Q: A dear friend was born in West Texas in the 1920s, and it’s my understanding that it was then customary to name firstborn children after their fathers, regardless of gender. So a girl could be given a name such as Jimmie Gail Smith or Randy Robin Jones. My friend had such a name and even had a friend named Elmo Joy. How did this tradition arise? Is it still followed in West Texas or any other part of the state?

Barbara G. Stephenson, Albuquerque

A: Texas is chock-full of mysterious customs. We wave to strangers while driving in rural areas. We’re vehemently opposed to putting beans in our chili. We clog the shoulders of roadways to take photos of ourselves in fields of bluebonnets while getting bit by angry fire ants. We wear humongous mums at homecoming football games. We’re obsessed with the weather. And, to be honest, we’re kind of obsessed with all of our unique Texas traditions.

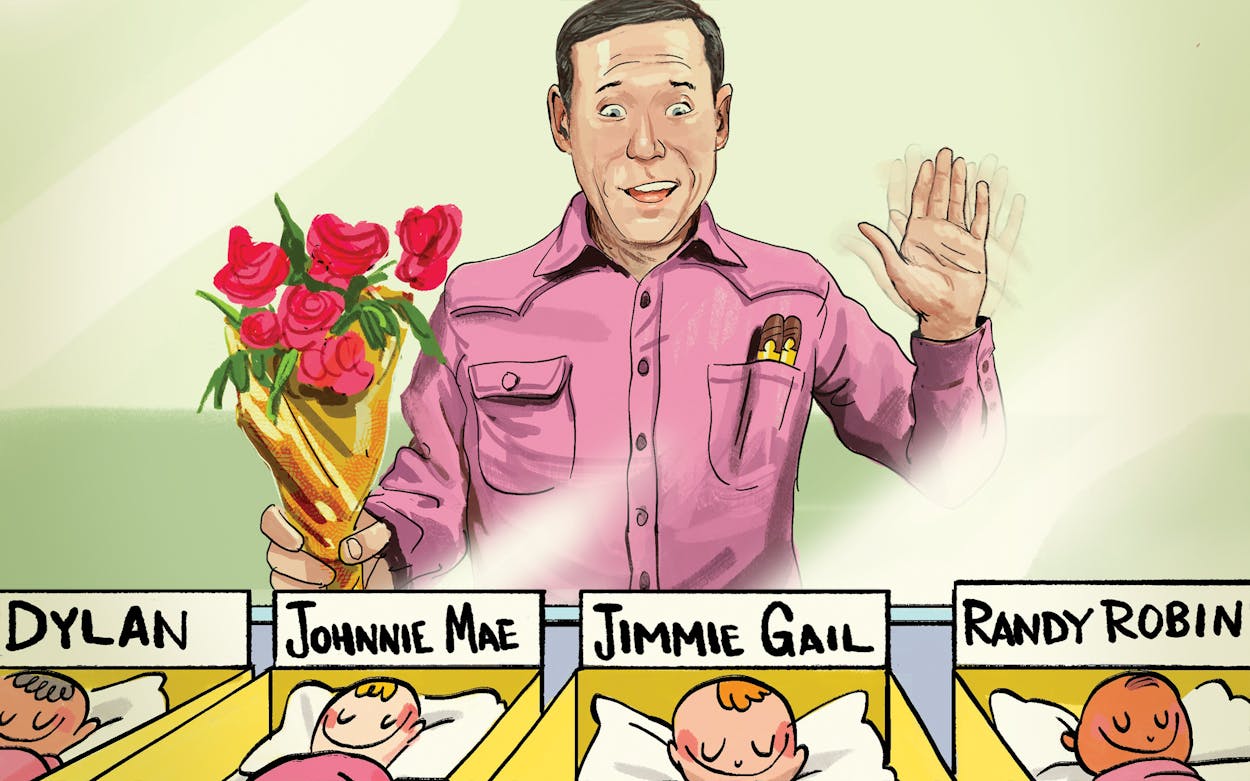

But as far as West Texans giving firstborn babies the first names of their daddies—even if the child happens to be female—well, that’s a custom with which the Texanist is unfamiliar. He is, of course, plenty aware of gals who carry names—either first or middle—traditionally held by fellas. The examples here are, of course, many. Heck, the Texanist grew up in Central Texas right next door to a woman named Johnnie, though she originally hails from Arkansas. And there are plenty of other female Johnnies out there too. There are also lots of girl Jimmies. Who could forget the terrifying Jimmie Sue Jones, the reprobative ne’er-do-well in The Last Picture Show?

Further, a colleague of the Texanist’s grew up in Galveston with three sisters who were, reportedly, Jimmies all: Angela Jimmie, Anastasia Jimmie, and Georgia Jimmie. Another associate, from North Texas, went to school with a girl named Dylan who had sisters named Michael and Tyler. And another colleague of the Texanist’s, noting that in Black communities it’s not unusual for a girl to receive a male name with a feminine suffix attached, cited the many Jamicas, Davidas, and Markeshias she’s known.

What’s more, former model Jerry Hall, who was born in Gonzales, carries a name that’s every bit as manly as those of her exes Mick Jagger and Rupert Murdoch. And Big Spring–born actress Betty Buckley’s mother is Betty Bob Buckley. Then there’s the Midland-born businesswoman and philanthropist Mary Ralph Lowe. Interestingly, the Texanist’s daughter once had a day camp counselor who also was named Mary Ralph something or other.

So, having confirmed that girls are sometimes bestowed with masculine first or middle names, and having noted that this custom is not, in fact, limited to West Texas—or even Texas, generally, as it is somewhat prevalent across the whole American South—the Texanist was left with the task of figuring out if it is customary to give such names specifically to firstborn girls and if it’s the names of their fathers, specifically, with which these women are being honored. Though Mary Ralph Lowe did, indeed, have a father named Ralph, and the Texanist’s old neighbor Johnnie Dickson did receive the name of her father, Jerry Hall and Betty Bob Buckley did not. Getting to the bottom of this puzzler, it became clear, was going to call for some expertise.

Alas, while the Texanist is many things to many people—a devoted father, a loyal husband, a steadfast brother, a meticulous dishwasher, an experienced giver of fine advice, a gentle lover, an accomplished chili cook—there is one thing that he certainly is not, and that is any kind of an onomastician, which is, as everybody knows, an expert in the forms and origins of proper names. As such, the Texanist went in search of such a scholar, ideally one who specializes in Texas naming conventions, though this proved harder than he expected.

After asking around a bit, the Texanist was pointed in the direction of Lars Hinrichs, a professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin. The admirably game Professor Hinrichs, who directs both the Texas English Project and the Texas English Linguistics Lab, informed the Texanist that he was cautiously certain that first and middle female names of the “two-syllable-plus-one-syllable type, like Billie Bob or Johnnie Gail,” can indeed be a way of “using the naming pattern in a patronymic way.” (In layperson’s terms: “naming the child after the father.”) Hinrichs did, though, concede that his research “consisted primarily of talking to people on my street who I know are born Texans, since I couldn’t find a useful academic source on this.”

Hinrichs was also not able to definitively ascertain whether this tradition is reserved for the firstborn child. Nor, he said, was he able to nail down the general status of the custom. Hinrichs did, on the Texanist’s behalf, reach out to some other colleagues, which led the Texanist to Rusty Barrett, a world-renowned sociolinguist and linguistic anthropologist at the University of Kentucky who earned his PhD at UT-Austin. Barrett, in turn, put the Texanist in touch with Brenna Byrd, a fellow U of K linguist who happens to be a native of Austin and also happens to have a great-aunt from the West Texas town of Ozona who was named Jimmie, after her mother’s brother.

Byrd discussed the subject with her mother, who lives in Austin and who has been doing genealogy research in Texas for decades, and the two determined that this phenomenon is not limited to fathers’ names, and it’s not specific to West Texas. “The common thread that my mom and I found in our conversation,” she explained, “was that it was important to name your child after someone you knew. It wasn’t just about a name you liked but about honoring someone or creating an emotional bond between the child and a close adult.” Byrd said she was aware of a common practice among German Texans, in Hallettsville, to name a child—first or middle name—after a godparent. She thought this might be a way to expand a child’s support network. Byrd also said most of the examples that she and her mother came up with were girls who were named not after their fathers but rather after people outside of the immediate family.

All of which, the Texanist thinks, goes a long way toward answering your questions, Ms. Stephenson. Before bidding you farewell, though, he does have one quick question for you, and it doesn’t have anything to do with the ironically patronymic ring of your surname. The middle initial “G” that you included in your valediction—what, the Texanist wonders, does it stand for? Genevieve? Gladys? Grace? Gwendolyn? Or could it, by chance, be short for Gabriel, Gavin, Gary, or George? Inquiring minds want to know.

Have a question for the Texanist? He’s always available here. Be sure to tell him where you’re from.

This article originally appeared in the May 2023 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- The Texanist