This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Brisk, businesslike, Anne Bass enters wearing a tight black leather skirt, spike-heeled blue shoes and a blue angora sweater with large shoulder pads. Her straight blond hair is held back by two gold barrettes shaped like bows; a wide gold necklace, or to be more exact, a gold collar molded like coils of rope, emphasizes her correct posture. “I brought you some things I thought you might use,” she says, leading the way to a table that looks out over a meadowlike swath of lawn. “There’s this.” She opens a folder and hands me a neatly typed résumé.

Listed below are her directorship at Bass Brothers Enterprises and memberships, divided between those she describes as cultural (such as the International Council of New York’s Museum of Modern Art) and social (such as Fort Worth’s Jewel Charity Ball committee).

“And then there’s this,” she says, handing me two single-spaced typewritten pages. “Another journalist submitted some questions about the Fort Worth Ballet. I don’t have the questions anymore, but these are the answers.” She gives me a moment to scan the pages, then leans back in her chair, indicating that I might commence. “So, what is it you want to ask?”

Anne Hendricks Bass

Born: October 19, 1941, Indianapolis, Indiana

Married: Sid Richardson Bass, of Fort Worth, Texas, June 26, 1965

Graduated: Tudor Hall School, Indianapolis, 1959

B.A. Degree: Vassar College, 1963

As Anne Bass’s résumé makes clear, she is married to Sid Bass, one of the richest men in America, and with the Bass fortune behind her, she has become a powerful patron of the arts in Fort Worth and New York. She is a well-known socialite who is also relentlessly private. She has agreed to talk to me with the stipulation that I not ask “anything personal,” a reference to her husband’s much-publicized decampment with Iranian-born Mercedes Kellogg, the wife of Francis Kellogg, a 69-year-old businessman. I know that Anne Bass has not filed for divorce and that the rumors of a $500 million settlement are premature. But even if she wouldn’t talk about her marriage, I wanted to understand why it is a subject of gleeful discussion in Fort Worth and New York. A New York magazine article about the affair said: “In a departure from the typical scenario in which everyone feels sorriest for the abandoned wife, little sympathy seems to be going to Sid’s.” Anne and Sid were seen together recently at The Nutcracker in Fort Worth (their daughters danced), but this was not necessarily a sign of reconciliation. Suzy Knickerbocker reported in her column that Sid and Mercedes had taken a house for Christmas in the Dominican Republic.

I might not have been able to ask about the domestic drama, but I still wanted to know why people in Fort Worth’s art world were so reluctant to discuss Anne Bass at all with me. And I wanted a look into the realm in which she wields so much influence—that secretive world where art and money converge.

Beginning at the obvious place, I ask how she had become interested in ballet.

“That’s answer number one,” she says, pointing to the sheets of paper. “You can read what it says.”

“You do believe in the printed word,” I say after glancing at the page.

“Yes, that way there are no mistakes,” she answers and smiles primly.

“Perhaps we should proceed more generally,” I say after reading how she had taken ballet lessons as a girl. “Talk about your motivation, your background . . .”

“Well, in my family, the way we were raised, one contributed to life. When I married Sid, I found myself in an enviable position—that I could participate. I wasn’t going to spend my time playing tennis and bridge. I was going to do something else.” She tells me about her early volunteer work in the Junior League, then as she talks about her family in Indianapolis, she warms up, revealing a sense of irony about herself. She has deep blue eyes, and when she smiles her face resembles the mask of comedy. The corners of her eyes turn down as emphatically as the corners of her mouth turn up in an expression that’s as poignant as it is mirthful.

Anne Bass’s father was a prominent surgeon and urologist, and her mother a champion golfer. Anne’s mother had gone to Vassar, and Anne and her siblings were expected to excel. “My grandmother and my mother both loved dance. My mother wanted to be a dancer, but my grandfather wouldn’t allow it. I took ballet when I was little and in high school. I went to public schools until my last two years, but I never could sort out my parents’ academic expectations and the social demands at school, where boys and being a cheerleader were everything. I was much happier at Tudor Hall, a private girls’ school in Indianapolis. We didn’t have to worry about boys and could just get down to business. Everyone was trying to get into good schools, and we had some wonderful teachers. The woman who taught English had gone to Vassar, and the history teacher’s room was completely lined with historical novels. If you read twenty each six weeks, you got extra points. I did it every six weeks. I also got points for posture.”

As she recalls her childhood, it becomes clear that from her earliest years she has been compelled by a need for control and a desire for perfection. At one point, she shows me snapshots of her family; one is a wintry photograph of herself with her younger sisters and brother on the terrace of her grandparents’ penthouse in Indianapolis. What I am seeing is the world that F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote about, of people who grew up in cities in the Midwest, who sent their children East to the best schools. The sort of people who, for a time, not only defined the best that middle-class America had to offer but also believed in that naive concept of “best.” When she shows me a snapshot of her husband and his roommates in their caps and gowns at Yale I remark on how nice they look. She says with a note of regret, “Yes, they were the best.”

Anne’s grandfather R. D. Brown was a well-known builder in Indianapolis and a philanthropist. He went into the oil business during the forties in Fort Worth, where he knew Sid Bass’s great-uncle Sid Richardson. Richardson was a wildcatter, famed for using a phone booth at a Fort Worth lunch counter as an office until he discovered the Keystone Field in West Texas, where he drilled 385 wells, hitting only 17 dry holes. Two of the Browns’ children ended up raising their families in Fort Worth, and as a child, Anne would take a train with her family to visit her Texas cousins, aunts, and uncles. “I met Sid at a birthday party here in Fort Worth when I was nine years old,” says Anne. “According to his mother, he went home and said he was going to marry me. That’s what his mother always says, but I think she sort of made it up when we decided to get married.”

Anne and Sid Bass started dating when she was a senior at Vassar and he was a sophomore at Yale. She went on to New York City, where she took a job as an executive trainee at Bonwit Teller. The week after Sid graduated, they were married in a Presbyterian ceremony in Indianapolis, had a reception at the Woodstock Country Club, and after a honeymoon in Europe, lived in Dallas for a year while Sid picked up some practical experience before entering business school at Stanford. In Dallas, Sid rode the bus to work and, thinking he might pursue his interest in art, he painted in the spare bedroom. After two years in Palo Alto, California, and a summer in New York, they moved home to Fort Worth.

“And was there any problem making the transition to this?” I ask, gesturing toward the gardens outside and the magnificent house around us.

“I don’t understand,” she says.

“Was it ever difficult, having so much money?”

“No, but I remember when Sid came to Indianapolis to ask my father’s permission to marry me. I went with my father to drive Sid to the airport, and on the way home he told me how much he liked Sid but asked if I was sure I wanted to marry him. He said I should think about it because great wealth could breed a lot of unhappiness.”

“And?”

“I thought about it and decided I could handle it.”

To appreciate the impact that Anne and Sid eventually had on Fort Worth, you have to understand a little about the city. Originally a cow town, Fort Worth became headquarters for big ranching families in West Texas—the Fortsons, Carters, Walshes and Moncriefs—who in turn became big oil families. To get a sense of this past, all you need to do is drive through old Westover, which is far and away the city’s most exclusive neighborhood. The Spanish castles, French chateaux, and English manor houses on Crestline and Westover stand on a bluff and look out over the Trinity River bottom, where you can imagine cattle drives heading north. It is also easy to envision the Fort Worth millionaires heading to Europe in the thirties and forties to pick out the kind of houses they wanted and to buy furniture and paintings. Socially, Fort Worth is a small, closed town, a community of two hundred or so rich families who are most comfortable in their own company. It was and still is the sort of town where social life takes place at the country clubs, where people reach for the social directory when they want a telephone number. According to one longtime resident, people from Fort Worth as recently as fifteen years ago didn’t go to New York alone. They might go in a small group, but alone they didn’t know where to eat, what to do, or anyone to see.

Anne and Sid Bass returned to Fort Worth in 1968 with their own strongly defined interests and tastes. Sid was from what was generally considered the richest and most respected family in town. His father, Perry Bass, had grown up in Wichita Falls, where his father was a doctor. Perry went to the Hill School in Pennsylvania, then to Yale. When he graduated, he came to Fort Worth, where he went to work for his uncle Sid Richardson and married Nancy Lee Muse.

A lifelong bachelor, Sid Richardson left an estate that was assessed at $105 million when he died in 1959. Perry Bass was his uncle’s sole partner, and each of Perry’s four sons inherited $2.8 million, with the bulk of the estate going into the Sid Richardson Foundation. In 1960 Perry Bass had combined the money his sons inherited to form Bass Brothers Enterprises (which the brothers broke up late last year), ultimately contributing his own share of the Richardson companies. When Sid, the oldest son, returned to Fort Worth, Perry Bass retired and handed him control of Bass Brothers, which had an estimated worth of $50 million.

Anne and Sid bought a rambling, ranch-style house, where they had a view of the Trinity River bottom. From the first, people watching them had the sense that the Basses were designing the perfect life for themselves. They had two daughters and conducted themselves as model parents. They made a small group of friends with whom they would raise their children. They knew what they wanted their future to be, and they knew how to bring it about.

“They would have captured people’s attention if for no other reason than by the precision of their tastes,” said Jane Brown, a friend who is now the executive director of the Fort Worth Ballet. “It seems like they were always the first people in town to have a silver car or whatever, and I’m sure that after a visit to Anne and Sid’s, a lot of people went home and put their gewgaws in the closet. When their girls were little, Anne found a shop on Madison Avenue that had the best Mary Janes, so everyone in Fort Worth would trace their children’s feet on a piece of paper and send off for their shoes there. ‘Tastemaker’ is an old-fashioned word, but I suppose that was what they were.”

The fact was that Anne and Sid Bass weren’t trying to capture anyone’s attention —the family was not only the most prominent in Fort Worth, but it was also the most reclusive. The role that attracted Anne and Sid was that of patron, and 1968 was a fortuitous time in Fort Worth for the budding philanthropist. Amon Carter, Sid Richardson, and Kay Kimbell had made collecting a sensible avocation as well as a source of community pride. The Amon Carter Museum had opened in 1961 and was a great success. Richard Brown had come from the Los Angeles County Museum in 1966 as founding director of the Kimbell Museum of Art, and in 1968 Henry Hopkins followed to turn the Fort Worth Art Museum into a professional institution.

Anne was a hardworking member of the Junior League, but according to her contemporaries, she was better at running things than at taking orders. The league asked her to be community arts and education chairwoman, and in 1969 she and her husband were invited to join the board of the Fort Worth Art Museum. Financially, they brought a direct connection to the Sid Richardson Foundation. When Anne and Sid joined the board, Perry and Nancy Lee—as the foundation was usually referred to in Fort Worth—were giving the museum a $25,000 annual stipend. Three years later the Sid Richardson Foundation paid for a $1 million expansion at the museum. In the past the foundation had put most of its resources into education and health, but more and more it began to reflect Sid and Anne’s interests, spending increasing amounts in the arts.

Anne Bass’s development as a patron did not take place entirely within the realm of public institutions. In 1970 she and her husband commissioned the distinguished New York architect Paul Rudolph to design a house for the thickly wooded eight-acre tract of land that they had purchased in new Westover. They spent a year planning, then two years building. The project took so long people in Fort Worth became embarrassed to ask how it was going. But what the Basses ended up with is one of the most beautiful houses in Texas: serene and white, it rises out of the treetops in a series of rectangular boxes, one stacked on top of the other, ends jutting out dramatically like cantilevered bridges.

Having completed the house, Anne started on the grounds. To prepare herself, she had already visited many of the great gardens of Europe. She had read extensively in horticulture, botany, and landscape architecture, assembling her own gardening library. After having Bob Zion, an East Coast landscape architect, lay out the grounds, she chose Russell Page to plan the gardens. Until his recent death, Page was the leading British landscape architect. They moved hillsides, created meadows, sculpted views, built lily ponds and greenhouses, and planted rose gardens. By the time they finished, Anne and Sid had spent several million on the gardens.

Money, however, was not a problem. Following the 1973 Saudi embargo, oil began its steady climb and Sid Bass began assembling his investment team. By the mid-seventies, income at Bass Brothers from oil alone fluctuated between $10 million and $15 million a month. Sid began applying his creative energy to a larger canvas—downtown Fort Worth. He eventually transformed the city’s decaying center with a fifteen-block complex that included renovated turn-of-the-century storefronts, cobbled streets, a starkly modern hotel, and two glass skyscrapers by Paul Rudolph.

As Anne and Sid Bass became more prominent in the community, they also became more reclusive. They flew on their own jets and appeared less often in public. After one break-in at the house and a holdup in their garage, they built a security station in front of the house and hired armed guards, three of whom patrolled the grounds 24 hours a day. Bodyguards started accompanying family members when they left the house, but the effect of the reclusiveness and the security was to make the community more curious than ever.

You don’t have to be in Fort Worth long before you get the impression that everyone in town knows that the house has five bedrooms and six baths; that there’s a butler, a cook, and two maids; that Anne drives a Silver Cloud; and that two new jets have been ordered, each with a bedroom and a dining room. Yet, if you ask anyone a direct question about the Basses, most people get nervous. That sort of nervousness occurs whenever one person controls an irrational amount of money. You can be the most sensible individual in the world, but when you come in contact with that person, you begin harboring irrational hopes that she will do something irrational herself—such as seeing your true worth and rewarding it. The flip side of that hope is fear, especially if you are dependent on her for your financial well being. With the exception of three or four people, no one in Fort Worth would talk to me—on or off the record —until Anne Bass had cleared it.

One day my husband and I were sitting outside,” says Anne Bass, her back still to the window, waving her hand toward a little seating area in the garden. “We were watching our children play, and I was thinking what a wonderful life we had. But with Sid doing such great things, I felt I still had to do something on my own.”

The thing she chose was philanthropy. In addition to supporting the Fort Worth Art Museum, Anne Bass had started contributing her time and money to the Van Cliburn Foundation, the Fort Worth Country Day School, and the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. Everyone at these institutions today is quick to praise her contributions. Anne Koonsman, the symphony’s executive director, says that Anne Bass is “nurturing,” that she has had good ideas for fundraising and building a board, yet she doesn’t interfere with the professionals hired to run the organization. Ted Sanford, the headmaster at Country Day, says that she is good at solving problems and has an eye for detail, and he points to the school’s grounds, which she had landscaped. Yet, even from her strongest supporters, there is an undercurrent of caution and an eagerness to defend Anne Bass that gives credence to rumors of her divisiveness.

A general perception has grown up that Anne Bass tended to dominate the boards she was on, that she had to get her way or she would quit. It has also been assumed that she was somehow responsible for the rapid administrative turnover at the Fort Worth Art Museum, where three directors and an interim director came and went within ten years. When people talk about the Basses’ contribution to the arts and their high standards of excellence, they eventually get to the “Bass body count” and the people who didn’t make the grade. Given that Anne Bass is only one person and one vote on a board of trustees, it is difficult to lay the blame for the departures directly at her feet. And given that people who work for arts institutions are extremely reluctant to be seen biting the hand of a patron and that Sid was the president of the board at the museum, it is difficult to discover exactly what happened at specific board meetings.

But it is fairly easy to see why Anne Bass has been perceived as a villain. If she was sure that she was right, she didn’t particularly care what people thought about her or how they felt. According to one of the departed museum directors, she made it clear that she “wasn’t running for public office.” Always a private person, she dealt with the attention by simply ignoring it. She was often curt with people who worked for her, and if things were not done to her satisfaction, she would throw temper tantrums. She didn’t speak to people she regarded as potential hangers-on, and worse, there were some people she saw regularly whose existence she refused to acknowledge because they didn’t measure up to her standards. If, for example, she had to deal with a professional partnership and she felt one partner was superior, she wouldn’t bother with even a display of politeness toward the other. She was interested only in the best, but in pursuing it, her own behavior was often anything but exemplary.

Recently, a man in Fort Worth connected with the arts was talking about Anne Bass, saying how much she had done for the city. Then, an expression moving across his face that would suggest gastric discomfort, he said, “I don’t know. We’re all pretty well educated around here. I’ve been to Mortimer’s in New York; I can get in the door. But whenever I talk to her, I come away with the feeling I’m not good enough.”

People from Fort Worth today buy apartments in New York the same way those West Texas ranchers built houses in Westover. It’s a stage of development. In older countries the rich usually have two addresses—one in the capital and one in the province they are from. Fifteen years ago people from Fort Worth weren’t comfortable going to New York. Now the city is practically an obsession.

As usual, Anne and Sid Bass led the way. In June 1983 they bought an apartment on Fifth Avenue. Sid’s business was keeping him in the city more and more. In addition to financial affairs, he was on the board of trustees at both the Museum of Modern Art and Yale.

The apartment they purchased—for the then record price of $5.25 million—overlooks Central Park, has fifteen-foot ceilings, the largest living room in Manhattan, and a master bedroom with a view of the park. To decorate and to help put together what has been described as “an important collection” of European antiques, they hired Mark Hampton, whom Anne had known slightly while growing up in Indianapolis. Again, perfection was sought. A Balthus for the hall. Monets for the dining room. For the living room, two huge Mark Rothkos that could rival the view of the city.

Talking about Anne Bass, Hampton praises her intelligence and stamina and as an example recalls that on trips to Europe she could spend four or five hours at a time walking through a museum. As he talks, it occurs to me that the average person is so fatigued in museums because he has to figure out how what he is seeing relates to himself, whereas what rich people are doing is really a form of shopping.

Long before buying the apartment, Anne Bass had become involved in the School of American Ballet. The involvement proved to be a spectacular entree to the city. It also led to a ballet-world scandal that had some New York society observers labeling Anne Bass a “hick.”

In 1978 Anne was asked to join the National Advisory Council for the School of American Ballet, the teaching institute for the New York City Ballet. Traditionally, charitable institutions in New York, particularly those that are most successful, have provided the service of social validation. To put it more bluntly, they take money and launder people. The ballet school, to avoid the problem of having too many nouveau riche patrons, had started seeking supporters outside New York.

For a patron, the school at that time was not considered glamorous. Moreover, no one at the school knew much about Anne Bass. Until the school’s first important fundraising gala in May 1979, they simply thought of her as being the “nice lady from Fort Worth.” She was asked to be one of the ten co-chairmen for the event, and according to Mary Porter, who was the school’s director of development, Anne was expected to bring in one table of ten guests at $200 to $500 a ticket. “Everyone was absolutely floored,” says Porter, who now lives in Houston, where she works for the investment counseling firm of Fayez Sarofim. “She brought thirty to forty people from Texas, plus people from Connecticut, California, and New York. Over fifty per cent of the guests were Anne’s. We knew she had money—everyone did, but so what? None of us expected the results we got.

“We all laughed at the office when her invitation lists came in. We couldn’t believe the addresses. There were people who lived on something called Old Spanish Trail, and there were a lot of cactuses and ranches in the addresses. Then, all of these people showed up, a lot in their own jets. We thought it was glamorous.”

It was also glamorous for the Basses. In the fall of 1979 they invited dancers Mikhail Baryshnikov, Peter Martins, and Heather Watts to their home for dinner after a performance in Fort Worth. Heather Watts was and still is a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. Baryshnikov and Martins were easily the most famous male dancers of their generation. Baryshnikov would go on to become the creative director of American Ballet Theatre, and Martins would succeed George Balanchine, the co-founder and the creative genius behind both the New York City Ballet and the School of American Ballet. “It was incredible,” Martins says, recalling the evening in Fort Worth. “We knew they were young and rich, but we couldn’t believe it when we got to their house. When we came in, there was an orchestra playing. It was . . . ,” he shakes his head, at a loss for words.

The Basses, particularly Anne, befriended Martins and Watts. Their daughters started taking classes at the school during the summer, and Anne and Heather eventually came to call each other “best friend.”

“I don’t think of Anne as just being rich, and she doesn’t treat me like a ballerina,” Heather Watts said recently over a beer and a hot dog at a cafe in New York. “I also think of Sid as a good friend, and like all of Anne’s friends, I hope he’ll come back. When the story came out about Sid and Mercedes in New York magazine, I called Anne and said, ‘I can’t believe how rich you are.’ I knew they were rich, of course, but that isn’t what our friendship is about.”

There was some question, however, about Anne and Peter Martins’ friendship after the news broke that Sid had not only departed with Mercedes but had had other girlfriends. Stories began circulating that the friendship was based on more than a love for ballet, but Martins flatly denies any romance. “Anne and I are friends,” he tells me, “and we sometimes go places together, but that’s all there is to it. It amuses us that people are talking.”

When I had the chance to ask Anne Bass about it, she said that it was ridiculous, particularly given Heather Watts’s longstanding relationship with Martins.

Watts and Peter Martins were stars. The way that Anne could participate in the world of ballet was as a patron, and the person who would play the most critical role in her development as a patron was Mary Porter.

In retrospect, it seems almost uncanny that Anne Bass met Mary Porter when she did. Porter had straight blond hair, and she bore a striking resemblance to Anne. After graduating from Connecticut College, Porter took a job as personal secretary to Lincoln Kirstein, who with George Balanchine had founded the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet in the thirties. She had started fundraising and had showed an extraordinary talent for it, but even after becoming the development director, she continued in her position as Kirstein’s secretary.

What every fundraiser needs is a great patron, and that’s what Mary Porter saw in Anne Bass. The school was going to celebrate its fiftieth anniversary in 1984, and Porter wanted to mount a $15 million fund drive to establish a permanent endowment. She knew that it would be a tremendous job and that Anne would be the perfect chairwoman for the campaign. In the fall of 1981 she and Lincoln Kirstein asked Anne if she would do it. Anne said no at first, but Porter kept talking to her about it; three months later, Anne agreed. “Once she said yes, it was as if she had gone to work at the school as an unpaid member of the staff,” Porter recalls. “She wrote letters, she helped with the planning, and she called people. We would set up meetings for her with prospective donors, prepare a dossier on the sort of things they cared about and what they would probably ask. Then she would take them out to lunch and try to get them to contribute to the school. She knew everyone at the school, and she wouldn’t accept anything that wasn’t perfect.”

At the school Anne Bass played a role larger than that of most patrons. She became something of a personage, a force unto herself. When Peter Martins describes her, he talks, as do most dancers, about the way she carries herself or, as he puts it, “the way she moves herself around.”

“When I was a little boy in Denmark,” he says, “the king and queen would come to the Royal Theater—to their theater—to make a visit. I was in the corps de ballet, and they would tell us that the king and queen were coming and that we had to behave in the hallways. When they came, when they walked through the theater, that’s what it was like when Sid and Anne would come here.”

Anne might have infuriated the secretaries who had to type letters over and over until they were right, but Balanchine—the genius in residence, the Picasso of ballet—called her “the golden girl from Texas.” The night before he died in 1983 she went to the hospital and sat on the edge of his bed. At the funeral she stood among the mourners. Alexandra Danilova, a teacher at the school who had fled Russia with Balanchine after the revolution of 1917, recalls watching Anne at the funeral. “In the Russian Orthodox Church we stand up. Unless you’re old and weak, we stand sometimes for two hours. At the funeral, I glance at her from time to time. People shift back and forth, stamp on one foot, then another. But she doesn’t move. She stands there perfectly still, beautiful posture. I count her as a dancer. She is disciplined like a dancer.”

By the time of the gala in January 1984, it appeared that Anne Bass’s life was going perfectly. Eight hundred people attended the party, which netted the school $750,000 in one night—more than three fourths of its annual budget. W raved that the Bass legions had arrived. According to Lincoln Kirstein, the Basses had replaced the Morgans and the Rockefellers as America’s premier dynasty. And Anne Bass was younger, richer, and prettier than most of the grandes dames she was compared with. Moreover, unlike many of them, she at that time had a husband who did not send her off alone or in the company of a walker.

The gala, however, was only one night, albeit the high point, in a two-year fundraising drive. By the end of the second year Porter had raised $10 million. Anne had established herself as a major philanthropist, and Mary Porter had made a name for herself as a fundraiser. Together, they set their sights on a new goal—$7 million to build dormitories and new administrative offices for the school.

The first indication that something was wrong came in February 1985, when Kirstein dismissed Porter as his secretary after sixteen years of service. No cause was given. It was agreed, however, that she could continue in her position as development director. In April Porter went to Houston, where she secured a $1 million verbal commitment from Louisa and Fayez Sarofim; she then went to Fort Worth, where Sid and Anne Bass pledged another $2 million. She returned to New York, and a week later Kirstein fired her as the director of development. When Anne Bass heard, she threatened to withdraw her financial support.

As observers look back on the events, they are divided into two camps. Lincoln Kirstein’s supporters say that Mary Porter and Anne Bass were making a power play, that they were trying to take over the school and planned to kick the 78-year-old co-founder out on the street. Anne Bass, Mary Porter, and their side deny the charges, saying they were only trying to meet the school’s financial needs. The first public notice appeared May 6 in the New York Times under the headline DISPUTE SPLITS BALLET SCHOOL BOARD. According to the story, written by Anne Kisselgoff, the paper’s dance reviewer, “Mr. Kirstein and his supporters . . . speak of what they call a ‘Texas takeover,’ because one of Miss Porter’s prime supporters is Anne Bass.”

The controversy (it was regarded as nothing less than a scandal in the dance world) played out over the next month in the Times. Porter was fired, and Kirstein was vindicated. According to one of Kirstein’s supporters in New York, “Anne Bass came off looking like a hick. She simply failed to understand who Lincoln Kirstein was. He not only founded the school and the ballet, he helped start the Museum of Modern Art. He was one of the people who helped make this city what it is, and you don’t just kick him out.”

Peter Wolff, one of Anne’s friends on the board, casts a different light on the situation: “Lincoln grew up in Boston, where his family owned the department store Filene’s. He went to Paris, discovered Balanchine, and brought him back to New York in 1933. But it was Balanchine who was the artist. Lincoln was always the patron. Lincoln saw Anne as another patron. Mary just got in the way.”

In the New York social world most people didn’t understand what had happened. All they knew was that somehow Anne had made a mistake, and that was enough for people to turn against her. In Fort Worth, according to a member of the art world, “people were jumping up and down because someone had finally stood up to Anne Bass.”

The telling fact, however, is that Anne did not leave the school and that her friends there stood by her. She is still on the board and was recently asked to join the board at the New York City Ballet at Peter Martins’ request. “Anne had the right to speak up when Mary was fired,” Martins says. “That’s why we have board members. We can’t just take their money and tell them not to speak.”

Anne, in the meantime, had not abandoned Fort Worth for the bigger stage of New York. In 1984 one of the teachers at the School of American Ballet happened to comment that Anne’s older daughter was developing very well in spite of the instruction she was getting in Fort Worth. The implication that Anne and her daughters were getting second-best was enough to set Anne off. The best meant Balanchine, someone from the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet. She called Martins and asked him to start looking for a teacher. In Fort Worth she rented commercial space in a new shopping center just off Interstate 30 and spent $300,000 of her own money to put in a dance studio. Then, at Martins’ suggestion and with his help, she hired dancers Nanette Glushak and Michel Rahn to come as teachers. When they arrived in Fort Worth, they had three students—Anne and her two daughters. Anne, however, had told them they could make what they wanted of the school and suggested that there would be other possibilities.

Anne’s actions were by no means a declaration of war, but the Fort Worth Ballet, a struggling company that Anne had chosen not to sponsor, surrendered anyway. Three months after arriving in Fort Worth, Glushak and Rahn were asked to become artistic directors at the ballet, and Anne was invited to join the board. “If I want to see good ballet,” she is quoted as saying, “it would be a lot cheaper for me to see it in New York.” But eventually she agreed, and since April 1985 the Fort Worth Ballet has received $280,000 in grants from the Sid Richardson Foundation, in addition to private gifts from Anne Bass. A resident company is now in place, many of the dancers from the New York City Ballet, and it is hoped that Fort Worth will become one of the leading regional centers for dance. Anne Bass’s patronage has made the ballet a going concern —one that other foundations and patrons are willing to support—but to truly succeed, the ballet will have to find its own audience. “We’ve established a good board of directors,” says Jane Brown, the ballet’s executive director, “and it’s important for all of us to know that we can survive without Anne.”

The sky has started to clear over Fort Worth. It’s bright blue with some scudding gray; a slight chill is in the air. I’ve asked to see the gardens, and Anne Bass is leading me along a gray slate path that isn’t quite wide enough for two. Straight ahead there’s a reflecting pond, where a Maillol sculpture of a voluptuous nude woman appears to frolic upon the water. To the right is a narrow alley of live oaks, their tops boxed, giving a European touch to what could almost be a Hill Country meadow in Texas. Steps lead down to a large formal rose garden, where there are hundreds of rosebushes, beds of herbs, perennials—more than I can take in. Beyond, there’s a large rectangular lily pond, then the orchid house, which though it is white steel and glass seems almost Victorian in spirit.

“This isn’t really the time to look at the garden,” she says as we pass the roses, “but you might as well see the orchid house.” When we step inside, we are enveloped by warm, moist air and a rich fragrance. “Ginger,” she says, indicating a long row of tall plants bearing white blossoms. “I brought back a little cutting on the plane from Hawaii, and that’s where all those came from.”

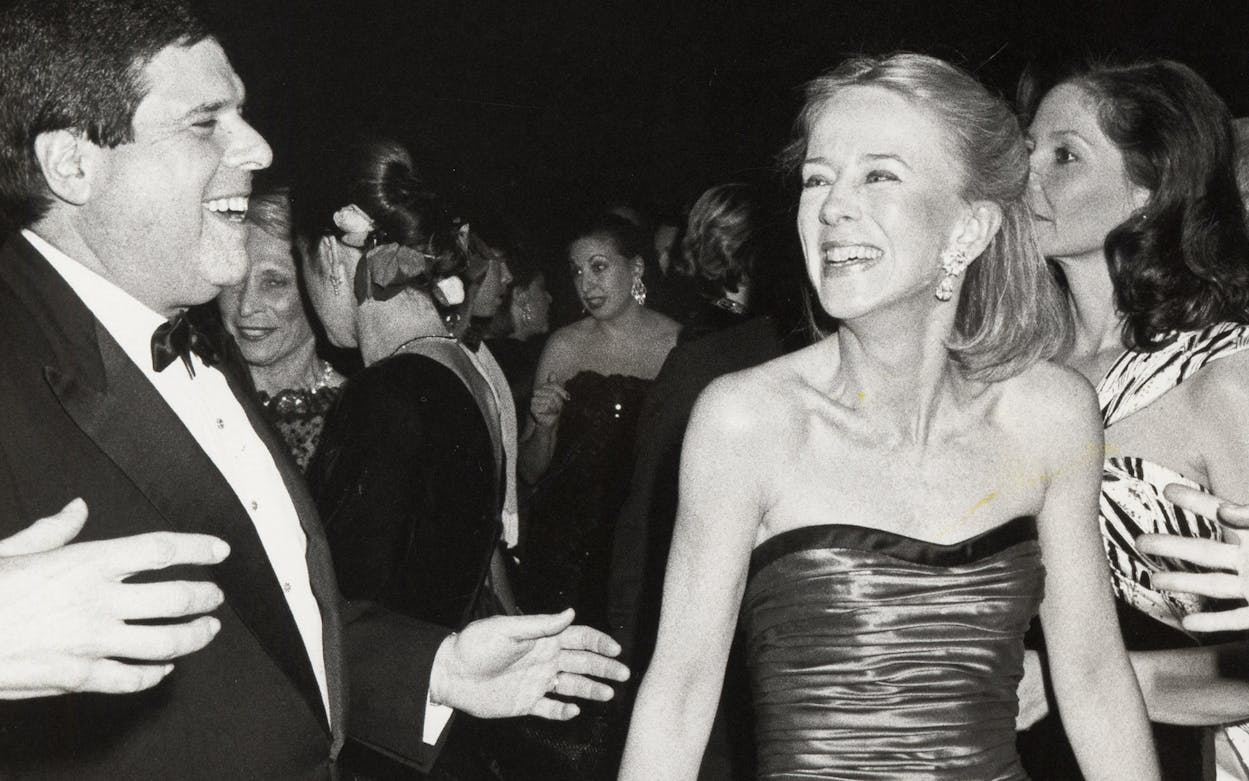

As we walk around, I keep wanting to ask what’s next, but I know from Anne Bass’s friends that she’s hoping her husband will come home and that like anyone in her position she can only wait with as much dignity and humor as she can muster. She had just pulled off a black-and-white dinner dance for the Fort Worth Ballet’s season premier. The event, named after a Balanchine ballet, was called “Who Cares?” and the irony was not lost on W, which ran photographs of Anne at the party and commended her for her stiff upper lip.

When we come to the end of the rose beds, she says, “Let me show you this,” and leads me down a path to an undeveloped part of the garden next to a creek. “This is going to be wonderful in here, if I can just figure out how to make the creek stop flooding.” She stands there a moment, imagining what it will be like, then we start back to the house.

“Growing up in Indianapolis, did you ever suspect your life would be so extraordinary?” I ask.

“My life doesn’t seem extraordinary to me. It seems very normal.”

“It does?”

“Yes, of course. It seems normal.”

“That’s too bad. I think you might be missing some of the pleasure.”

“Perhaps. Perhaps it seems normal because of those historical novels I read.” As we approach the house, we talk about books and she becomes animated, saying that she reads voraciously. “Botany and gardening books. My bookseller in London still sends me five a day, and I read everything I can get my hands on about ballet.”

“And fiction?”

“I’m halfway through Portait of a Lady, and I’ve started rereading Edith Wharton. What is the name of the book about that horrible Undine Sprague?” she asks, shuddering at the thought. “You know, she is that awful woman who comes out of nowhere and marries one man after another, trying to get to the top in New York City. I gave it to my older daughter to read, and when she finished it, she came and asked if there were really people like that in the world. I told her yes, that she might as well know now that there are people like that. But come inside. You can look at my library, and I’ll ask my daughter.”

We go through the house and up three flights of stairs to the library, where I wait while she disappears into another part of the house. Books line the walls; there’s a gray carpet on the floor and a view of the garden below. When she comes back, she says, “It’s The Custom of the Country.”

Later, I couldn’t help but think how ladylike it was of Anne Bass not to mention Mercedes Kellogg in relation to Undine Sprague, and how dramas such as this are indeed the custom of the country.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth