Frantically squealing and mooing, as if somehow aware of their destination, two cows and four calves lurch and bounce through an August Monday morning in the trailer towed by J. B. Haisler’s half-ton Chevy pickup. The cows are ten and twelve years old, the calves about five months, and none has ever before left the cozy 230-acres of pasture that now lie fifty traumatic miles behind them. The calves have been ready for market only a few weeks now, but today is the first Monday he’s had a chance to take them. Still, J. B. Haisler feels sure it’s a lucky day. It had rained most of the last week, the first heavy rain all summer, and it was his experience that “things just seems to perk up a bit after a good rain.’’

A tall, spare man whose plain, broad features have ripened during his seventy years, J. B. Haisler long ago learned to accommodate his life to nature’s whims. Born on a bottomland farm near the Brazos River, he has moved several times over the years but never away from the land or beyond his means. Riding in the cab of the pickup with his son and partner, Melvin, he gazes out the window and smiles as they drive into Fort Worth.

For more than forty years J. B. Haisler has been coming here to sell his hogs, mules, dried-up dairy cows, and foundered horses, and, for the past twenty years, his beef cattle. His herd back in Denton consists of one mostly Angus bull, unblooded but dependable, together with a few dozen Hereford cows and whatever progeny they might produce, and currently totals 85, minus the 6 in the trailer. He belongs to no great union or movement, no agricultural organization or federation more imposing than the Denton County Livestock Association. He doesn’t think of himself as a stockman, or as a cattleman, and certainly not as a rancher; in his own straightforward mind, J. B. Haisler is simply a farmer.

He is not much of a market strategist. He does subscribe to the Weekly Livestock Reporter and he listens for the market summaries on the radio, yet somehow his four or five annual trips always seem prompted less by the going price than by pressing needs: debts, children’s upcoming birthdays, visits from in-laws, or pure convenience. A year ago at this time J. B. Haisier sold his calves on a down market for 35 cents a pound and couldn’t pay his expenses on them. So, like most of his neighbors, he held back as many head as he could this year, feeding them on grain as long as he could, but the market didn’t start climbing until after Christmas and the winter brought the worst weather in years. In February his not-quite-yearling heifers brought only 45 cents a pound, his steers a dime more, and by then they were too light for him to recoup his losses.

Today, as they roll into Fort Worth, exiting the highway into the city’s old North Side, J. B. Haisler is mightily hoping his calves will make 70 cents a pound, and maybe even better. The calves, meanwhile, bleat and sprawl helplessly as the trailer rattles over the cracked and twisted North Side roads—meandering, bewildering, meeting abruptly in six-way intersections—roadways that bore cattle for half a century before there was a need for asphalt or stop signs.

Cattle have been lumbering through here since the 1860s. Back then, they were longhorns, bad-tempered and lately branded, as tough as the buffalo whose range they had inherited, free for the rounding up on the South Texas plains. They brought $3 each at Fort Worth, where the big trail herds gathered on the grassy, sheltered, and easily forded northern banks of Clear Fork, the third stream forming the Trinity River. The fort had once been the westernmost post in the U.S. Army, facing the alien prairie and restraining the Comanches with its one thunderous howitzer. That was before the cattle started coming and inspired a town.

Bedded down and quickly fattened for the journey, the cattle were then urged further northward by adventurous boys and addled, visionary men who drove them, mapless, toward St. Louis, Sedalia, Abilene, Wichita: toward the railroads threading back to the industrialized East, where a longhorn steer brought $40 in 1876, the year the railroad finally reached Fort Worth. Four million cattle had passed through town by then, in less than a decade, and six thousand people had a reason to live there.

The rails still pass through the North Side, often rusty nowadays, grass sprouting between rotting ties. The tracks cut across the dilapidated roads, passing over or below them, iron and asphalt bending to meet on the near banks of Clear Fork, like aged veins and arteries joined at the heart of an old way of life. J. B. Haisler stares quietly out at the fallow rails and derelict roads, the disheveled buildings of north Fort Worth, and he shakes his head. He can remember when this place was booming, exciting, downright fabulous, back when he was a strapping young farmer from Seymour, Texas, who came here to sell his first cow for $5.

That was during the Depression when a man didn’t get much for his animals, but, as J. B. Haisler recalls it, “you didn’t need a whole lotta money to raise a family back then.’’ He glances over at his son—one of three children he has raised and seen through college—and he wonders how a young man can make it farming these days, with everything so muddled and expensive. The little man can’t make it, he figures, unless his wife takes a job, bringing in wages instead of children, and J. B. Haisler firmly believes that “you ain’t really farmin’ if you ain’t raisin’ children, too.”

Then he looks back out at the shabby North Side, its futile thoroughfares lined with empty stores, until he begins to feel old himself. He can already see a few miles ahead the gutted wreck of the old Swift meatpacking plant, abandoned now for nearly a decade, crumbling slowly as its valuable antique bricks are stolen. Six tall stories of double-walled, close-fitted bricks, and sturdy as a tomb, the huge, ruined slaughterhouse dominates the view of the fabled Fort Worth stockyards.

But then, like a boyhood memory, comes the sound, at once mournful and petulant, of the mingled cries of yearling steers and failed milk cows, newly weaned calves and faltering bulls: the evocative dirge of the cattle pens. In a moment the smell arrives, too, a pleasingly familiar smell to a farmer’s nose—an odor as earthy and constant as himself. Smiling again, J. B. Haisler is convinced that today is a lucky day.

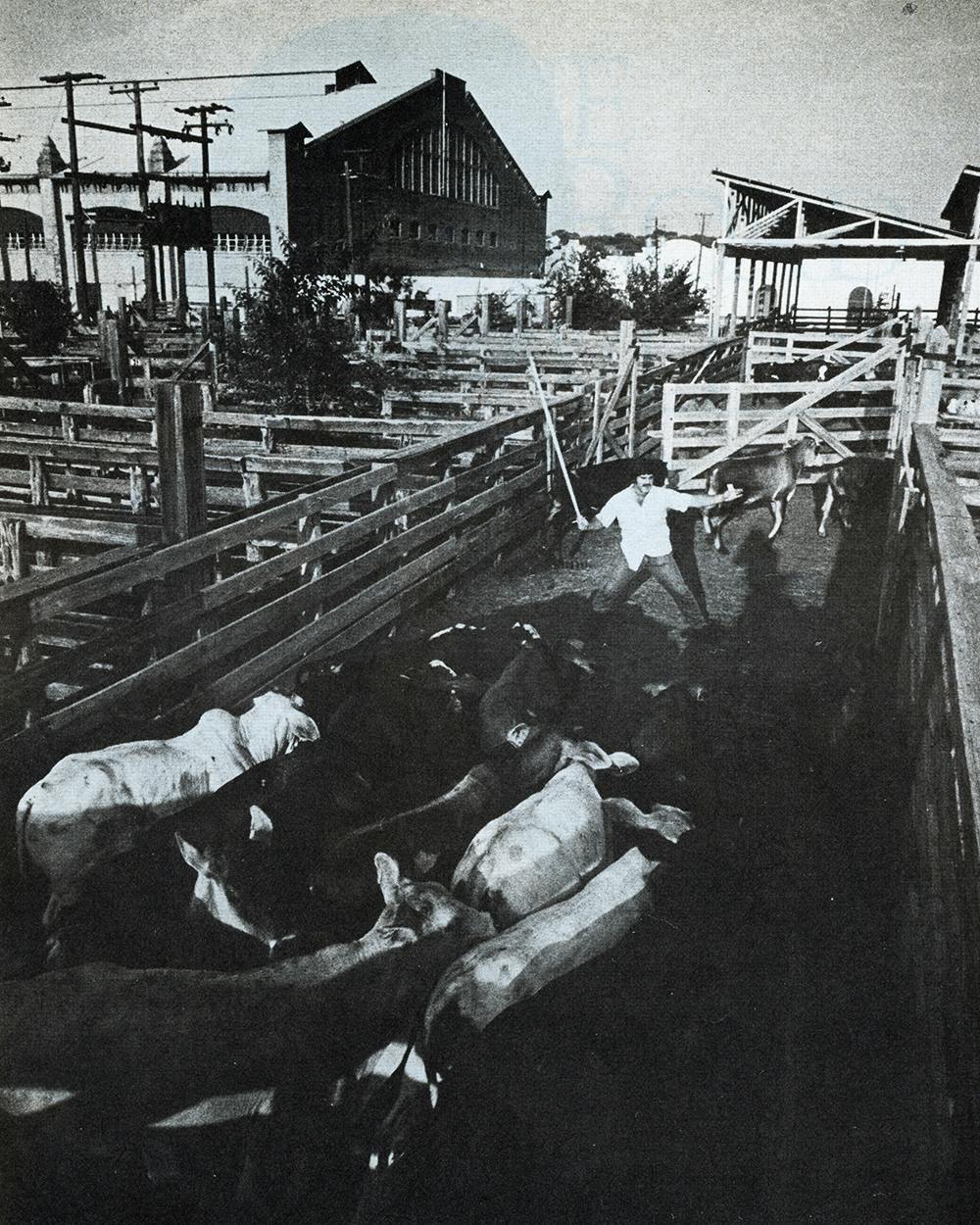

He turns the pickup down the back streets leading to the rear of the cattle pens, where the docking chutes are busy this Monday with men unloading small herds of eight or nine, rarely more than fifteen or twenty, head. A thin haze of rust-colored dust envelops the chutes, sweeping aloft in the hot summer air to drift above the pens like a sanguine fog. The pens are a riotous warren of corrals and stalls with clapboard alleyways passing among them, forming a wooden maze from the docking chutes to the auction barn. Each of the several hundred pens is furnished with a water trough and a bale or two of hay; each is built of rough cedar planks and floored with bricks. Virtually the whole of the stockyards is floored with these bricks: old-fashioned, hand-blocked, kiln-fired clay bricks, hard as stone.

Bricks were cheap when the Fort Worth stockyards were built, shortly after the railroad arrived, and nothing less could withstand all the hooves that rumbled through, bound for the mammoth packing plants of Kansas City and Chicago. For thirty years this was the major harbor on the Southwestern plains, the busiest junction of trail and train, the greatest of the cowtowns. By the end of the nineteenth century it was Cowtown, christened by cowboys and consecrated by their cows. Together they came here from as far away as Arizona or Old Mexico, coming each summer in numbers unsurpassed before or since to camp in the hills above Clear Fork and wait for room in the holding pens.

The bricks trap heat in the summer, especially in August when those 105-degree thermal waves come in off the simmering prairies. In the restless pens the body heat of the animals pushes the temperature even higher, stoking their frenzy and baking the air. In the old days, when the yards boomed and the pens were busy, strong men working here dropped from heat prostration, their jeans streaked white by the salt of evaporated sweat. A working saddle horse would lather up in less than an hour without so much as cantering, and the yardboys tending the pens needed three mounts each to spell a day.

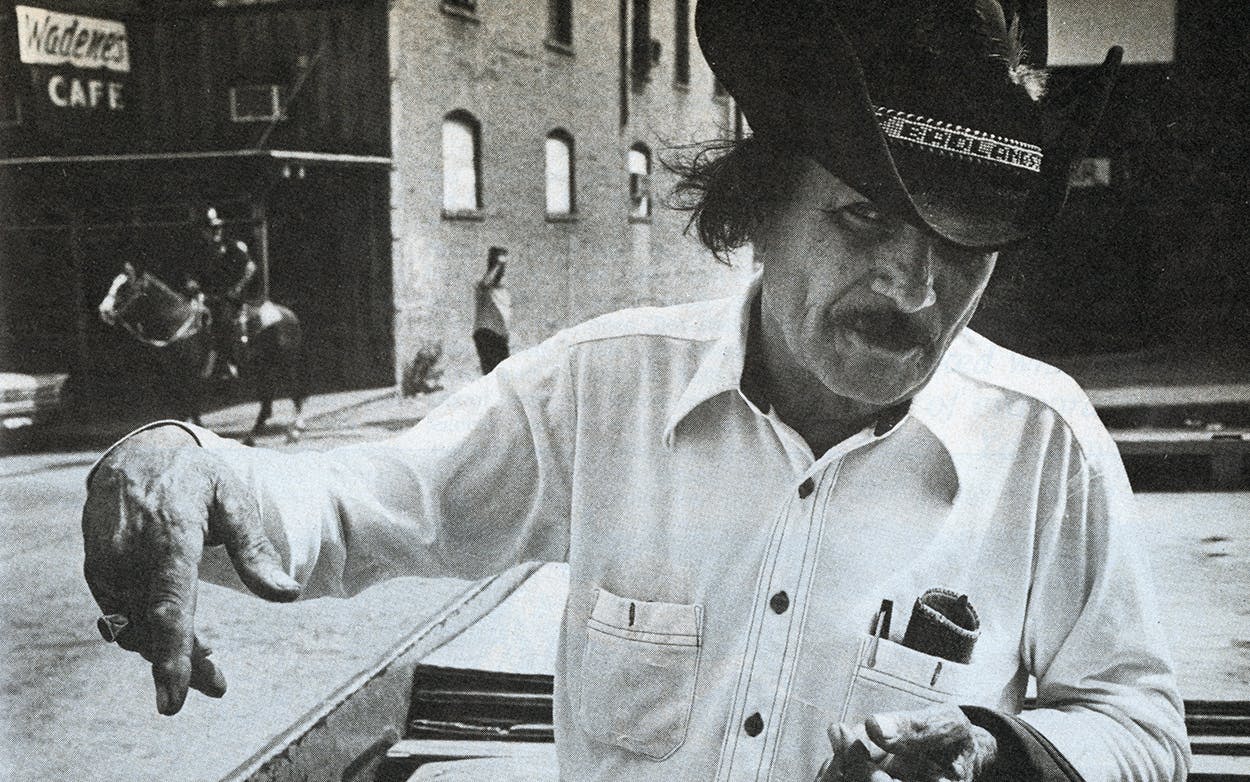

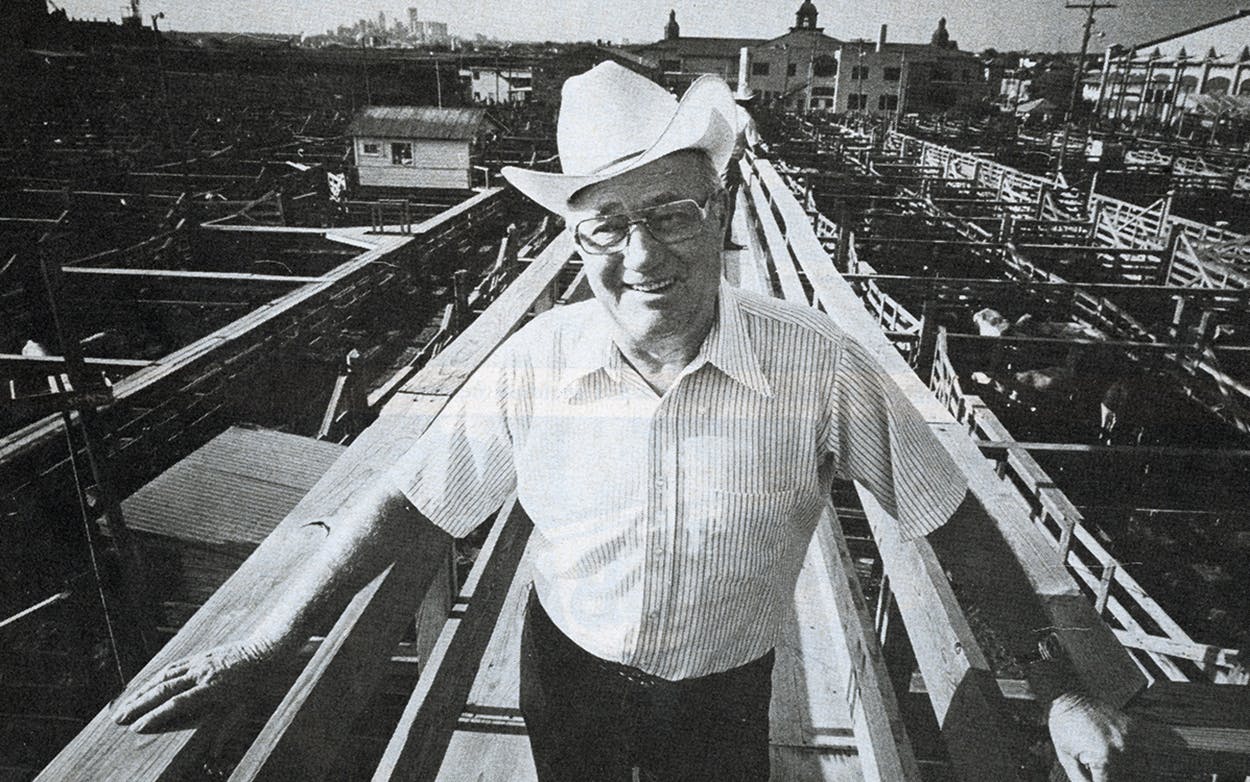

Leon Ralls was a yardboy then, 45 years ago, at the age of fourteen. At sixteen he was the prodigy of the yards, dealing in mules and hogs with men twice his age; at nineteen he brokered his first cow on the Cowtown market. Those were the “private treaty” days, when a freelance stock trader would shake hands with a seller and a buyer who had never met each other, yet would go into debt on the strength of the trader’s integrity. Following the Second World War, Leon Ralls came home from the Navy and, with his brother, started one of the 31 by then duly registered and regulated commission agencies on the Fort Worth Livestock Exchange: at that time, the Wall Street of the cattle business.

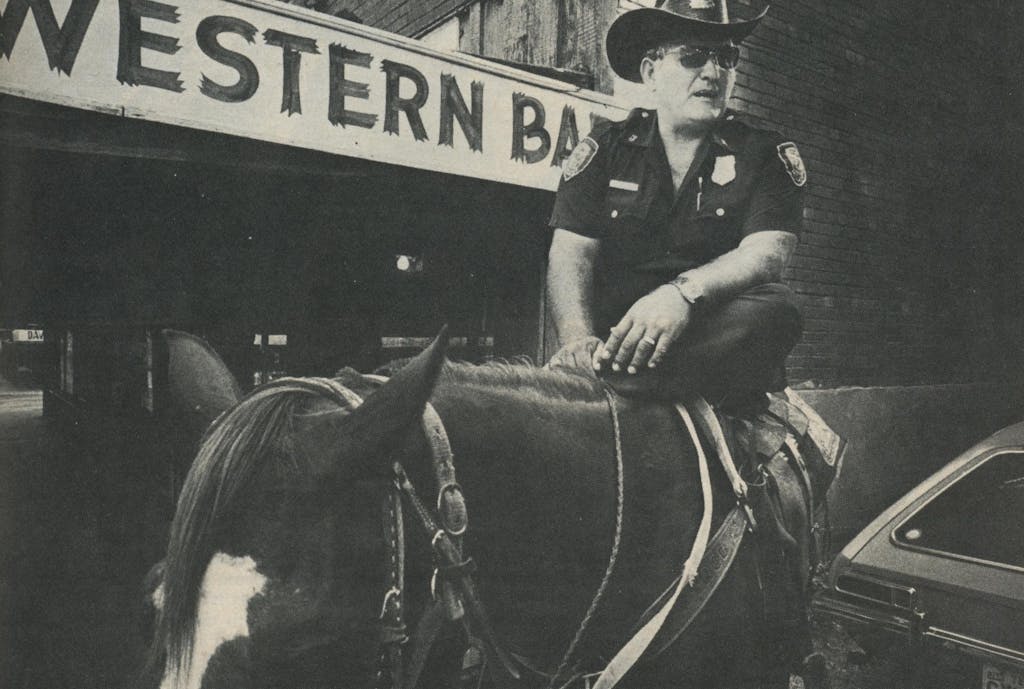

There are six commission agents left today and Leon Ralls is one of them. A small, pale, amiable man, he has the parched and sinewy look of desert mesquite but his alert eyes are soft and calm blue. By eight o’clock this Monday morning he has already broken into a sweat as he darts around the pens and back and forth to the docking chutes, where the cattle are being unloaded. Some of these farmers and ranchers have been his clients for thirty years and he greets them still with the same deliberate handshake, swapping rumors and taciturn pleasantries. From each he collects a pink receipt of ownership, which he stuffs unread in his coverall pocket, keeping tally in his head. Quickly assessing each small herd—judging their individual worth on the current market—he sorts them into auction lots of three or more that maximize their value, earning his fixed fee on the strength of his judgment. It is said in the cattle business that no one can tell more about a cow at a glance than a stockyard trader, such is the art of their profession.

Standing at the chutes with a small feedlot owner from North Texas, Ralls is appraising the man’s cargo of a dozen crossbred Brahman bulls, all full-grown two-year-olds. Brought to maturity on the feedlot, gorged on milo and protein pellets, they are somewhat flabbier than Ralls would prefer. Minus a few bargain roasts, mature bull meat goes entirely into sausages, frozen hamburger, and cold cuts. It is ground up with cereals and crushed ice for speedy curing (called “water-added” in the package ingredients) a process that loses more weight as the fat content of the meat increases. Hence the buyers for packing plants will pay better prices for firmer, leaner animals. The only other buyers of mature bulls, are short-term bull raisers. They can graze the fatter ones a couple of months to lean them out, then try to sell them to the packers for more than what they paid; thus, their profit, as in capital gains, is made on the market spread, and they bid on the market as much as on the animal.

In about two minutes, Leon Ralls has inspected the bulls and reckoned his options. His safest bet, the tight market strategy, is simply to auction them in three lots—the fat ones, the lean ones, and the rest—assuring strong bids among each group of buyers at least once. But Ralls, with a rodeo gleam in his eye, instead bets a hunch and divides the bulls into four lots of three, the fattest paired with the leanest, the lots weighted equally and inclined toward flabbiness. He is betting that the bull raisers, properly tempted, will gamble on the rising market to bid up the packers on all four lots, and so inflate the price a bit.

Tumbled from their trailers and down the chutes, the bulls are abruptly separated, marked on their flanks, jostled and poked. In what must seem to them a pandemonium of insults, they are then rudely harried down the lanes by shouting, whooping yardboys mounted on noisy little motor scooters and equipped with electric cattle prods. Operating the gates like pinball flippers, they finesse the animals from alley to alley, between corrals and through the maze to whatever pen Leon Ralls has assigned them. Shunted into their appointed blind alleys the bulls mill around in circles, carom off fences, then finally settle down to join the others in some loud and resonant complaining.

Any cow that isn’t eating is puzzled by its own existence: having evolved for thousands of generations by the grace of man, cattle have a tendency to be suspicious, when they aren’t being fed. They grow restive, make each other nervous, stomp and fume. In the sweltering morning air the dust rises slowly above them and spreads downwind. Spreading more invisibly but further is the smell, the raw and powerful compound aromas of fresh straw, animal sweat, scooter exhaust, adrenaline fevers, stale urine, hay, and the several scents of cattle manure—the oddly pleasant odor of grass-fed dung, the gaseous stench from feedlot bowels, the pungent diarrhea of newly weaned, panicky calves—all of it baking on the hot, dry bricks. Reaching still beyond the smell is the baleful sound, tremendous and urgent, like an amplified moan, more than a wail but less than a prayer. In the dim universe of a cow this is purgatory, that place where virtues are weighed against flaws, the awful interlude between the meadow and the slaughterhouse.

These are not show cattle, those haughty champions pictured in the agriculture sections of Sunday papers, spoiled on mineral supplements and acres of grama grass. These are rather the unwashed masses of common cattle, scrambled of breed and motley in appearance, unregistered, lackluster, and now disowned. Cast into their respective lots, milling and squalling, they range in age from three months to twenty years and include both sexes and the neuters of both. They are mangy, smelly, surly, lice infested, too lean or too fat, often lame, and always abysmally stupid. Dumber than mules and lazier than dogs, they could never survive on their own: this is what gives men the right to ill-use them. They are not altogether docile and predictable, however, for somewhere out among them is the one-ton crossbred Brahman bull, black with brindle flanks, that today will make a cripple of old Leon Ralls.

The stockyards really started booming after the turn of the century when the capitalists arrived. The newly simplified scheme of refrigeration promised to eliminate the cost and hazard of transporting beef on the hoof, but first the meatpacking plants had to move closer to the hooves. And so canny old Gustavus Swift and his dapper competitor, young J. Ogden Armour, son of the founder of Armour & Company, journeyed down by private train to scout Fort Worth. The town fathers, who were merchants by trade and peddlers by nature, predictably endeavored to hard-sell the dignitaries on their growing city: lavish receptions were held, proclamations made, Stetsons presented. But then old Gus Swift, white-haired and yellow-bearded, a wily tyrant, gruffly remarked that Dallas had a bigger river and nicer trees.

The mortified boosters reacted with a prostrate offer of free land and water, a tax haven, and whatever cash it took to build a slaughterhouse, all in the forlorn hope that one of the moguls might be lured away from Dallas. With becoming dignity, both accepted the offer immediately and returned to Kansas City and Chicago, leaving their attorneys to deal with the jubilant storekeepers. In 1903 Swift and Armour opened gigantic, extravagant packing plants right across from each other at the foot of Exchange Street, conveniently adjacent to the greatest terminal market in the history of men and cattle. By the 1920s, two million head of cattle were sold and killed each year in the Fort Worth stockyards, plus a million hogs and 500,000 sheep.

Even the horse and mule barns were fireproof concrete and Pittsburgh steel and floored with bricks like everything else. They were built for $300,000 and described at the time as “among the finest sales stables in the world.” And these, of course, were for slaughterhouse horses—spavined, lame, stove-in—200,000 of them a year.

At 5:30 every morning the shift whistle blew at the Swift plant, a fierce metallic shriek that stirred the neighborhood and raised from the other end of Exchange Street a melancholy, guttural echo. Harried along by yardhands, the cattle and hogs, balky and churlish, would start moving down the quarter-mile road, while the gentler sheep followed blissfully after a Judas goat. For most of four decades the enormous plants ran at capacity six days a week and, whenever they could make crews for the killing rooms, on Sundays as well. They were run, for the most part, on immigrant labor. Eastern European newcomers who worked hard, didn’t talk back, and never met any cowboys—except perhaps in the bars at night, where they all went looking for trouble.

The North Side became notorious for its quick-fisted bars and edgy pleasures; it was where you went looking for the best illegal liquor or the highest poker stakes, for swing bands, dice games, bank robbers, bronc riders, streetwalkers, all kinds of bet takers, for the home of Bob Wills or the hideout of Bonnie and Clyde. By the mid-thirties the stockyards area had acquired the hell-bent nature and bad reputation of people who live in the vicinity of death, waking each morning to its shrill and demanding whistle. Smelling blood in their sleep, they arose with adrenaline already pumping, and they lived very hard in an old-fashioned style.

“In the old days, people they come here from all over Texas,” sighs J. B. Haisler. “Some’d come in from Oklahoma, Louisiana, New Mexico even. Wasn’t many places you could sell your animals back then, not if you needed real money for ’em.

“Pens was a whole lot bigger then, too. Sometimes it looked like most of the cattle in the world was here, carryin’ on like crazy. Was hard to think what you had was worth much in the middle of all that. They didn’t have no auction then, either. You’d meet up with the agents and the buyers out by the pens, settle your business right there.”

Like all luxuries, Depression beef was a buyer’s market and the only buyers that mattered were the purchasing teams from Swift and Armour, who fanned out over the yards, sparing no effort to outflank each other, but always stopping short of paying more. “People be runnin’ all ’round out there,” recalls J. B. Haisler with a distant grin. “They’d be all talkin’ up a fuss, yellin’. Animals hollerin’ ever’where. You didn’t hardly know what you got till you went to the office to get your check.”

Leon Ralls has a wry memory of laughing—but then most of Exchange Street laughed—when the first scattered local auctions, which would change the cattle industry forever and doom Fort Worth’s monopoly, were organized after the war. The prices were a shade lower than in Fort Worth at first; nevertheless, they caught on quickly in places like Amarillo, San Angelo, Nacogdoches. Changes on the land were becoming obvious, imperative, inevitable. Advances in food technology—refrigeration and processing—compelled yet another dispersal of the meatpacking plants, while postwar America was also developing a new taste for corn-fed beef.

There is an axiom in the cattle business that it’s always cheaper in the long run—since cattle are such awesome gluttons—to take them to their feed, instead of the reverse. Thus, Panhandle feedlots came into being when Americans began to want the kind of well-marbled, juicy, and tender meat that only a super-rich diet can develop, even on an animal as lazy as a cow. As the demand increased, the feedlot owners proved willing and able to outspend the packers for the prime young steers they intended to feed.

Breeding and feeding became sciences more than labors; new equipment became an investment and a tax write-off at the same time, instead of just an expense; the cattle business became complex, fragmented, specialized. Buyers proliferated in the cattle market, but not in Fort Worth.

Swift and Armour fought against it right to the end, but an auction barn was opened in the Fort Worth stockyards in 1960. Tucked belatedly into a corner behind the grandiose Exchange Building, built of ordinary cinderblocks to resemble one giant cinder-block—square, drab, unpainted—the auction barn is the cheapest and ugliest building in the entire stockyards, and, nowadays, the only one that can pay the rent. The regular Monday auction still gets underway at nine o’clock, promptly, reliably, and stubbornly.

By a quarter till the yardboys are moving the cattle in the turbulent pens, running or scooting from gate to gate, opening one, closing another, almost like valves. The worst thing that can happen in the pens—Leon Ralls has lectured the yardboys often—is to lose the identity of the cattle, to mix up the lots, since that is the trader’s sole means of influencing the auction. Concentrating thus on the brightly colored ear tags, instead of on the animals, the yardboys cull and maneuver them carefully, deftly, mechanically.

Sensing movement, the anxious cattle grow more unruly, moan louder. They fidget and complain, pace about, stomp and kick and crowd one another, panic, stampede in place. None of them aware of anything but noise and paranoia, they run sheerly for the sake of fleeing, crashing into fences that sometimes swing open suddenly to deflect a few into different pens or along new alleys. Heads down and straight ahead at all times, turning as required, the cattle lumber through the maze like boxcars in a freight yard: screeching and colliding, witless and manipulated. In due course and in an orderly manner they will all wind up before a huge green door, closed at the moment, waiting for Leon Ralls to signal it to be opened and for the auctioneer to call their numbers:

“All right now, boys, this next lot fourteen got some old retired milkers, six fine old Holstein dairy cows cornin’ up here now let’s say good mornin’ to the ladies, lot fourteen this is I say good mornin’ ladies . . .”

The big, green electric door jerks open, a steel gate slams behind them, a buggy whip pops overhead, and the six flustered ladies jump forward, completing their escape from the holding pens to the auction arena. Leon Ralls is awaiting them in a wide dirt semicircle holding a long, wooden staff such as men have used to herd cattle since they first found a reason to. After a last quick look he speaks to the auctioneer, who speaks into his microphone:

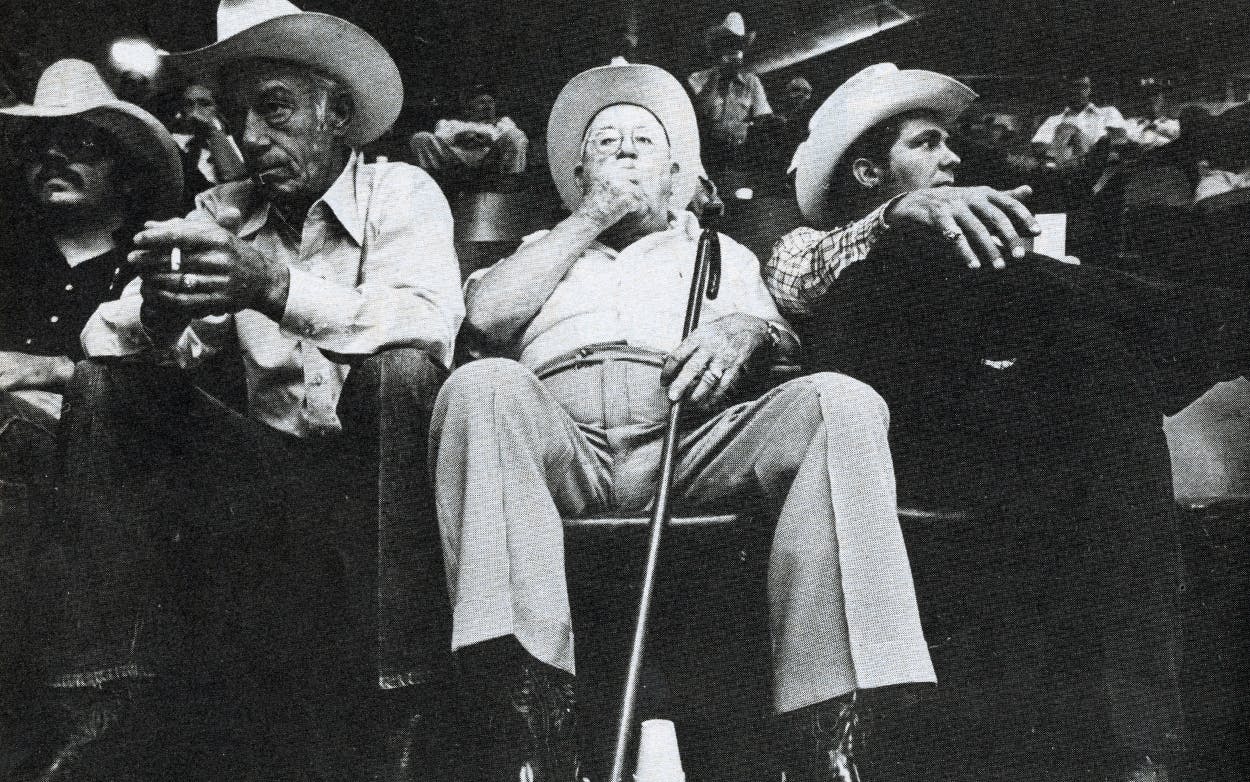

“Okay we’re gonna pick it up at thutty-five for these ladies, lot fourteen this is an’ we’ve got thutty-five, I say thutty-five, five-quahtah, I see five-naff, now five-naff, six it is, hey now six-a-quahtah, quahtah, quahtah . . .” Rising back away from the low-railed auction ring are twenty-odd tiers of frayed and battered theater seats, some five hundred in all. About two hundred are occupied this Monday by stark-looking men with angular faces and leathery hands, smelly boots, and tan straw Resistol hats. Many have bought Styrofoam cups of bad concession coffee, drunk it off quickly, and are now slowly refilling the cups with amber tobacco spit; others merely spit on the floor. About fifty of the men are buyers and the rest are smiling: they’ve all heard by now that barely 1500 head of cattle were brought to auction this morning—the fewest in a year and less than half the summer average—assuring the sellers of premium prices.

Sitting halfway up in the bleachers, J. B. Haisler chuckles softly to himself. It’s because of the rain, he figures. You can never tell how a rain will affect the market. During the arid summer, farmers had been selling off their calfless cows and weak steers in order to stretch the brown grass for their stock herds and money cattle and because they were encouraged by the steadily rising market. Now, with the promise of greener pastures, most have chosen greedily to hold back everything, to fatten their cattle a while on free grass. Had the rain been lighter or the drouth longer, had the market been shaky, they might just as easily have decided otherwise.

Quietly pleased with his good fortune, J. B. Haisler sits back and watches the awkward Holsteins lurch around the arena. Bred since the Middle Ages for their milk and their stationary habits, dairy cattle, widehipped and swaybacked, are pathetic creatures when they try to run. As the six old cows wheeze about, their full sacks jiggle and bobble, which evokes a scowl from an ex-dairyman like J. B. Haisler. “It’s them milkin’ machines does it,” he mutters. “Got those suction cups on ’em. Some folks hook ’em up and then forgets to come back ’n’ unhook ’em. Ruins the bags where you can’t do nothin’ but sell ’em.”

The ruined ladies are sold at $38.50 a hundred pounds—about $400 each—to a small local meat packer for low-grade hamburger, probably dog food. The packinghouse is the last reward of every calf born in America, irrespective of breed, sex, career, or term of service, but the packers no longer dominate the cattle market. In today’s specialized, cost-effective cattle business it isn’t unusual—in some parts it’s normal—for a farmer to sell his weaned calves to a grass-rich rancher who pastures them until their quadruple stomachs can handle the protein saturation of the feedlots, whence they will be sold again to cattlemen who “shape” or “tone” them before finally selling them, sometime in their third year, to a slaughterhouse. At the Fort Worth auction on an average Monday, less than one buyer in eight is a packer.

The wonder is that any of them come here, to an irrelevant railhead hundreds of miles from the irrigated Panhandle Plains where the feedlots sprawl (Amarillo’s auction is four times larger than Fort Worth’s these days) and not much closer to the major breeders of South and Central Texas. Armour & Company shut its Fort Worth plant in 1962 in favor of smaller plants in handier places, while tight old Gus Swift’s giant slaughterhouse ran a few years longer on obsolete equipment and low wages—paid to blacks and Chicanos—before it too was closed and razed. They will tell you around the stockyards that the ruins smoldered for three years afterward, the smoke rising like dark steam from the heap of blood-red bricks, but that’s the kind of talk you get around the Fort Worth stockyards.

Some of the men around here will tell you proudly that they were present in the stockyards Coliseum just up the street—the birthplace of indoor rodeo—the first time anyone ever rode Five-Minutes-to-Midnight. Forty years later none of them remembers the cowboy’s name, but with rheumy eyes they can still see that legendary coal-black, cartwheeling horse. Some few others can recall Bonnie Parker holed up in the corner room of the old Right Hotel, waiting for Clyde, when she shot the first country fool who took her for a hooker. She then proceeded to party all week, and no one would report her.

Most of their memories are more prosaic but equally vivid, bound to this place by the same long, gritty tradition. There isn’t a man in the auction barn who can’t recall in sharp detail his first trip to Fort Worth, remembering clearly the first cow he sold here and for how much, and usually where the money went. This is Cowtown, after all, always has been, and, because they are men who respect endurance and value roots, their coming here seems natural, unremarkable, even practical. The drive to Fort Worth is a ritual older than they are, which is reason enough to make it worthwhile.

Creatures of habit but pilgrims in spirit, these are headstrong, durable men who have outlived their time and refused to admit it. They aren’t modem white-collar cattlemen, profit-minded and management-trained; they’re, rather, grimy, workaday cowmen who tend to distrust marketplaces generally but feel comfortable here. Fort Worth remains a major terminal market for cattle—among the nation’s ten busiest—because they can’t believe it isn’t, and by faithfully delivering their cattle for auction they make it one. Set in their ways and proud of it, they sit up in the bleachers of the auction barn and talk earnestly about the weather, rubbing their hands and nudging each other, as nervous as penny gamblers. With stern squinty eyes they stare down into the ring, where a mob of young heifers is surging back and forth, bawling and shrinking en masse from the tap, tap, tap of Leon Ralls’ wooden staff.

It is the largest lot of the day, 34 heifers recently taken off grass, all at least one year old and 700-plus pounds apiece. A hundred days in a feedlot will put another 300 pounds on each and Ralls has sorted them accordingly. The feedlot buyers would much prefer young steers, which can gain 30 per cent more weight on the same diet, so they don’t ordinarily haggle over heifers. Selling them all together is the quickest way to dispose of them and shouldn’t affect their price.

“Got fo’ty-two, fo’ty-two, two-naff yet two-naff, three! Now three, that’s fo’ty-three, three, three-naff . . .”

Using gestures as spare as their words, the men in the bleachers lift an eyebrow or a lone finger, nod or shrug imperceptibly to indicate their bids. The bidding occurs invisibly to everyone but the bidders themselves, the auctioneer, who sings out prices from his pulpit behind the ring, and Leon Ralls, who stands just below him surrounded by heifers. His back is against the shield, a shoulder-high protective screen built out from the auctioneer’s platform and resembling the barrera in a bullfight arena. Despite the ten-ton crowd of milling hooves around him, Ralls doesn’t bother to get behind the shield. Sweeping his staff in a low quadrant before him, knowing the hysterical heifers would sooner trample each other than challenge it, he doesn’t even look at them; he’s too busy watching the bidders.

“Now I’m seein’ fo’ty-seven, fo’ty- seven, c’mon give me seven-a-quahtah, quahtah, I see seven-a- quahtah . . .”

A month ago these same heifers would have sold at 40 cents a pound, but today, with so few cattle at auction, the bidding approaches choice steer prices. Obligated to longterm contracts and costly overhead, facing a market they expect to continue rising, the feedlot buyers are forced to shop for whatever is available. Ralls also notices a few bids coming from large-scale breeders who, apparently reading the market likewise, want the heifers for breeding stock. Spotting the trend, Ralls keeps the animals running even when the bidding lags, allowing the buyers to look and worry some more. Following his lead, the auctioneer adlibs melodious nonsense to cover the gaps and sustain the momentum of the price advance. Not until the price reaches 50 cents does Ralls signal his acceptance.

Sitting among the nonbidders, J. B. Haisler slaps his boney knee and hoots. “Wheew boy, fifty cents and they ain’t a calf in the lot,” he says, poking the man next to him. “Last year you’d of got maybe two bits on a bunch of heifers.” He leans forward rubbing his hands together, a smile easing across his plain, weathered face. ‘‘Not a calf in the whole bunch!” Weaned calves are a cowman’s most profitable item, and J. B. Haisler hasn’t seen a calf yet today that he thought was as good as his. ‘‘I knew this was gonna be a lucky day,” he declares, then sits back wearing the small, warm grin of an honest man ready to claim his reward.

Down on the arena floor, Leon Ralls has slipped behind the shield to flip through his lot cards while three big crossbred bulls charge around the ring, all hot and bothered and mad, seeing red everywhere. Their bovine anger is as absolute and simple as their fear, the same blindness in another color, and it quickly reverts to fear the moment Ralls steps away from the shield after passing their card to the auctioneer. Firmly tapping his staff on the ground, he is instantly their master, a man herding cattle.

All three bulls, squat, blocky, and cream-colored, are of Charolais stock with about an eighth part Brahman, revealed by their high, humped backs and floppy ears. The Brahman blood usually makes them somewhat feisty, but Ralls knows they’ve just come off the feedlot so he isn’t too concerned. Cattle in a feedlot do nothing but eat, sleep, and defecate, bloating themselves for a year or more on an endless blessing of “hot feed,” a potent blend of whole grains, shelled corn, and protein pellets. Texas cattle are fed more grain and less corn than Northern cattle—it’s the reason for their meatier flavor—but a feedlot anywhere is a cow’s nirvana. Fed into a constant stupor, they grow not merely accustomed, but oblivious, to noise and commotion, narrow confinement, and people who goad them. Thunder and lightning won’t even rile them so long as they’re eating. Tranquilized by gratification, they come to maturity with soft, tender muscles and dull senses, sluggish instincts and indolent ways.

Turned out of paradise only this morning, the bulls are too demoralized to be quarrelsome. Ralls waves his staff at them and jabs them, now and then whacking one across the haunches, and they just wail and bolt like yearling heifers, bewildered and hungry. The bulls in fact are so thoroughly cowed that Ralls hardly pays them any mind, watching his audience instead and following the bids. This is the first of the four slightly overweight lots he sorted earlier, and his strategy of playing the packers against the bull raisers works better than he could have expected. In the end, the bulls are sold to a packer, but not before the ranchers have pushed the price to 48 cents a pound—generous for cannery animals, which usually dress out to less than 50 per cent of their live weight.

Moving quickly to keep up the auction tempo, Ralls ducks behind the shield again as the green door opens and the next lot of bulls charges madly into the arena. All have the flop ears and trademark humps of crossbred Brahmans—maybe one-quarter Brahmans—each weighs nearly a ton and has blunt, stubby, foot-long horns. Two of the bulls have the brunet coloring of Hereford stock while the other is an Angus cross, black with brindle flanks, but the Brahman blood is what gives force and passion to their anger.

“Don’t much like them Brahmers,” drawls J. B. Haisler, squinting down from the bleachers. “People say they’s real hardy, grow real fast, but I don’t care. They’s mean. Jes’ plain mean. I don’t want no kinda cattle I can’t let my grandchildren be ’round. I don’t think they like people.”

Named for the highest caste in the Hindu religion, Brahmans are the sacred cattle of India, holy animals incarnated differently but no less specially than men, the same life spirit in another form. Tough and adaptable, they were brought to Texas a century ago, and they took easily to the hot Southern plains of the old Cattle Kingdom. Thin-skinned and hairless, they never travel north—even an eighth-part Brahman rarely goes as far as Colorado—but are kept in warmer country, where they grow faster, healthier, and stronger than any other breed of cattle with less care and feeding. They out-breed the others, too. Their blood can be diluted 31 parts to one and the back will still be humped, the ears will still flop, the Brahman spirit will predominate.

They have, however, responded poorly to being profaned, to say nothing of being eaten. Exalted partly for their gentleness in India, Brahmans in the Americas have become famous for their meanness. Even hard-bitten dryland ranchers dislike the breed, introducing the blood to their herds only in cautious amounts several times removed from pure Brahman stock, and only from competitive necessity. Brahmans are the bulls that rodeo cowboys try to ride—for about eight seconds if they can—and the breed that, more than any other, recalls the character of the rangy old Texas longhorn.

The crossbred bulls in the arena haven’t got a full set of Brahman genes among them, of course, and it shows. Snorting as they rush across the ring to avoid Ralls’ jabbing staff, the bulls pile up together at the end of every pass, spin around fiercely, paw the ground for a moment, then flee back in the other direction, keeping just beyond reach of the stick. Bred for submission and fed into dependence, their anger dissolves into panic even when they’re cornered. Ralls stands calmly at ring center, tapping his staff almost absentmindedly, not even worried enough to watch them. Thus, he is probably the only person in the auction barn who doesn’t see the black, mottled bull stop abruptly in the middle of the ring, as if seized by an inspiration, turn with its head lowered to face the trader full-on, grunt once, and charge instantly.

As the bull lunges from ten feet away, Leon Ralls drops his staff and leaps for the shield, scrambling up it. He is a spry and wiry man, and only his age prevents him from escaping. He is five feet up the wall, nearly over it, when the bull hits him in one smooth, solid movement that never wavered from the moment of decision. The blow is so sharp that both bones of Ralls’ left leg snap loudly, breaking cleanly. As he tumbles to the ground, fighting to crawl behind the shield, yardboys spring from the gates to harry the bull off, but the animal makes no effort to charge again. Tossing its head and bellowing, it struts twice around the ring and runs out the open gate to the weighing station.

J. B. Haisler takes it all in rather impassively. “Jes’ like a Brahmer,” he observes finally, conclusively. The men in the auction barn all lean back and stretch, hitch one leg across the other, spit in their cups or onto the floor, and watch patiently as Leon Ralls is carried out of the ring. The trader is placed in a folding chair just outside the arena rail, his leg propped awkwardly, then he signals for the three bulls to be brought back. A pair of yardhands—posted discreetly behind the shield—assume the task of running the cattle and Ralls proceeds with the auction while he waits for the ambulance.

Displaying no trace of its recent bravado, the brindle-flanked bull and its two lot-mates resume their flight around the ring, quailing before the yardhands’ tapping staffs, behaving again like normal cattle. Up in the bleachers, apparently unmoved by the outburst of bovine temper, the men look on with the same rapt attention as before, solemn as judges in an election year, the bidding starts up anew and rises swiftly to the price of the previous lot of bulls and these, too, are sold for hamburger. Wasting no time, Ralls calls for the next lot, shuffling hurriedly through his cards, waving signals to the auctioneer and keeping things moving.

By the time the ambulance arrives, Ralls has sold a dozen more lots and his face is ashen, his lips blue. The attendants give him oxygen and cut away his pant leg, pack the swollen limb in a plastic, inflatable cast, then he stubbornly pushes them back and calls for more cattle. The attendants roll in a bed and stand around perplexed while Ralls directs a few more sales: one of J. B. Haisler’s cows turns up in a lot sold at 38 cents, almost a nickel more than he had hoped for. Twice more the medics offer the oxygen mask and attempt to argue, but Ralls just ignores them, as does virtually everyone else. The men in this building are as hard to distract as they are to impress. When he’s finally loaded on the bed and wheeled out, Ralls is nearly in shock, but another agent takes over and the auction never slackens, so no one notices. These are single-minded men, here in Cowtown to buy and sell cattle, attentive to their purpose and not very curious.

J. B. Haisler’s calves are sold shortly after noon in a lot with a few other calves, all indistinguishable from his in appearance but inferior in his opinion. They are bought by a Panhandle feedlot buyer for 76 cents a pound, top price for the whole summer, equal to $650 per calf, the best price J. B. Haisler has ever gotten for his calves. Quietly grinning, he and his son Melvin go down to the office to collect their check, then they walk outside to the parking lot. It is early afternoon by now. Most of the cattle have been sold, and most of the farmers are starting to drift outside, heading for home. There isn’t much to keep them here any longer.

The Haislers climb into their pickup and drive off down Exchange Street, rattling over the bricks, turning past the fabled stockyards Coliseum—once the Westminster Abbey of the Cattle Kingdom—past the barns, now mostly unoccupied, and crossing abandoned railroad tracks. The road bends erratically, unpredictably through the North Side, passing by the shuttered bars and bankrupt stores of the old rowdy neighborhood. Downtown Fort Worth moved upwind fifty years ago, across the river to the south, and the downtown banks all red-lined the North Side in the fifties, stifling its development, as if trying to forget it.

Just before reaching the highway that leads back to Denton, J. B. Haisler rolls down his window and looks back again toward the stockyards. All he can see for certain is the crumbling, dark red shadow of Gus Swift’s slaughterhouse, but faintly, very faintly, he thinks he can see the dust swirling above the cattle pens, he can even smell the pens, and if he listens closely, devotedly, he can still hear the wailing cattle. And he smiles. Once again, he tells himself, it’s been a lucky day in Cowtown.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- Cowboys

- Cattle

- Fort Worth