, wrote after his death, “and so I am saving all the clippings I have and all the important letters.”

Bennett was born in Hopewell, just northwest of Paris, Texas, in 1907. He joined the Navy when he was a junior at Mount Vernon High School; after graduation, he started his unconventional scientific career as a technician at a military medical laboratory in New England. In 1928, he left the Navy and enrolled at Harvard University with the intent to study medicine. Instead, he joined a Harvard medical expedition in Mexico. One expedition turned into nine. He worked in Guatemala, Peru, and the Congo as an all-around technician in the battle against Oroya fever, a blood infection, and onchocerciasis, a fly-borne disease that blinds victims. Then America was drawn into another world war, prompting Bennett to join the Army Medical Service Corps on December 7, 1941. His role in the Sanitary Corps in Italy and Egypt was to help control typhus fever outbreaks that were hampering the staging of American and Allied troops. Through field studies, he helped determine that locals had been using the same needle up to seven times when giving vaccinations. Bennett earned a medal for his work against the disease. He sent a letter to his parents on February 21, 1945, with photos from the medal ceremony and a paragraph of information in case they wanted it printed in the local paper. “This is the straight dope as the powers that be have recorded it,” he wrote, before signing off the way he would end all future letters: “Heaps of love, Byron.”

He never earned a college degree. After Bennett retired from the Army, Jonas Salk hired the then-39-year-old to join his new lab at the University of Pittsburgh. Salk and Bennett started the same day in October 1947 and shared a one-room office. Six weeks later, a deliveryman arrived with six monkeys, which the scientists used to study influenza.

Bennett held his boss in high esteem. Though Bennett was struggling with alcoholism and sometimes missed work because of it, Salk kept him on. Bennett had “one of the sharpest scientific minds and the best set of natural lab skills Salk had ever encountered,” Jeffrey Kluger writes in his book Splendid Solution. Salk also kept him in check. “Salk was Bennett’s joy,” a coworker said in Breakthrough. “His devotion to Jonas was positively doglike. Jonas held him together with spit and chewing gum, making him feel important—which he was—and somehow managing to keep the drinking within tolerable limits.”

The lab’s focus shifted from the flu to polio in 1949, when the University of Pittsburgh received a $148,000 grant from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP), known today as the March of Dimes. Salk used part of the money to hire a handful of others to fill the empty lab, including Julius Youngner and James Lewis. This core team of four was a motley crew: Youngner had worked on the Manhattan Project, and Lewis was a bacteriologist who had worked for several pharmaceutical companies. Bennett was a major in the Army, and Salk addressed him as such. He made sure the rest of the members of the lab did so as well. “All of these people had their particular strengths,” Dr. Peter Salk tells Texas Monthly of his father’s hires. “It didn’t matter what their degrees were.”

The monkeys arrived weekly from India and the Philippines. In all, the researchers experimented on more than 15,000 of them. Bennett’s position as chief technician included overseeing all the equipment, but he is also identified in newspaper accounts as a research associate. A Pittsburgh Press article said Bennett “played a leading role” in the development of the vaccine. He processed blood and tissue samples from the animals and logged the data before the team of four analyzed it. His final job was to ensure that when the vaccine was prepared, the virus that was included in it was properly bathed in formaldehyde. He had to verify the virus was actually dead before the vaccine was injected into the monkeys and, eventually, children.

The NFIP poured $2 million into the Pitt team’s work. As with Operation Warp Speed in 2020, numerous scientists and labs were racing to develop a vaccine. Members of Salk’s team worked six days a week and often came in on Sundays as well. They felt a sense of national duty.

“It was a very frightening period that came at a time when the baby boom was happening, and taking care of the children was the center of everyone’s life in America,” Oshinsky says. “And here came this really insidious disease that focused essentially on children. Fighting polio became America’s crusade.”

After all those celebratory headlines about a promising breakthrough in January 1953, it was still another two years before the vaccine was declared safe and effective. Researchers still had to conduct large-scale trials. Salk took to the radio in March 1953 to explain that the vaccine wasn’t coming right away and where his team was in its process. After that, it was dubbed the “Salk vaccine.”

“That had absolutely nothing to do with my father,” Peter Salk says. “It was not his desire. He wanted it to be called the ‘Pitt vaccine.’ But the newspapers just wouldn’t let go of it. The name Salk was compact, and it was a person—the people could identify that with somebody in a white coat.”

Though Salk stressed his associates’ contributions in an April 12, 1955, Pittsburgh Press article, he failed to do so at a press conference in Ann Arbor, Michigan, that same day. After a field trial with 1.8 million children, the Poliomyelitis Vaccine Evaluation Center at the University of Michigan announced that the vaccine was up to 90 percent effective in preventing paralytic polio. Bennett and the other team members were in the audience, waiting as Salk thanked a laundry list of colleagues and funders. He honored fourteen groups and people before alluding only obliquely to his staff. “There is the group, the role of which seems to be taken so for granted that I may, for the sake of emphasis, seem to exaggerate,” Salk said. “But they gave so much more than they received.” Salk then named eight more people, none of whom were on his staff, before ending with accolades for members of the media.

Bennett rode back to Pittsburgh on a train with James Lewis and “wept most of the way,” according to Breakthrough. The men couldn’t believe that on Salk’s biggest platform yet, their boss hadn’t even mentioned their names. “It was just such an unbelievable thing that my father did not seem to have the awareness that these people, who had put in so much effort and investment, should have their names publicly recognized,” Peter Salk says. “That was just devastating. There’s no question that people had a right to be angry and upset.”

Bennett continued to work with Salk until retiring in September 1956. He underwent surgery for a hip condition that fall and wrote to his sister, Winnie Petty, from the hospital. He shared news of his recovery, lamented that he didn’t think he would get released before Christmas, and complimented Petty on earning her master’s degree. “Do wish I had taken time out somewhere along the line to get a degree myself,” Bennett wrote. Later in the letter, he alluded to his lifelong addiction to alcohol, which the hip surgery had forced him to confront. “One thing this stay in the hospital has done for me is get me on the wagon, and just maybe I will stay on it.”

It’s not clear if Bennett stayed away from the bottle after he returned home. There are no letters or newspaper clippings from that time in the suitcase. But it now seems obvious that he was struggling with depression. On June 9, 1957, Bennett’s wife, Bobbie, was on the phone just before noon when she heard a single gunshot in the house. A story about Bennett’s death ran on page six of the Pittsburgh Press the next day.

She was swimming in grief when she mailed two letters to his parents on August 31. Bobbie seemed to suggest that her husband’s work life had been a contributing factor in his suicide, telling them, “Believe you me the whole scientific world knows the conditions that Byron worked under.” She continued in a second letter postmarked the same day. “There are some who try to convince themselves that Byron died because of alcohol,” she wrote. “I know different, and as of now my mouth is sealed.” In the first letter, she mentioned that she’d had dinner with Youngner and his wife the night before, and that Youngner was still upset with the situation too: “He is so bitter you would think it was his family instead of ours.”

She attached copies of two other letters for Bennett’s parents. One was from Cornelius B. Philip, a researcher at the National Microbiological Institute in Montana. Philip had served in the Medical Corps with Bennett.

“This is a most disheartening letter to write,” he began. “Long ago I knew that his participation in Salk’s polio vaccine studies was a most important contribution,” Philip wrote, “and though his name appeared on some publications, I looked in vain to see him mentioned in news interviews and publicity eventually enjoyed by his chief.”

Philip continued, “This is not for me to guess or discuss as possibly back [sic] of Byron’s decision. It would be very understandable if it was and it is too shocking a result, if so, to contemplate.”

Oshinsky says that when he interviewed Youngner for his book, the former researcher didn’t mention Bennett by name, but gave the author the strong impression that he and the others on the Pitt team had felt deeply snubbed by Salk. They worked for the better half of a decade and created a highly effective vaccine that would eventually eradicate polio in the U.S. The same vaccine is still used today; American children receive four doses before they turn six. But only one name stands out in the history books.

So just how badly was Bennett’s work overlooked? No one is arguing that Salk, as the lead researcher, fundraiser, and face of the vaccine effort, didn’t deserve the lion’s share of the acclaim. “When you talk about Salk’s laboratory, these people were in the shadows, more or less. The question is how much more credit could and should have Salk given them,” Oshinsky says. “I think people will debate that, but the important point is that his lab mates were let down and disappointed.”

Peter Salk points out that the polio vaccine was unique. There’s rarely been another instance when the world was fervently waiting and watching the vaccine process at every step, he notes. “Other than the recent COVID pandemic, I’m not sure if there are other situations in which development of new vaccines has caught the public’s attention in the same way,” Salk says. Nor are the scientists who developed Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines household names. “With the COVID vaccines, the identification has had more to do with the companies working on them than on individual scientists or teams of scientists.”

The year of Bennett’s death, the lab broke up. It’s very unusual for that to happen after such a successful breakthrough, Oshinksy says. In a letter to Byron’s mother and sister, Bobbie detailed where each scientist went. “Dr. Lewis the 3rd one was fired in March and he has left and gone to National drug, and Yougner [sic] has changed to Micro-biology here at Pitt. [S]o there goes the one and only Polio team.”

The last letter in the suitcase was written by Bobbie Bennett and postmarked June 23, 1958. A “Mr. Heyl” had asked her to marry him, she told Byron’s mother, and she’d said yes. “There will never be another Byron and although my heart is broken I try to remember that his job on earth was done—done well, and with a great price.” Two years later, Bobbie took her own life. She and Byron had no children. With no one left to share his story, the pages noting his accomplishments faded to yellow in the suitcase. Even his tombstone is bare of the details that would be included in the first sentence of a New York Times obituary, if he had one. The granite marker is etched only with his name, the dates of his military service, and a title that probably doesn’t resonate much anymore: “Major ORC Sanitary Corps.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Medicine

- North Texas