This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

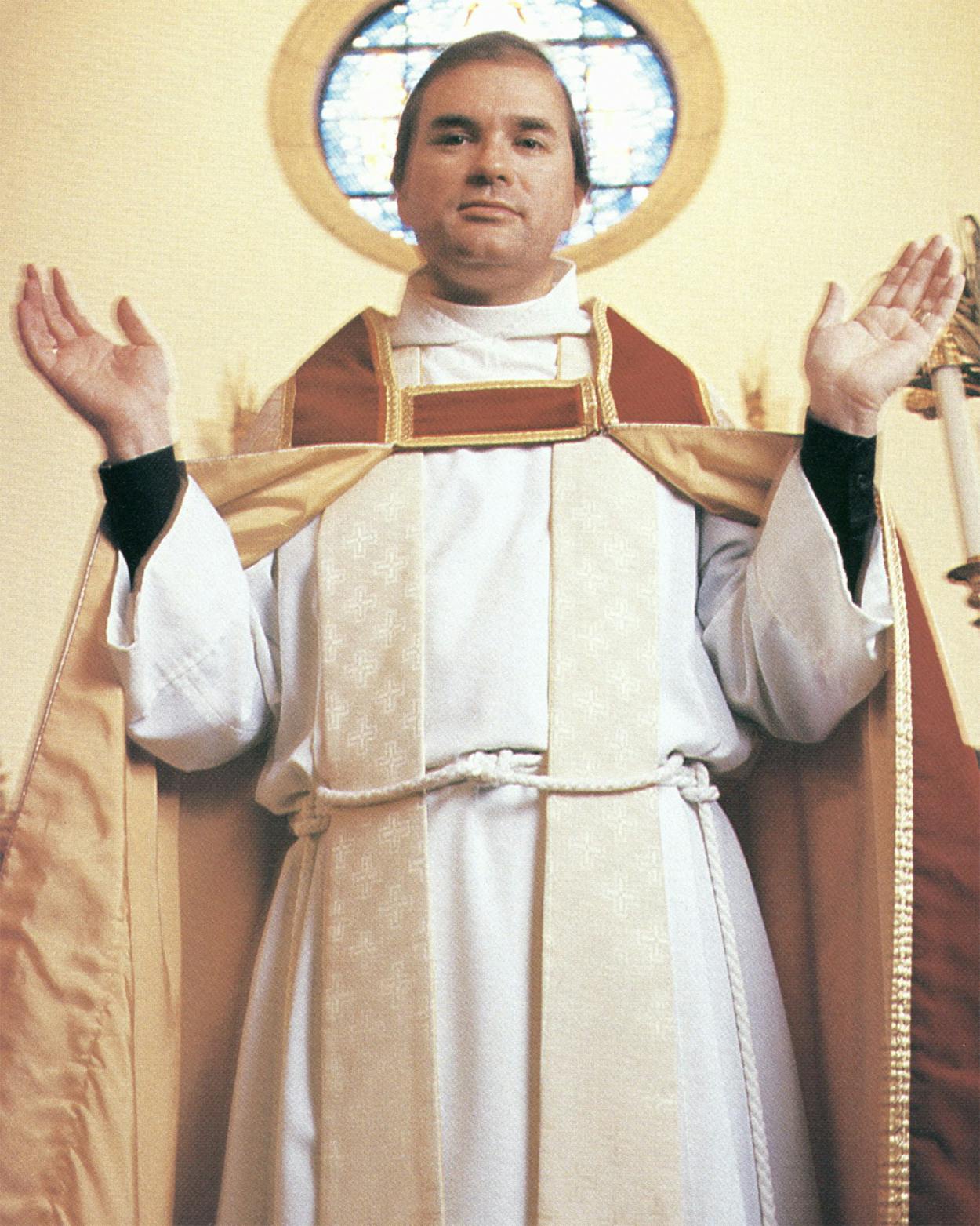

Father Jeffrey Walker, 42, is handsome in an Irish sort of way, with a broad face that brightens often with laughter. The rector of Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church in Houston for the past seven years, Walker likes to think of himself as a humble parish priest. He laughs, lunches, prays, and parties with his parishioners. But as soon as he opens his mouth, you realize that “humble” is not the word to describe this man of the cloth. “Easter is the Jeffrey Show,” he says. “I get to wear an outfit the pope would like to borrow. I’ll walk down the aisle looking like your grandmother’s sofa.” But it’s not just Walker’s wisecracks and irreverent remarks—and he is full of them—that make the priest on South Main Street an odd mixture. He favors a conservative, High Church style of worship, and when he talks about religion, it’s with an old-fashioned emphasis on God rather than some New age psychobabble. Yet Walker is committed to serving his community and has taken heat over the years for being too liberal (he brought in the church’s first female priest and initiated a ministry to AIDS sufferers). Some priests might shun the controversy that such extremes stir up, but Walker enjoys the limelight—both in and out of church. His active social life has gotten him into trouble with some of his older parishioners. Most of the flock, though, are confirmed devotees, many of whom first encountered him at a party.

Leslie Davidson, a residential architect, met Walker and his wife, Liz, at a wedding reception at the posh Warwick Hotel. Kit Wallingford, a lecturer at Rice University, says, “I was at a party, and I couldn’t help noticing him. He was a young priest, and he didn’t exactly fit meekly into the crowd.” And Lan Bentsen (son of Senator Lloyd Bentsen) and his wife, Lynne, met Walker when he introduced himself as the drummer who had played in a band at one of Lan’s fraternity parties back in the sixties. “Now he’s a great friend,” says Lynne. “Parishioners want him at their parties because he’s so funny and up-front. Jeffrey is the kind of guy who’ll tell you there’s a giant zit on the end of your nose, whereas another priest might just pray it would go away.”

What Walker lacks in pious demeanor offstage he makes up for in ceremonial splendor when he’s “on.” He is a ham and plays the part of the priest for all it’s worth. “It’s a toss-up who likes to get dressed up in robes more, Jeffrey or Qadaffi,” jokes Peter Papademetriou, an architect and Rice professor. But theatrics aside, Walker believes that religious symbols can touch people spiritually, in a way that intellectual understanding cannot. As many churches have stripped services of liturgy and ritual, they may have thrown out the baby with the baptismal water. “With his chanting and all that incense, the service is positively medieval,” says James Key, an ophthalmologist. “But once he’s out on the patio, he’s very much a twentieth-century man.” Walker’s church, wedged between Rice University and the Medical Center and flanked by two art museums, draws an intellectual and cultured congregation. The people who attend are the types you would expect to spend their Sunday mornings reading the New York Times and eating croissants, not scurrying off to formal nine o’clock services.

Walker drives to work each morning from the newly remodeled Georgian-style house the church owns in West University Place, a manicured residential area close to downtown. He passes through Southampton, an urban neighborhood where many of his parishioners reside. Its ivy-covered brick houses and gnarled live oaks lend the area a feeling of gentility. Once the province of old Houston families, the neighborhood has shifted over to doctors, lawyers, architects, and Rice professors. Residents like to think that taste, rather than money, defines the place now. The people who live there put great stress on original artwork, gourmet coffee, and European vacations. Jeffrey Walker fits snugly into this newly defined parish because he is one of them. And he is as ubiquitous in it as holy water at a benediction. “I am a village priest,” he says. “This just happens to be my village.”

It is not so much “village priest” as “yuppie priest” that comes to mind when describing Walker, however. He may tell jokes, but he is never tasteless. His parishioners like him precisely because he has nothing in common with the electronic preachers of the eighties. He has charisma without being a charismatic. He is hip without the hype. He won’t tell you that the key to happiness is to let Jesus into your life or to have a personal experience with God. And he is apt to roll off a joke about Jim and Tammy Bakker.

On the Tuesday before Easter, Walker has already started turning down dinner invitations and canceling breakfast meetings to make room for his busy agenda. He begins his day in the office behind the church, meeting his secretary with calendar in hand. During Holy Week, Walker’s dance card gets overfull. He is popular not only at weddings, funerals, and baptisms but also on arts committees and at charity balls and birthday parties. “He shows up where you’d least expect him,” says Lynne Bentsen, who sees Walker frequently at social functions, such as the Ronald McDonald Silver Salute or the River Oaks Tennis Tournament. “He’ll walk up in his tuxedo and his collar, and we’ll say, ‘Don’t you know the Nehru look is out, Jeff?’ You’ve got to terrorize him before he gets his jab in at you and asks if a piece of material is missing from the back of your dress.” Walker is on the board of the Alley Theatre and numerous other organizations, has been an auctioneer and host for public television fundraisers, and serves on the mayor’s task force on drug abuse. He is a member of the River Oaks set’s Tejas Breakfast Club and is a regular speaker at ladies-club luncheons. People still remember the time he said grace at one such River Oaks luncheon, then announced, “You know, of course, that those of you who have already started eating will go straight to hell.”

In response to criticism that he is too social, too visible, Walker jokes that his missionary work is converting the heathen of South Main. But as he lunches at Ouisie’s—a neighborhood cafe with wooden tables and a chalkboard menu of fish, grilled meats, and select wines—it’s a little hard to tell who’s converting whom. Regulars greet him with evident affection. He stops to chat with U.S. district judge Woodrow Seals (“Hello, your sirness”), and a Rice professor by the window waves hello. He spies a waitress doing a crossword puzzle and tells her that 1 down is “salad days.” Walker says, “When people in my parish see me here, they know I’m a part of their life. People need to see that I do the same things they do. I’m a person. We don’t all live in Christendom anymore.”

Elouise Cooper, the restaurant’s owner, stops by Walker’s table, and the two of them reminisce about old times, when Walker first started hanging out at Ouisie’s and they drank more herb tea and fewer martinis than they do today. Back in 1976, Walker gave Holy Communion at Ouisie’s to a few close friends who said they didn’t want to take a regular’s place in a pew at Christmas. This cozy, rather cliquish ritual has been a tradition ever since.

Walker was born in 1944 on Christmas Day (“So in a way, I was born into a family business”) and grew up in West University Place, a few blocks from where he lives today. When he was eleven, his father died of cancer, an event he describes as pivotal in his decision to become a priest. While still a teenager, Walker played drums in country club bands. Before he graduated from high school in 1963, he worked in a men’s clothing store, and within three years of graduating, he was an owner. At the age of twenty, he married Liz Hall, his high school sweetheart (“We’re very close. In fact, we’re joined at the hip”).

Liz and Jeffrey were living in a four-bedroom house in the Memorial area of Houston and already had two children when Walker decided, with Liz’s encouragement, to finish college and enter the seminary at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. “As early as high school I knew that I thought about things more than other people. When I was growing up, priests were always in our house, in our kitchen drinking Scotch, telling stories, having fun. It never dawned on me when I became a priest to be something different from what they were,” Walker explains. “They were the ones who told me my father was dying. They were a model for me. Working in business, I felt like I wasn’t using the gifts I had.”

It has turned out to be a deft career move. The same suave manner that made Walker a successful musical performer and salesman now make him a successful priest. He draws people who are coming back to church after long absences, and if they come for a sense of community rather than for worship, that’s okay with him: “I don’t check their motives at the door. After all, they pay me to go to church.” More than half of his congregation of two thousand drive more than twenty minutes to attend services. “We’re all members of Jeffrey’s fan club,” says Kit Wallingford.

But Walker’s distinctive style has had its price. Over the years, parishioners who couldn’t accept his unorthodox approach have left for more-somber pastures. Pious sorts don’t take kindly to their parish priest’s calling the eucharistic wafers “fish food” or making jokes about the Holy Ghost. And even among those who stay, some think that Walker is a bit of a social climber, that his secular calendar doesn’t leave much time for tending his flock. “In order to be in the public eye, you give up some other things. Jeffrey is a little guilty of not taking care of his sheep, but he’s there when you need him,” says Larry Neuhaus, a real estate developer whose son died of cancer. Others have left because they think Palmer has become too High Church since Walker has been rector. Mostly, though, the people who don’t take to Walker are those who find him flip. “Some people see his humor as a way of distancing himself from people,” says artist Deborah Rylander. But Walker believes that laughter, like faith, is a way of dealing with life’s incongruities. It’s learning not to take yourself too seriously, a message his high-achieving congregation wants to hear.

On Easter—the day when the church pulls out all the stops—Walker is cloaked in a red velvet robe trimmed with gold brocade, greeting people before the regal procession begins. Trumpets, timpani, and trombones play as everyone rises to sing “Hail Thee, Festival Day!”—a hymn that strikes a chord of nostalgia, even when heard for the first time. Steven Fox, an architectural historian at Rice, vested in the blue and gray robes of the verger, leads the way, followed by acolytes bearing candles and incense, then the choir in wine-colored robes, and finally Walker and two assisting priests, passing the wooden pews and white lilies on their way to the altar. The event is deliberately textured with layers of sounds, smells, and sights of Easters long ago. In his sermon, his voice booming and echoing off the high ceilings, Walker makes a reference to Nietzsche and tells his audience that our society’s most pervasive tragedy is the illusion that we are in control of our lives. As the liturgy progresses to the singing of “Jesus Christ Is Risen Today,” Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby, a member of Palmer since he served as an altar boy there forty years ago, sings along in a scratchy baritone. On the way out, the Hobbys secure Walker’s promise to stay for the luncheon following their grandson’s baptism the next week. “We see Jeffrey quite a bit socially,” Hobby says.

The tendency is to dismiss a priest like Walker, with his wisecracks and heavy social calendar, for not fulfilling our expectations of a holy man. But in fact, he does deliver. The jokes are gone when he helps parishioners through crises, as when he recently comforted a mother after the delivery of her stillborn child. And his work with the AIDS ministry—organizing volunteers to spend time with terminally ill patients—has been a prompt response to a tragedy that reaches beyond his parish boundaries. Walker’s popularity comes from being the right man in the right place at the right time. Religion has always adapted itself to society. Walker’s style of ministry wouldn’t work in the ghetto, but Mother Teresa’s approach might not translate outside Calcutta either. “It may sound glib, but I don’t think there’s a separation between spiritual and everyday life,” says Walker. And if everyday life in this slice of Houston means dinner parties, luncheons, and charity galas, so be it.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston