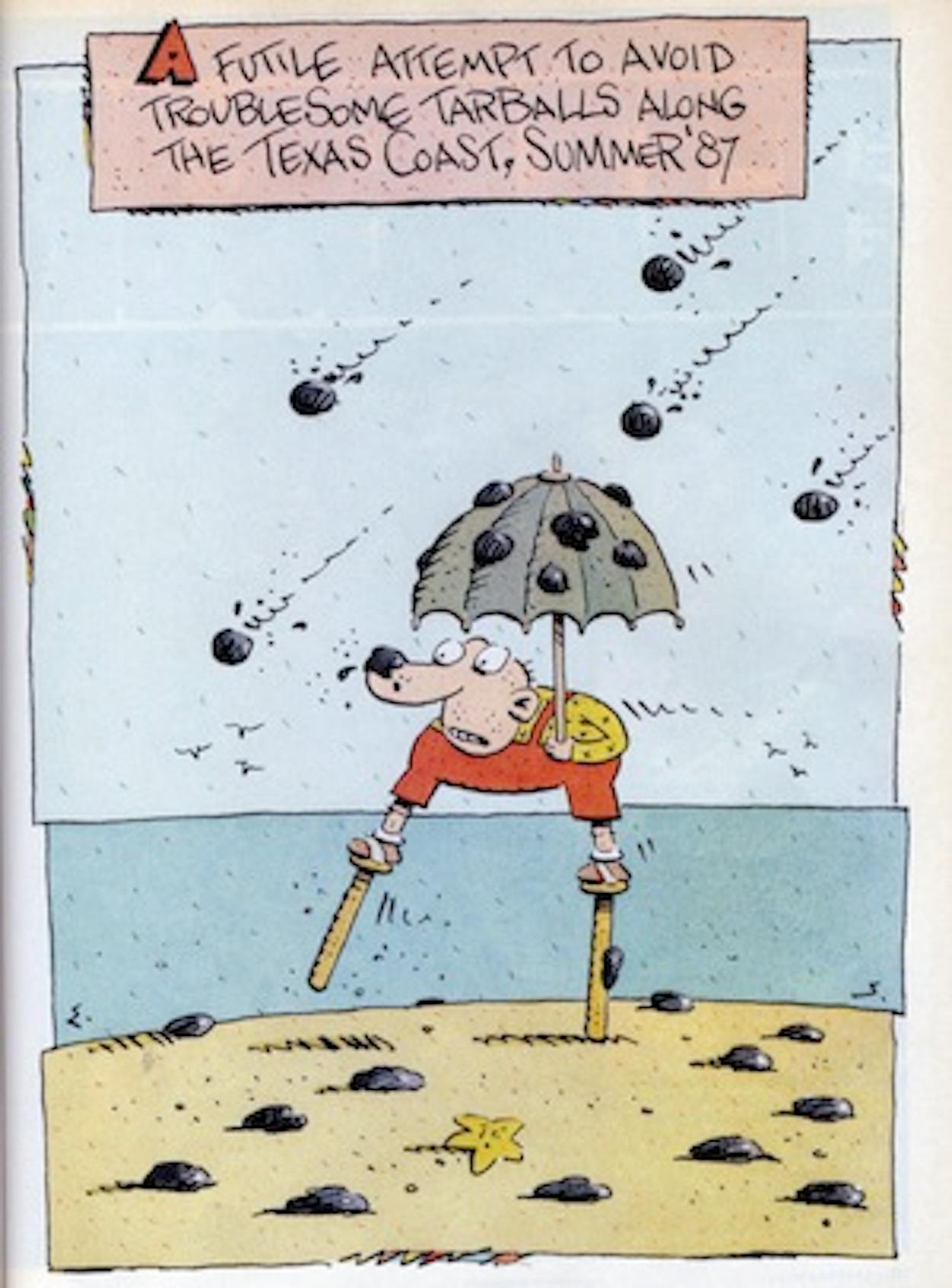

We have reached that time of year when Texans mourn that the Gulf of Mexico is not the Mediterranean and South Padre Island is not Nice. Whatever the virtues of Texas beaches—they are open to the public, and they beat Kansas by a long shot—it is safe to say that they are not likely to be confused with the Côte d’Azur. The water is a murky green and the sand a dismal gray, conditions that are imposed upon us by the Mississippi River, which deposits the silt of Middle America into the western Gulf. Still, we might be able to cope with the aesthetic deprivation were it not for a single dark icon of misery: the tar ball.

Tar balls have been washing up on Texas beaches at least since the days of the Karankawa Indians, who used them to waterproof baskets and pottery. Today the tar ball can be found on the feet of almost anyone who spends an afternoon on a Texas beach. In seaside towns such as Galveston, children are taught early that after a trip to the beach they must not step on the floor before applying kerosene to their feet. Some coastal hotels even provide their guests with complimentary oil-cutting solvents to remove the tar (baby oil, suntan oil, and peanut butter also do the trick).

Perhaps it is only fitting that a state so profoundly dependent on oil should expect oil’s influence to reach right into its playgrounds. Some beachcombers view tar balls as a naturally occurring nuisance, like seaweed or jellyfish. But most tar balls result from acts of man, not acts of God.

Tar balls are just what they sound like: dense accumulations of hydrocarbons that have been mixed and rolled with sand and shells and washed ashore in all shapes and sizes—including a shape and size perfect for pitching at “No Swimming Here to Pier” signs. All tar balls begin as oil originating from one of three sources. First, there are natural leaks along the continental shelf, which runs 40 to 100 miles off the Texas shoreline. Then there are the frequent spills that occur when crude oil is transported from one tanker to another in the Gulf before being brought into port. And then there are the offshore-rig accidents, the most infamous being the Ixtoc I oil spill in 1979, which produced a 100-mile-long, 10-mile-wide blob of slime that began in the Bay of Campeche off the Mexican coast and bellied north across the Gulf to blacken about 170 miles of Texas beaches. The source of the spill was a rig owned by SEDCO, the drilling company founded by Bill Clements, who was then serving his first term as governor, and who called the spill “much ado about nothing.” Much of the tarry fallout from Ixtoc I was caught in sandbars off the coast or buried in the Gulf’s floor, where heavy seas can still dislodge it.

The presence of tar balls on Texas beaches has as much to do with the Gulf’s peculiar hydrography as it does with oil. California, for instance, has more natural oil leaks off its coast than Texas does, because of the more active nature of the Pacific Rim’s floor. It also has its share of spills. But the ocean currents off the California coast are variable and frequently carry away most of the oil before it lands on the beaches. The Gulf, however, is a body of water known among marine biologists as a semi-enclosed sea because of its mittlike shape and its catcherlike hold on whatever enters it. Two currents conspire to deposit as much tar on Texas as possible. One runs southwesternly, beginning around Louisiana and bringing oil from that coast. The other runs northeasternly, beginning off Mexico’s coast and doing likewise with the oil that has seeped out down there. Those currents converge near Port Aransas, off Mustang Island, a ten-mile stretch of sand and shell onto which several tons of tar are estimated to have been deposited—most of it from Ixtoc I.

Nobody has gotten rich from tar balls yet. One aspiring entrepreneur did try to market bottles of the oil that washed up after the Ixtoc spill, but the idea didn’t catch on. Another sold T-shirts that read “Tar Baby. Survivor—Great Spill of ’79.” And during the peak of the spill, one dockside cafe offered oil slick soup—a chicken broth with “seaweed” made of broccoli flowerettes and a “slick” of soy sauce. But those were once-in-a-lifetime items; one doesn’t see tar-ball kitsch for sale in coastal souvenir shacks anymore. In Texas we’ve simply come to endure tar balls, letting them mark our day at the beach as surely as a sunburn.