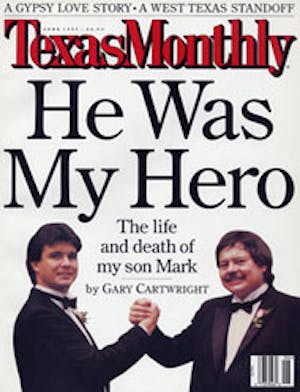

She was a starkly beautiful teenager, with soulful dark eyes and long, thick hair as black as the pelt of a panther. Her name was Janet Evans, and in the late afternoon she would slip out of her parents’ house, a small brick home with signs outside that read “ESP” and “Psychic,” and drive to the Galleria shopping mall in North Dallas, where a stocky, easygoing teenage boy named Frankie Mitchell was waiting for her.

He too had slipped out of his parents’ home, which had an eleven-by fourteen-inch picture of Jesus near the front door and a rectangular “Reader-Advisor” sign in the front yard. Before backing out of the driveway, he would put his red pickup into drive and ease forward a few feet. It was bad luck, he had been taught, to go backward in an automobile before moving forward. And when it came to Janet, Frankie was going to need all the luck he could get.

Together they looked like any other young couple at the mall, strolling past the shops, stopping to eat at Bennigan’s, sometimes slipping into the back of a movie theater. Janet favored sweatshirts from places like Planet Hollywood, Keds, and long denim skirts; Frankie wore NBA team T-shirts, jeans, and black basketball shoes. They never touched, not even to hold hands. But Frankie would lean toward Janet and say that they were destined to be together. After all, they had been born on the same day: August 1, 1979.

“Our parents—they will understand someday,” Frankie would tell Janet.

“Not my parents,” she would reply. When she was with Frankie, she would pour a few drops of her soft drink on the ground, a practice she had been told would pacify the spirits of her dead ancestors. Her mother called them mulé (“ghosts”), and like so many other women in her family, Janet was said to have the gift: She could tell when the mulé were moving. It was clear, said those who knew her, that Janet was on her way to becoming a drabarní, a great fortune-teller who could earn hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

It was the autumn of 1996, and a stranger would never have guessed that Janet and Frankie, such All-American-looking teenagers, were the youngest children of two of the most prominent Gypsy families in Texas. According to one expert on American Gypsy life, the Evanses and Mitchells were the Gypsy equivalent of the Hatfields and McCoys. For decades they had been facing off at Gypsy weddings, parties, and funerals, flailing their arms operatically and hurling obscenities and choice Gypsy phrases at one another (“You will weep as I have wept!”). Members of one family regularly had trooped into police stations to file assault, armed robbery, or kidnapping charges against members of the other. The Evanses alleged that the Mitchells were trying to burn down their fortune-telling parlors; the Mitchells retorted that they couldn’t drive around town without worrying about one of the Evanses trying to run them off the road. Dark rumors circulated that each family’s elderly matriarchs were at work in the back rooms of their little houses, conjuring up “omens” that would be sent the rival family’s way. Most people are amazed to learn that Gypsies still exist. Once regarded as the wild outcasts of society, Gypsies were a visible part of the American landscape in the first half of the century, crisscrossing the country in their ramshackle car-and-trailer caravans, camping outside towns, and speaking to one another in a language known to no one else. They practiced ancient rituals designed to appease the ghosts and spirits they said were hovering over their lives. They wouldn’t comb their hair on Fridays, which they called the Devil’s Day, and made sure to leave the clothes of their dead—neatly folded—in the nicest spot in the forest. They wore coral shells to protect themselves from what they called the Evil Eye, and they refused to go near bodies of water after dark, believing the waters to be inhabited by the spirits of the drowned. American sociologists who studied them were convinced that they would never survive: Gypsies were too backward for a technologically advanced country, too ignorant. They needed to go to school, give up their myths, and learn to work in American businesses.

Today Gypsies seem capable of blending into almost every facet of twentieth-century life. They speak perfect English, live in the suburbs, shop at nice stores, travel on commercial airlines. But at their core, they haven’t changed at all. In the midst of modern life, they exist mostly in an insulated shadow society, one replete with self-imposed codes of conduct, laws regarding marriage and divorce, and strict rules designed to keep their race separated from the gadje (the Gypsy word for “non-Gypsies”); there are even Gypsy courts. What’s more, although few Gypsies make it past the seventh grade and some cannot tell time, they’ve built an astonishingly lucrative underground economy based entirely on the age-old Gypsy tradition of fortune-telling. Once the province of Gypsy women in small carnival tents or shabby storefront parlors, the new Gypsy fortune-telling includes Gypsy-owned psychic hotline telephone services, and the top Gypsy fortune-tellers now advertise in high-profile tabloids like the National Enquirer and the Globe. “It’s not unusual these days for a good fortune-teller from one of the established families to make half a million dollars a year,” says Roy House, a former Houston police sergeant who is still considered one of the nation’s top authorities on Gypsy crime. “Many of the women make $50,000 to $100,000 even if they are not good at it.”

Of the one to two million Gypsies thought to reside in the United States, perhaps 5,000 to 10,000 are in Texas. Until the seventies, the Evanses were considered the most powerful Gypsy clan in Texas, led by their legendary Rolls-Royce-driving “king,” Joe Evans of Fort Worth. But that was before a young Gypsy named Bucky Mitchell, renowned for his unrestrained speeches at Gypsy meetings, challenged Joe’s reign and established his own fiefdom in Dallas. Since then the Evanses have despised the Mitchells—and no one wants revenge more than the Evanses’ leader in Dallas, George Evans, a proud, garrulous character who wears forties-gangster-style hats and struts around Gypsy meetings like a bullfighter entering an arena.

Bucky and George live only twelve miles apart in the Dallas suburbs, but they have not spoken for years. George openly says that Bucky has made a pact with o Beng (“the devil”) to gain more power. Bucky, in turn, believes George is plotting to have him thrown in jail to destroy his reputation as Dallas’ Rom Baró, or “big man”—the Gypsy leader other Gypsies turn to for advice and protection from the gadje.

It just so happens that George’s youngest daughter is Janet. Bucky’s youngest son is Frankie. “You know our fathers will never let us get married,” Janet would tell Frankie during their dates at the mall last year.

“They’ll understand,” Frankie would reply. “I know they will.”

But Janet could feel the mulé. The mulé, she sensed, knew that trouble was looming.

IN EARLY 1995, LONG BEFORE I KNEW ANYTHING about Janet and Frankie, I set out to enter the world of the Mitchells and Evanses in an effort to understand the Gypsy culture. For months, the endeavor seemed hopeless. Whenever I called their homes, I was told by whoever answered that the person I was looking for was out of town. When I’d call back days later, I was told the same thing. Occasionally, I’d drive to Bucky Mitchell’s one-story home in Irving. It was peculiarly humble: The beige walls needed a paint job, and one of the window screens was torn. On the tiny front porch was the picture of Jesus, with a caption underneath that read “Behold, I stand at the door and knock.” The few times I knocked, however, no one answered. When I’d call a few minutes later, a woman with a thick old-world accent would answer the phone and tell me that Bucky was out of town; then she would abruptly hang up. “It’s doubtful they’ll ever tell you anything,” one police officer had warned me. “Gypsies don’t even like people to know they are Gypsies anymore.”

But late that spring, when I heard that the feud was heating up again, I dialed Bucky’s number one more time. The woman put me on hold, and after a few minutes, she told me to be at his house the next day. Apparently, like the good politician he was, Bucky had decided to use the news media to get at his enemies.

At four the following afternoon, I stepped onto the Mitchells’ porch. Before I could knock, the front door opened to reveal Bucky’s wife, Patsy, a plump middle-aged woman in a plain dress. For several seconds she stood silently as her dark eyes studied my face. “When you rang our doorbell those other times, I was in the back room,” she finally said, “but I didn’t have to look to know who you were.”

“You knew who I was?” I asked. I’d been told that Mrs. Mitchell, though now mostly retired, had been a great drabarní in her day. Her customers knew her as Mrs. White. Her business cards and ads had read “Psychic, Crystal and Card Reader … Let Me Help You Obtain Peace of Mind, In Love, Marriage and Business … All Readings are Private and Confidential … Interpret Your Dreams. Call Your Enemies by Name.” Standing in the doorway, I wondered whether this woman really had some sort of psychic ability.

“Okay, perhaps I did not know your name,” she replied, “but I knew you were one of the gadje.” In a dignified manner, her back ramrod straight, she led me into her living room. “Gypsies never knock before walking into another Gypsy’s house. Only the gadje do.”

The living room had the look of a nineteenth-century funeral parlor: There were gold-tipped, rococo-style pieces of furniture, white porcelain lamps, sumptuously draped windows, and artifical flowers on table stands. Against one wall was an elongated couch with dark cushions, and next to it was an oversized wingback chair that resembled a throne. I was mulling over where I should sit when Mrs. Mitchell directed me into the kitchen and pointed to a particular chair at the corner of the kitchen table. Then she disappeared into the back of the house—an area I would never see in all my visits—and returned to the living room with a vacuum cleaner. As I watched, she started vacuuming everywhere I had stepped.

At most Gypsy homes, certain areas are designated for visiting gadje. Often—but not in the case of the Mitchells—the chairs for the gadje are covered in plastic. If drinks must be served, the Gypsies use one set of glasses for the gadje and another set for themselves. For centuries Gypsies have believed that the gadje are mahrime (“unclean”) and that their germs cause many diseases. Spending too much time in the presence of the gadje puts a Gypsy at risk of contamination. If Gypsies move into a home previously occupied by the gadje, they will diligently clean the entire place with bleach, repaint it, and replace the carpets and drapes. There are elderly Gypsies who are so uncomfortable about eating at a gadje-owned restaurant that they bring their own silverware. They will never use public restrooms except to wash their hands—and even then they still can be seen using paper towels to turn on the water faucets.

Suddenly Mrs. Mitchell switched off the vacuum cleaner and said, “Bucky is coming now.” I felt strangely nervous, as if I were about to meet the Gypsy equivalent of a Mafia leader. Several of the Evanses had warned me that Bucky had “soldiers” to protect him, his territory, and his fortune-tellers. A Dallas police detective had told me that Bucky was nicknamed the Fixer because he often came to the police department to help out Gypsies in legal trouble. And that wasn’t all he could do. “This Bucky, he was supposed to have died years ago from cancer—and he is still alive,” marvels George’s brother Bill, who lives in Fort Worth. “Tell me, how can a man cheat death this way unless he made a pact with o Beng?”

“So this is the reporter,” said a cheerful voice. I turned to find a tall but not imposing man in his early fifties (Gypsies never tell how old they are). He was wearing a blue polo shirt, gray slacks, and expensive black leather loafers. “What?” Bucky Mitchell asked with a chuckle. “Did you think I would be in peasant clothes, dancing around a campfire?” “I thought you would look more . . . dangerous,” I said.

He roared with laughter and sat down across the table from me. He seemed as normal as a Rotarian. He told me he was an avid golfer who kept his clubs in the trunk of his Cadillac. He liked watching CNN and old movies. I kept thinking that he was the kind of man I had known all my life.

Then the phone rang. Bucky picked it up, listened in silence for a few seconds, and suddenly launched into one of the most animated conversations I had ever heard. It was carried on entirely in Romany, the Gypsy language. As he bellowed into the phone, he stood up and stalked around the kitchen table like an angry black poodle. In mid-sentence, he slammed down the receiver.

“Sorry, a little Gypsy business,” he said with a shrug.

“A problem with the Evanses?” I asked.

Bucky nodded and then slowly tilted back his head, narrowed his eyes, and gave me the kind of imperious look that theater directors try to coax out of actors hired to play embattled Shakespearean kings. It was a breathtaking transformation. The pleasant fellow I had just met in the polo shirt was suddenly the infamous Rom Baró. “They are trying to destroy me,” he said softly. “But I promise you, my knees will never bow to them. They might try to cut my throat, but I will never bow!”

It was as though I had stepped through a looking glass into a world positively removed from time, filled with characters as comical and uproarious—and as entirely unpredictable—as the Gypsies of lore. When I first saw George Evans, he reminded me of one of those stately old Eastern Europeans who sips coffee in dark cafes. A heavy-featured, formidable man who also is probably in his early fifties, he wears wide-lapelled suits and wide-brimmed hats, and he carries a sturdy black cane decorated with antique gold coins and bracelets.

George is devoted to Gypsy culture: He raised money to create a colorful Gypsy flag—“Until me, there was no flag in the world for Gypsies,” he boasted—and he briefly operated a small local Gypsy museum. And he too is suspicious of the gadje. He never let me come to his house, and he once berated me over the phone when he learned I had visited one of his fortune-telling parlors at a shopping center in Dallas (“Did you ask my permission? No. You are trying to hurt me and my business! You want to hurt the Gypsies!”). It took weeks to negotiate an interview with him; he told me it was part of the Gypsy code that the gadje know nothing about their life. “The more you know, the more you can try to hurt us,” he said. But the knowledge that the Mitchells might get more media coverage than the Evanses finally wore him down. One evening he told me to meet him in the parking lot of a Denny’s next to a highway. When I arrived, he got in my car and ordered me to drive. For ten miles, he had me go down one highway and back up another. Occasionally, he would look behind us to see if we were being followed. Then, after fifteen minutes of aimless cruising, he directed me to Cafe Pacific, the hangout of the society types who live in the ritzy Highland Park neighborhood of Dallas. George chuckled as we got out of the car. Presumably he considered it a great victory that a gadjo (singular for gadje) was going to buy him dinner at such a restaurant.

We were seated at a table next to the proper and soft-spoken Dallas real estate baron Henry S. Miller, Jr., and his wife, Juanita. Within minutes, George’s voice was growing louder, and he began swinging his arms the way all Gypsies swing their arms when they talk. “Bucky Mitchell is mentally crazed for power,” he declared. “He wants to be the Gypsy Al Capone! He knows that if the Evanses bow down to him, all other Gypsies will—and he will think he is the king!”

Out of the corner of my eye, I could see Mr. Miller’s perfectly bald head turn a shade of red. A couple of tables away, two elderly ladies’ eyebrows had risen like window shades. Surely, everyone in the place was wondering how such a person could have infiltrated their world.

ALTHOUGH THE GYPSY RACE, OR THE ROM, as they call themselves, probably originated in northern India, legend has it that they are the cursed descendants of Cain, condemned to wander forever without a homeland. In the thirteenth century they migrated to Europe, traveling in gaudily painted horse and wagon caravans—the first dark-skinned people on the continent. But their vagabond lifestyle terrified most Europeans. The Bishop of Paris proclaimed in 1427 that anyone caught having his or her palm read by a Gypsy woman would be excommunicated. In medieval Romania Gypsies were enslaved and bought and sold for the price of a pig, and in England Queen Elizabeth I ordered them all expelled. In countries like Prussia and Sweden Gypsies were hanged on the grounds that their itinerant lifestyle was illegal. Faced with severe penalties just for being Gypsies, they had no choice but to keep moving.

Like other immigrants, Gypsies came to the U.S. in the nineteenth century to find a better life. They traveled from town to town, where the more industrious men tried to make money by trading horses or repairing copper pots and the women knocked on farmhouse doors to see if housewives wished to have their fortunes told. But most Americans considered Gypsies thieves. No news traveled faster through the small towns of Texas in the early years of the twentieth century than the warning, “The Gypsies are coming!” Storekeepers would lock their doors. Parents, believing the rumors that Gypsies were kidnappers, hid their children in their attics.

But as opposed to immigrant groups who eventually assimilated into America’s cultural mainstream, the Gypsies refused to adapt to the ways of the gadje. Bucky Mitchell and George Evans were part of a generation of American Gypsies raised the traditional way: on the road, traveling in a caravan. Their respective grandparents, who came to America together in the early 1900’s, abandoned their European names and took the common American names of “Mitchell” and “Evans.” (Gypsies always have a Gypsy name that they keep secret from the gadje and a gadje name suited for whatever country they happen to be in.) Both George’s and Bucky’s parents traveled throughout the East and then, in the forties, joined separate traveling carnivals, where the fathers ran midway games and the mothers read palms. When the carnivals shut down for the winter, the Mitchells and the Evanses traveled on their own, often meeting up at the small Mathews Trailer Park at the edge of Fort Worth. The trailer park was mostly known as a haven for the Evans family, whose leader, Joe Evans, was at the time one of the few Gypsies in Texas who could competently read and write English. Unlike the illiterate Gypsies, he did not fear the police. In fact, King Joe, as he was known, became famous among American Gypsies in the fifties when he hired an attorney to file a lawsuit that kept the city’s police from harassing Gypsies and illegally shutting down fortune-telling parlors.

By the late fifties, as many as fifty trailers were pulling into the Mathews Trailer Park for the winter. They were a passionate, raucous group—gathering around fires at night to roast entire lambs, drink cheap wine, and sing ancient Gypsy songs—and they took great delight in deceiving the gadje. (Gypsies felt no compunction about lying to the gadje; when they stole from them, they said it was their way of getting revenge for all the years of persecution.) While some men found legitimate work buying and selling scrap metal or repairing furnaces, others pulled off classic Gypsy scams. They’d bring a Gypsy child into a jewelry store, have him swallow jewelry while they were talking to the clerk, and later remove the jewelry from the child’s feces. They’d tell homeowners, usually elderly ones, that they were repairmen who could seal roofs and repair driveways; after the money changed hands, they’d spray aluminum paint or cheap motor oil over the roof or driveway and then be long gone by the time it washed off.

But the majority of Gypsy money came from the fortune-tellers. To draw customers, the fortune-tellers hid the fact that they were Gypsies; the signs outside their storefront parlors sometimes read “Indian Reader” to suggest that they were of American Indian origin, or they gave themselves religious titles (“Sister” or “Reverend Sister”) to appeal to the devout Christian gadje. The fortune-tellers’ goal was to convince their customers that their lives were plagued by a curse—and that only the fortune-tellers had the power to remove it.

Most customers came to the parlors out of curiosity. Others thought these Gypsy women, with their belief in mulé, did have some ability to foretell the secrets of the future. And every now and then there were clients who were so emotionally unbalanced or desperately unhappy that they would do just about anything for a little peace. The fortune-teller could sense the desperation the moment such a client arrived. Sometimes, all she’d have to do is study the client’s palm, sigh, and say, “I see something bad in your hand. Your money—it is cursed.” Or she would attempt what the Gypsies called the bujo—the big swindle. The fortune-teller would give her client an egg to put on her stomach for a period of time, then crack it open. A master of sleight of hand, she would slip a felt spider in the yolk to show the client that an evil spirit had entered her life. Upon seeing it, the fortune-teller would go into a frenzy, chanting, “There is evil in your body! Your life and your money are cursed!” It was astonishing how many gadje would give their “cursed” money to a fortune-teller to be put in a bag and burned or buried or flushed down a commode—unaware that the fortune-teller had switched the bag and was really disposing of a bag filled with paper.

The dictatorial King Joe lorded over the entire fortune-telling community. He made every Gypsy family in Fort Worth pay him a tax of about $100 a month. In addition to his Rolls-Royce, he owned ten fortune-telling parlors, and his home was filled with crystal chandeliers and Louis XIV—era furnishings. If a Gypsy didn’t follow his orders or tried to avoid paying his tax, King Joe had a simple way of getting rid of him. He would go to the police station and file a complaint alleging the Gypsy had robbed him. When the Gypsy heard the police were after him, he had little choice but to pack up his trailer and leave the state. The prospect of jail terrified a Gypsy: He would be separated from his own people and forced to eat and sleep with the gadje in a gadje jail and even be forced to wear gadje prison clothes. And once he got out, no Gypsies would associate with him for weeks or even months because they considered him mahrime.

Although Bucky’s mother, Florence, was King Joe’s older sister, it was no secret that the Mitchells were considered to have less status than the Evanses. “Since he was a little boy, Bucky felt he had to prove his toughness to the Evanses,” said George Evans, who is a nephew of King Joe’s. After getting through the sixth grade—in that era, quite an accomplishment for a Gypsy—Bucky developed a reputation around Fort Worth as a pool shark, and he didn’t hesitate to speak his mind at regular meetings of the Kris, the Gypsy court composed of King Joe and other community elders.

Still, few people expected Bucky to stage a sort of Gypsy version of the Boston Tea Party. In the early seventies Bucky bought a home in Fort Worth and set up a fortune-telling parlor in the front of the house for his wife, Patsy. When King Joe, who was by then in his seventies, came calling for his tax, Bucky stood in his doorway and shouted, “Your taxing days are over!” He declared that King Joe had no right to tax Gypsies because he was no longer doing anything for them. A furious King Joe promptly filed a criminal complaint alleging that Bucky and his brother Johnny had driven up to his house in a gold Lincoln Continental Mark IV and robbed him of $150. But when the police came to arrest Bucky, he said he was nowhere near Joe’s house on the night in question and was willing to take a lie detector test to prove it. In a stunning turnaround, the police then arrested King Joe for filing a false charge.

The news rocketed through the Gypsy community of Texas and beyond: Bucky Mitchell had humiliated the great Evans clan. He made things worse when he moved his family to Dallas, saying that he was going to build a better fiefdom than King Joe’s. The Evanses said that Bucky just wanted his own territory so that he too could charge a $100 tax.

The feud was on, though a mob war it was not. Because Gypsies don’t believe in murder—they think the ghost of a dead person will return to earth to haunt his killers—a Gypsy feud consists more of grandiose posturing and shouting than it does substantive crime. There were a few fistfights between the Mitchells and the Evanses, some rather lame shoving matches at Gypsy parties, and a car chase in which two heavyset Gypsies rammed each other’s cars throughout the night, shouting curses in Romany out their windows. But for all the antagonism that existed between the Mitchells and the Evanses, no one ever was seriously injured—unless you believe one Jumbo Evans, who claimed that a Mitchell temporarily blinded him after hitting him with a roll of quarters. (Unfortunately for Jumbo, the cops decided that he hadn’t been able to see all that well in the first place.)

As far as the police could tell, the whole Mitchell-Evans feud was little more than a series of attempts by members of one family to file criminal charges, which were almost always false, against members of the other family. After paying fat legal fees to stay out of jail, the second family would then file its own false charges to get back at the first family. Initially, the charges were not even all that interesting: One member of the Evans clan told the police that Bucky Mitchell had pointed a pistol at him at a Gypsy meeting; Bucky, in turn, signed a sworn statement that an Evans had taken a shot at him while he was driving through town in his new pickup. But as more family members from around the state were drawn into the feud, the charges became more creative. Freddie Evans, a young Evans leader who lives in Houston, told the police that he had been kidnapped, tied up, and thrown in a van and that his wife was called and told to leave gold coins and a gold watch and other jewelry in her mailbox as ransom; when the kidnappers got the valuables, they tossed Freddie out of the van. Freddie said that even though his kidnappers wore fake mustaches and eyebrows, he was later able to recognize one of them as a Mitchell.

As the years passed, the feud never lost its fervor. The two families even began fighting with each other at funerals. Ceremonies for the dead, known as pomanos, are sacred in Gypsy culture. An empty table is elaborately set and filled with food so that the dead person’s spirit can eat, and Gypsies clean the clothes of the deceased to make him feel at peace. (If there is no forest nearby, they take the clothes of the dead to a dry cleaner and never pick them up, satisfied in the knowledge that they’re pressed and on hangers and circling endlessly on a mechanical rack.) In 1985 the Gypsies gathered at a Fort Worth funeral home to pay their respects to Rose Evans, a 78-year-old Evans matriarch. Her daughter, also named Rose, arrived with her husband, Steve Mitchell, whom she had married before the feud ignited. Sensing there would be trouble, Steve brought along four armed security guards—but a brawl broke out anyway among the 150 mourners. According to an account in the Dallas Times Herald, “chairs, fists and rocks were thrown as the Mitchells fled in their Silver Spur Rolls-Royce.” During the fight, the casket was knocked over, causing poor Rose Evans to roll onto the floor. The Evanses filed “abuse of corpse” charges against Steve Mitchell, claiming that he had snatched a $3,000 diamond bracelet off Rose’s wrist. At a Fort Worth hearing in which bailiffs escorted both families in and out of the courtroom separately, Steve was ordered to pay a $500 fine.

For the police the feud was a monumental waste of time. But the filing of charges against one another was serious business for the Gypsies. When Gypsy men describe their disputes, they invariably talk of respect. In Gypsy culture, it is vital for a Gypsy man to feel he is being treated with respect by another Gypsy; if he feels slighted in any way, he cannot rest until he inflicts what he calls disrespect on that person. When I once asked Bucky Mitchell why the feud had lasted so long, he sighed dramatically and pulled out a briefcase filled with court documents, newspaper articles, and police reports detailing alleged crimes committed by the Evanses against his family. “Look at these people!” he said. “They have no respect for us!” When I later met with a group of Evanses, I watched them open their own briefcases and pull out similar stacks of papers detailing alleged crimes committed against them by the Mitchells. “You tell me, does this look like any respect for the Evanses?” George snapped. “We will not rest until we get the respect we deserve!”

BY THE NINETIES THE CHILDREN OF Bucky Mitchell and George Evans had grown up and built their own reputations. Of Bucky’s sons, the eldest, Jimmy, was the most reserved; he was happy to let the second-eldest, Joey, act as the family’s heir. The corpulent Joey—obesity is a sign of prosperity in Gypsy culture—was the classic baby boomer Gypsy, nicknamed the Prince by other Gypsies. While Bucky was part of the generation that believed that Gypsies should keep their money hidden, Joey loved to show his success through what the Gypsies called “flash and cash.” He bought a nice new home in Hurst, drove a Rolls-Royce and a Mercedes, wore custom-made suits, and took regular gambling vacations to Las Vegas, where the casinos sent limousines to pick him up at the airport.

Joey, who is 28, was one of the first Gypsies to set up his own psychic hotline. According to the police and other Gypsies, his wife was also a successful fortune-teller who didn’t put a sign in her yard but advertised her hotline in the tabloids. Although the ad didn’t seem like a huge magnet for business—it was one of dozens promising good luck, health, and happiness—the talkative Angie had a steady stream of telephone customers. Joey says now that Angie has canceled her hotline and dropped out of fortune-telling entirely. “The stories about Angie and her money are all lies made up by the Evanses,” he told me. “The Evanses want to make us look like millionaires so that the FBI will start investigating us.”

In fact the Fort Worth office of the FBI did begin an investigation last year into Dallas—Fort Worth—area fortune-tellers. In January an Evans fortune-teller—a niece of George’s—was indicted for fraud after she allegedly took about $10,000 from a 79-year-old Missouri woman who called her hotline. The fortune-teller had supposedly promised the elderly woman that she would “cleanse” her evil money and then return it—but she never did. The police say the new generation of fortune-tellers are con artists. But the Gypsies say their customers believe they are doing nothing wrong. “Angie Mitchell just has an incredible power to make people feel better,” said Bobby Mitchell, a Dallas Gypsy who is unrelated to Bucky but knows Joey and Angie well. “After a couple of conversations with her, they think that she alone has the power to remove a curse. That’s worth a lot of money to people. Hey, you Americans give your money to astrologers and Robert Tilton. Why not the Gypsies?”

Sympathetic words considering that Bobby Mitchell has abandoned much of the Gypsy way of life, one of the few Gypsies in Texas to do so. Unmarried at 35, he dates a glamorous blond non-Gypsy—a huge taboo according to Gypsy law—and owns a large, perfectly legitimate roofing company that does more than $2 million in sales a year. In the eyes of the Gypsies, he has “gone straight,” which is why he is not invited to most of their functions. “Most of the younger Gypsy men won’t admit that they would be lost in this world if they didn’t have their women doing fortune-telling,” Bobby snapped. “Joey is one of the lucky ones making a lot of money. But you have to realize that a lot of guys are not. They are fifty to sixty percent illiterate, and they’re completely computer illiterate. If they don’t change with the times, they’re going to turn into hoodlums who end up in jail.”

Bobby may be proved right, but at the moment it seems like no one is listening. For the Evanses and the Mitchells, fortune-telling is very much the family business, which is why elders of the community start looking early for girls who have the gift. From an early age Janet Evans was drilled by her mother in the art of palm and Tarot card reading. She stood in another room and eavesdropped on fortune-telling sessions. Back in her bedroom, with MTV playing in the background, she would practice saying such lines as, “You are not smiling the way you should,” “There is something in your voice,” “Are you tossing and turning in your bed at night?” “I sense an evil spirit hiding in your money.” When she was in her early teens, her parents signed her up to work at one of the psychic hotlines—a common practice among Gypsies who want to season their girls for adulthood. Earning $12 to $24 an hour, the prepubescent Gypsy girls sit on the phone throughout the day, offering hope to gadje women who are anxious to be loved, to be healthy, or to keep the men in their lives faithful.

Although she calls herself “a nineties girl,” Janet told me that she has never considered anything other than the Gypsy life. She feels no shame about having dropped out of school in the seventh grade—“I don’t think it helps you, if you’re a Gypsy, to be book smart”—and has no doubt that she will spend the rest of her days telling fortunes. “I know some girls who have become Christians and don’t do fortune-telling,” she said, “but I think they will come back. It’s a great life being a Gypsy. We do more by age thirteen than most of you Americans do at thirty.” She gave me a mysterious little smile. As the ends of her lips rose just slightly, I realized why she is said to drive Gypsy boys mad.

Frankie Mitchell first spotted her years earlier at large Gypsy weddings and other gatherings. Although they were usually on opposite sides of the room with their own families, they smiled shyly at each other. Young Frankie seemed to be following in his father’s footsteps. He was a confident, worldly kid who was driving his own car at age thirteen around Dallas, where he made a little money buying used cars and reselling them for a profit. “Why would I want to be a gadjo and have a nine-to-five job?” Frankie once asked me, pointing out that he goes to bed and gets up whenever he wants.

In 1995 Frankie sent word to Janet through a cousin that they ought to meet. It was a risky proposition for him to make even if he hadn’t been a Mitchell. Gypsy rules dictate that Gypsy teenagers have little control over their romantic lives. A Gypsy boy and a Gypsy girl are not allowed to date until their fathers have met and agreed that the two of them should get married. As part of that agreement, the two fathers determine a bride-price—the amount of money, usually around $10,000 to $15,000, paid by the groom’s father to the bride’s father as compensation for his daughter’s leaving his family. If the two men do not agree on a price, the marriage cannot take place. If the teenagers date anyway, a Kris can bring them to trial and label them mahrime, which means they cannot eat or fraternize with other Gypsies for a long period of time. (“For a Gypsy, a fate worse than death,” said Bucky.)

When Bucky was growing up, children rarely got to have any say in who they would marry. Today’s Gypsy kids are given more of a voice in such matters, but parents still get the last word. Indeed, even before their first date was over, Janet and Frankie knew their relationship was doomed, for it would be impossible to get their fathers to sit down and agree to anything. Yet Gypsy teenagers are no different than anyone else when it comes to romance, so they kept slipping away from their homes to meet. They spoke to each other in Romany. On one walk through the mall, Frankie impulsively led Janet into a jewlery store to buy her 24-karat gold earrings.

By early 1996 the Gypsies were abuzz about Frankie and Janet. Joey Mitchell took Frankie aside and said, “You can’t get involved with this girl. Do you know what the Evanses will try to do to us if we take away their daughter?” In fact, when word of the romance reached George Evans and his sons Paul and Robert, they tried to scare Frankie off: According to an affidavit that Janet would later give the police, her father forced her to file criminal complaints claiming that Frankie had been stalking her, pointing a gun at her, harassing her by calling her twenty times a day, and even slapping her in the parking lot of a movie theater. To keep the feud from getting out of control, Frankie and Janet lied to their parents and said that they would no longer see each other. But they knew time was running out: Patsy Mitchell was urging Bucky to find another girl for Frankie, and George Evans was looking for a Gypsy boy for Janet.

In the first week of November, Frankie and Janet sneaked out of their houses before their parents had awakened and met at a movie theater parking lot; they then drove to Houston. In her affidavit to the police, Janet called her family from Houston and told them she and Frankie had eloped. (A practical Gypsy girl, she also told them where she had left her car, a white Mustang, so her family could go get it for safekeeping.) In Gypsy culture, an elopement is not the same thing as marriage. An elopement requires the boy’s parents to pay a $2,500 fine to the girl’s parents, and the parents have ten days to agree on a bride-price. If they don’t, the girl must be returned to her home.

The Evanses, of course, weren’t going to discuss anything with the Mitchells. George’s son Paul went so far as to file a police report claiming that the elopement was actually a kidnapping. He charged that Frankie and his mother had burst into his Dallas home wielding pistols, raced into the bedroom where Janet was supposedly staying for the night, and dragged her away as she kicked and screamed. Yet when a Dallas police detective questioned Janet, she said she had not been kidnapped—she had not even been staying at her brother’s house. Completely exasperated, the detective filed a misdemeanor charge against Paul Evans for giving a false report.

But the Evanses weren’t giving up. Because George wouldn’t agree to a bride-price, Janet had to be returned to him. Janet later told me that she went home because she thought her father would eventually come around and let her marry Frankie, but the moment she arrived back at her house, in mid-November, her parents were waiting for her with the car running. They put her in the back seat and started driving north: George supposedly had found a family in the Midwest with a son who would be willing to marry her. According to the police, when George stopped in Oklahoma to get gas, Janet dashed out of the car, told the attendant she was being kidnapped, and begged for protection. The police arrived and decided to take Janet to a juvenile facility until the matter was resolved.

Now Janet was faced with a bigger problem. At the detention center she was put in a room with gadje girls and told she would have to sleep in one of the gadje beds. Janet became nearly hysterical: She couldn’t stay with gadje. As openmouthed gadje girls looked on in amazement, Janet busted a window, crawled through it, and fled into the night. She called Frankie collect, and he came to get her. The lovers were reunited.

At that point, according to Bucky, the leaders of the Kris ordered the two fathers to agree to the marriage. Nothing, one Gypsy elder said, was going to keep Janet and Frankie apart: They would simply elope again and start the whole process over.

Bucky said that a bride-price was agreed upon through the Kris and that he paid George. George, however, told me he received no payment; thus, there was no marriage. Regardless, Bucky rented a hotel ballroom in downtown Dallas for New Year’s Eve and invited 150 guests to celebrate the traditional Gypsy wedding of Frankie and Janet. He also hired private security guards to make sure the Evanses were kept out. Throughout the day, the hotel’s management received anonymous phone calls from men saying that the hotel would be bombed if the Mitchell party was allowed to take place. But the “wedding” went off without a hitch. (Because Gypsies refuse to take out civil marriage licenses, their weddings are not considered official marriages by the State of Texas.)

Janet wore a new dress of white lace; Frankie wore a tuxedo with a red sash, the Gypsy sign for health and happiness. As the ceremony began, a red veil was put on a long red stick, decorated with ribbons, and carried around the room by a group of unmarried girls. As everyone gathered in a circle around Janet, the stick was lowered, and the veil was removed and placed on her head. Then members of the Mitchell family escorted Janet across the ballroom, a sign that she had moved from one family to another.

Afterward Bucky walked around the ballroom carrying a large loaf of French bread, known as the dowry loaf. As their wedding presents to Frankie and Janet, Gypsy men pulled out their billfolds and stuffed money into the dowry loaf. Then everyone drank wine and hard liquor. A deejay played American pop music, and when it came time for Frank Sinatra’s version of “New York, New York,” Bucky got out on the floor and performed an old-fashioned Gypsy dance, putting his arms in the air, snapping his fingers, twisting his shoulders back and forth. Frankie was embarrassed, strangely enough: Of all the things about Gypsy life that might have struck him as bizarre, the only thing that seemed to bother him was his father’s dancing.

IN MARCH I MET GEORGE AND A GROUP of other Evanses at a Pappadeaux’s restaurant. They had brought their briefcases filled with papers, and their eyes were blazing. George told me that he knew Janet did not love Frankie and that she was being beaten and drugged at the Mitchell home. “She’s like Patty Hearst!” he said. “She has been brainwashed, and now she’ll do anything the Mitchells say. The Mitchells made her turn against the family. . . . My daughter is in the middle of everything, she is a confused child, and I can’t do anything about it.”

“If you believe so many horrible things are happening to Janet,” I asked, “why don’t you barge into the Mitchell house and save her?”

George impatiently shook his head, as if I still didn’t understand anything about the feud. He told me the Mitchells were just waiting for him to come to their house so they could have him arrested for trespassing. “If I call over there, they will try to have me arrested for harassment. I asked the Irving police to go with me to see my own daughter, and they said, ‘No, handle your problem in your own Gypsy courts.’”

It was clear the feud would never end. Since Janet and Frankie’s elopement, the Evanses had been trying to get gadje politicians to support them in their fight. A group of Evanses had traveled to Austin to warn state representatives about Bucky Mitchell. An Evans delegation appeared before the city councils of Fort Worth and Irving, where speakers read a statement describing the Mitchells as a “Gypsy gang” involved in “organized crime.” The council members, none of whom had any idea who the Evanses and the Mitchells were, tried to look concerned. “I promise you, things are about to happen—big things—that will bring Bucky Mitchell down,” George Evans told me. “A man who makes a pact with the devil cannot live a happy life.”

A few days later, when I passed on George’s comments to Bucky, he laughed, but then he grew solemn and knocked rapidly on the table with his fist while making a kissing sound with his mouth. (If the devil is mentioned in their presence, Gypsies often make particular noises to keep him away.) “I feel pity for that family,” he said. “They still wish they were the kings. Their day is over.”

As Bucky and I talked, Janet and Frankie walked into the kitchen to eat Whataburger hamburgers. (It is traditional in Gypsy culture for the youngest son to stay with his parents to take care of them as they age.) Janet rolled her eyes at the mention of the feud: To her, it was a silly thing the men did to pass the time while the women made money telling fortunes. Frankie, of course, was already in the thick of it. He had just learned that one of Janet’s brothers had filed a complaint with the police saying that Frankie had thrown a hairbrush at him at a nightclub. “These Evanses are crazier than ever,” Frankie said. He glanced at Janet. “Some of them are.”

When I brought up the subject of their romance, Frankie and Janet got flustered and excused themselves from the room. “Normal teenagers,” Bucky said with a laugh and a wave of his hand. And that, I thought, was that: the end of the most passionate chapter in the history of the Mitchell-Evans feud.

But as I should have learned long before, nothing in Gypsy life, and especially in this Gypsy feud, is ever predictable. In the first week of May George called me at home to announce triumphantly, “She’s back home! She is with us! What did I tell you? These Mitchells could not keep her kidnapped forever!”

I quickly called Bucky, who sighed and said that Frankie and Janet had gotten in a spat a few days earlier and that Janet had stormed out of the house and driven back to her parents. “These fights happen all the time with young headstrong Gypsy couples. She’ll be back in a few days.” In fact, added Joey, Frankie and Janet were already talking again on the phone. “Janet is telling Frankie she’ll come back if he’ll pay her more attention. You have to remember, they’ve only been together three months. They’re just kids. This kind of Gypsy fighting is no big deal.”

Still, the Gypsy community was buzzing with rumors about what would happen next. Some Gypsies said George would again try to take her away and marry her off to another Gypsy boy. Others said it was too late: Janet would not be valuable on the Gypsy marriage market because she had been attached for so long to Frankie. Although George wouldn’t let me interview Janet, he declared that anything she had told me in earlier interviews about her alleged marriage was inaccurate because she had been “under the drugged influence of the Mitchells.” In a rare concession, however, George did admit that he wasn’t sure how long Janet would stay at his home. “I don’t know. She might go back over there. Her mind has been so corrupted by them.”

Perhaps, I thought, she had returned for a while to her old home simply because she just missed her parents, especially her mother, who had taught her everything about the old Gypsy ways. I remembered how Janet had once told me that after she had come back from Houston with Frankie, her mother wouldn’t speak to her. “She thinks I’ve gone crazy,” Janet had said, and she blinked a few times to keep her composure—a beautiful girl trapped in a feud that she would never understand. “They’re like pawns, she and Frankie,” said Bobby Mitchell, the Gypsy who has walked away from Gypsy life. “It’s tough enough being a young Gypsy couple in this world, and when you’re being pulled by your families in all directions, it’s hard to stay together.”

In my two years with the Gypsies I struggled to understand their ancient passions and bewilderingly primitive taboos. There were many times when I thought they were not all that different from the rest of us. After several visits to the Mitchells, they began to let me sit in different chairs around the house, and on one of my last visits, the dignified Patsy had even offered me a pinch of johai, a greenish bread that the Gypsies eat on special occasions to ward off evil spirits. “May you have good luck in your life,” she said in her old-world accent. “Good luck and many children.”

But as I got ready to leave, I had no illusion that I would ever really know their world. Bucky had gotten on the phone and was arguing to someone in Romany—no doubt another fight over the Evanses—and Patsy had disappeared into the back of the house. By the time I closed the Mitchell’s front door behind me, I could hear the whir of Patsy’s vacuum cleaner going over the very spots where I had stepped.

- More About:

- Dallas