Q: These days it is awfully dry out here in the Hill Country. Blanco County is starting to look more and more like Elmer Kelton’s famous novel The Time It Never Rained. What sage advice can the Texanist offer those of us looking up each day, hoping?

William Huston, Johnson City

A: Among the many things for which Texas is well known, its extreme weather ranks near the top. When it gets hot here, it gets really hot. The highest temperature ever recorded in Texas—on August 12, 1936, in Seymour, and on June 28, 1994, in Monahans—was a blistering 120 degrees Fahrenheit, which is very hot indeed. And when it gets cold, it can get really cold. The chilliest temperature ever recorded here—on February 12, 1899, in Tulia, and on February 8, 1933, in Seminole—was a fanny-freezing 23 degrees below zero. According to the Texanist’s careful calculations, which required the use of all twenty of his own digits, along with several belonging to the befuddled stranger on the barstool next to him, that’s a swing of 143 degrees.

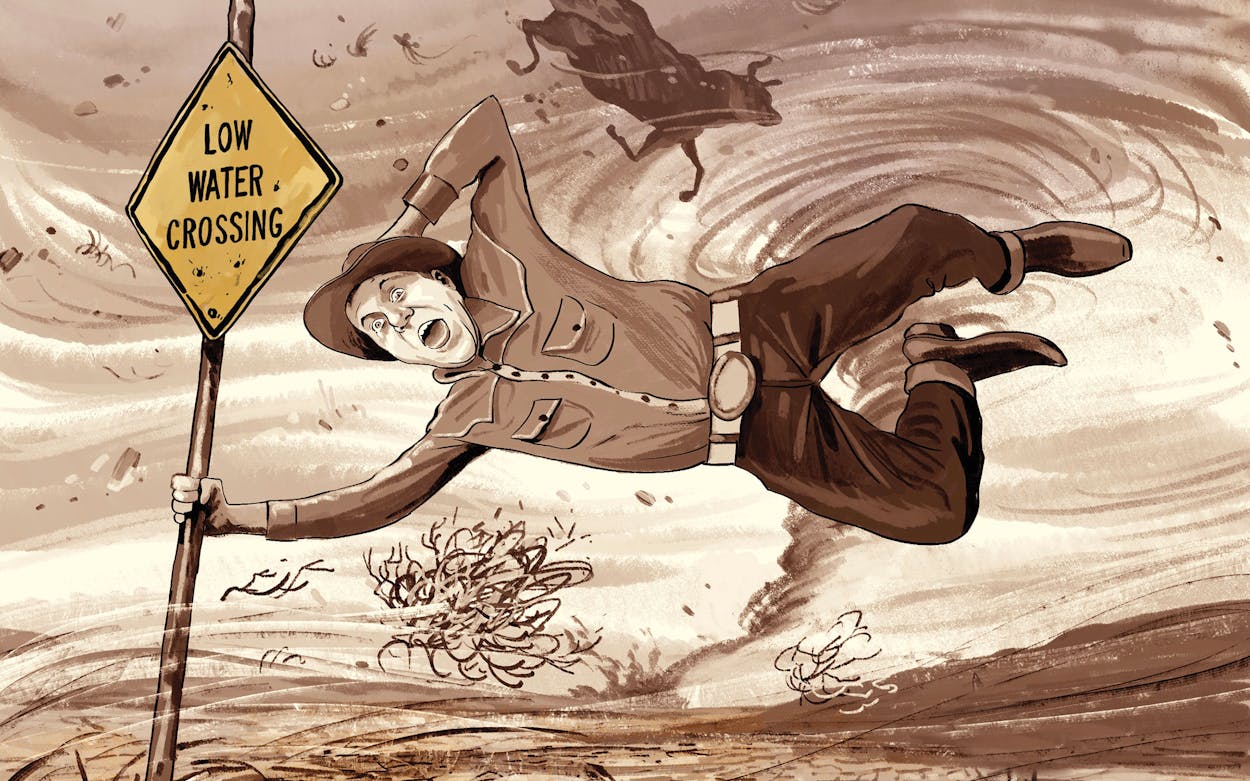

The wind can get pretty crazy too. Texas is, in fact, home to four of the ten windiest cities in the country. They are, in order from windiest to slightly less windiest, Amarillo, Lubbock, Corpus Christi, and Abilene. And in the summer of 1970, Hurricane Celia brought hold-on-to-your-hat gusts of 180 miles per hour to Aransas Pass and Robstown—some of the most powerful winds ever recorded in the country, and the gustiest gusts ever recorded in Texas. And that’s even taking into account the notorious blowhards of the Texas Legislature. Speaking of strong winds, let’s not forget that the southern terminus of Tornado Alley rests in Texas and that the Lone Star State produces more twisters than any other state in the U.S., which happens to produce more than any other country in the world.

And then there’s the topic you have brought up, Mr. Huston: precipitation, and the lack thereof. The nineteenth-century Galveston meteorologist Isaac Cline once said, “Texas is a land of eternal drought, interrupted occasionally by biblical floods,” which is not a wholly inaccurate assessment. When it gets wet here it can get really wet. In July 1979, the town of Alvin was inundated with 43 inches of rainfall in a 24-hour period, at the time the most rain that had ever fallen over any locale in a single day in the entire country. (Though the record was later washed out by a 2018 Hawaiian frog-strangler that measured 49.69 inches.) And who could forget the Memorial Day floods of 1981 and 2015, which devastated Austin and Wimberley, respectively? Or the 60-plus inches of rain that Hurricane Harvey dropped over Southeast Texas in just a few days in 2017—a.k.a. the time it never stopped raining?

Texas is, of course, also no stranger to periods of extended dryness, or, in other words, drought. Though The Time It Never Rained is a work of fiction, it’s set amidst the real-life Texas drought of the fifties, which stretched from 1949 to 1957 and left the state with a 30-to-50-percent deficit in rainfall during a period of higher than normal temperatures. It remains the most severe period of rainlessness in Texas’s documented meteorological history. The memorable drought of 2011, which included the single driest year in state history, was a close second, and there was another exceptional dry spell that peaked back in 1918, not to mention the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s. According to the standard drought index, we are currently suffering through Texas’s fourth-worst drought on record.

For all of these reasons—drought, tornadoes, hurricanes, flash floods, freezing cold, scorching heat, and so forth—keeping an eye on the weather is practically an inborn trait possessed by most every Texan. A significant portion of the Texanist’s day, for instance, is spent wetting his index fingers and holding them up in the breeze, studying cloud movement through his seventeenth-floor office windows, checking the various weather apps on his mobile device, and habitually dialing Temple’s old “time and temperature” phone line, which, oddly, is still in service.

None of this, though, makes the Texanist any sort of expert on the weather, notwithstanding the vaguely annoying know-it-all mien he takes on when the topics of notable gully washers or the dog days of summer come up. So, in search of some professional-grade insight into the current climatological situation, he reached out to John Nielsen-Gammon, a professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at Texas A&M University who has served as the state climatologist for more than two decades and who, readers may recall, lent a hand a few years back when the Texanist tackled a question about hard freezes.

Thanks to the presence of drought, tornadoes, hurricanes, flash floods, freezing cold, and scorching heat, keeping an eye on the weather is practically an inborn trait possessed by most every Texan.

“While at least a tiny fraction of Texas has been in drought since May 2019, the current drought started ramping up in September 2021,” Nielsen-Gammon told the Texanist. As for the county where you happen to reside, Mr. Huston, he says that “at least part of Blanco County has, since April 2022, been in exceptional drought, the worst level of drought according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.” He also explained that between late 2021 and late 2022 Blanco County was about 22 inches below its average annual rainfall of 33 inches, making that twelve-month period its third driest on record, behind the dry periods that occurred in 2011 and 1956.

As noted, that 1956 stretch is the same one that served as the backdrop for The Time It Never Rained. In chapter four, Elmer Kelton accurately sums up the relationship between Texas and drought thusly (spelling the latter in a manner that was and still is customary among some rural Texans): “Other places might have several drouths in a single summer. Texas was more likely to have several summers in a single drouth. Drouth here did not mean a complete absence of rain. It meant extended periods of deficient rainfall, when the effects of one rain wore off long before the next one came so that there was no carryover of benefits, no continuity.”

This is where we find ourselves presently, at a time of year when we ought to be getting a little relief. Alas, Nielsen-Gammon says that the odds favor “a dry and warm winter, as the same patterns in the tropical Pacific that contributed to the current drought are still in place.” The patterns of which he speaks are the La Niña phenomenon, which is caused by cool ocean surface temperatures. Nielsen-Gammon says those conditions are expected to wane in the spring and then everything will depend on what happens during the typically rainy months of May and June. “There’s no cure for drought, except for rain,” he helpfully explained. “If we don’t make up for much of the lack of rain by then, we could be in for a long, hot summer.”

In short, Mr. Huston, the immediate outlook is not very rosy, though the medium-term outlook is not completely devoid of promise. And while the Texanist could call it a day by leaving you with that folksy old bit of sagacity that says if one is not happy with the current weather in Texas one should just wait around for a minute, he will refrain from doing so. Managing meteorological expectations while teetering on the razor’s edge betwixt hopelessness and hopefulness is, after all, a fraught exercise, one not usually alleviated by the deployment of cornpone proverbs. Since humankind still hasn’t managed to find a way to reliably make water fall from the sky on command, we have no choice but to be patient, sometimes exceptionally patient. And maybe a little bit crazy. Especially here in Texas.

Thanks for the letter. May the New Year be prosperous and sprinkled with plentiful—but not too plentiful—precipitation.

Have a question for the Texanist? He’s always available here. Be sure to tell him where you’re from.

This article originally appeared in the January 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Texanist.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- The Texanist

- Weather

- Drought

- Johnson City