This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Descendants of famous Texans look at life the opposite way. They see themselves as ascendant. True, they are anchored to the past by the deeds of their legendary forefathers, but for these six individuals at least, distinguished bloodlines have done more to feed self-esteem than foster puniness. We all have history. Some people just have more than others. They know they’re a little special.

But their legacy is not all glory. With a celebrated family name comes the knowledge that for all your own originality and gumption, you must spend a sizable chunk of your life lugging around the big guy’s bio. “The Maverick name brought me a lot of grief,” says Maury Maverick, Jr. “and yes, it also opened a lot of doors.”

They all agree: Fame is an estate to be tolerated, appreciated, but best not squandered by its heirs. Honor thy antecedents, stay out of trouble—as David W. Crockett advises—and live off the psychic interest. Pass the equity on to the young, lectures Sam Houston IV, and history will lift up even those of us whose names have never been chiseled on a monument.

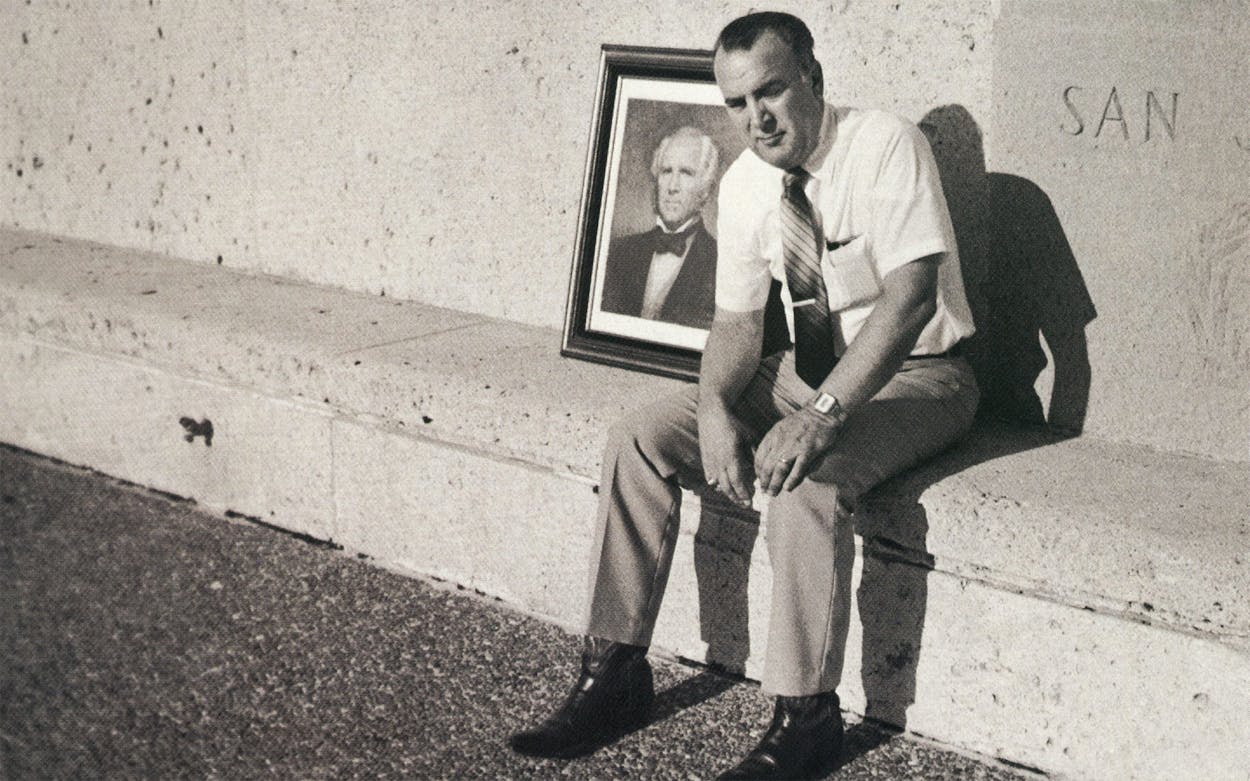

Sam Houston IV

“Remember the Alamo and San Jacinto too” is the battle cry of Sam Houston IV, the great-grandson of Texas’ greatest hero. As a Knight of San Jacinto and the treasurer general of the Sons of the Republic of Texas, the 56-year-old steel salesman travels the state in his spare time to lecture schoolchildren on Texas history. “I do this,” he says, “to teach students that they’re the ones who will one day have to keep our historical sites open and running—not to get them to remember Sam Houston.” Don’t doubt his modesty. He named neither of his sons Sam.

Adela M. Navarro

“Most of the early Texans were scoundrels—Stephen F. Austin included,” says Adela Navarro, standing beside the deathbed of her great-great-grandfather, José Antonio Navarro. “But him they called the white dove. He was always one who preached peace and brotherly love.” Born in San Antonio de Bexar in 1795 and one of two native Texans to sign the Texas Declaration of Independence, Navarro gave his name to Navarro County and Spanish law to the Texas Constitution. “I would like to let everybody know,” says Adela, 83, “that Texas has a better history than they ever have learned.”

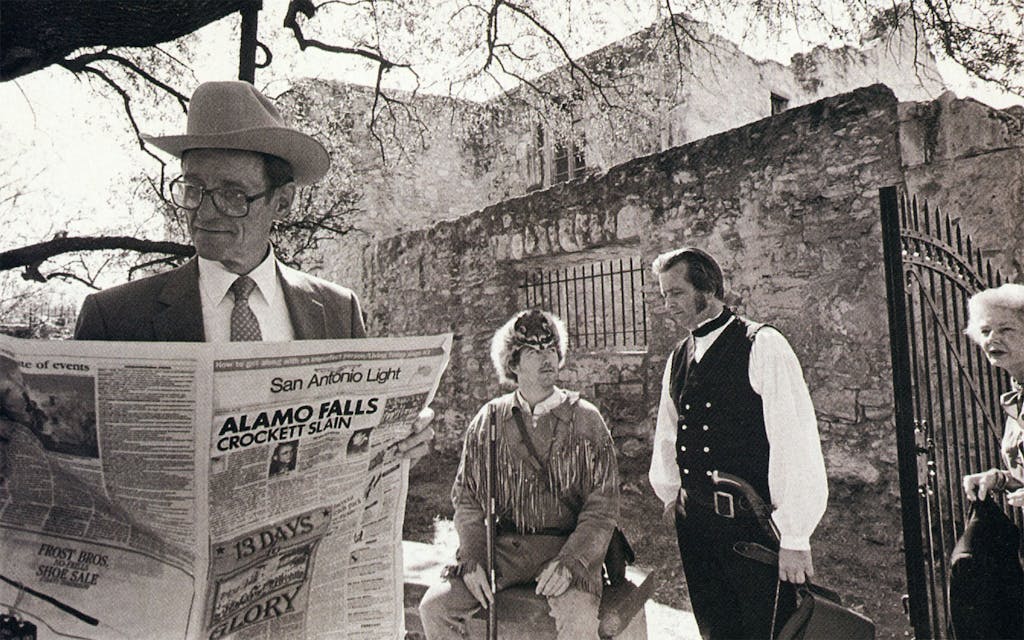

David W. Crockett

Eighteen years after Davy Crockett’s violent death at the Alamo, his Tennessee widow and children settled in Texas with better success. As a boy growing up in Fort Worth, great-great-grandson David W. Crockett welcomed the recognition that accompanied his name and admits it helped him keep his nose clean. Still, the 64-year-old architect says today, “I’d just as soon not go out in such a blaze of glory. I hope to retire and enjoy my grandchildren—something Davy Crockett never got to do.”

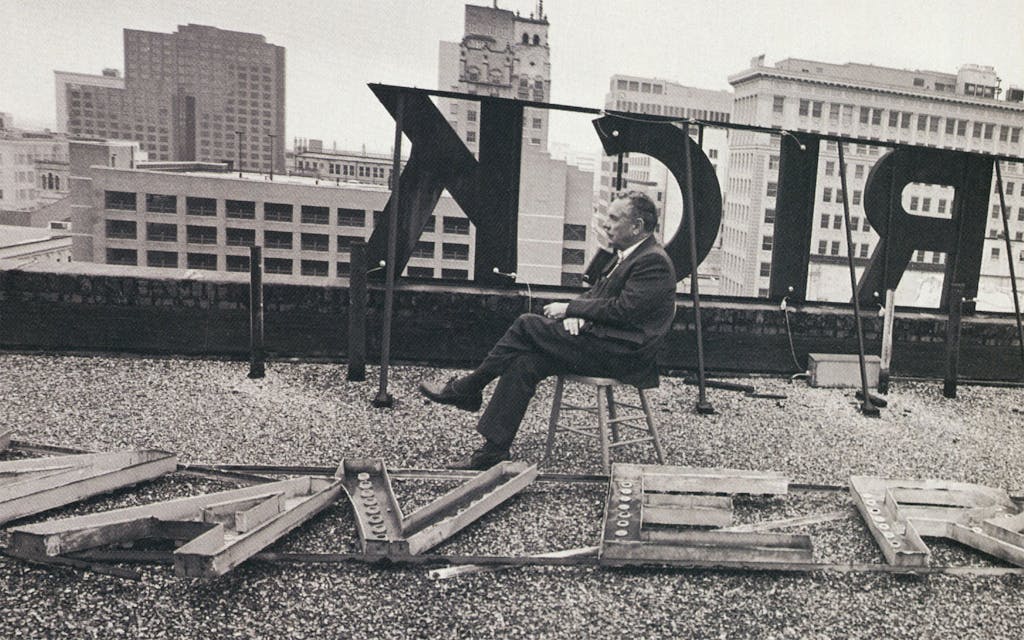

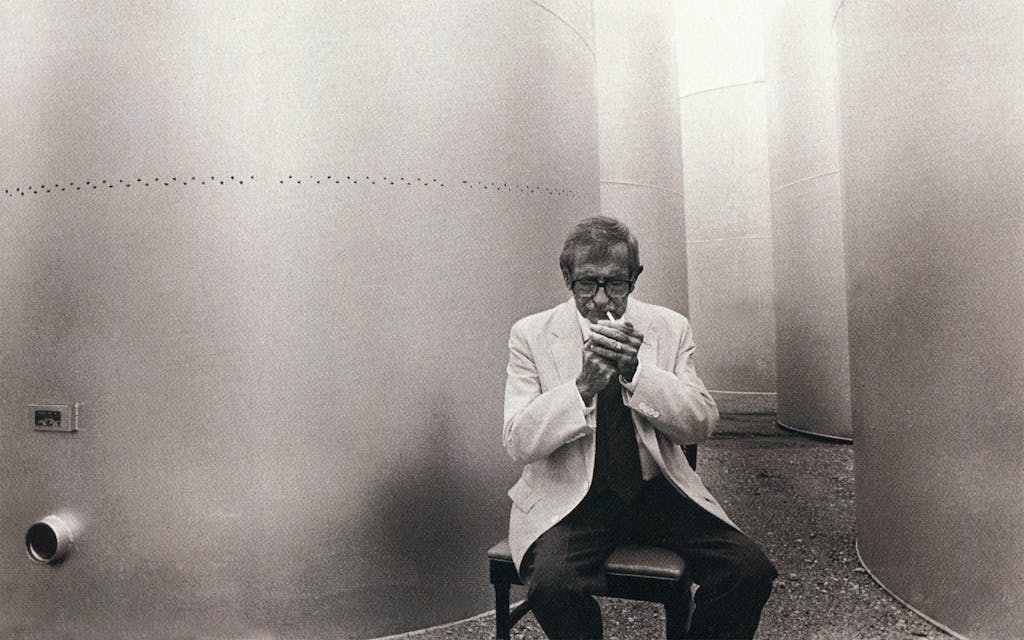

Maury Maverick, Jr.

Mavericks have always been mavericks. A great-grandson of the only Yale man to fight in the Texas Revolution and the son and namesake of one of the New Deal’s more flamboyant congressmen (shown here with FDR), 67-year-old Maury Maverick, Jr., wears his eponym like a set of horns. “When you’ve got a famous name,” the retired lawyer says, “you ought to use it to speak up for the people who can’t speak up for themselves. After all, nobody’s gonna throw you in jail—they know the Mavericks have been crazy for a hundred years.”

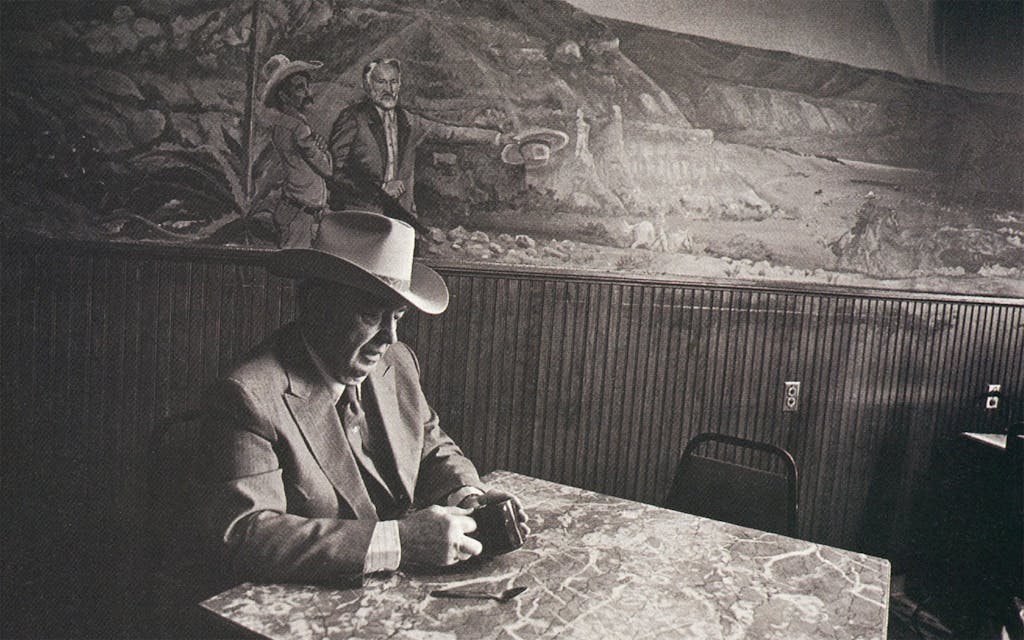

Charlie Goodnight

Charlie Goodnight can’t say for sure what relation he is to the original Charles Goodnight, the Texas cattleman who after the Civil War blazed the Goodnight-Loving Trail, which led from Texas to the Colorado railhead, and founded the great JA Ranch in Palo Duro Canyon. Seems that the Charles of Western legend may have known a lot about breeding livestock, but he never had offspring of his own. Latterday Charlie, 66, guesses he’s a great-nephew, and the proof may well be in the pudding: He runs a roadside cafe in Austin, while his forebear is credited with inventing the original greasy spoon, the chuck wagon.

Verne S. Joiner

Verne Joiner confronts outrageous fortune on a daily basis—partly because of his job with an insurance company and partly because he is the grandson of Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner. In 1930 Dad Joiner (in boater hat) sold the Daisy Bradford No. 3 oil well to H. L. Hunt for $1.3 million. Over the next fifty years, the five-thousand-acre lease in Rusk County earned Hunt an estimated $100 million. Dad Joiner died in 1947, his assets a small amount of real estate and a car. Grandson Verne grew up poor in San Angelo and Dallas. Now 68, he confesses to inheriting few of Dad’s wildcatting ways. “I just play it day to day and always have.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Photo Essay