“Mommy, who is the little Lord Jesus?” my three-year-old son asked me last December, pondering the chorus of his favorite Christmas carol, “Away in a Manger.” It was a question that has a simple answer in many quarters of the world, but not in our home, where I was chagrined and left speechless. I wish I could tell you that the complicating factor is Sam’s father, who is Protestant, but that is simply not the case. The truth is that if I had had a proper answer for my son, I might have resolved the central issue of not just Sam’s upbringing but my own. As it is, his was not a question but history calling a note. By Jewish law, the son of a Jewish woman is a Jew; with Sam’s birth and Sam’s life, the time has come for me to decide whether my ancestors’ faith will be abandoned or renewed.

To tell you that I am a Jew is both a truth and, to some, a shading of it. I grew up in a home where we did not practice our religion. I cannot answer the simplest questions about the Jewish faith, I am an awkward guest at Passover seders, and I feel an almost overwhelming discomfort upon stepping inside the temple of my youth. I went to school on Yom Kippur, the holiest of Jewish holidays; my family had Christmas trees. Yet I resent it when I am expected to join grace in Jesus’ name, and I feel my jaw tighten at the slightest anti-Semitic reference. Conversion to any other faith is out of the question. “My family is very assimilated,” I have told people for years, without really contemplating the meaning of the phrase. It means, of course, that I belong everywhere and nowhere, that I am a comfort to non-Jews and something of an affront, a failure, to those more religious than I.

It also seems natural to me that in this age of multiculturalism, as others clamor to preserve their singular histories, I have been drawn to my own story of loss. Approaching forty, I still have something of a child’s view of religion. In spite of all the horrors committed in God’s name, a part of me still longs for the religious teachings that were absent from my childhood. I know nothing of the agony of religious crises, so that in my idealized world, I imagine meaningful rituals that connect past and future, family members and friends, in times of joy and pain. When, I wonder, and why did my family lose track of that need? That anti-Semitism is in the headlines again gives my quest a darker tone.

I often suspect my family’s loss has to do with Texas, its myths and its demands. “Are there any Jews in Texas?” I am still asked by people on the East Coast; I still meet contemporaries who came from the only Jewish family in this or that small Texas town. In just a generation or so, we have ceased to be exotics. Some would inspect my past and surmise that, having come here twenty years after Texas became a state, my mother’s family was so eager to embrace the New World that the family faith became a casualty. But to me it is not so simple. When I look back over time, I see that each generation wanted to be Jews and each generation wanted to be Texans, and in their own way they tried to strike a balance so that both identities could be passed on. Mine is the story of the price we paid for trying to have it both ways.

WE HAVE TROUBLE FINDING THE CEMETERY. It is not because my parents do not know the near East Side of San Antonio, a hilly neighborhood of tidy frame houses and sturdy poplars that has been mostly black for generations. I suspect we are uncomfortable in this place partly because we buried my grandmother here just two years ago and the empty spaces beside her in the family plot seem far less innocuous than they once did. But it is also because the Temple Beth-El Cemetery is the only place where we are isolated solely by our religion. If you are not Jewish, you are not buried here.

It is a pointedly elegant cemetery, understated in the way of old money. Stones are large but not ornate, refined but not simple; mausoleums are quietly appointed with fine antique fixtures. The old city cemetery that runs for blocks nearby is run-down, with broken headstones, renegade mesquites, and unruly grasses. Temple Beth-El’s is a world of boxwood and crape myrtles pruned seasonally, leafless sidewalks in the fall, vividly green grass year-round. It tells you that, even in death, this is a community that will not let down its guard.

Joskes, Oppenheimers, Strauses, and Halffs are buried here, the builders not just of San Antonio’s German Jewish community but of the city itself. The Russian Jews they so disdained are buried in their own cemetery across the street; this place is as exclusive as any old private club. In a shady corner to one side of the cemetery lie the graves of two people, Simon Frank and his wife, Regina, who were born in Germany in 1825 and 1832, respectively. I do not know when exactly these people came to Texas and can only assume that they were fleeing the anti-Semitic dictates that were a part of the revolutionary chaos of the 1840’s. I do know their arrival marks the beginning of my family’s life here. Simon and Regina Frank were my great great grandparents.

My family has never kept detailed histories. Letters have long been lost, and photographic albums end abruptly, their pictures marked with the vaguest of captions, assuming in part that the bearer would always know, would always remember. What I know of Simon Frank I know as generalized history: that he probably began life here as a peddler, like so many German Jews to whom mercantilism was the only career option. He adapted quickly to the rules of the frontier. Being a Reform Jew, he didn’t have to worry about keeping kosher or closing his new, small store on the Saturday Sabbath, San Antonio’s biggest market day. He could not have gone to synagogue because there was not yet a synagogue to attend. This was not a time to adhere to Judaism’s strictest laws: I suspect that what Simon Frank found in Texas, and particularly in San Antonio, was a freedom he had longed for yet had barely been able to imagine. San Antonio was then a wide-open city of Catholics and Protestants, Mexicans and Anglos—who would have cared that he was a Jew? On the frontier, men like Simon Frank were a valuable commodity: educated, cultivated, hardworking. He was needed to build this New World.

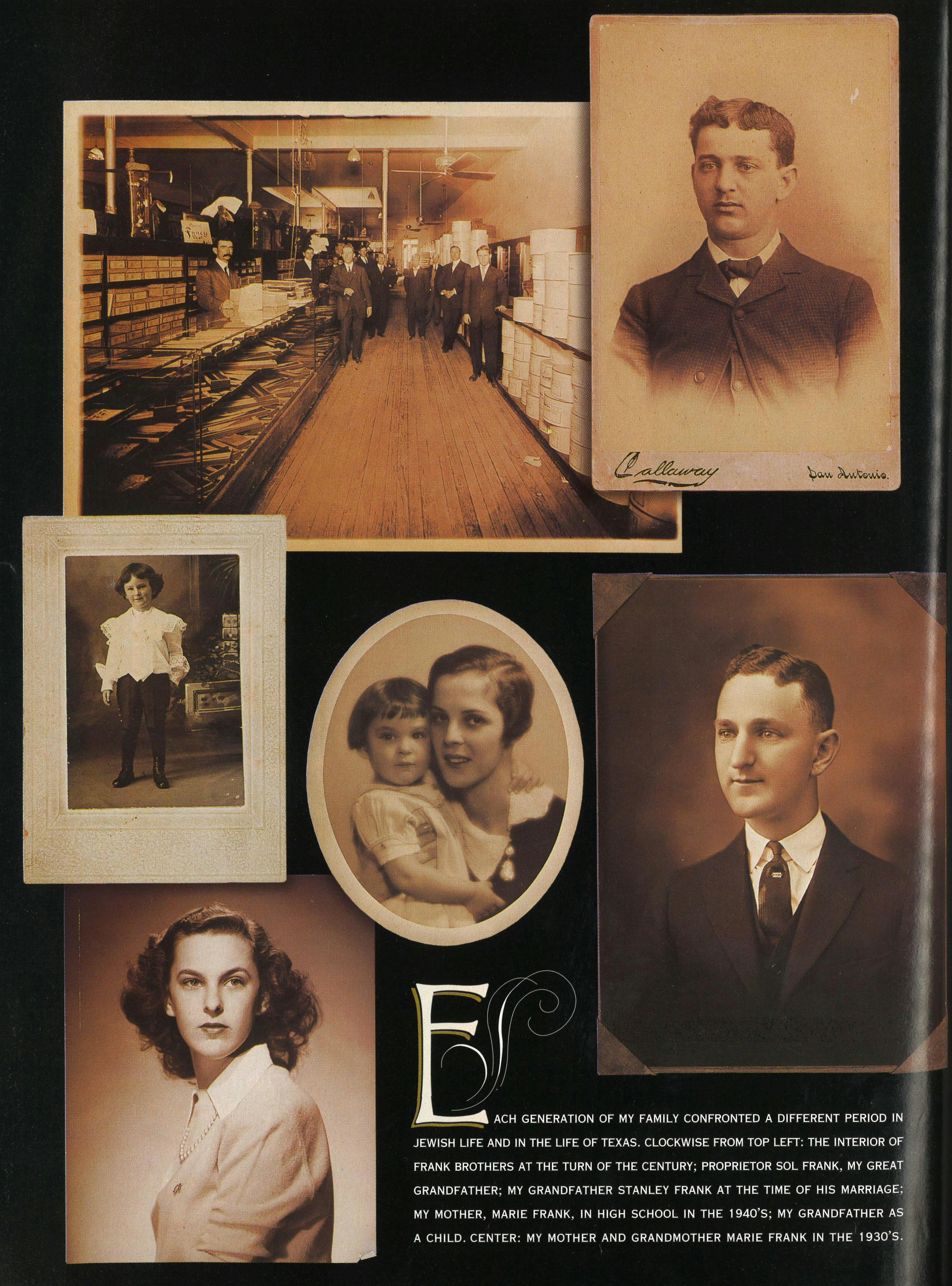

And build it he did, or rather his sons did. Simon Frank had five, and in 1893 three—Emil, Gerson, and Sol—turned Simon’s small dry-goods store into Frank Brothers, which featured fine men’s clothing. It was Sol, my great grandfather, who appears to have been the de facto head of the business: Born in 1865, he worked in the store from the time he was fifteen. The Encylopedia of Texas, a local Who’s Who published in the 1920’s, lists him as “one of the most prominent merchants of the Alamo City. ” By then he had become part of a small but firmly established Jewish community; once secure in San Antonio, they began to formalize the religious services that had, up to that time, been held casually in people’s homes. These were the people who were devout enough to build the first Temple Beth-El, in 1874.

What seems clear to me is that while Sol Frank felt obliged to practice his religion, his passions lay elsewhere. God could be more easily identified in a bolt of cloth or a growing balance sheet, proof of his progress in the New World. “Mr. Frank’s Church affiliation was with the Temple Beth-El,” the Texas encyclopedia notes, using language helpful to the assimilation process. “He was always an active member and Church worker, regardless of the fact that his business cares were heavy and much of his time was necessary to his great establishment. ”

In photographs of the store, it is possible to see nothing less than the civilization of the frontier. Frank Brothers was then located at Main Plaza, near the courthouse. From a contemporary perspective, it does not look very elegant—boxes of suspenders are stacked willy-nilly in glass cases, hatboxes that line an entire wall reach to the ceiling. But the wood floor is worn from traffic, the salesmen are smartly dressed, and high atop the back counter stands an elegant motif: A handsome leather suitcase is topped with a jaunty walking stick and a plaid golf cap, one after another, as if it were a reflection repeated in a mirror, as if it had any but the slightest application to the realities of life for any but the wealthiest San Antonians. This is how your life should be, the display suggested to bankers from King William Street or ranchers from South Texas—even to shoppers who served in the Mexican government. They all believed Sol Frank and made him rich.

He married a woman from another prominent German Jewish family whose name was also Frank and lived in a large home in a neighborhood called Laurel Heights. In 1897 they had a son, my grandfather, Stanley Frank, who sported curls and starched collars like every stylish boy from the American upper class. At the turn of the century the wealthy Jews of San Antonio were then so few in number that they mingled easily with the rest of prominent San Antonio. Alamo Heights, Olmos Park, and Terrell Hills were never off-limits to Jews in the way of corresponding neighborhoods in Houston or Dallas. Even so, divisions existed, between Jews and gentiles and between Jews and Jews. My great grandfather’s contemporaries were building a world of their own; socially, they kept to themselves, avoiding both the gentile community and the Russian Jews, who had fled the pogroms in the 1880’s. They were part of a drama that was occurring all over the country at the time: To the German Jews, the Russians were poor, loud, and above all, embarrassing. The Russians found the Germans, with their decidedly nonkosher deb balls and harmony clubs, godless, hypocritical, and shallow. “Temple Beth-El were the goyim,” recalled a friend of my parents who is descended from Russian Jews.

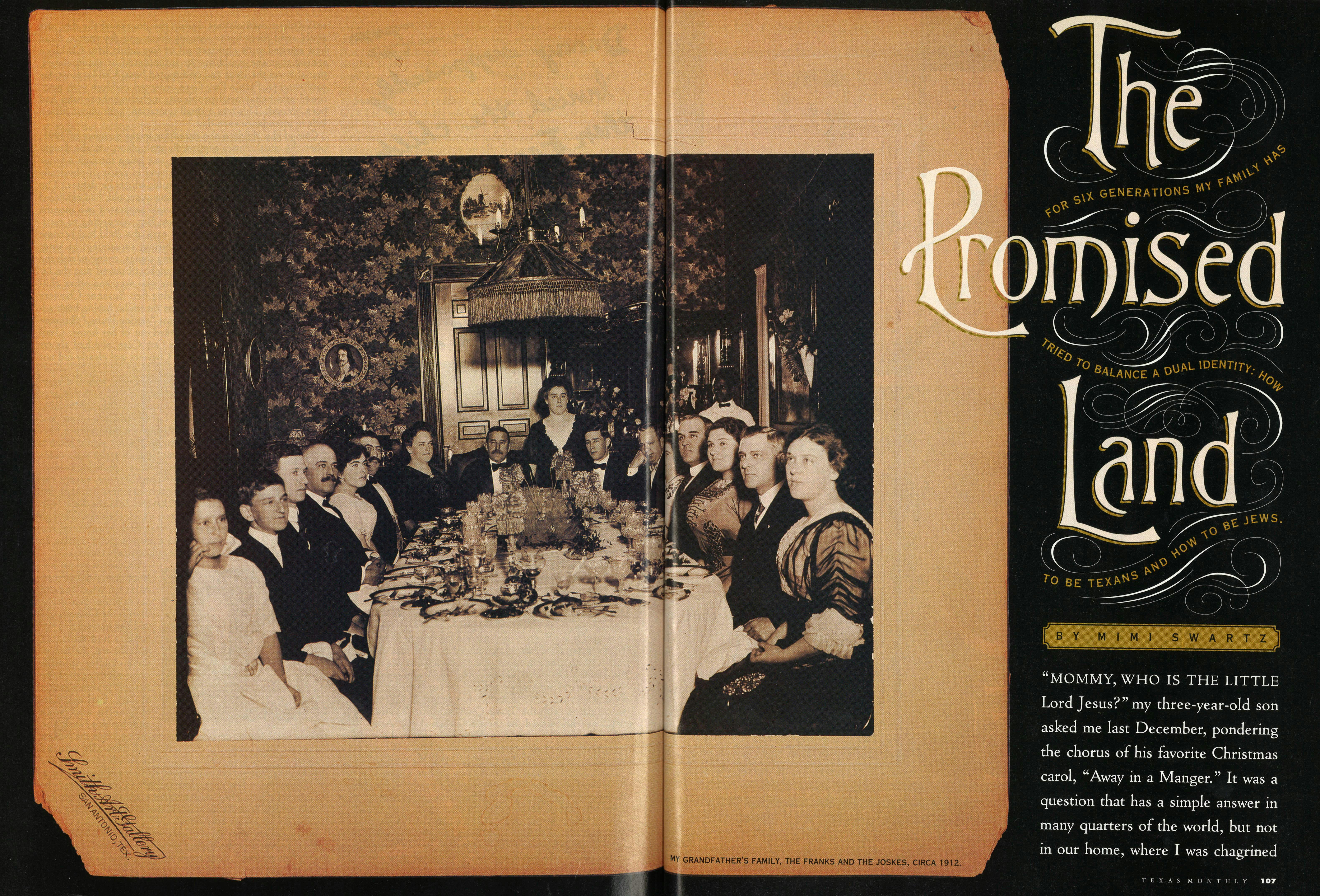

When I imagine the lives of this generation, one family photograph comes to mind. It was taken at Alexander Joske’s home in King William. By then he had inherited his father’s saddle shop and turned it into an immense department store that provided home delivery and had French dressmakers on the second floor. There was no more important merchant in town. He had married my great grandmother’s sister, and now family life—Frank and Joske—revolved around him. My grandfather might have been working for Joske’s then—all the sharp young salesmen trained there—which might explain his attentive posture at the table. Most of the other, older men have the weary look of the driven but accomplished, the women look dreamy-eyed, pampered. I note the brocade on the walls of their dining room, the fine laces of the women’s gowns, the anxious black servant in a corner. I see that in just a scant generation they got what they came for. And that what I am missing—a passionate, lively Judaism—was never what they had in mind.

AFTER MY GRANDMOTHER DIED, we all met with the rabbi at the temple to help him write the funeral service. The family, which had been so united during her illness, seemed at loose ends there. We collected around a glossy table in a large and airless conference room, thickly carpeted, decorated with the imposing portraits of past temple leaders, and we had, essentially, nothing to say. I loved my grandmother deeply—she taught me a hearty skepticism and the little Yiddish I know—but she was difficult to satisfy, particularly in her later years as she became incapacitated by a stroke. Despite her many civic achievements, her life was not easily given to the gentle burnishing people are afforded in death. But I think too that the setting was wrong; we had all—including my grandmother—been gone from the temple too long. On the way out, my mother walked down a brightly lit corridor and found herself in a confirmation picture from the forties. She seemed quietly amazed.

The essence of the Jewish faith is simple and practical: We believe in God but accept responsibility for our actions; we believe that the miracle of life is gift enough and do not expect more in some heavenly afterlife. We do not believe that Jesus Christ was the Son of God; the Old Testament is our book, not the New. From here, however, Judaism, like all religions, becomes more complicated. Once liberated from the ghettos of Europe and the shtetls of Russia, Jews perpetually defined and redefined themselves. Those who still practice the religion have splintered into Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and other sects, depending on their degree of devoutness; many who do not practice still want to claim Judaism as their culture or ethnic group. What has endured longer than any particular belief is a principle of separation. What was once a biblical proposition—that we are God’s chosen—or the result of anti-Semitism has been internalized in contemporary times. As faith fades, every Jew must decide what separates him or her from the gentile world. How far can you go and still call yourself a Jew?

If the Franks were not passionate about practicing their religion, neither were they the kind of Jews who changed their names, married outside the faith, and got on with their lives, as some on the frontier did. They believed in perpetuating the clan, and so they must have been pleased with their good luck when a woman named Hannah Hirshberg, the leader of the temple sisterhood, no less, proposed a match between my grandfather and her niece, Marie Jacobson of Cincinnati. At the close of World War I, something of a courtship circuit had developed in which eligible young women toured the provinces, from Dallas to Memphis to Birmingham, Alabama, in search of prospects. The tour offered something for everyone. The local market of “suitable” Jewish women would have been too small to satisfy San Antonio’s prominent Jewish bachelors, while the world of the Reform Jewish community in a place like Cincinnati would have been too small for someone like my grandmother. Though she came from a family of rabbis and religious scholars, I suspect she believed that religion held you back; she possessed education, ambition, and a startling, shimmering beauty, and she would not have been satisfied to be a traditional Jewish wife whose life revolved around the temple. My grandfather was a shy, kind, but somewhat homely man—a broken nose in childhood had never been set—whose college plans had been thwarted by World War I. Still, he had money and a spotless reputation as a gentleman. The essential Texanness of their bargain sometimes leaves me breathless: My grandmother, a young woman of modest means in Cincinnati, would have to have seen, like so many before her, that the past didn’t matter here, that she could be whoever she wanted. And like so many Texans before him, my grandfather would have found a person who could grace him with the charm and sophistication of the larger world. Judaism wasn’t an issue: My grandparents had many differences, but the place of faith in their lives was not one of them. At nineteen, my grandmother broke swiftly with her past; she married her 32-year-old fiancé not at the temple but at the glamorous St. Anthony Hotel.

They set up a life like that of Sol Frank that revolved around the store. By the 1920’s, Frank Brothers had become a local institution. It now sat on Alamo Plaza across from the Menger Hotel. These days, when I go downtown to the corner of Commerce and Alamo, I am still surprised to see Fuddruckers’ hamburgers instead of Frank Brothers mannequins in what were, once, the windows of the family store. Stores owned by conglomerates are the norm now, but when I was a child, most were the creation of an individual or a family. As a little girl, I understood the sanctity of our store: In the early mornings, before the customers arrived, the blond woods and filtered pink light gave the place an almost sacred feel. Frank Brothers told the world what we as a family and what Jews in general could accomplish. “What did the store mean to my grandfather?” I ask my mother. “Well, it was everything,” she says simply. “Just everything.”

Whether you were Stanley Marcus or a small-town merchant, you claimed and cherished your place as a community leader. Alexander Joske accessorized his newspaper ads with eccentric columns touting the American dream. Frank Brothers heartily supported the rodeo and the horse show and paid for the scoreboard at the minor league field. My grandmother became a volunteer for the symphony society, the museum, and the Red Cross, and as she made her way to the tops of those organizations, she was a walking billboard not just for the store but for the city’s Jews. This world really was open to everyone, or at least it appeared to be.

Work was the way Stanley Frank honored his family, past, present, and future. If my grandfather was not a natural merchant, he knew what every good merchant had to know: He could sense, or could hire the right people who could sense, the color of a sock or the cut of a shoulder that would appeal to his particular community. He knew from year to year what had sold and what had not, he had an acute instinct for the fairest price, and he knew his city: He hired Mexican-American workers not out of any early political correctness but because he needed them for his substantial Mexican clientele; he made sure that Frank Brothers made the uniforms for the Texas Cavaliers, the old-money courtiers for Fiesta week who as a rule excluded Jews, and for the U.S. Army and Air Force, whose bases ringed the town. Frank Brothers offered haircuts for the sons of the aristocracy and made English riding habits for their daughters. The customer, it need hardly be said, was always right.

A misstep could set you apart and ruin not just business but the dream you had inherited in the New World. This was a lesson my grandfather learned as a young man when he helped his uncle Alexander Joske keep the press away from the suspicious drowning of Joske’s son, Harold, who was killed on the Guadalupe River—according to family lore, either by a jealous lover or by a jealous husband. Several years later he handled the details of the elder Joske’s death. Despondent over losing his son, Joske killed himself, but not before calling my grandfather to ask him over for a Sunday drive. Joske wanted my grandfather to find his body. He knew Stanley Frank could be trusted to save the family undue embarrassment.

My grandfather knew that throughout his life he was being held to a harsher standard than non-Jews. There had been a resurgence of anti-Semitism between the wars—the Klan took up its position in Texas in the 1920’s—but even without overt prejudice, the German Jews of San Antonio had kept to their own world, partly by choice and partly in self-defense. My grandparents mixed in their public lives, but they had no close gentile friends before World War II; they remained part of the same small group of German Jews as the generation before them. Even if my grandmother made a name for herself on the society pages, both she and my grandfather knew where the boundary lines were drawn: You didn’t try to join the San Antonio Country Club, because you might be turned down; instead you built your own and made it exclusive to your own crowd. You dissuaded your children from applying to better colleges, hoping they would not ask about the quotas limiting the number of Jews there. In that way, you would not have to be reminded that the promise of this country had not been completely extended to you. In that way, you protected yourself and your children from harm.

You built a life of caution and care—of public perfection. Borders were crossed only in secret: During the Depression, my grandfather, like many retailers, lent money because he had it to lend. If someone welshed on a loan, he usually let it go, for the same reasons he never collected on an unpaid uniform after World War II broke out. He had enough for himself and his family, and, he told my mother, he didn’t want to give anyone the chance to call him a dirty Jew.

ONE OF MY MOTHER’S CONTEMPORARIES grew up far from my grandparents’ home in Olmos Park in a more modest part of town. Her parents were active members of the temple. Her father had a jewelry business, and her mother was a warm, large woman who unlike her stylishly understated daughter favored extravagant displays—hair, makeup, nails, rocks. You couldn’t help but like this woman—in my memory she is always laughing, her lipsticked smile spreading into a scarlet valentine across her face—but she was not a sophisticate, not someone who had learned to turn good taste into another form of self-defense. My mother’s friend remembers her years in temple as an unhappy time, tainted with constant reminders that she could not measure up to the community standard of style and wealth. Struggling to explain this time and place—forties and fifties San Antonio—she falters and then cuts it short. “Let me put it this way,” she begins, in the soft but plaintive way she has of talking. “If you died today and could come back as a Jew, would you?” She stares me down, her normally soft and open face suddenly pinched with old and angry pain. I tell this story to my mother later and expect any answer but the one I get: She nods in complete understanding. A child of the thirties, she remembers feeling isolated not just because of her religion but because of her fear. War refugees were regular guests at dinner, and their stories of the concentration camps shaped her nightmares. My mother was not ashamed to be a Jew, but she grew up believing she could die for being one.

This fear lives on in the epithet of self- hatred that Jews fling at one another. The Hassidim scorn the Orthodox, the Orthodox scorn the Conservatives, the Conservatives scorn the Reform Jews, and so on, in a vicious circle. We are never good enough for each other. Those who are too religious are derided for their avoidance of the real world; those who aren’t religious enough are betrayers of the tribe. That the rest of the world is oblivious to these distinctions—for good and for ill—remains lost on most Jews, though it seems to me the central lesson of my mother’s generation: You couldn’t be at home with your own people, and you certainly couldn’t be at home with non-Jews.

World War II eroded lines between gentiles and Jews, opening up everything from professions to neighborhoods. But the Holocaust proved that, to the outside world, Jews were just Jews, there was no safe place. So my mother was raised with a peculiar mixed message: Be an example in this new world that’s open to you—be the very best—but don’t call attention to yourself. Because the more “Jewish” you were, the more dangerous your life could be.

My mother was then, as she is now, possessed of a delicate beauty that belies her determination; I am always astounded to open her high school yearbooks and see her, poised like some flawless forties mannequin, the social and academic achievements ruthlessly crammed into the space beside her name. My grandparents allowed her to have—and even admired—a best friend who was a pert blue-eyed blond cheerleader, but my grandfather repeatedly warned my mother that such friendships could never last. So it was too that my mother proved herself such an outstanding student that Swarthmore offered her a full scholarship, but my grandparents, fearing anti- Semitism, would not let her go.

Her youth was choreographed as the most complex of ethnic ballets. My mother went to Goucher College in Baltimore because a friend of my grandparents had gone there; it was thought to be safe. Beforehand, thanks to another friend of my grandparents’, my mother was dispatched to Birmingham for Jubilee, a fete for all college-bound Jewish women of a certain class. As with my grandmother a generation before, the purpose was to preserve the clan: The children of that same coterie of German Jews could befriend one another and meet potential mates before ever setting foot on campus. Goucher’s location was itself a crucial part of the plan. Baltimore was a center of clothing manufacturing, hence it was rich in sons of the mercantile class.

Once in school, however, my mother ignored all the nice German Jews and fell for the son of Russian Jews, my father. The appeal would have been obvious: In pictures from that time, he is truly tall, dark, and handsome, his studious black brows barely offsetting an utterly carefree smile. My mother has often told the story of her early encounters with my father’s family—they too were in the clothing business, but in wholesale. They made men’s suits. Like my maternal grandfather, my father’s father had inherited the family business, which he shared with two brothers and a sister. But for that similarity, my parents’ families were polar opposites. My mother went from a home where no one ever raised his voice to one where no one ever dropped it. The Swartzes argued about Zionism, socialism, who really deserved the first violinist’s chair at the philharmonic—undoubtedly they argued about whether my father should marry my mother. They were not at all religious people—my father told me he walked out of the temple after his bar mitzvah, intending never to go back—but they were part of an enormous Jewish community and so they were not afraid. Unrestrained, eccentric, passionate, they decorated their place of business with signs like “Welcome to the Madhouse!” My mother was enchanted.

What my mother would not have been able to see until later was that my father’s family was every bit as rigid as her own. They too had a clan to preserve, and my father was to head it, as well as the family business. They too accepted that the prejudices of others would determine the boundaries of their lives: My paternal grandfather was intensely proud that he sold clothes to state department diplomats, even though that organization would not have hired his own son because he was Jewish.

My mother soon chafed under Swartz family edicts as she had chafed under those of her own parents. When she went looking for a home, she nixed the neighborhoods the family had selected. A real estate agent took her to a restored village just outside of town, where she fell in love with a tiny clapboard house with a stream in back. My mother brought my father to see the place. They were young and happy, and I can see them roaming from room to room, nodding and laughing, able, finally, to visualize a life for themselves in the East. Then the agent asked one question, the one that made my life as a Texan possible. “Are you Christian?” she asked. My father said it was time to leave; my mother said no and asked why the agent posed the question. There was a covenant, the agent explained, that prohibited Jews from living in the neighborhood. “That’s when I made up my mind to move to Texas,” my mother says now.

Though this is a story my mother tells, it always makes me think of my mother’s mother and my father. Both of them saw themselves as Jews, but neither wanted to be isolated in a culture that was purely Jewish. You could say that when my father broke with his past and left with his wife for Texas, he didn’t have much choice, but you could also say that somehow he knew, as my grandmother had known, that the entrance to the larger world lay through the smaller place.

Initially, my father went to work at Frank Brothers—“One thing’s for certain, this clothing trade’s for me,” he none-too-convincingly wrote his new father-in-law. But both my parents began to build a life of their own, away from the old German Jewish community. Unlike my grandparents, they felt no obligation to attend temple regularly, though they retained their membership for a time. They dedicated themselves to the liberal politics of the late fifties and early sixties; with other Jews they joined the coalition of minorities and labor that worked to erode the Anglo establishment that had governed the city for generations. My mother worked for a Spanish-language newspaper and a Hispanic county commissioner. Lines were crossed, boundaries redrawn. For my parents, the life of the spirit was better nurtured in the streets and in the voting booth than in the temple; congressman Henry B. Gonzalez had a Jew as his chief adviser then, one of the more potent signs that the door was open. People whispered that some of the wealthiest Jewish landlords exploited the poorest Hispanics (their gentile business partners, somehow, escaped blame), but in general it was a heady time to be a Jew—you weren’t just included, you were wanted. “It must be wonderful to be Jewish,” a friend of my mother’s exulted at the end of the Six-Day War. “We’ll see what happens next,” my mother said.

My grandfather divined his own particular message from this new world. He was nearing retirement age, and both his son and his son-in-law were leaving the business. The store had become a vestige; there were so many things Jews could do by then that a family business wasn’t needed for the survival of the family. Equally important, the sixties marked the beginning of the age of expansion in retailing. My grandfather’s choice was to borrow more money to expand or to sell the store to someone who could afford to do so. He made the obvious, if painful, decision. Suitors came and went until the day a sharply dressed man from the Hart Schaffner and Marx chain walked onto the floor. My grandfather saw him enter, crisp and confident in a hat and pinstripes. “We just sold the store,” he said to my uncle, and our life on Alamo Plaza began its fade to memory.

ON A FRIDAY NIGHT SEVERAL months ago, my husband and I went to dinner at the home of some new friends. The other guests were a couple from New York. Coincidentally, I had met the woman more than a decade ago, before I had moved back to Houston; she was an old girlfriend of the man I had been seeing. I had liked her then and had hoped to become friends, but distance and circumstance intervened; now we talked easily, comparing careers and children. Just before dinner our host called us to the table and, in honor of the Jews present, took out a pair of candlesticks and politely set them before this woman in preparation for the traditional Sabbath prayer. She started to strike the match to light the candles, but then she turned to me and, in a gesture of friendship, offered me the matchbook. I stared at her hands and, taking a step back from the table, raised my own in protest. She shrugged and turned back to the candles, and as the room warmed with her Hebrew and the soft new light, I felt my face flushing with shame.

It was a child’s response, an all-too-familiar one, that has its impetus in another time and place. I am six or seven, in Sunday school in San Antonio. The teacher, a zaftig woman with black hair styled in a thick French twist, stands before the class. She wears a white shirt and a black skirt; she is all business. “Who is the Father of us all?” she demands of this class of dark-haired eager first-graders. I raise my hand proudly with the answer, but so do all the other children. When the teacher points to me, I hesitate. “Me?” I ask, unsure whom she is calling on. Sharply, she stabs the air toward another student, who wastes no time telling us what we all knew so well—that God is our Father.

I cannot imagine now why the shame of one small misunderstanding would have caused me to do what I did later that day: refuse to return to temple. I had simply had enough. Sunday school was for me a joyless place of intense pressure, of stiff clothes, of Hebrew lessons, of swift punishments, not just for wrong answers but for slow ones. I wonder now if such training wasn’t supposed to serve as preparation for the supposed hostility of the gentile world. For the overwhelming lesson I learned—there before the eyes of God and other Jews—was that I was not yet good enough to call myself a Jew, and I didn’t like it.

My mother’s memory of this episode is vague. She recalls a more protracted departure, some disagreement between my father and the rabbi that reflected the recurring theme of my family’s relationship to the temple for generations: There was some fight over something that could not be remembered, and that was, in essence, the end. My parents continued to give to Jewish causes, to be involved in Jewish events, but they no longer felt the need to continue the charade of a spiritual link.

Whatever happened, I spent much of my life subsequent to that departure trying to return. I was ashamed of my parents’ lack of a religious affiliation and furious with them for making me the only Jew in school on the High Holidays. To save myself embarrassment, I sometimes went to synagogue with my best friend and her family, but then I had to endure their derision when I stumbled over the prayers. Often, I passed the time staring mutely at the Hebrew in the prayer book, furtively checking my seatmate’s copy to be sure I was on the right page. I wanted to belong, to feel connected to the people there, but listening to the rabbi’s sermons, I felt what I now suspect my parents felt: nothing.

Even so, I persisted. Throughout my school years, most of my closest friends were Jewish. Some of them were more religious than I, many were not. No parents or grandparents orchestrated this allegiance to the clan—they didn’t have to. I knew these kids, in the magical way people of shared histories know one another. Our parents had the same books in their houses, they meted out family judgments and expectations in the same way. That most of us were A students we saw as a happy coincidence, not some internalized mandate. We carried our histories lightly.

“Our parents taught us to pass,” an old friend said to me recently, meaning that we did not stand out as stereotypical Jews, meaning in turn that we were safe from anti-Semitism. That goal—if in fact it was a goal—worked only partially. I can count on one hand the number of times I have been subjected to overt anti-Semitism; I can accept my parents’ stories of discrimination only at face value. Even so, I experienced my own subtle reminders that I was an outsider. In seventh grade I had to give a persuasive speech and chose as a topic Why Kids Shouldn’t Wear Surfer Crosses. With a thirteen-year-old’s impassioned diligence, I cut out photographs of Nazi iron crosses and compared them with the fashion of the day; I held up pictures of Auschwitz from books on World War II. I received a substantially lower grade than usual—“Likes to see people squirm” was the teacher’s comment. I had brought something foreign and unpleasant into her classroom, something she clearly did not want to see again.

In that way it was a relief to go East to college, where, just like my mother a generation before, I discovered a world rich in Jews. Feeling some deep connection to my father’s history, I fell in love with a man from Brooklyn and thought I had found my partner for life. He had a shock of coarse curls and almond-shaped eyes. He was quick and funny and, to my public-school intellect, infinitely smarter and more worldly than I. That his parents were Orthodox Jews seemed to me a minor technicality. My boyfriend represented himself as a lapsed Jew, so I thought we were the same. As we set up housekeeping in New York, I did not sense the internal struggle implicit in the stories of his loss of faith—the furtive first encounter with pork-laced Chinese food, his agonizing visits to Auschwitz, his excruciating awareness of the torment his religious rebellion provoked in his aging father. Neither could I understand the fury my lack of knowledge could provoke in him: I was forever offending his parents by telephoning on the Sabbath or by offering culinary compliments that were, at best, inappropriate. (My mother-in-law-to-be’s kosher meal of boiled beef and cabbage would be, for instance, “so much better” than the decidedly nonkosher pepperoni pizza I had had the night before.) I simply thought I had found a way home: He was a real Jew.

One Yom Kippur he took me to an old Conservative temple in Brooklyn Heights, and between prayers, the rabbi paraded the Torah aloft through the aisles. The congregation surged forward to press their prayer books to it, eager to connect themselves not just to God but to one another, and I felt, for the first and only time in my life, some ancient stirring. The voices rose in prayer with conviction; the Hebrew soothed me while the sound of the shofar called me, awakening for a small, sharp second the shock of recognition. This was what I had been seeking: religious practice that was not devoid of feeling. In that instant I believed I could reach back through the generations, marry this man, live in New York, and make what he called “a Jewish home.” Then, as we were walking out, my boyfriend looked at me, stricken. “You’re carrying a purse,” he said, frantic. I looked at him blankly, but I knew what was coming. What rule had I broken now? “You’re not supposed to carry anything into the temple,” he hissed and then moved away from me in disgust. He knew what I did not: the more authentic the experience, the more painful and sacrificial—and impractical.

On his deathbed, my boyfriend’s father made one request: that before we married I take a conversion course so that I could become educated in the Jewish faith. I seethed in shame but stayed on to mark his passing, greeting and serving the mourners who came by for weeks after. Then I went back home to Texas alone, back to being the only kind of Jew I knew how to be.

“WHAT MAKES YOU THINK you’re a Jew?” someone asked me recently. Given the narrative of my life, it is a logical question, but it has always annoyed me. Jews are the only people who ask me this question. The gentile world has rendered its judgment time and time again; it is to my own tribe I am constantly forced to answer. The answer is simply that I am one, even if I am far from the best example. I do not believe that being a Texan and being a Jew are mutually exclusive, though the tribal fidelity so crucial to the latter clashes with the individualism that is almost a religion in itself to most Texans. I do think that to my family, success as a Texan meant success as a Jew: They were concerned with survival, after all, a concern that prosperity could not eradicate. Over time they came to believe that the best way to preserve the family was to blend in, and each generation blended a little more than the one before it. For decades this was not just the Texas way but the American way. Assimilation was not just the norm but the ideal. But I think that what I have felt in my own life is the danger of becoming completely disconnected from my past. There is no temple in my life, no Jewish home, no clan outside of the largest, most diffuse one that I can claim as my own. I have taken from my parents the knowledge that the world is not safe for Jews, that I cannot save my son from hatred, that I can teach him only who he is. But that does not seem like enough anymore.

When my husband and I began to plan our wedding, I visited the Chabad House in Austin at a friend’s recommendation, to see if there might be a way to have a ceremony in which both our religions could be regarded, an effort that I know is anathema to many Jews. (Like some Woody Allen joke, the only rabbis who would marry us were not rabbis we would have. They inevitably had psychology degrees and left messages like “Thank you for sharing” on their answering machines.) The house was just another small frame dwelling close to the Drag, dim and dusty in the fading light of a winter afternoon. But even with his beard and dark heavy clothes, I could see that this rabbi was young, perhaps younger than I, and some instinct quelled an old fear. I explained what I had come for, and he listened intently and then walked me to a bookcase, where he pulled down a few volumes (Your Jewish Wedding, one was called) and put them in my hands. “No, no,” he said, when I turned to go. “First a blessing.” I put the books down, and he closed his hand over mine. It was a wedding prayer, and as we prayed I tried to keep from weeping, partly, I suppose, from prewedding jitters, but mostly from an almost overwhelming loss. It seemed too late for me.

What do I want for my son? That he should know that Jesus is a way that many people get close to God, but those are not the people that his mother is descended from. I would like for him to know the stories and rituals of my people, stories and rituals that were absent from my life. I would like for what I took on faith to be made tangible for him, that he will not feel haunted by the part of himself that refuses to blend. If he walks away after that, at least he will know what he is walking away from.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- San Antonio